Summary of Key Points

- •

Maintenance therapy offers the possibility of continued active treatment to delay disease progression and symptom deterioration and, more importantly, improved overall survival of patients with advanced nonsmall cell lung cancer (NSCLC) already treated with induction chemotherapy.

- •

The target population for maintenance are patients who achieved objective response or disease stabilization with induction chemotherapy with minimal cumulative toxicity.

- •

Meta-analyses and patients’ preference support the use of maintenance in advanced NSCLC.

- •

Maintenance chemotherapy doesn’t impair quality of life nor generate an additional cost compared with the benefits achieved.

- •

Excluding targeted agents with known driver mutations, no predictive biomarkers are available to select better candidates for maintenance therapy with chemotherapy.

- •

In this setting new treatment opportunities with immunotherapy and other agents represent a research priority.

The quest to control NSCLC has been long and remains frustrating, but since the 2000s, substantial advances have been made in therapeutic options for patients with this disease. The most striking advances have been in treatments linked to the identification of molecular changes acting as so-called drivers of malignancy for many patients, but optimization of the delivery of chemotherapy, particularly with maintenance therapy, has also led to improved survival for patients.

The concept of maintenance therapy was initially rejected after several studies published in the early 2000s demonstrated that continuation of a platinum-based doublet beyond four cycles did not result in a significant survival advantage but did cause progressive toxicity. Around the same time, studies demonstrated the efficacy of second-line chemotherapy, most notably with docetaxel. The overall interpretation of these results led to the standard treatment paradigm of treatment with a platinum-based doublet for four cycles (six for patients who had response) followed by a so-called treatment holiday until the time of progression, at which point standard second-line chemotherapy was offered. The widespread belief was that patients benefited from a break from chemotherapy and that close surveillance would provide the opportunity for patients to receive beneficial future treatments.

This approach began to be questioned, however, with the development of new agents. For example, some new chemotherapy drugs, such as pemetrexed, could be given on a continuous basis with a lower risk of long-term toxicities such as neuropathy, which had limited the long-term use of other agents, such as the taxanes. In addition, the era of targeted agents began, and almost all of these agents (such as bevacizumab, erlotinib, and gefitinib) are administered continuously until progression.

The maintenance approach is currently defined as continuation or switch maintenance treatment. With continuation maintenance, one or two of the agents administered as part of a first-line combination regimen are continued beyond the four to six cycles. This concept is not completely new because it was extensively investigated in several trials starting in the 1980s, but it was only in 2006, with the licensing of bevacizumab, that an approved drug was available in a continuous maintenance setting. More recently, strongly positive data with pemetrexed given as continuation maintenance therapy after four cycles of a platinum-based doublet further contributed to a change in the treatment paradigm. Less compelling data support the use of gemcitabine as continuous maintenance therapy.

The concept of switch maintenance is more recent and is based on switching to an alternative agent (i.e., one that was not part of the first-line regimen) after completion of four to six cycles of doublet chemotherapy in the absence of disease progression. Definitive data support the use of pemetrexed and erlotinib, and less robust data are available for docetaxel. It could be argued that such an approach may be simply considered early initiation of second-line treatment. Although the agents investigated in this setting, namely pemetrexed, erlotinib, and docetaxel, are indeed all approved agents for standard second-line therapy, their use for patients who had an objective response or disease stabilization after completion of first-line chemotherapy is biologically different from their use after disease progression. The term early second-line treatment is therefore inaccurate and should not be used.

The results of the Sequential Tarceva in Unresectable NSCLC (SATURN) and JMEN trials were the true impetus for maintenance therapy, which led to guidelines in support of maintenance therapy, issued in 2011, and increased awareness about the benefits of this approach. Clinical investigations in this area have helped demonstrate that second-line chemotherapy is subsequently given to about two-thirds of patients who have a treatment holiday after disease stabilization with four to six cycles of chemotherapy. Maintenance therapy, either as continuation or switch, leads to improved survival for patients with NSCLC.

Historical Maintenance Trials

In 1989, a study to evaluate the effect of prolonging chemotherapy for patients with stable disease beyond two or three cycles of a four-drug regimen (methotrexate, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, and lomustine) found no benefit for a longer duration. The study was small, with 74 patients randomly assigned to maintenance chemotherapy or to discontinuation of chemotherapy, and the results showed a nonsignificant trend toward longer overall survival of nearly 4 months for maintenance chemotherapy, but cast doubt on the use of prolonged first-line chemotherapy or maintenance therapy. Despite this uncertainty, patients and physicians seemed to favor continued therapy, as evidenced by difficulty in recruiting to a randomized trial of six courses of mitomycin-C, vinblastine, and cisplatin compared with observation after three cycles of the same regimen. The authors noted that most patients who declined to enroll in the study said they refused because they preferred to continue treatment. However, despite this challenge, the trial was completed and it showed no improvement in survival for prolonged chemotherapy and demonstrated an increase in fatigue and other types of toxicities, further supporting the idea that less is better when considering the continuation of combination cytotoxic regimens. At that time, the number of treatment cycles varied, as did the regimens used for first-line therapy.

Socinski et al. published the results of a practice-changing trial in 2002. The backbone regimen for this trial was carboplatin and paclitaxel, based on the findings of multiple phase III studies performed in the United States and Europe that had demonstrated the tolerability and efficacy of this regimen. All patients received four cycles of carboplatin (area under the curve [AUC] of 6) and paclitaxel (200 mg/m 2 ) on a 21-day regimen, with disease assessment after every two cycles. Patients in one arm of the trial had a break from treatment after four cycles, with assessments for progression done every 6 weeks, and patients in the other arm received chemotherapy every 3 weeks until disease progression or until the decision was made to end treatment. It was planned that all patients were to receive second-line therapy with weekly paclitaxel (80 mg/m 2 ) given at the time of progression. A total of 230 patients were enrolled, predominantly between 1998 and 1999. Response rates were 22% and 24%, respectively, in the two arms, with no additional responses after four cycles for patients who had received continued chemotherapy. The median survival times were 6.6 and 8.5 months, respectively, but the difference was not significant ( p = 0.63). Of note, 45% of patients received second-line chemotherapy, and more patients received continued chemotherapy than were given a treatment holiday. Toxicities, particularly neuropathy, were higher among patients who received continued chemotherapy, but there was no clear difference in quality of life between the two treatment arms. The conclusion drawn from this trial was that treatment beyond four cycles of a platinum-based doublet did not lead to improved survival and could lead to increased toxicity. Thus, the standard practice shifted toward this approach, with an additional two cycles offered to patients who had a response, such that four to six cycles of a platinum-based doublet, followed by a treatment holiday, was the standard approach. Two subsequent studies addressed the question of four versus six cycles of first-line chemotherapy, and both failed to show a clear benefit with the additional two cycles, thus supporting four cycles of first-line doublet therapy as the standard of care.

Another contemporary phase III study compared three cycles with six cycles of carboplatin (equivalent to AUC of 5) given on day 1 and vinorelbine (25 mg/m 2 ) on days 1 and 8 every 3 weeks. A total of 297 patients were enrolled, and the median survival was 28 weeks for three cycles and 32 weeks for six cycles (hazard ratio [HR], 1.04; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.82–1.31; p = 0.75), casting further doubt on the additional benefit of prolonged cycles of first-line chemotherapy.

All of these studies evaluated continuation of the initial regimen beyond four to six cycles compared with a true maintenance approach assessing prolongation of chemotherapy only in patients benefiting from platinum-based chemotherapy. An early maintenance study comparing a continuation and a switch approach enrolled 493 patients in 2000–2004 to receive three cycles of a triplet regimen (gemcitabine, ifosfamide, and cisplatin) on an every-3-week schedule. After three cycles, the 281 patients who did not have disease progression were randomly assigned to receive continued chemotherapy until disease progression or intolerability, or to receive switch maintenance therapy with paclitaxel (225 mg/m 2 ) every 3 weeks, also continued until disease progression or intolerability. The progression-free survival was similar in both arms (4.4 vs. 4.0 months; p = 0.56). Although numerically the median overall survival favored continued chemotherapy (11.9 vs. 9.7 months), the difference was not significant ( p = 0.17). The 1-year survival rate was 49% for continued chemotherapy and 42% for switch therapy. Putting this trial into context with other maintenance studies is challenging, as patients in both arms continued with treatment until disease progressed, the randomization occurred after only three cycles of a platinum-based combination, and a substantial number of patients in each arm received the opposite regimen at the time of disease progression (69 of the 140 patients in the continued chemotherapy arm subsequently received paclitaxel).

One of the first true maintenance studies evaluated switch maintenance therapy with vinorelbine after four cycles of mitomycin, ifosfamide, and cisplatin. The study registered 573 patients with advanced stage NSCLC treated either with chemoradiation therapy for stage III disease or chemotherapy for stage IV disease, but only 181 were randomly assigned to the treatment arms of maintenance therapy with vinorelbine or no maintenance therapy. Of the 91 patients in the maintenance therapy arm, 7 died as a result of toxicity. No survival advantage was noted, which dampened enthusiasm for this approach.

A randomized phase II trial demonstrated more robust activity with continuation maintenance therapy with paclitaxel. The trial included 401 patients who were randomly assigned to one of three treatment groups: weekly paclitaxel with every-4-week carboplatin or weekly paclitaxel with weekly carboplatin according to two different schedules. Patients who did not have disease progression at week 16 were further randomly assigned to maintenance therapy with weekly paclitaxel (70 mg/m 2 ) for 3 of 4 weeks or to observation (65 patients in each group). The every-4-week carboplatin regimen was superior in terms of response, and the maintenance therapy resulted in a 9-week longer time to progression, a 15-week improvement in median survival, and improvements in 1- and 2-year survival rates. This study was conducted to determine the optimal weekly regimen of paclitaxel and carboplatin, and the efficacy of maintenance therapy was not a key question. However, these results led to adoption of maintenance therapy in the subsequent phase III trial, in which 444 patients were randomly assigned to weekly paclitaxel (100 mg/m 2 ) for 3 of 4 weeks plus carboplatin (AUC of 6) on day 1 of an every-4-week cycle or to standard every-3-week paclitaxel (225 mg/m 2 ) on day 1 with carboplatin (AUC of 6). Patients in both treatment groups subsequently received maintenance therapy with paclitaxel (70 mg/m 2 ) for 3 of 4 weeks until disease progressed. Although the toxicity profiles differed, the efficacy outcomes did not. Because maintenance therapy with paclitaxel was given to patients in both groups, its contribution is not clear.

Positive results with a continuation maintenance approach were found in a trial evaluating gemcitabine. Of the 352 patients enrolled who received cisplatin (80 mg/m 2 ) on day 1 and gemcitabine (1250 mg/m 2 ) on days 1 and 8 every 3 weeks, 206 patients had no disease progression and were eligible for random assignment to continuation with gemcitabine or to no further treatment (2:1 randomization). Maintenance therapy with gemcitabine was associated with a significantly improved time to progression and a trend in favor of overall survival that did not reach statistical significance (median, 13.0 vs. 11.0 months; p = 0.195). Because of the lack of a significant improvement in overall survival, the results did not have a major impact on clinical practice.

Although study findings suggested a benefit with maintenance therapy, particularly continuation maintenance with paclitaxel or gemcitabine, additional positive results were not reported until 2008. The tolerability of docetaxel, gemcitabine, and, more recently, pemetrexed, led to continued exploration of the concept of maintenance therapy.

Modern Maintenance Trials

Switch Maintenance With Chemotherapy ( Table 46.1 )

Fidias et al. pioneered the modern use of the switch maintenance approach in a clinical trial in which 309 (54.6%) of 566 patients with nonprogressive disease after four cycles of first-line gemcitabine and carboplatin were randomly assigned to second-line treatment with docetaxel (maximum of six cycles) either immediately or at the time of disease progression. The median progression-free survival was longer for patients treated with immediate docetaxel than for patients treated with delayed docetaxel (5.7 vs. 2.7 months; HR, 0.71; p = 0.0001). The difference in median overall survival between the two treatment approaches did not reach significance (12.3 vs. 9.7 months; HR, 0.84; p = 0.0853) in this undersized trial. Overall survival was the primary end point of the trial, which lessened the impact of the other results. Approximately 37% of the patients assigned to receive delayed docetaxel never received it because of substantial symptomatic deterioration, death, or the investigator’s decision. A subanalysis restricted to patients who did receive docetaxel in both arms showed that overall survival was identical in both arms (12.5 months), suggesting that the trend toward improved outcomes was associated with more patients in the immediate group receiving docetaxel. The toxicity profiles were similar for the two treatment approaches, and no differences in quality-of-life factors were found.

| Induction Treatment a | Maintenance Treatment | Poststudy Treatment (%) | Progression-Free Survival | Overall Survival | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author/Trial | Regimen | Regimen | Median Age (Y) | PS 2 (%) | SCC Histology (%) | Never-Smokers (%) | Women (%) | Study Drug | Any | HR (95% CI) | Median (Mo) | p | HR (95% CI) | Median (Mo) | p | Toxicity | Quality of Life |

| Fidias et al. | Carboplatin AUC 5 on day 1; gemcitabine 1000 mg/m 2 on days 1 & 8, every 3 wk × 4 | Docetaxel 75 mg/m 2 every 3 wk × 6 ( n = 153) Observation ( n = 156) | 65.4 65.5 | 5.9 10.3 | 16.3 18.8 | NR NR | 37.9 37.8 | NR 63 | NR NR | 0.71 (0.55–0.92) | 5.7 2.7 | 0.0001 | 0.84 (0.65–1.08) | 12.3 9.7 | 0.0853 | Neutropenia: 27.6%; febrile neutropenia: 3.5%; fatigue: 9.7% Neutropenia: 28.6%; febrile neutropenia: 2%; fatigue: 4.1% | No differences (LCSS) |

| JMEN | Platinum-based doublet (without pemetrexed) every 3 wk × 4 | Pemetrexed 500 mg/m 2 every 3 wk + best supportive care ( n = 441) Placebo + best supportive care ( n = 226) | 60.6 60.4 | 0 0 | 26 30 | 26 28 | 27 27 | <1 18 | 51 67 | 0.50 (0.42–0.61) | 4.3 2.6 | 0.0001 | 0.79 (0.65–0.95) | 13.4 10.6 | 0.012 | Total: 16% Fatigue: 5%; anemia: 3%; infection: 2% Total: 4% Fatigue: 1%; anemia: 1%; infection: 0% | No overall differences; better control of pain & hemoptysis |

a In the trial by Fidias et al. 566 patients received induction treatment, and 309 (54.6%) were randomly assigned to maintenance therapy; the number of patients in JMEN who received induction treatment was not recorded.

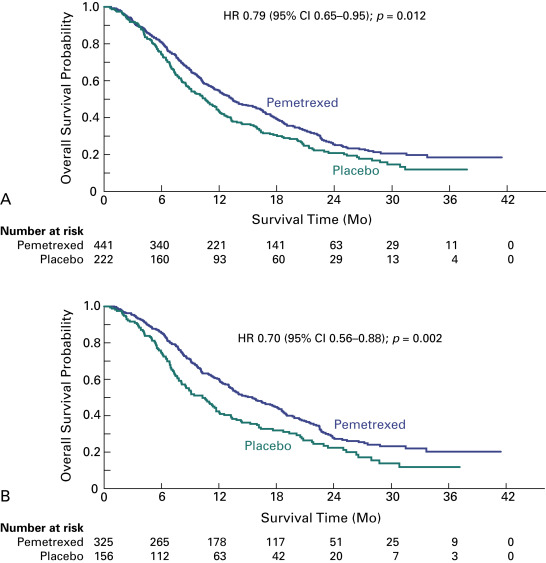

The JMEN trial evaluated pemetrexed as single-agent switch maintenance therapy. The trial design did not incorporate mandatory poststudy therapy, randomization was 2:1, and progression-free survival was the primary end point, which drew criticisms compared with the trial by Fidias et al., in which overall survival was the primary end point. However, the advantages of the JMEN trial were that its statistical assumptions were more realistic and the sample size allowed for more robust comparisons. In this trial, 663 patients with stage IIIB or IV disease who did not have disease progression during four cycles of platinum-based chemotherapy (without pemetrexed) were randomly assigned to receive best supportive care with or without pemetrexed until disease progression. Maintenance therapy with pemetrexed significantly improved the median progression-free survival (4.3 vs. 2.6 months; HR, 0.50; 95% CI, 0.42–0.61; p < 0.0001) and overall survival (13.4 vs. 10.6 months; HR, 0.79; 95% CI, 0.65–0.95; p = 0.012) ( Fig. 46.1A ). Of note, relatively fewer patients in the pemetrexed group received systemic postdiscontinuation therapy (51% vs. 67%; p = 0.0001), and 19% of patients in the control group received salvage treatment with pemetrexed. A prespecified analysis showed a significant interaction between treatment and histology, consistent with the findings in similar prior trials in different NSCLC settings. For patients who had tumors with nonsquamous cell histology, pemetrexed was associated with a greater benefit in terms of both progression-free survival (4.4 vs. 1.8 months; HR, 0.47; 95% CI, 0.37–0.60; p < 0.00001) and overall survival (median, 15.5 vs. 10.3 months; HR, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.56–0.88; p = 0.002), compared with patients who had tumors with squamous cell histology ( Fig. 46.1B ). In a subgroup analysis, the overall survival advantage with pemetrexed was greater for patients with stable disease at the end of induction chemotherapy (HR, 0.61) than for patients who had a partial or complete response (HR, 0.81). Treatment discontinuations due to drug-related toxic effects were more frequent with pemetrexed than with placebo (5% vs. 1%), as were drug-related grade 3 or 4 adverse events (16% vs. 4%; p < 0.0001), particularly fatigue (5% vs. 1%; p = 0.001) and neutropenia (3% vs. 0%, p = 0.006). No pemetrexed-related deaths occurred. Quality-of-life evaluations showed no global differences but a significant delay in worsening of pain and hemoptysis. As a result of this trial, both the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Association (EMA) approved pemetrexed as switch maintenance therapy for metastatic NSCLC, specifically for patients with nonsquamous cell tumors in whom disease has not progressed after first-line platinum-based chemotherapy.

Continuation Maintenance With Chemotherapy ( Table 46.2 )

Since the 2006 publication of a phase III trial of continuation maintenance with gemcitabine, this approach has been evaluated in two additional studies. In the first of these studies, patients with stable or responsive disease after carboplatin plus gemcitabine were assigned to either gemcitabine with best supportive care or best supportive care alone (control). The study closed after 6 years because of slow accrual, with 225 patients randomly assigned instead of the planned 332. Of note, most patients had a performance status of 2 at study entry (64%) and of 2 or 3 at the time of randomization (57%). Maintenance treatment with gemcitabine was generally well tolerated, however there was a higher incidence of grade 3 or 4 toxicity, namely, anemia, neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, or fatigue. The treatment arms did not differ in terms of progression-free survival (HR, 1.09; 95% CI, 0.89–1.45) or overall survival (HR, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.72–1.30). The trial outcomes appeared to have been influenced by the unfitness of the study population; for example, the rate of poststudy treatment was 16% in the gemcitabine arm and 17% in the control arm. Indeed, patients with a poor performance status had a significantly worse outcome than patients with a performance status of 1 (HR, 1.50; 95% CI, 1.10–2.03; p < 0.009). Based on these and similar results, there is agreement that maintenance treatment should not be recommended to patients with a poor performance status. The implications of these results on the adoption of continuation maintenance with gemcitabine for other patients are less clear, as it is likely the negative findings were based more on the general fitness of the enrolled patients than on a lack of effectiveness of gemcitabine per se.

| Induction Treatment | Maintenance Treatment | Poststudy Treatment (%) | Progression-Free Survival | Overall Survival | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author/Trial | Regimen | No. of Patients Randomized (%) | Regimen | Median Age (Y) | PS 2 (%) | SCC Histology (%) | Never-Smokers (%) | Women (%) | Study Drug | Any | HR (95% CI) | Median (Mo) | p | HR (95% CI) | Median (Mo) | p | Toxicity | Quality of Life |

| Belani et al. | Carboplatin AUC 5 on day 1; gemcitabine 1000 mg/m 2 on days 1 & 8, every 3 wk × 4 ( n = 519) | 255 (49.1) | Gemcitabine 1000 mg/m 2 on days 1 & 8, every 3 wk + best supportive care ( n = 128) Best supportive care alone ( n = 127) | 67.2 67.5 | 64 76 | NR NR | NR NR | 40 33 | 2 3 | 16 17 | 1.04 (0.81–1.45) | 3.9 3.8 | 0.58 | 0.97 (0.72–1.30) | 9.3 8.0 | 0.84 | Neutropenia: 15%; anemia: 9%; fatigue: 5% Neutropenia: 2%; anemia: 5%; fatigue: 2% | NR |

| IFCT | Cisplatin 80 mg/m 2 on day 1; gemcitabine 1250 mg/m 2 on days 1 & 8, every 3 wk × 4 ( n = 834) | 464 (55.6) | Gemcitabine 1250 mg/m 2 on days 1 & 8, every 3 wk ( n = 154) Observation ( n = 155) | 57.9 59.8 | 2.6 1.2 | 22.1 19.4 | 11 7.7 | 26.6 27.1 | 0 0 | 77.2 90.9 | 0.56 (0.44–0.72) | 3.8 1.9 | 0·001 | 0.89 (0.69–1.15) | 12.1 10.8 | 0.3867 | Neutropenia: 20.8%; anemia: 2.6%; fatigue: 1.9% Neutropenia: 0.6%; anemia: 0.6%; fatigue: 0% | No differences |

| Zhang et al. | Cisplatin 75 mg/m 2 on day 1; docetaxel 60 or 75 mg/m 2 on day 1, every 3 wk × 4 ( n = 378) | 184 (48.7) | Docetaxel 60 mg/m 2 day 1, every 3 wk × 6 + best supportive care ( n = 123) Best supportive care alone ( n = 61) | 5.4 2.8 | 0·002 | NR | ||||||||||||

| PARAMOUNT | Cisplatin 75 mg/m 2 on day 1 + pemetrexed 500 mg/m 2 on day 1, every 3 wk × 4 ( n = 939) | 539 (57.4) | Pemetrexed 500 mg/m 2 every 3 wk + best supportive care ( n = 359) Placebo + best supportive care ( n = 180) | 60 62 | 0 0 | 0 0 | 223 19 | 44 38 | 2 4 | 64 72 | 0.62 (0.40–0.79) | 4.1 2.8 | 0·0001 | 0.78 (0·64–0.96) | 13.9 11.0 | 0.0195 | Neutropenia: 5.8%; anemia: 6.4%; fatigue 4.7% Neutropenia: 0%; anemia: 0.6%; fatigue: 1.1% | No differences (EQ-5D) |

| AVAPERL | Cisplatin 75 mg/m 2 & pemetrexed 500 mg/m 2 + bevacizumab 7.5 mg/kg on day 1, every 3 wk × 4 ( n = 376) | 253 (67.3) | Pemetrexed 500 mg/m 2 + bevacizumab 7.5 mg/kg on day 1, every 3 wk ( n = 128) Bevacizumab 7.5 mg/kg on day 1, every 3 wk ( n = 125) | 60 60 | 1.9 5.8 | 0 0 | 24.8 26.1 | 42.4 43.3 | NR | 69.6 70.8 | 0.48 (0.35–0.66) | 7.4 3.7 | 0·001 | 0.87 (0·63–1.21) | 17.1 13.2 | 0.29 | Any: 37.6% Neutropenia: 5.6%; anemia: 3.2%; fatigue: 2.4% Any: 21.7% Neutropenia: 0%; anemia: 0%; fatigue: 1.7%; | No differences |

| PointBreak | Carboplatin AUC 6 + pemetrexed 500 mg/m 2 + bevacizumab 15 mg/kg on day 1, every 3 wk × 4 Carboplatin AUC 6 + paclitaxel 200 mg/m 2 + bevacizumab 155 mg/kg on day 1, every 3 wk × 4 | 590 (62.8) | Pemetrexed 500 mg/m 2 + bevacizumab 15 mg/kg on day 1, every 3 wk ( n = 292) Bevacizumab 15 mg/kg on day 1, every 3 wk ( n = 298) | 63.8 64.3 | 0 0 | 0 0 | 13.4 11.8 | 49.3 46.6 | 13.4 39.9 | 57.2 64.8 | NR | 8.6 6.9 | NR | NR | 17.7 15.7 | 0.84 | Neutropenia: 14%; anemia: 11%; fatigue: 9.6% Neuropathy: 0%; hypertension: 3.1% Neutropenia: 11.4%; anemia: 0.3%; fatigue: 1.7% Neuropathy: 4.7%; hypertension: 6.0% | No differences except less neurotoxicity was reported in the pemetrexed arm (FACT-G, FACT-L FACT & GOG-Ntx) |

| PRONOUNCE | Carboplatin AUC 6 + pemetrexed 500 mg/m 2 on day 1, every 3 wk ( n = 182) Carboplatin AUC 6 + paclitaxel 200 mg/m 2 + bevacizumab 15 mg/kg on day 1 every 3 wk × 4 ( n = 179) | 193 (52.4) | Pemetrexed 500 mg/m 2 on day 1 every 3 wk ( n = 98) Bevacizumab 15 mg/kg on day 1 every 3 wk ( n = 95) | 65.8 65.4 | 0 0 | 0 0 | 32.2 3.9 | 7.7 34.1 | 47.3 52.5 | 77.2 90.9 | 1.06 (0.84–1.35) | 4.4 5.5 | 0–610 | 1.07 (0.83-1.36) | 10.5 11.7 | 0.615 | Neutropenia: 25%; anemia: 19%; thrombopenia: 24%; fatigue: 6.4%; vomiting: 1.8% Neutropenia:49%; anemia: 5%; thrombopenia: 10%; fatigue 5.4%; vomiting: 5.48% | No differences |

In the second of the studies, the IFCT-GFPC 0502 trial, patients were randomly assigned to observation or one of two different drugs for maintenance therapy, gemcitabine or erlotinib, if they did not have disease progression after four courses of induction therapy with cisplatin plus gemcitabine. Progression-free survival was the primary end point, and no comparison between the two maintenance arms was planned. The study design imposed the same second-line treatment (pemetrexed) in all three arms to avoid bias in the survival analysis as a result of an imbalance in subsequent treatments. Independently assessed progression-free survival was almost 2 months longer in the gemcitabine arm than in the observation arm (HR, 0.55; 95% CI, 0.54–0.88; p = 0.003), and the benefit was consistent across all clinical subgroups, including different histologies. Preliminary survival analysis did not show any meaningful differences among the study arms, but patients who received second-line pemetrexed or who had a performance status of 0 appeared to derive greater benefit. Exploratory analysis showed that the magnitude of response to induction chemotherapy may affect the overall survival benefit of maintenance therapy with gemcitabine. Among patients with an objective response to induction chemotherapy, the median overall survival was 15.2 months with gemcitabine compared with 10.8 months with observation (HR, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.51–1.04). Maintenance with gemcitabine was well tolerated, with grade 3 or 4 treatment-related adverse events (mostly neutropenia and thrombocytopenia) reported more commonly in the gemcitabine arm (27%) than in the observation arm (2%).

The TFINE study evaluated the role of docetaxel in the continuation maintenance setting. In this study, 378 patients were initially randomly assigned (1:1) to receive cisplatin (75 mg/m 2 ) plus docetaxel (75 mg/m 2 or 60 mg/m 2 ) for four cycles. Patients with stable disease after first-line treatment were subsequently randomly assigned (1:2) to best supportive care or maintenance therapy with docetaxel (60 mg/m 2 ) for up to six cycles. The two docetaxel doses yielded similar response rates as induction treatment, but the higher dose was associated with higher rates of diarrhea and neutropenia. Continuation maintenance therapy with docetaxel significantly prolonged progression-free survival at a magnitude similar to that in the switch setting (median, 5.4 vs. 2.8 months; p = 0.002).

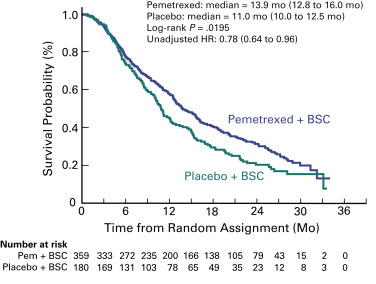

The PARAMOUNT trial was designed to determine if maintenance therapy with pemetrexed would improve efficacy compared with placebo after four courses of cisplatin and pemetrexed in patients with advanced nonsquamous cell NSCLC. Of the 939 patients enrolled, 57% were randomly assigned (2:1) after the induction phase to continuation maintenance therapy with pemetrexed plus best supportive care or placebo plus best supportive care. The primary objective of this study, progression-free survival, was improved in the maintenance therapy arm compared with the placebo arm (median, 4.1 vs. 2.8 months, HR, 0.62; p = 0.0001). An independent review of progression-free survival (88% of patients) confirmed the investigator-assessed results. The mature survival analysis confirmed the superiority of maintenance therapy with pemetrexed (median overall survival, 13.9 vs. 11.0 months; HR, 0.78; p = 0.0195; Fig. 46.2 ). Pemetrexed improved survival consistently, including response to induction therapy (HR, 0.81) and stable disease (HR, 0.76). Use of postdiscontinuation therapy was similar: 64% and 72% in the maintenance therapy arm and placebo arm, respectively. Pemetrexed remained tolerable for the vast majority of patients, even in the long-term; however, the rates of anemia, fatigue, and neutropenia were higher in the maintenance therapy arm than in the placebo arm. No significant differences in health status were found during maintenance therapy between the arms, as assessed with the EQ-5D questionnaire. The EMA approved pemetrexed as continuation maintenance therapy based on the findings of this study.

Another trial (AVAPERL) analyzed the contribution of pemetrexed maintenance in combination with bevacizumab in patients exposed to both drugs in a cisplatin-based triplet as induction therapy. The trial included 376 patients with nonsquamous cell NSCLC, 253 of whom were randomly assigned to maintenance therapy. Compared with bevacizumab alone, pemetrexed plus bevacizumab significantly prolonged progression-free survival from the time of induction therapy (median, 10.2 vs. 6.6 months; HR, 0.50; 95% CI, 0.37–0.69; p < 0.001) and from the time of randomization (median, 7.4 vs. 3.7 months; HR, 0.48; 95% CI, 0.35–0.66; p < 0.001). This benefit was confirmed in all major subgroups analyzed, including patients with stable disease or response after induction therapy. An updated evaluation on overall survival, a secondary end point, showed a nonsignificant 4-month advantage in favor of the combined maintenance treatment (median, 13.1 vs. 17.2 months; HR, 0.87; p = 0.29). More severe toxicity occurred in the pemetrexed plus bevacizumab arm, including grade 3–5 hematologic events (10.4% vs. 0%) and nonhematologic events (31.2% vs. 21.7%). A smaller trial assessed the same experimental arm with the combination of pemetrexed and bevacizumab as maintenance therapy after a carboplatin-pemetrexed-bevacizumab induction regimen in comparison with the same induction regimen followed by pemetrexed alone; the primary end point was the progression-free survival rate at 1 year. The study was clearly underpowered and 1-year progression-free survival did not significantly differ between the two arms. However, there was a trend favoring the combined maintenance arm with a median progression-free survival measured from enrollment of 11.5 months compared with 7.3 months in the pemetrexed maintenance arm (HR, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.44–1.19; p = 0.198). Two other trials have provided further information on the role of continuation maintenance therapy with pemetrexed, one with bevacizumab and one without. The PointBreak trial randomly assigned 939 patients with advanced nonsquamous cell NSCLC to receive induction treatment with pemetrexed, carboplatin, and bevacizumab followed by maintenance therapy with pemetrexed and bevacizumab or to induction treatment with paclitaxel, carboplatin, and bevacizumab followed by bevacizumab. In contrast to expectations, this trial showed superimposable survival curves for both treatment arms (HR, 1.00; p = 0.949), with a modest benefit in progression-free survival (HR, 0.83; 95% CI, 0.71–0.96; p = 0.012) favoring the pemetrexed and bevacizumab arm. It must be noted, however, that the induction phase of the study is important to the final overall analysis, as when the analysis is restricted to the 590 patients who were followed up after maintenance therapy (292 who received pemetrexed and bevacizumab and 298 who received bevacizumab alone), the separation of the progression-free survival curve (median, 8.6 vs. 6.9 months) as well as the overall survival curve (median, 15.7 vs. 17.7 months) is more apparent, although not of the magnitude seen in the AVAPERL study.

The toxicity was as expected based on the known profiles of the agents, including more anemia and fatigue for patients who received pemetrexed as part of induction therapy, and more neuropathy and hypertension for patients who received paclitaxel. Patient-reported changes in quality of life did not differ according to treatment, with the exception of neurotoxicity and alopecia, which were less frequently associated with pemetrexed.

The PRONOUNCE study also compared two combined induction plus maintenance strategies in advanced nonsquamous NSCLC. The primary end point, progression-free survival without grade 4 toxicity, has controversial clinical relevance. Patients were assigned to receive four courses of pemetrexed and carboplatin followed by pemetrexed (182 patients) or paclitaxel, carboplatin, and bevacizumab followed by bevacizumab (179 patients). There were no differences in progression-free survival (HR, 1.06; p = 0.610) or overall survival (HR, 1.07; p = 0.616). Therefore, this undersized trial did not demonstrate a difference in efficacy between the two approaches, but equivalence cannot be claimed, as the trial did not robustly rule out differences of moderate or small magnitude. There were no unexpected findings in terms of safety profile for either regimen.

Another trial, ERACLE ( NCT00948675 ), compared cisplatin and pemetrexed with pemetrexed maintenance to carboplatin, paclitaxel, and bevacizumab with bevacizumab maintenance. This trial is similar to PRONOUNCE, with three exceptions: the platinum agent used (cisplatin vs. carboplatin), the number of induction chemotherapy cycles (6 vs. 4), and the primary end point (differences in quality of life between the two arms vs. progression-free survival without grade 4 toxicity). This underpowered randomized study only showed a nonsignificant trend favoring the pemetrexed arm for EuroQoL 5 Dimensions-Index.

We await a large phase III trial of continuation versus switch maintenance therapy. Two small phase II trials have addressed this debate, but neither was large enough to provide conclusive findings. In one of these studies, patients were randomly assigned to four cycles of either carboplatin and paclitaxel or carboplatin and gemcitabine; patients in both arms who had no disease progression subsequently received gemcitabine (1000 mg/m 2 ) on days 1 and 8 every 3 weeks. The progression-free survival was 4.6 months in the paclitaxel (switch) arm and 3.5 months in the gemcitabine (continuation) arm, and there was no difference in the median overall survival (approximately 15 months in both arms; HR, 0.79; p = 0.60). In the other study, conducted in Japan, patients who had disease control after four cycles of induction chemotherapy with carboplatin and pemetrexed were randomly assigned to receive either continuation therapy with pemetrexed or switch therapy with docetaxel. The study enrolled 85 patients, 51 of whom subsequently received maintenance therapy. The median progression-free survival from the time of randomization was 4.1 months for continuation therapy with pemetrexed compared with 8.2 months for switch therapy with docetaxel (HR, 0.56; 95% CI, 0.28–1.08; p = 0.084). The overall survival from the time of randomization was 20.6 months for continuation therapy compared with 19.9 months for switch therapy (HR, 0.79; 95% CI, 0.3–2.00; p = 0.622). Although no firm conclusions can be drawn from such a small study, the results are intriguing and do not make a clear argument in favor of switch versus continuation maintenance. It is interesting to note that more than 30% of patients in the switch therapy arm received pemetrexed as second-line therapy and 45% of patients in the continuation therapy arm subsequently received docetaxel as second-line therapy. Larger trials of this nature are needed to help resolve this question.

Maintenance With Noncytotoxic Agents

Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Inhibitors ( Table 46.3 )

Maintenance therapy with cytotoxic drugs evolved in parallel with the development of targeted therapy agents with mechanisms of action and toxicity profiles supporting long-term use. The use of these agents tended to continue until disease progression rather than be stopped after a predefined number of cycles. Many targeted therapy agents are taken daily by mouth.

| Induction Treatment | Maintenance Treatment | Poststudy Treatment (%) | Progression-Free Survival | Overall Survival | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author/Trial | Regimen | No. of Patients Randomized (%) | Regimen | Median Age (Y) | PS 2 (%) | SCC Histology (%) | Never-Smokers (%) | Women (%) | Study Drug | Any | HR (95% CI) | Median | p | HR | Median (Mo) | p | Toxicity | Quality of Life |

| SATURN | Platinum-based chemotherapy × 4 cycles ( n = 1949) | 889 (45.6) | Erlotinib 150 mg daily ( n = 458) Placebo ( n = 451) | 60 60 | 0 0 | 38 43 | 18 17 | 27 25 | 11 21 | 71 72 | 0.71 (0.62–0.82) | 12.3 wk 11.1 wk | <0.0001 | 0.81 (0.70–0.95) | 12.0 11.0 | 0.0088 | Any 3+: 12% Rash: 60% (9% 3+); diarrhea: 18% Any 3+: 1% Rash: 8% (0% 3+); diarrhea: 3% | No differences (FACT-L) |

| IFCT | Cisplatin 80 mg/m 2 on day 1; gemcitabine 1250 mg/m 2 on days 1 & 8 every 3 wk × 4 ( n = 834) | 464 (55.6%) | Erlotinib 150 mg daily ( n = 155) Observation ( n = 155) | 56.4 59.8 | 5.2 2.6 | 17.4 19.4 | 11 7.7 | 27.1 27.1 | 5.8 0 | 79.9 90.9 | 0.69 (0.54–0.88) | 2.9 1.9 | 0.003 | 0.87 (0.68-1.13) | 11.4 10.8 | 0.3043 | Rash: 63% (9% 3/4); diarrhea: 20% Rash (3/4): 0%; diarrhea: <1% | No differences |

| ATLAS | Platinum-based chemotherapy + bevacizumab × 4 ( n = 1160) | 768 (66%) | Bevacizumab & erlotinib (150 mg) daily ( n = 370) Bevacizumab & placebo ( n = 373) | 64 64 | 0 0 | 3 1.6 | 16.5 17.7 | 47.8 47.7 | 39.7 39.7 | 50.3 55.5 | 0.722 (0.59–0.88) | 4.76 3.75 | 0.0012 | 0.90 (0.74–1.09) | 15.9 13.9 | 0.2686 | Rash (3/4): 10%; diarrhea (3/4): 9% Rash (3/4): <1%; diarrhea (3/4): <1% | NR |

| WJTOG 0203 | Carboplatin/paclitaxel OR 1 of 4 cisplatin doublets × 3 ( n = 604) | Gefitinib 250 mg daily after 3 cycles of chemotherapy ( n = 302, with 298 treated) Gefitinib 250 mg daily after up to 6 cycles of chemotherapy ( n = 301, with 297 treated) | 62 63 | 0 0 | 21 32 | 30 32 | 36 35 | 58 0 | 75 55 (gefitinib) | 0.68 (0.57–0.80) | 4.6 4.3 | <0.001 | 0.86 (0.72–1.03) | 13.7 12.9 | 0.11 | Transaminitis (3/4) 11% Transaminitis (3/4) 4% | No differences (LCS v 4) | |

| INFORM | Platinum doublet (NP) × 4 ( n = 296) | Gefitinib 250 mg ( n = 148) Placebo ( n = 148) | 55 55 | 2 3 | 18 20 | 53 55 | 44 38 | 3 a 8 a | 51 67 | 0.42 (0.33–0.55) | 4.8 2.6 | <0.0001 | 0.84 (0.62–1.14) | 18.7 16.9 | 0.26 | Any rash: 50%; diarrhea: 25%; 3 toxicity-related deaths Rash: 9%; diarrhea: 9% | FACT-L–time to worsening slowed on gefitinib arm (odds ratio, 3.41; 95% CI, 1.65–7.06; p = 0.0009) | |

| EORTC 08021 | Platinum doublet (NP) × 4 ( n = 173) | Gefitinib 250 mg ( n = 86) Placebo ( n = 87) | 61 62 | 7 5 | 17 22 | 21 23 | 22 24 | 15 b 40 b | 40 c 67 c | 0.61 (0.45–0.83) | 4.1 2.9 | 0.002 | 0.81 (0.59–1.12) | 10.9 9.4 | 0.204 | Transaminitis (3/4): 10.6%; fatigue: 4.7%; rash (3): 1.2% Transaminitis (3/4): 1.2%; fatigue: 1.2%; rash (3): 0% | No differences | |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree