Management of Breast Pain

Robert E. Mansel

Breast pain is one of the most common problems for which patients consult primary care physicians, gynecologists, and breast specialists. Patients mistakenly think the symptom is associated with early breast cancer, but data do not support any strong relationship with breast pain. The Women’s Health Initiative Estrogen plus Progestin intervention trials showed no effect on breast cancer risk in women who took estrogens alone, but a mild effect in those taking equine estrogen plus medroxyprogesterone, particularly if baseline breast tenderness was present (hazard ratio [HR] 2.16), but the effect was much less if no baseline breast tenderness was present (1). Once cancer has been ruled out, reassurance alone will resolve the problem in 86% of those with mild and 52% of those with severe mastalgia (2). A survey of screened women in the UK national program revealed that 69% had experienced severe breast pain, although only 3% had sought treatment. Ader et al. in 2001 attempted to establish the prevalence in the community in the United States. In their study, 874 women between 18 and 44 were recruited for interview by random number dialing in Virginia, and 68% reported some cyclical mastalgia, with 22% describing it as moderate or severe (3). Interestingly, patients on the oral contraceptive pill had less trouble, while there was a positive association with smoking, caffeine intake, and perceived stress. A study from the United States (4) showed the impact of breast pain among a population of 1,171 women attending a general obstetrics and gynaecology clinic. Sixty-nine percent suffered regular discomfort and 36% had consulted about their breast pain. A specialist breast clinic in Ghana reported in 2008 that 72% of women attended because of breast pain. Reading of the literature might suggest that the incidence of breast pain is different in many parts of the world, but these differences are mainly cultural in relation to the willingness of women to consult their physicians about breast pain.

The major clinical issue is to exclude cancer and determine the impact on quality of life in patients complaining of breast pain, as this is the primary reason for medication. Only rarely is intervention required, but, after appropriate patient selection, some may derive great benefit from treatment.

ETIOLOGY

Breast swelling is a frequent event in the late luteal phase of the menstrual cycle. Cyclic mastalgia is a more extreme form of this change, and researchers have sought endocrine abnormalities in those with severe breast pain, particularly measuring estradiol, progesterone, and prolactin, but no major abnormalities have been found (5). One hypothesis suggested that inadequate corpus luteal function is an etiologic factor in women with benign breast disease, but this term has been used to include all nonmalignant breast conditions, blurring the distinction between a variety of benign breast conditions. No evidence of progesterone deficiency has been found during the luteal phase in patients with mastalgia. The confusion in the literature between the symptom of breast pain and the large number of variable pathological descriptions of benign breast conditions has resulted in the belief that the condition is a “disease,” rather than physiological responses to menstrual cycles. In the aberrations of normal development and involution (ANDI) classification of benign conditions, mastalgia is regarded as a physiologic disorder arising from hormonal activity with little connection to cancer risk, or true pathologic conditions (6). Another suitable term might be benign breast change as this does not suggest cancer or premalignancy.

No consistent abnormality of estradiol has been reported in women with cyclic mastalgia; both normal levels and elevated levels have been reported during the luteal phase. Baseline levels of prolactin are either normal or marginally elevated, but increased prolactin release was found after domperidone stimulation in severe cyclic mastalgia, possibly representing a stress response to prolonged pain.

Ecochard et al. measured a range of personal and endocrine variables in 30 women with mastalgia and 70 control subjects (7). Cases were more likely to report foot swelling or abdominal bloating (43% vs. 19%). Women with mastalgia had higher mean luteal levels of luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH).

No histologic differences have been detected in biopsies from women with and without mastalgia. Immunohistochemical examination of biopsies from 29 women with mastalgia and 29 control subjects revealed no differences in expression of interleukin-6, interleukin-1, and tumor necrosis factor.

CLASSIFICATION

Preece et al. (8) proposed a classification with six subgroups based on a prospective study of 232 patients with breast pain: cyclic mastalgia, duct ectasia, Tietze’s syndrome, trauma, sclerosing adenosis, and cancer. This was subsequently simplified into two groups with noncyclic pain: true noncyclic breast pain and those with other causes of chest wall pain (9). Although an accurate diagnosis can be achieved on the basis of history and examination, patients with breast pain can be more simply assigned to one of three groups: cyclic breast pain (around 70%), noncyclic breast pain (20%), or extramammary pain (10%).

Khan and Apkarian (10) studied the differences between cyclic and noncyclic pain using standardized pain questionnaires, including the McGill Pain instrument in 271 women, and found that the level of pain described by the subjects was equivalent to chronic cancer pain, and just less than the pain of rheumatoid arthritis. They noted that women with cyclic pain tended to refer to heaviness and tenderness as found in the Preece study, whereas women with noncyclic pain related the severity to the area of breast involved.

EVALUATION

Important aspects of history-taking include the type of pain, relationship to menses, duration, location, and any other medical problems. The impact of the pain on the everyday activities of the patient, particularly sleep and work, should be established to assess the need for medication.

After inspection, the first aspect of the breast examination should be very gentle palpation of the breasts once the patient has indicated the site(s) of the pain. Having excluded discrete masses, a more probing evaluation should be performed, focusing on the site(s) of pain. After turning the patient half on her side so that the breast tissue falls away from the chest wall, it may be possible to identify that the pain is arising from the underlying rib or costal cartilage. The pain can be reproduced by placing a fingertip on the affected rib and demonstrating to the patient its source.

Nodularity can be associated with mastalgia, but the extent is unrelated to pain severity; in younger women, the finding is so common that it should be considered within the spectrum of normality. If it is apparent that the pain, whether cyclic or noncyclic, is mammary in origin, the decision to treat is based on the subjective assessment of severity, together with the duration of symptoms. This assessment may be facilitated by a daily pain chart that assesses the timing and severity (semiquantitative scale) of the pain. Generally, there should be a history of pain of at least 4 months before hormonal therapy is indicated.

ROLE OF RADIOLOGY

The average age of women entered into trials of treatment for mastalgia is 32 years: In this age group, mammography is not a standard adjunct to clinical evaluation. In the absence of a discrete lump, ultrasonography is also unlikely to give useful information, but any breast lump present requires triple assessment. No specific mammogram findings are associated with breast pain.

Ultrasonography in 212 asymptomatic women and 212 with mastalgia showed the mean maximal duct dilatation was 1.8 mm in normal women compared with 2.34 mm in the 136 with cyclic pain and 3.89 mm in the 76 with noncyclic pain. Dilated ducts were found in all quadrants, but mostly in the retroareolar area, and dilatation did not alter during the menstrual cycle. A highly significant association was found between the extent of ductal dilatation and pain severity.

The meaning of these findings are unclear as no relationship was shown in the cyclic pain patients with the considerable temporal symptoms in this group, but the noncyclic group could be explained by the periductal inflammation often seen in this group.

MONDOR’S DISEASE

Mondor’s disease is a rare cause of breast pain, with diagnostic clinical features of local pain associated with a tender, palpable subcutaneous cord or linear skin dimpling. The cause is superficial thrombophlebitis of the lateral thoracic vein or a tributary. The condition resolves spontaneously. Mondor’s disease can cause serious alarm because some patients assume that the skin tethering is secondary to an underlying carcinoma, so they are greatly relieved when informed of the benign nature of the condition.

In a series of 63 cases of Mondor’s disease, no underlying pathologic process was found in 31 cases. Of the remaining 32, local trauma or surgical intervention was responsible in 15 (47%), an inflammatory process in 6 (19%), and carcinoma in 8 (25%). In view of this, mammography should be performed in women with Mondor’s disease who are aged 35 years or older to exclude an impalpable breast cancer.

PSYCHOSOCIAL ASPECTS

Several studies have confirmed that patients with severe mastalgia have psychological morbidity that may be the result rather than the cause of their breast pain. Preece et al. (11) used the Middlesex Hospital Questionnaire to compare patients with mastalgia, psychiatric patients, and minor surgical cases. No significant differences were found between the patients with breast pain and the surgical cases, and both scored significantly lower than psychiatric cases. Only the scores of patients who failed treatment approached those of psychiatric patients. In a small study of 25 women with severe mastalgia, using the Composite International Diagnostic Interview, 45 diagnoses were made in 21 patients (84%): anxiety (n = 17), panic disorder (n = 5), somatization disorder (n = 7), and major depression (n = 16).

A study using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) reported high levels of both anxiety and depression in 20 women with severe mastalgia. At Guy’s Hospital, HADS was also used to evaluate 54 patients with mastalgia (12). The 33 women with severe pain manifested levels of anxiety and depression comparable with those in women with breast cancer before surgery. Those who responded to treatment had a significant improvement in psychosocial function, but the nonresponders continued to have high levels of distress. Fox et al. (13) conducted a prospective trial in 45 women with mastalgia who kept pain diaries for 12 weeks, with half randomized to listen daily to a relaxation tape during weeks

5 to 8. Abnormal or borderline HADS scores were found at entry in 54%, and a complete or substantial reduction in pain score was measured in 25% of the control subjects and 61% of those randomized to relaxation therapy (p < .005).

5 to 8. Abnormal or borderline HADS scores were found at entry in 54%, and a complete or substantial reduction in pain score was measured in 25% of the control subjects and 61% of those randomized to relaxation therapy (p < .005).

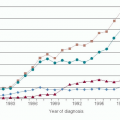

MASTALGIA AND BREAST CANCER RISK

Because of the lack of precision in classification of benign breast conditions in older studies, it was difficult to determine whether breast pain led to an increased risk of subsequent breast cancer. Foote and Stewart wrote in 1945, “Any point of view that one chooses to take concerning the relation of so-called cystic mastitis to mammary cancer can be abundantly supported from the literature.”

Webber and Boyd carried out a critical analysis of the 36 published papers that were available in English before 1984. They set 16 standards, including a description of the study population, a definition of benign disease, follow-up, and a description of the risk analysis. Of the 22 studies reporting an increase in risk, all met more of the standards than the 11 suggesting no increase in risk and the 3 drawing no conclusions.

Since then, a few studies have specifically examined the relation between cyclic mastalgia and breast cancer risk. A French case-control study among premenopausal women— 210 younger than 45 years of age with breast cancer, and 210 neighborhood control subjects—matched on year of birth, education level, and age at first full-term pregnancy gave an unadjusted relative risk (RR) for cancer in cyclic mastalgia of 2.66, and after adjustment for family history, prior benign breast disease, and age at menarche, the RR was still significantly elevated at 2.12.

Goodwin et al. (14) recruited 192 women with premenopausal node-negative breast cancer and 192 age-matched premenopausal control subjects. Significant risk variables for breast cancer in the model were marital status, family history, number of years of smoking, prior breast biopsy (before cancer diagnosis), and mean cyclic change in breast tenderness. The odds ratio of cancer for cyclic mastalgia was 1.35, rising to 3.32 in those with severe pain.

Another indication of a possible link between mastalgia and cancer is the relationship between Wolfe grade of mammograms and breast pain. Deschamps et al. (15) determined the Wolfe grades of 1,394 women in the Canadian National Breast Screening Study. All completed a questionnaire, with mastalgia reported by 46%. The extent of dysplasia on mammograms was categorized as Dy2 (25% to 49%), Dy3 (50% to 74%), and Dy4 (≥75%). The odds ratio for a Dy3/4 rating was 1.0 for those who never had breast swelling and mastalgia, whereas it was 2.7 in those reporting both symptoms.

These epidemiologic studies have the problems of recall biases and unknown extent of histologic atypia in the patients who have not had biopsies. In most studies assessing risk using established algorithms, the presence of breast pain is not used as an independent variable in the calculations, unlike prior breast biopsy. That women attend a physician for breast pain, itself results in a higher rate of breast biopsy as noted in the study by Ader et al. (3).

TREATMENT TRIALS

Multiple treatments have been used in women with “benign breast disease,” some of whom had nothing more than nodularity without tenderness. Patients with diffusely nodular breasts that are painless require nothing other than exclusion of significant pathology and can be discharged if no other indications for follow-up exist.

Treatment trials for breast pain should have well-documented breast pain classified into cyclic or not, measured with a visual analog scale (VAS) or other rating scales, and ideally using each patient as her own control. Pain should have been present for a minimum of 6 months. Assessment of nodularity should be assessed separately from pain, and has been validated in a study of two experienced blinded physicians assessing 784 women using a VAS giving a highly significant interobserver correlation with a kappa value of 0.865 (16). The overall quality of most published studies has been poor with low numbers of patients recruited, and varying methodologies used. Trials should be of double-blinded, placebo-controlled, randomized design and include a minimum of 20 patients in each arm. Some trials have met these criteria and defined effective drugs or interventions; results are summarized in Table 6-1.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree