(1)

Department of Pathology Beckley Veterans Medical Center (West Virginia), McGuire Veterans Medical Center, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA, USA

Lung

Key Morphological Features of Well-Differentiated Adenocarcinoma

Ragged glandular/papillary structures

Expansive growth pattern (Figs. 8.1 and 8.2)

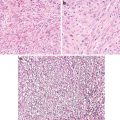

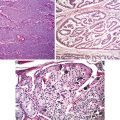

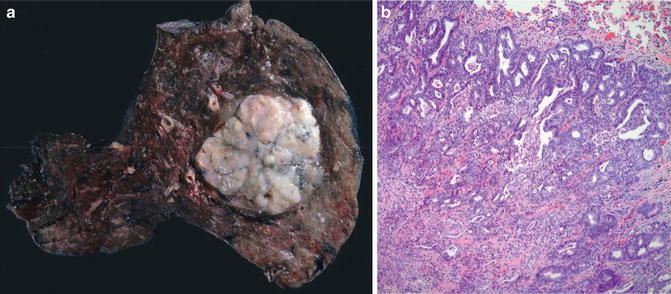

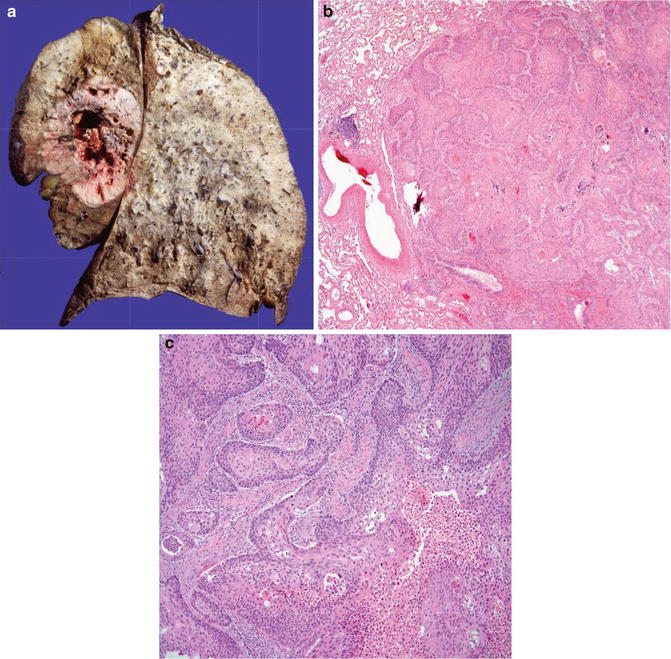

Fig. 8.1

Adenocarcinoma. Well circumscription at both gross and microscopic levels (Tumors and Tumor – Like Conditions of the Lung and Pleura, Elsevier/Saunders, 2010 with permission)

Fig. 8.2

Well-differentiated adenocarcinoma. Expansive (destructive) growth pattern. Note ragged glandular structures (Tumors and Tumor – Like Conditions of the Lung and Pleura, Elsevier/Saunders, 2010 with permission)

Discussion

Most pulmonary adenocarcinomas present with a mixed histological and cytological picture. Traditionally, they have been graded depending on the degree of gland or papilla formation. In 2011, the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer/American Thoracic Society/ European Respiratory Society recommends that pulmonary adenocarcinomas should be graded based on the predominant growth pattern rather than the least differentiated components as for most other carcinomas [1]. The glandular structures of well-differentiated pulmonary adenocarcinomas resemble more clefts or slits than genuine glands. Reflecting the tremendous plasticity of pulmonary stem cells which eventually give rise to more than 40 different cell types in adult lungs, adenocarcinomatous cells can assume many different cellular shapes which might be present in a single tumor [2, 3]. The vast majority of well-differentiated pulmonary adenocarcinomas show features indicating Clara cell or type II pneumocyte differentiation. The tumor cells are bland with ample cytoplasm except for prominent nucleoli. Characteristically, they have protruding and frizzy luminal surface (papillary) borders [3–5]. Consistent with their Clara cell differentiation, this cellular characteristic of adenocarcinomas contributes to the cleft/slit appearance of malignant glands.

Rather than having an infiltrative growth pattern, pulmonary adenocarcinomas are well circumscribed with an overall irregularly lobular appearance [6]. Presumably, the circumscription and cleft-like morphology result from a unique epithelial–mesenchymal interaction evidenced in the lung organogenesis in which the fetal respiratory epithelium seems to adapt and fill available spaces created in the mesenchyme [7–9]. Thus, tumor growth and invasion are dependent on the myofibroblasts at the invasive fronts. The fibrous front at the periphery of the adenocarcinomas might be the driving force in tumor invasion instead of being a restraining force for tumor growth as the traditional dogma stipulates. Supporting evidence is emerging that the activated pulmonary myofibroblasts play an important role in cancer invasive nests in that they lead and cheer the epithelial cells on in the process of invasion [8] (Fig. 8.3).

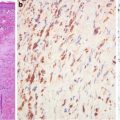

Fig. 8.3

The leading role of stromal myofibroblasts in tumor advance

Thus, in the lungs, primary malignant tumor invasion is not manifested as an infiltrative process. Instead, it is defined as an expansive, destructive growth pattern in which the normal, highly differentiated alveolar structures are replaced by tumor structures. Except for rare cases of colloid adenocarcinoma which are characterized by mucin pools distending alveolar spaces and dissecting the alveolar walls, alveolar structures should not be present in the tumor body. Importantly, alveolar filling (aerogenic spread) and lepidic growth patterns are not considered evidence of invasion. And interstitial thickening which can be present in metastatic carcinomas is uncharacteristic of primary pulmonary carcinomas. This claim is in line with the 2011 International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer/American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society Recommendation [1]. The society recommends discontinuation of the term of bronchoalveolar carcinoma (BAC). Instead it spits the former BACs into four entities: adenocarcinoma in situ, minimally invasive adenocarcinoma, invasive mucinous adenocarcinoma, and lepidic predominant non-mucinous adenocarcinoma depending on the tumor cell type and size and the size of the invasive component. If vascular or pleural invasion or necrosis is present, the tumor should be called lepidic predominant adenocarcinoma rather than minimally invasive adenocarcinoma regardless of the size of the invasive component.

Differential Diagnosis

Benign Mucus Gland Adenoma

Mucous gland adenomas are rare and present as endobronchial masses. Even though they can form complex cystic, tubular, and papillary structures, no invasion of the bronchial wall is evident. The cells are cytological benign.

Because pulmonary adenocarcinomas rarely present as an endophytic mass, the main issue here is to rule out low-grade mucoepidermoid carcinomas. Benign mucous gland adenomas do not have squamous and intermediate cells.

Alveolar Adenoma

Present as a peripheral nodule, alveolar adenomas contain dilated alveolar spaces filled with eosinophilic material. The septa are thickened by spindle cell-rich mesenchyme. They lack a destructive invasion pattern.

Mesothelioma and Adenomatoid Tumor of the Pleura

Mesotheliomas rarely present as a well-circumscribed mass, and pseudomesotheliomatous adenocarcinomas are fairly uncommon. A panel of immunostainings (CEA, B72.3, MOC31, and TTf-1) are required to make the distinction in difficult cases.

Rare cases of adenomatoid-like adenocarcinomas can be differentiated from adenomatoid tumors by lack of expansive invasion in the latter.

Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Primary pulmonary squamous cell carcinoma variants can have cystic, adenomatoid-like, or syringomatous patterns. They usually lack the slit-like appearance with protruding and frizzy luminal borders characteristic of adenocarcinomas.

Salivary Gland-Type Tumor

Because of their rarity in the lung, they are frequently misdiagnosed as non-small cell carcinomas particularly in small biopsies. Importantly, they present as a well-circumscribed, endobronchial mass. Familiarity with their characteristic growth patterns facilitates their recognition.

Key Features of Well-Differentiated Pulmonary Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Well-circumscribed squamous mass

Expansive growth pattern (Fig. 8.4)

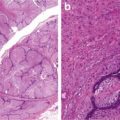

Fig. 8.4

Squamous cell carcinoma with well circumscription and expansive growth pattern (Tumors and Tumor – Like Conditions of the Lung and Pleura, Elsevier/Saunders, 2010 with permission)

Discussion

With the exception of rare exophytic variant of squamous cell carcinoma in which no invasion of the bronchial wall is present, the vast majority of pulmonary squamous cell carcinomas share with their adenocarcinoma counterparts two important morphological features: well circumscription and expansile invasion pattern. As discussed in the preceding section, these shared features are probably resultant from the employment of an embryonic/fetal mechanism in tumor growth and invasion [7–9]. In a form of so-called collective migration in which the tumor cells migrate in a whole group rather than in single cells, the leading cells in the invasive cell nests are guided and cheered on by the activated myofibroblast vanguard [9]. Like in adenocarcinomas, alveolar filling, lepidic spreading, and septal thickening are incompatible with such an alliance.

Whereas pulmonary adenocarcinomas show features indicating differentiation toward Clara cells and/or type II pneumocytes, squamous cell carcinomas are believed to arise from basal cells located in the human bronchus and bronchioles and differentiate along the squamous linage. Unlike the former in which in situ lesions are usually absent, squamous cell carcinomas frequently contain precursor lesions. And this feature can be used in the distinction between primary and metastatic squamous cell carcinomas.

Awareness of the variety of different growth patterns of squamous cell carcinomas is important in order not to mistake them for adenocarcinomas or adenosquamous carcinomas. The variants can have cystic formation and adenoid and syringomatous structures and even clear cells. When in doubt, a panel of immunostainings (p63, keratin 5/6, TTF-1) should be applied.

Differential Diagnosis

Squamous Papilloma, Papillomatosis, Invasive Papillomatosis

Pulmonary squamous papillomas are rare endobronchial proliferations and are associated with human papilloma virus. Typically, they present as an exophytic mass with only mild cytological atypia. Problem arises when the lesion is affected by dysplasia or even carcinoma in situ and when there is involvement of the underlying glands. With papillomatosis, there is a greater degree of cytological atypia and a greater tendency to show an inverted growth pattern (inverted papilloma) and alveolar space involvement (invasive papillomatosis) [10]. These lesions are differentiated from squamous cell carcinoma by their smooth outlines and lack of bronchial and/or parenchymal invasion (destruction).

Squamous Metaplasia or Dysplasia Involving Glands

These lesions do not form a mass and the involved glands have a smooth outline. No destruction of the bronchial wall and/or pulmonary parenchyma is evident.

Primary Pulmonary Adenocarcinoma and Adenosquamous Carcinoma

As discussed in the adenocarcinoma section, primary adenocarcinomas have a slit appearance with ragged luminal borders. This feature allows their distinction from squamous cell carcinoma with prominent cystic changes and adenomatoid/pseudoglandular or syringomatous patterns.

Key Morphological Features of Atypical Carcinoid Tumor of the Lung

Mitotic figures 2 to 10/10 HPF

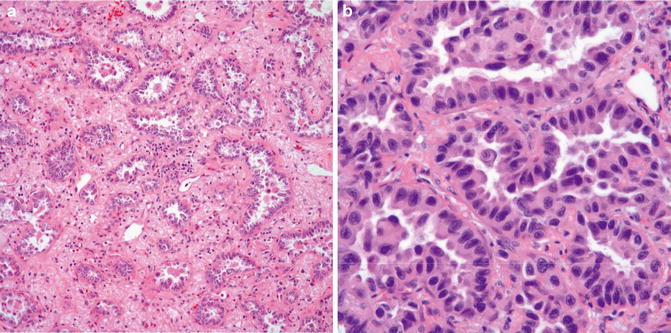

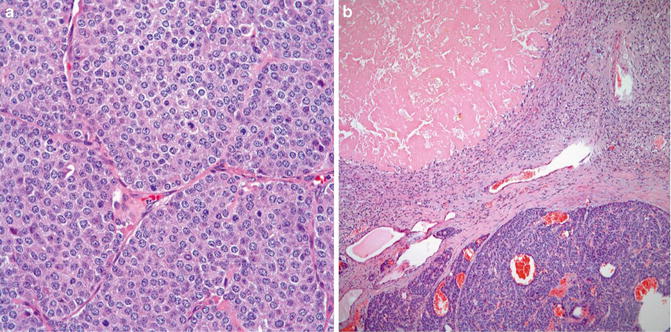

Necrosis (Fig. 8.5)

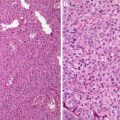

Fig. 8.5

Atypical carcinoid. Note mitotic figures (a) and necrosis (b) (Tumors and Tumor – Like Conditions of the Lung and Pleura, Elsevier/Saunders, 2010 with permission)

Discussion

In contrast to the three-tier classification for gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumors in which mitotic activity is the only criteria for the distinction of NET G1 and NET G2 tumors, pulmonary neuroendocrine tumors are divided into four tiers: carcinoid, atypical carcinoid, small cell carcinoma, and large cell carcinoma [11]. Carcinoids and atypical carcinoids apparently share similar molecular changes which are different from small cell carcinomas and large cell neuroendocrine carcinomas. They have been called well-differentiated and moderately differentiated neuroendocrine carcinomas respectively even though they share virtually identical histopathological and cytological presentations. Histopathologically, they manifest as organoid, trabecular, insular palisading, ribbon, rosette, and even glandular patterns. Typically, the tumor cells are uniformly small to medium size with moderate amount of cytoplasm and contain round nuclei with characteristic salt–pepper chromatin pattern and occasionally small nucleoli. They can also present as variants which are composed of spindle, oncocytic, mucinous, clear, and even melanocytic cells.

The differentiation between carcinoid tumor and atypical carcinoid is the mitotic activity greater than 2 to 10/10 HPF and/or necrosis in the latter [12, 13]. The necrosis can be punctuate or infarct-like. Most of atypical carcinoids meet the two criteria. Cases of with necrosis, but containing less than 2 mitotic figures/per 10 high power fields are called atypical carcinoid. Importantly cellular pleomorphism (neuroendocrine atypia) has no place in the differentiation and they are separated from tumorlets by their size of greater than 0.5 cm in greatest dimension. The high neuroendocrine tumors have their characteristic histological and cytological features allowing their differentiation from carcinoids and atypical carcinoids.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree