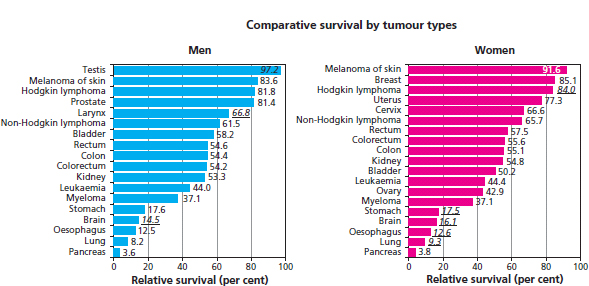

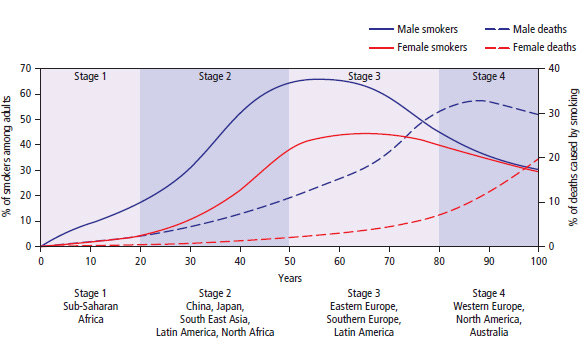

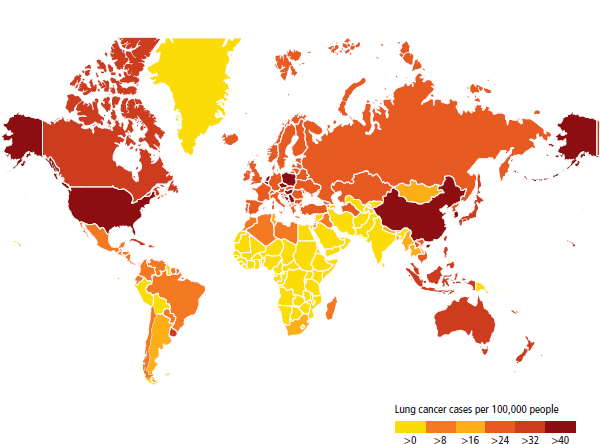

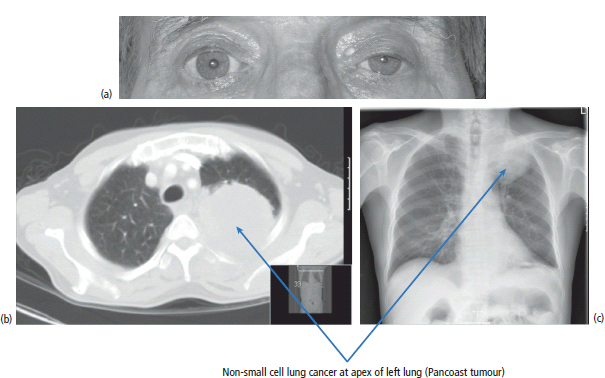

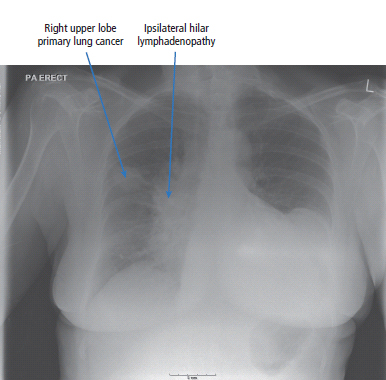

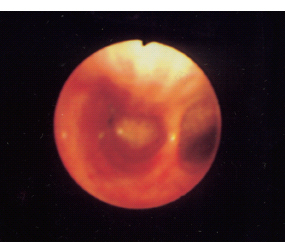

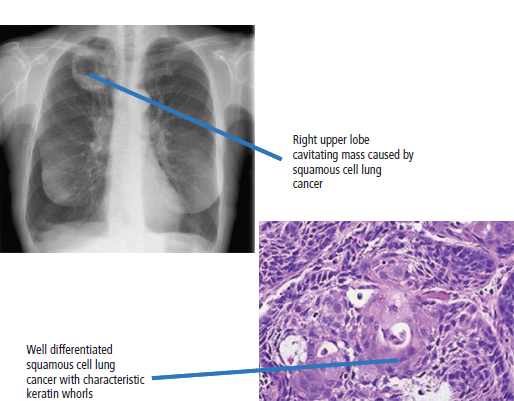

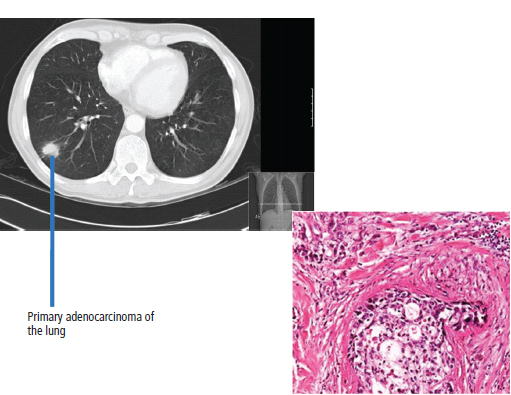

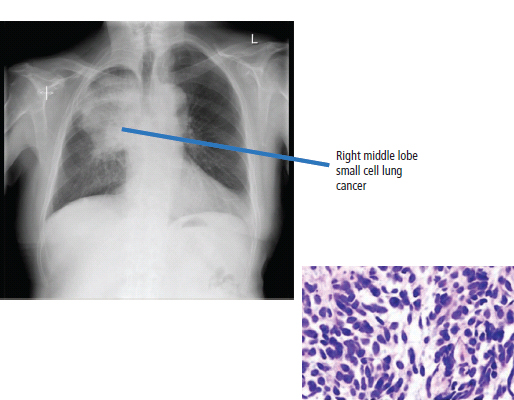

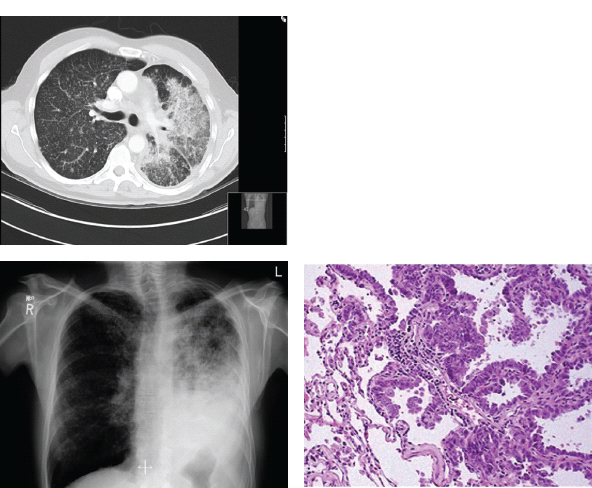

26 In a celebrated television documentary Death in the West, produced in 1976 by Thames Television, the vice president of the tobacco company Philip Morris attempted to dismiss established links between tobacco and cancer. During the interview he said: “Too much of anything can kill you. Too much apple sauce can kill you”. And: “If there were something harmful in tobacco smoke, we could remove it”. Despite numerous court cases, the tobacco industry continues to target the young and encourage smoking. It took until 1999 for the Royal Family to withdraw its royal warrant from the tobacco multinational Gallaher, which entitled them to display “By Appointment” on packs of Benson & Hedges cigarettes. This was despite the death of the last three kings from tobacco-related disease, including King George VI, who died of lung cancer. Lung cancer is the second most common tumour of both men and women in the United Kingdom (Figure 26.1). The overall prospects for survival are poor: fewer than 10% of patients survive 5 years from diagnosis (Table 26.1). In the United Kingdom, there were 43,463 new diagnoses and 35,184 deaths from lung cancer in 2011. The most important cause of lung cancer is smoking, and the incidence of lung cancer is directly related to the number of cigarettes smoked (see Box 2.5). It is estimated that smoking is responsible for 86% of lung cancers and that smoking causes a total of 102,000 deaths a year in the United Kingdom. Smoking contributes to the risk of many different cancers including: At present there are 10 million smokers in the United Kingdom having declined from a peak in the mid 1970s. In 1974, there were 10 cigarettes smoked each day per adult male and 5 cigarettes smoked per day per adult woman in the United Kingdom (Figure 26.2). One in two regular smokers will eventually be killed by the habit and half of them will die before the age of 70. The link between smoking and lung cancer was established 50 years ago and since then 6.5 million people have died in the United Kingdom because of tobacco-related disease (Figure 26.3). Figure 26.1 Lung cancer – the second most common cancer and the second worst survival. The Department of Health has adopted six strategies to try and reduce the deaths from smoking: Examples of these strategies include the introduction of smoke-free legislation in 2007 and public education through graphic television anti-smoking advertisements. Raising duty on cigarette sales also reduces consumption; a 10% price rise reduces consumption by 4%. However, this is undermined by increasing levels of tobacco smuggling, which is estimated to account for 16% of the current UK cigarette market. Tobacco advertising promotion and sponsorship is banned in the United Kingdom and plain packaging of cigarettes should be introduced in 2015, unless the government makes another U-turn on this policy. Table 26.1 UK registrations for lung cancer 2010 Public policy on smoking has been led by a complex cost–revenue balance. It is said that if all smoking ceased, the loss of revenue from tobacco taxation coupled to increases in pension payments because of reduced mortality would bankrupt UK Plc. Others argue that the revenue generated by smoking pays for the cost of care to the NHS of smoking-related illness. These are not great arguments. In 1999, an NHS stop smoking service was established. In addition to encouragement advice and avoidance strategies, most clients are provided with pharmacological support: usually nicotine replacement therapy, bupropion or varenicline. Nicotine replacement therapy is meant to be used for a short length of time with gradual tapering off of the dose. It is available as transdermal patches, gum, lozenges, sprays and inhalers. Nicotine replacement therapy increases the chances of stopping smoking by 50% compared to placebo but the vast majority of over-the-counter users will relapse within 6 months. Figure 26.2 The evolving global epidemic of smoking. Source: Edwards R. The problem of tobacco smoking. BMJ, 2004;328(7433):217. Reproduced with permission of BMJ Publishing Group Ltd. Figure 26.3 The evolving global epidemic of lung cancer. The antidepressant bupropion (Zyban) reduces nicotine craving and is generally used for 12 weeks with advice to stop smoking 10 days into the course. The most important side effect is epileptic seizures and both headaches and insomnia are common. Bupropion is about as effective as nicotine replacement therapy but fewer people will return to smoking after completing the course. Varenicline (Champix) is a partial nicotinic acetylcholine receptor agonist that reduces both craving and enjoyment of tobacco. It causes nausea and less frequently neuropsychiatric disturbances. It is more likely to result in smoking cessation, with a 1-year complete abstention rate of 23%. Despite all these efforts and advances, the rate of decline in smoking in the United Kingdom is only 0.4% per year. Smoking causes cancer because tobacco smoke contains at least 19 pyrolytic carcinogens. These include polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH) such as benzopyrenes that are metabolized in the liver into potent epoxides that bind irreversibly to the bases of DNA resulting in mutations. Similarly, acrolein in cigarette smoke alkylates guanine bases but this does not require prior metabolism in the liver. In addition to smoking, there are other risk factors for developing lung cancer. These include exposure to asbestos and heavy metals, such as nickel, and fibrotic disease of the lung. Air pollution is a significant factor in the development of lung cancers, and it is often said that living in London has the equivalent effect on lung cancer incidence to smoking five cigarettes a day. Similarly, proximity to industrial pollution has a significant impact upon mortality rates. Radiation, both therapeutic radiotherapy and background radon levels, increases the risk of lung cancer. As with so many other tumour groups, there is significant interest in the molecular biology of lung cancer. Amongst the first observations of the molecular changes in lung cancer were mutations in the Ras family of oncogenes, which have guanosine triphosphatase (GTPase) activity and are important as second messengers linking events between the cell membrane and nucleus. The history of the molecular biology of lung cancer reads almost like a contemporaneous commentary on the development of our understanding of the molecular biology of cancer, and the next alterations to be discovered were mutations in the tumour suppressor genes Rb and p53 present in at least 80% of all small cell lung cancers. Loss of heterozygosity of a number of chromosomes has also been observed in small cell lung cancer. These include chromosomes 3, 9, 12, 13 and 17. The changes in chromosome 17 involve the c-erb-B2 oncogene and this has led to the development of new therapeutic approaches to the management of lung cancer. More recently, observations of abnormal DNA methylation of the cyclin D2 gene has been described in approximately 60% of small cell lung cancer cell lines. The cyclin D2 gene has a primary function in cell cycle regulation and has recently been brought to the general public’s attention because of the awards of the 2001 Nobel Prizes to the scientists involved in this discovery who included Sir Paul Nurse. Sir Paul Nurse according to The Sun is “the David Beckham of science”. He later became the director of CRUK (Cancer Research UK) but that did not stop him saying that Margaret Thatcher did “a good job of ruining British science”. The survival for early stage lung cancer is much better than if the disease is diagnosed late, so early detection by screening has long been advocated. Neither plain chest X-rays nor sputum cytology has been found to be sufficiently sensitive, but there is hope that low-dose CT scans may be. The potential disadvantages of this approach include the cost, the high false positive rate and the radiation exposure. There are currently two large randomized controlled trials underway of low-dose CT screening. Patients with lung cancer generally present with a cough or haemoptysis. This may be associated with weight loss and symptoms of metastatic cancer (Box 2.2(e)), such as bone pain (Figure 26.4) or jaundice. Patients with symptoms suggestive of lung cancer should be referred promptly by their general practitioner to a specialist chest physician. One of the concerns of oncologists in the 1990s was the lack of referral on from specialist chest physicians to oncologists, with patients regarded somewhat as property. One of the major changes that we have seen in the third millennium has come about as a consequence of the central promotion of the philosophy of the multidisciplinary team. As a result, there is multispecialty input into the management of lung cancer patients and it is the view of these authors that the care of lung cancer patients has generally improved throughout the country. Figure 26.4 Pathological fracture of the mid-humerus in a patient with metastatic non-small cell lung cancer. The fracture has been pinned with an intramedullary nail. The signs of lung cancer are many and of particular interest is the observation of clubbing of the fingers occurring in squamous cell lung cancer. The aetiology of finger clubbing, which is associated with hypertrophic osteoarthropathy and polyarthralgias, has been postulated as including the secretion of parathormone (PTH) by tumours and also, more recently, the ectopic secretion of platelet-derived growth factor (see Figures 39.6 and 39.7). Other clinical abnormalities may include Horner’s syndrome (Figure 26.5) or hoarseness, which are pointers to inoperability as a result of nerve entrapment by the tumour of the sympathetic chain and recurrent laryngeal nerves, respectively. Dysphagia may occur as a result of mediastinal lymph node enlargement. Paraneoplastic syndromes are commonly associated with lung cancer, particularly the small cell carcinoma variant. These include cutaneous syndromes of dermatomyositis and acanthosis nigricans, the neurological complications of peripheral neuropathy, cerebellar ataxia and the Eaton–Lambert syndrome (see Chapter 39). The endocrine features of ectopic PTH, adrenocorticotrophic hormone (ACTH) and antidiuretic hormone (ADH) secretion are all spectacular in their presentations. Investigations should include a full blood count, liver function tests, chest X-ray (Figure 26.6) and sputum cytology. Bronchoscopy is organized and should proceed within a few days (Figure 26.7). Biopsies and washings are then obtained and examined microscopically. By these means, a histological diagnosis will be achieved. Diagnosis may not be achieved in the context of peripheral lesions and if this is the case, then needle biopsies under CT scanning or fluoroscopic imaging should be arranged (see also Figures 2.6, 40.1, 40.2, 40.3, 40.4, 40.5, 40.6b, 40.10 and 40.11). There are a number of different variants of lung cancer, and these histological classifications are important in that they define the patient’s further treatment. The main histological variants are squamous cell carcinoma, small cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma and large cell carcinoma (Figures 1.6, 1.7, 26.8, 26.9, 26.10 and 26.11). For treatment purposes, tumours are described as being either small or non-small cell lung cancers. These constitute 95% of primary lung neoplasms. Squamous cell carcinoma accounts for approximately 20% of lung cancers, with adenocarcinoma accounting for 40% and small cell carcinoma for 15% of all lung tumours. Approximately 10% of lung cancers are of mixed histology. Rarer variants include carcinoid tumours, lymphomas and hamartomas. Figure 26.5 (a) Left unilateral ptosis and miosis (constricted pupil). The other features of Horner’s syndrome are enophthalmos (sunken eye) and anhidrosis (no sweating). It is due to loss of sympathetic innervation due in this case to a Pancoast tumour of the left lung apex affecting the T1 nerve root (b, c) (also associated with ipsilateral wasting of the small muscles of the hand). Horner (1831–1886) was a Swiss ophthalmologist; Pancoast (1875–1939) was an American radiologist. Figure 26.6 Chest X-ray of a 67-year-old woman with T2N2M0 small cell lung cancer showing a right upper lobe primary lesion with extensive ipsilateral and contralateral hilar lymphadenopathy. Figure 26.7 Appearance at bronchoscopy of a primary non-small cell lung tumour blocking the right main bronchus. Figure 26.8 Squamous cell lung cancer. Lung cancer staging is determined usually by the TNM classification. Staging should include a CT scan of the chest and abdomen, a radioisotope bone scan, a liver ultrasound and ideally a positron emission tomography (PET) scan. Although not carried out routinely, examination of the bone marrow by aspiration and trephine in small cell lung cancer shows the presence of metastases in 95% of patients. Pulmonary function tests to assess vital capacity are essential, both to assess operability, and to ensure that the patient is not left with profound breathlessness following lung resection. Non-small cell lung cancer may be treated with either surgery or with radiation treatment. Surgery is only possible for patients with limited stage disease; that is, T1N0M0 and T2N0M0 disease, and a small number with T2N1M0 tumours. There is increasing surgical enthusiasm for operating on more extensive tumours, and it is not uncommon to find patients with T3 disease proceeding to surgery. However, the results of this approach are usually poor. The increasing use of CT–PET scanning prior to surgery provides more accurate tumour staging and has reduced the number of patients undergoing “open and shut” thoracotomies for inoperable tumours. Figure 26.9 Adenocarcinoma of lung. Figure 26.10 Small cell lung cancer. Figure 26.11 Bronchoalveolar cancer of the lung. Bronchoalveolar cancer is now often known as adenocarcinoma with lepidic growth. Lepidic means scaly and refers to the pattern of tumour growth in the terminal airways of the lungs. The United Kingdom falls below the European average in terms of the number of people proceeding to surgery because of issues of resource availability in terms of scans and surgeons. Surgery has a significant morbidity and mortality, and operability depends upon lung function prior to resection, together with cardiac status and the presence of other major illnesses. It is estimated that approximately 30% of patients with non-small cell carcinoma of the lung have operable tumours. The 5-year survival for this group of patients is variably quoted at between 5% and 40%. A review of 2675 patients gave a five-year survival of 30%. There is a subgroup variation in survival, depending upon pathological staging and histology. For example, if those operable patients with adenocarcinoma are considered, the expectation for survival ranges between 38% and 79% and averages 65% at 5 years. If, on the other hand, operable patients under 40 years of age are considered, survival rises to 70%. Radical radiotherapy, that is, radiotherapy given with curative intent, is considered for those patients who have inoperable disease by virtue of a poor medical state rather than spread of the cancer. Five-year survival figures of 6% were reported in a review of 1487 patients. Conventionally, patients receive 6000cGy over a 6-week period. More rapid treatment regimens are used, particularly in the north of England, and similar survival figures are found. For the majority of patients with more advanced cancer, radiotherapy is only used to palliative symptoms, which might include haemoptyses, breathlessness or chest pain. Radiotherapy is given according to various prescriptions; some radiotherapists advise a single dose of 1000–1500 cGy, others 3000 cGy in 10 fractions over 2 weeks. Radiotherapy, too, has side effects, and these include tiredness, oesophagitis and skin changes. There is an increasing role for chemotherapy in the management of lung cancer, both as adjuvant therapy following surgery, neoadjuvant treatment prior to surgery, in combination with radiotherapy in stage III disease and as palliative therapy for advanced disease. The optimum treatment for advanced lung cancer depends upon the histological classification (nonsquamous or squamous) and the presence of driver mutations of genes such as epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) for which specific inhibitors are available. This approach has been rather grandly named “personalized genotype directed therapy”. In general in the absence of a specific mutation, chemotherapy is given as a doublet of two drugs, one of which is permetrexed and cisplatin if the tumour is nonsquamous. For tumours harbouring activating mutations of EGFR, oral tyrosine kinase inhibitors such as erlotinib and gefitinib are indicated as first-line therapy. Side effects are reported, the most common of which is an erythematous skin reaction, and the occurrence of this rash seems to be associated with tumour responsiveness. Tumours with an ALK fusion oncogene may be treated with crizotinib, an oral tyrosine kinase inhibitor that targets ALK. What was once a Cinderella disease waiting for her prince has now emerged from the shadows with the availability of several new drugs of promise to be bestowed upon her, provided her dowry is bountiful, as the cost of these new drugs is considerable. Small cell lung cancer is an entirely different disease from non-small cell lung cancer. It is very rare for patients to have localized small cell lung cancer, and approximately 95% of patients with small cell lung cancer have metastatic disease at presentation. The most important modality of treatment for small cell lung cancer is chemotherapy. The current chemotherapy programme of first choice is etoposide and cisplatin. Approximately 80% of patients have an initial response to chemotherapy with this and similar programmes, and this generally includes a complete remission rate of up to 60% of patients. However, the great majority of small cell lung cancers will recur after chemotherapy. Untreated, the median survival is 3 months. With treatment, 10–20% of patients will survive for 2 years and 5% for 5 years. Small cell lung cancer is associated with many paraneoplastic syndromes, due to secretion by the tumour of specific growth factors and hormones. One of the most common is hyponatraemia, due to inappropriate secretion of ADH. This is treated by water restriction, tetracyclines or the vasopressin receptor antagonist, tolvaptan. Steroids are prescribed in high dose for the treatment of polymyositis, Eaton–Lambert syndrome and the peripheral neuropathies associated with small cell lung cancer. Ectopic ACTH secretion may require high-dose therapy with adrenal enzyme-blocking drugs such as metyrapone and ketoconazole. Unfortunately, these two agents have toxicity in the dosages used and may make the patient feel awful. In this context, adrenalectomy may be rarely required. Case Study: A charlady with a rash.

Lung cancer

Epidemiology

Smoking and prevention

Percentage of all cancer registrations

Rank of registration

Lifetime risk of cancer

Change in ASR (2000–2010)

5-year overall survival

Female

Male

Female

Male

Female

Male

Female

Male

Female

Male

Lung cancer

12

14

2nd

2nd

1 in 18

1 in 14

−13%

−14%

9.3%

7.8%

Pathogenesis

Screening

Presentation

Pathology

Staging and grading

Treatment

Treatment of non-small cell lung cancer

Treatment of small cell lung cancer

Treatment of paraneoplastic syndromes

ONLINE RESOURCE

ONLINE RESOURCE

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree