Malignant Lymphoma of the Genitourinary Tract

Jeremy S. Abramson

M. Dror Michaelson

INTRODUCTION

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) represents the fifth most common cancer in the United States, with approximately 66,000 new cases diagnosed annually (1). NHLs are a heterogeneous group of diseases, with over four dozen discrete subtypes presently recognized by the World Health Organization (2). Autopsy series have demonstrated a high rate of secondary involvement of the urogenital tract by NHL, estimated at approximately 20% to 30%, particularly in high-grade lymphomas (3,4,5). Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is the most common subtype of NHL and may involve both nodal and extranodal locations, with up to 40% of cases isolated to an extranodal site at presentation (6). Though DLBCL is the most common NHL to involve the genitourinary (GU) tract, others include Burkitt lymphoma, lymphoblastic lymphoma, anaplastic large cell lymphoma, extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma, extranodal marginal zone (mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue [MALT]) lymphoma, and others.

Any part of the male or female GU tract may be involved by NHL, but the testis is the most common primary site of GU lymphomas, where it carries distinct biology and natural history from NHLs in other nodal and extranodal locations. Understanding of the unique clinical and biological features of NHL in the GU tract is critical to the management of these uncommon, but highly treatable neoplasms.

TESTICULAR NON-HODGKIN LYMPHOMA

Epidemiology

Lymphoma involving the testis was initially described in 1877 (7) and is now recognized as a unique clinicopathologic variant of NHL. Primary testicular lymphoma is a rare entity, representing <1% of all newly diagnosed lymphoma, and approximately 5% of all testicular neoplasms, but incidence appears to be increasing (8,9). The dominant neoplasms of the testis, seminomatous and nonseminomatous germ cell tumors, occur in younger patients compared to testicular lymphomas that present later in life, making lymphoma the most common testicular neoplasm in patients over the age of 60 (8,10,11). Predisposing factors may include undescended testicles, trauma, and HIV infection, though the vast majority of cases are sporadic (12,13,14).

Pathology

Nearly all cases of lymphoma involving the testis are NHL, although rare cases of Hodgkin lymphoma have been reported. More than 80% of all cases of lymphoma of the testis are classified as DLBCL (10,15). Very high-grade B-cell lymphomas, including Burkitt lymphoma and lymphoblastic lymphoma/acute lymphoblastic leukemia, may also occur in the testis, though rarely as an isolated presentation. Low-grade histologies have been infrequently reported and include follicular or extranodal marginal zone lymphomas (15,16,17). Extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type, is an uncommon lymphoma associated with the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) and, though most commonly located in the upper aerodigestive tract, may present or relapse in other extranodal sites, including the testis (2,18,19).

Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis

Primary testicular lymphoma most commonly presents as painless, unilateral testicular enlargement. Bilateral involvement may also occur and has been variably reported as affecting 6% to 35% of cases at diagnosis (9,10). Pain is unusual and suggests an alternate diagnosis. The median age of affected patients is 68 to 71 years with only one quarter of cases occurring under the age of 60 (9,10). Most cases of testicular lymphoma are diagnosed at limited stage (Ann Arbor stage I or II), most commonly isolated to the testis (stage IE), but approximately 20% will be advanced at presentation (11). Stage II disease frequently involves retroperitoneal lymph nodes, and advanced-stage testicular lymphomas commonly involve other extranodal sites, including the central nervous system (CNS), bone marrow, Waldeyer’s ring, adrenal glands, kidneys, skin, soft tissue, bone, lung, liver, or gastrointestinal tract (11). Systemic “B” symptoms of fevers, drenching night sweats, and weight loss are uncommon in testicular lymphomas, present in <10% of patients at diagnosis, and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) is elevated in only one quarter of patients (11). Alphafetoprotein and beta-human chorionic gonadotropin are not elevated in testicular lymphomas.

Sonographic appearance is generally of a focal infiltrative hypoechoic mass without a defined capsule, or of a diffusely enlarged testis with homogeneously decreased echogenicity (20,21,22,23). Extension may be observed into the epididymis or spermatic cord, though rarely into the tunica albuginea, and the overall testicular architecture may remain preserved. The diagnostic procedure of choice is radical inguinal orchiectomy (24). Trans-scrotal needle aspirates may obtain insufficient tissue for diagnosis of indeterminate lesions (25), and concern for tumor seeding of a sanctuary site from chemotherapy limits this approach.

Staging

Staging evaluation for testicular lymphoma should include thorough physical examination including careful examination of Waldeyer’s ring, skin, and the CNS. Routine radiographic staging should include computed tomography scans of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis, preferably in combination with 2-(18)F-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose/positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) scan, as high-grade lymphomas of the testis are uniformly brightly FDG-avid. Ultrasound of the contralateral testis should be included given the propensity for bilateral presentation, and a bone marrow aspiration and biopsy is typically performed. Laboratory studies should include complete blood count, chemistries including renal and hepatic

function, uric acid, phosphorous, and a serum LDH level. The presence of any symptoms referable to the CNS at diagnosis should prompt evaluation with a brain MRI and diagnostic lumbar puncture given the increased risk of CNS dissemination. Because of the association of testicular lymphoma with underlying HIV infection, an HIV serology should be checked at baseline. In anticipation of chemotherapy, Hepatitis B serologies should be checked to evaluate the risk of hepatitis B reactivation with combination chemotherapy. Since the treatment program for nearly all patients will include an anthracycline, a baseline echocardiogram is also recommended.

function, uric acid, phosphorous, and a serum LDH level. The presence of any symptoms referable to the CNS at diagnosis should prompt evaluation with a brain MRI and diagnostic lumbar puncture given the increased risk of CNS dissemination. Because of the association of testicular lymphoma with underlying HIV infection, an HIV serology should be checked at baseline. In anticipation of chemotherapy, Hepatitis B serologies should be checked to evaluate the risk of hepatitis B reactivation with combination chemotherapy. Since the treatment program for nearly all patients will include an anthracycline, a baseline echocardiogram is also recommended.

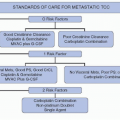

Prognosis and Treatment

Prognosis of primary testicular lymphomas has historically been reported to be poor, with 50% to 80% of patients experiencing relapse of their disease and less than half of patients alive 5 years after diagnosis (11,26,27). These series, however, included a heterogeneous assortment of therapies ranging from orchiectomy alone to intensive chemotherapy with radiation, with improved outcomes observed for patients treated with combination chemotherapy and prophylactic therapy directed at the CNS and contralateral testis.

Testicular lymphoma should be considered a systemic disease at presentation, even in stage IE lymphomas that are confined to the testis. Early series of patients treated with orchiectomy alone for testis-limited disease demonstrated a surprisingly poor prognosis with up to 80% of patients suffering distant lymphoma relapse within 2 years of orchiectomy and a median survival of only 1 year (8,11,26). Unlike nonlymphoid testicular tumors, the addition of radiotherapy to retroperitoneal lymph nodes after orchiectomy has likewise yielded disappointing results, with approximately 70% of patients relapsing, typically outside the radiation field, further demonstrating that testicular lymphoma must be considered a systemic disease regardless of the initial clinical presentation (11,28,29). Disease-free and overall survival improved with the addition of anthracycline-containing chemotherapy, but historical series continue to demonstrate an inferior prognosis than would be predicted for their nodal DLBCL counterparts (11,27,29,30). This appears in part due to a unique timing and pattern of relapse in testicular lymphoma, with recurrence risk continuing a decade out from treatment without plateau, and propensity for recurrence within the contralateral testis, brain parenchyma, and other extranodal sites. Specific CNS and contralateral testis-directed therapy with intrathecal chemotherapy and prophylactic scrotal irradiation, respectively, have appeared to offer benefit in retrospective analysis (11), though outcomes vary widely across published series.

In the M.D. Anderson series of 22 patients with testicular DLBCL, all received doxorubicin-based therapy, and five also received radiotherapy (31). Complete remission was attained in 73% of patients. At 153 months, failure-free survival was only 16% for all patients. All patients who failed to respond to primary therapy, and 50% of patients who relapsed from complete remission, had CNS and/or contralateral testicular involvement.

The Mayo Clinic reviewed their experience in 62 patients whose median age was 68 (26). Following orchiectomy, 37% received combination chemotherapy and 16% received combined modality therapy plus radiotherapy. At 2.7 years of follow-up, 80% of patients had relapsed, with 60% of patients dead from disease. Contrary to a number of previous reports, in which nearly all relapses occurred within 2 years, late recurrences were common in this series, with no plateau of the relapse-free survival curve. Thirteen patients relapsed in the CNS, which was the sole site of relapse in eight patients. Eleven of 13 patients had parenchymal brain disease without leptomeningeal involvement.

In another series, Lagrange described 84 cases with a median age of 67, 75% of whom were categorized as DLBCL (32). Following surgery, 40% of patients received chemotherapy and 33% received combined modality therapy. Complete response was attained in 73% of patients who were stratified according to stage as follows: 100% stage I, 68% stage II, and 33% stages III-IV disease. Relapse occurred in 38%, nine of whom had CNS disease. The median overall survival was 32 months for the entire group, with 52 months for stage I disease; 32 months for stage II; and 12 months for stages III-IV. CNS prophylaxis was not employed.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree