Chapter Outline

Plain Language Summary 403

Introduction 404

Public Perceptions of Screening 404

The Conventional Approach to Information Provision 406

The Need for Shared/Informed Decision Making in Screening 406

What It Means to Make an Informed Decision About Screening 407

Supporting Shared/Informed Decision Making With Decision Aids 408

Alternatives to Individual Informed Choice 409

Communicating About Overdiagnosis 410

Informed Choice in Breast Screening: Making It Work 412

Communication in Context 414

Conclusion 415

Glossary 416

References

Plain Language Summary

Breast cancer screening has been going on for many years now, and research suggests that most women in the community feel positive about screening as a way to reassure them that they are well or to find early signs of cancer that can then be treated. Women have been told a lot about the potential benefits of screening, such as helping some women to avoid dying from breast cancer. But more recently, experts have gained a better understanding of the potential downsides of screening. In particular, some of the women who go for breast screening will be diagnosed and treated for a cancer that would never have caused them any trouble if it were not found through screening. This is called overdiagnosis (or overdetection).

Putting together the research about the chances of benefit and harm from screening, experts have moved toward the view that women in the community should be given the opportunity to consider the important information about screening for themselves and make up their own minds about whether it seems worthwhile. The final decision is likely to vary from woman to woman, as it depends on how she personally weighs up the pros and cons. This idea—that people should have a say in what is the best healthcare for them—fits with a broad approach called shared decision making, which is about encouraging people to be involved in health decisions together with their doctor. In many countries, women are offered breast screening directly through an organized program so they do not necessarily discuss it with a doctor. Therefore, we often use the terms informed decision making and informed choice, rather than shared decision making, in this context. Regardless of the term or setting, a key feature of these approaches is making sure women are aware of important things that could happen if they choose to screen or not screen.

Decision aids are tools designed to support people in getting the best information and deciding what is the best thing to do in a particular situation—for example, deciding whether to screen. In this chapter, we discuss research on decision aids and other ways of informing women about screening and finding out their thoughts and feelings toward it. We also discuss the challenges involved in moving to an informed choice approach. More work is needed to figure out the best ways of achieving good-quality, informed decision making for women who are considering breast screening.

Introduction

Cancer screening leads to a complex array of potential consequences for participants. Quantitative estimates of the outcomes of breast screening are outlined elsewhere in this book, so in this chapter we focus on informed and shared decision making. Policy makers face a difficult task in weighing the value of different screening outcomes and judging whether the benefits outweigh the harms. It has been argued that the balance between benefits and harms in breast cancer screening may be considered a close call on which reasonable individuals may vary in their choices. These judgements are at least partly driven by the values of the people making the decisions. The fact that the values of policy makers may not accord with those of individuals who are subsequently offered screening underscores the need for balanced, evidence-based information to be presented to members of the public to enable them to participate in screening decisions. A woman’s choice to attend screening or not should be determined by how she values the small possibility of a large clinical benefit (ie, extension of life) compared with the higher probability of undesirable events such as unnecessary investigations and overtreatment. After all, the woman who undergoes screening must live with the decision and its repercussions.

Public Perceptions of Screening

Achievement of informed decision making in mammography screening faces several challenges, not least for women themselves. There are widely held positive attitudes and often uncritical support for mammography and screening generally. A landmark 2002 survey that documented widespread public enthusiasm for cancer screening in the United States, with 87% of respondents considering routine cancer screening “almost always a good idea,” was partially repeated in a large British sample in 2012 with very similar results. Also, a 2013 systematic review of patient or public expectations of the benefits and harms of medical interventions found that participants tended to overestimate benefits and underestimate harms of a broad range of treatments and tests including breast cancer screening.

Studies employing qualitative methods such as interviews and focus groups have been useful in eliciting women’s reasoning about different aspects of screening and their own participation. Table 16.1 provides examples of women’s attitudes to mammography using selected quotations from research participants. Though there may be cultural influences on screening attitudes, many beliefs recur across socioeconomic and cultural boundaries.

| Theme | Example Statement About Breast Screening | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Enthusiasm for testing | I feel that it is very important whether you are 30 or… 80 [that] you have any tests that you can. | Schonberg |

| I do know that an intelligent person needs the tests routinely, just to make sure everything is cool. | Denberg | |

| Faith in sensitive technology | Once you have the mammography you think “well, they’ve checked it now, that’s that done”… so you know there’s nothing there. | Griffiths |

| Machines that are cleverer than you are looking at you every three years which is a reassurance really. | Griffiths | |

| Value of reassurance | I feel happy having a mammogram, seeing some kind of in depth look at you, to see if you’re all right | Griffiths |

| [The] greatest benefit is learning you don’t have cancer. | Denberg | |

| I feel good when I receive that letter and all is well. Then I feel safe. | Solbjor | |

| Attitudes to risk | If someone objected to having it done, why they’re taking their own life in their hands I guess. | Silverman |

| Even if statistical risk (of getting breast cancer) is low I still want screening, there is still a chance. | Davey | |

| Trust vs skepticism | I just have a trust that the NHS wouldn’t haul us all out if statistically there wasn’t some evidence that, by and large, some people get saved, you know, and that not many people get disadvantaged. | Waller |

| If my doctor told me not to have a mammogram, I would think something is wrong with her. | Allen | |

| Accepting without question | I just think, something that you’ve got to have done. They send the letter through the door, up to you to just go. I don’t necessarily think about it. | Griffiths |

| Yes I’ve always been and it doesn’t worry me. At a certain age, you get a letter from the doctor to attend that sort of thing. I don’t really read about it all. | Griffiths | |

| Anxiety about results | But of course, when you receive that letter you’re a bit tense anyway about what it’ll tell… Before you open the envelope, you feel a sting, like. | Solbjor |

| Is it or isn’t it, do I have this? … The recalls are traumatic… I try not to worry about it, but I still do. | Greco | |

| Critical views on testing | Personally I am of the opinion that you shouldn’t cross your bridges until you come to them. | Osterlie |

| If it’s the case that you don’t feel anything from it, then you should let sleeping dogs lie. | Lagerlund |

As Table 16.1 shows, taking the opportunity for early detection through breast screening is perceived as a way of minimizing potential regret, whereas failure to be screened puts one at risk of a preventable death. Women acknowledge some anxiety about going for screening mammograms, awaiting their results, and having the follow-up tests that false-positive results entail. Some are concerned about the possibility of false-negative results, but many women express strong confidence in the sensitivity of mammography and emphasize the sense of reassurance gained from receiving the “all clear” ( Table 16.1 ). The reassurance of being cancer-free that a normal mammogram result provides may be a key motivator for women to undergo screening, but this reassurance is sometimes false. Moreover, publicity about screening may be partly responsible for raising breast cancer anxiety in the first place, making it questionable whether anxiety reduction can legitimately be considered a benefit of screening.

The Conventional Approach to Information Provision

The public perception of mammography as undeniably valuable is partly due to the persuasive impact of decades of screening promotion campaigns by the health sector. Public health campaigns and messages about cancer screening over many decades have largely reflected a positive view of screening widely held among public health organizations, professional associations, patient advocacy groups, academics, and clinicians. The main approach has been to deploy powerfully persuasive communication tools to convince individuals to screen, with the overall goal of maximizing screening uptake in the population. A standard “recipe” for such communication has been described as follows: induce feelings of fear and vulnerability, then offer hope by framing screening as a simple way to protect oneself. Also consistent with this screening communication approach is presenting “a lopsided view” with an emphasis on (often exaggerated) benefits and minimization of harms. Such communications have created strongly positive views of screening in the community, which in turn feed normative expectations that screening is the “right” thing to do.

This simplistic positive messaging has increasingly come under criticism in recent years. Several international reviews have pointed out that information materials produced and distributed by breast screening services and other relevant groups have overestimated benefits and underplayed harms. The direct communications women receive about breast screening, as described above, occur within a broader context of media stories about medical testing that frequently overlook harms. The heated debates that occur among researchers and health professionals do not necessarily filter through into the public sphere. It is therefore unsurprising that women in screened societies find the idea of scientific uncertainty about breast screening difficult to accept, and are skeptical about attempts to raise awareness of controversies. Nevertheless, research suggests that many women do desire better information. In a Swiss survey, 89% of respondents wanted information on limits of mammography screening and 82% wanted to know reasons why some people oppose screening.

The Need for Shared/Informed Decision Making in Screening

There is now growing consensus that harm and benefit information must be communicated clearly and transparently to women offered mammography screening, so that they can make informed decisions. Screening can trigger a cascade of serious and stressful interventions with lasting implications; therefore, cancer screening decisions are a good example of where helping people to be engaged and involved in decision making is valuable. Experts familiar with the evidence on breast screening recognize that women may weigh things up differently depending on their context and personality—some might appropriately decline screening while others consider the risks acceptable and choose to do it. The importance of this is even greater due to the fact that screening involves offering an intervention to apparently healthy people, as opposed to providing symptomatic patients with medical help they are seeking out.

As outlined above, the task of informing the public in a transparent way has largely been performed inadequately thus far. This necessitates a shift in the approach to screening communications such that efforts are focused on educating people and respecting their informed decisions, rather than persuading them to a particular course of action as if there were an a priori best choice for each individual.

What It Means to Make an Informed Decision About Screening

Shared decision making is a highly influential model of how patient involvement in medical decision making can be conceived. It has been defined as follows : “Shared decision making enables a clinician and patient to participate jointly in making a health decision, having discussed the options and their benefits and harms, and having considered the patient’s values, preferences and circumstances. It is not a single step to be added into a consultation, but a process that can be used to guide decisions about screening, investigations and treatments.” While shared decision making is applicable to many (if not most) clinical decision situations, it is especially important where a preference-sensitive decision is involved. As discussed above, choosing whether to undergo breast cancer screening may be considered such a decision.

Both shared decision making and the related term, informed decision making, can be used to encompass the broader concept of people’s involvement in decision making about their health and healthcare. Shared decision making, as defined above, is conceptualized in terms of patient–clinician consultations in which both parties have input. But many health decisions are made outside of the clinical encounter and without any direct input from a healthcare provider. Deciding whether to accept or decline a screening offer made within a population-based screening program is an example. In this case, informed decision making might be considered the more appropriate term.

Statements endorsing informed decision making are strengthening across the medical literature and health policy landscape. Across a range of clinical contexts, incorporating patient preferences in decision making is recommended as a core aspect of fulfilling the fundamental principles of ethical medical practice. Yet despite a growing consensus that people should be provided with information to enable informed choice, there remains little agreement on precisely what this means in practice.

One way in which informed decision making has been operationalized in research is through the construct of informed choice, which relates to whether people’s decisions in a specific health context are consistent with their informed values or attitudes. Informed choice may be assessed by combining measures of a person’s knowledge, attitudes, and actual choice. For example, an informed choice about whether to undergo screening may be defined as one in which knowledge is adequate, with screening attitudes and intentions being consistent (ie, positive attitudes with positive intentions, or negative attitudes with negative intentions). This conceptualization of informed choice, in terms of knowledge, attitudes, and choice made (in this case measured as intentions), is presented in Table 16.2 .

| Adequate Knowledge | Positive Attitude | Intending to Screen | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Informed Choice-Adequate Knowledge and Consistent Attitudes+Intentions | |||

| Accept screening | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Decline screening | ✓ | × | × |

| Partly Uninformed Choice | |||

| Accept | ✓ | × | ✓ |

| Decline | ✓ | ✓ | × |

| Accept | × | ✓ | ✓ |

| Decline | × | × | × |

| Completely Uninformed Choice | |||

| Accept | × | × | ✓ |

| Decline | × | ✓ | × |

An essential aspect of defining an informed choice is the decision maker’s knowledge of the potential for benefit and harm from the whole screening process. But even if experts agree broadly that some such understanding is necessary, exactly what level of knowledge is sufficient for making an informed decision is subject to varying opinions and hard to pin down. Critics of “the quantitative imperative” have claimed that giving numerical risk information (ie, probabilities of specific benefits and harms) is appropriate for some situations and patients, but not others, because many people may have trouble understanding it. Yet prominent experts assert the centrality of quantitative information within the scope of necessary knowledge about possible outcomes of options in preference-sensitive decisions, arguing that knowing the approximate chances, if not exact probabilities, is crucial.

Supporting Shared/Informed Decision Making with Decision Aids

Methods are available with the potential to achieve better shared and/or informed decision making in breast screening. Decision aids can address the need for better communication of important possible outcomes of breast screening. These are interventions designed to support people in making decisions about treatment or screening when there is more than one reasonable option available, with benefits and harms that people may value differently—in other words, decisions where personal preferences are relevant. Decision aids make the decision explicit (eg, to be screened or not), describe why choice exists, provide information about the options and their associated outcomes, and are intended to help people consider and deliberate about the options from their own personal perspective. Some decision aids include explicit methods for helping users to clarify their values in relation to the decision (values clarification exercises), but the evidence supporting these is uncertain as studies have found mixed results regarding whether they improve decision making.

When presenting quantitative information about decision outcomes, such as the frequencies of important benefits and harms, risk communication experts recommend using either simple percentage (eg, x %) or simple frequency formats (eg, x in 100, where x is a whole number) that explicitly specify the reference class over time. Icon arrays (or “pictographs”) are a type of visual graphic display representing the numerator and denominator together via differently colored filled circles arranged in a matrix, thus depicting the part-whole relationship. Visual displays such as icon arrays are supported by a solid body of research evidence and considered best practice. Presenting numerical information in pictographs has been shown to improve comprehension, including among people with low literacy and numeracy.

Extensive randomized controlled trial evidence in a variety of settings has shown that decision aids improve knowledge and accuracy of risk perceptions, stimulate people to take a more active decision making role, and can improve congruence between the chosen option and the person’s values. Studies have also demonstrated that decision aids can improve the rate of informed decision making about participation in screening programs, including those for cancer. For example, two Australian randomized trials of mammography screening decision aids for women aged 40 and 70 (ie, outside the national screening program’s target age range) showed that the interventions increased knowledge and reduced the proportion of women who remained undecided. Amongst participants who made a decision, older women’s screening intentions and behavior were not altered; for younger women, fewer of those viewing the decision aid intended to start screening now compared to controls, but most were still in favor of screening.

Although current guidance directs clinicians to involve patients in decisions, some are concerned that taking a more active role in screening choices is too daunting or burdensome for lay people. Breast screening program staff thought the information in a mammography decision aid might be too detailed and cause worry, but users considered it clear and understandable, with 97% of participants completing the trial. A trial to evaluate a bowel cancer screening decision aid for adults with low education and literacy achieved an 85% consent rate in a socioeconomically disadvantaged population, with 93% of those randomized actually completing the trial. The decision aid increased by 22% the proportion of people making an informed choice, providing further evidence that informed decision making about screening can be accessible to the wider community.

Alternatives to Individual Informed Choice

Research suggests that a structured, balanced presentation of health information can empower people to assume a more active decision-making role than they initially intend. Nevertheless, some women may not wish to individually evaluate detailed information on the outcomes of mammography screening, including quantified risk data, when they are deciding whether to take part. Determining the extent to which there is a need for promoting individual-level deliberation about this particular health decision could be based on examining the distribution of preferences amongst fully informed women. In turn, these preferences could be elicited in various ways. One strategy known as “community sampling” requires fully informing a random sample of eligible women and asking each person whether she would choose screening. A somewhat different method involves engaging a representative “citizens jury” to deliberate together in considering benefits and harms. Citizens juries are a method of deliberative democracy which can be used to engage citizens in formal iterative dialog on important and complex problems. These methods provide balanced factual information to people with diverse perspectives and potentially conflicting views, and create opportunities to discuss issues freely and test competing claims. A deliberative citizens jury approach has been demonstrated to be a feasible way of eliciting a well-informed, considered community view in the context of mammography screening policy as well as in prostate cancer screening.

Diversity of screening preferences amongst fully informed women would support the need for detailed individual consent, whereas a community consensus in favor of screening would suggest that alternative approaches may be appropriate. For example, providers could assist people to “consider an offer” of screening. This involves helping people evaluate the trustworthiness and personal relevance of the screening offer, while acknowledging that it might reasonably be declined. Personal preferences determine whether the individual requires further information such as data on outcomes or community views. The “consider an offer” concept provides the basis for the novel approach adopted in England since 2013 regarding information for people invited for cancer screening. Each eligible person receives a letter of invitation (which may be seen as a recommendation in itself). Alongside the letter, people receive a leaflet developed at arm’s length from the screening program, with balanced information about benefits and harms. The leaflet aims to encourage the reader to assess the offer of screening, rather than simply encouraging screening, and to make it clear that declining the offer may be reasonable.

Communicating about Overdiagnosis

One highly contentious issue in breast screening is overdiagnosis (or overdetection). The medical community has long recognized that diagnosing and treating inconsequential disease is an important potential harm of screening. However, public awareness about nonprogressive cancer is extremely limited. A 1997 postal survey among US women showed that only 6% knew that some breast cancers grow so slowly as to not affect health. In 2010 an online survey of Americans aged 50–69 who had been invited to cancer screening by their doctor found that only 8% of women had been informed about the risk of overdiagnosis and overtreatment. Similarly, in an Australian telephone survey conducted in 2014, just 10% of women who reported having had a mammogram said they were told about the risk of overdiagnosis.

Questions of how information about overdiagnosis in breast screening could be communicated to women, and how such information may affect decisions about whether to undergo screening, have been identified in the screening and shared decision making literature as important targets for empirical investigation. The first research to address these questions in depth was an Australian qualitative study involving a series of focus groups held in 2011. During the focus groups, the investigators explained the concept of overdiagnosis and explored women’s responses to different estimates of its rate—1–10%, 30%, and 50%—reflecting the varied estimates published at that time. Participants were women in the age range eligible for mammography screening. These women had virtually no awareness of overdiagnosis in breast screening and reacted with surprise, raising many questions about the new information. Most women reached a basic understanding of overdiagnosis by the end of these sessions, and they expressed diverse attitudes towards. Participants suggested a range of ways in which their approaches to screening might be affected, from no change whatsoever to potentially declining screening altogether. Their screening intentions overall were quite sensitive to the magnitude of overdiagnosis, with higher estimates more likely to prompt careful consideration. It was interesting that a number of women interpreted the information as more pertinent to how screen-detected cancers should be managed, rather than whether to undergo screening in the first place. Overall, most participants felt that information on overdiagnosis was important and should be available to women to enable informed decision making. Focus groups conducted in 2012 in England echoed the findings that women were unaware of overdiagnosis but could understand the concept, recognized the information as important, and believed women should be informed about it. There was, however, a broad consensus that the risk of overdiagnosis with screening was preferable to the risk of delayed diagnosis without it.

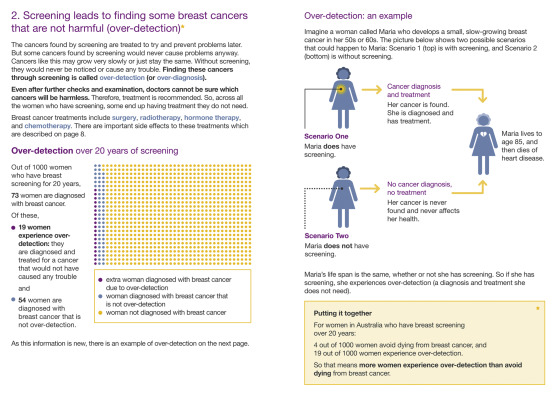

The above evidence from qualitative studies of women’s understanding of overdiagnosis highlighted the urgent need to investigate whether a meaningful explanation of overdiagnosis could be condensed into a concise written format, and to evaluate its effects quantitatively. A randomized controlled trial in Australia assessed the potential consequences of informing women about overdiagnosis using a decision aid. This paper-based resource presented the probabilities, cumulated over 20 years of screening, of avoiding death from breast cancer, experiencing overdiagnosis, and having a false-positive—three outcomes that are considered important to decisions about mammography screening. Fig. 16.1 shows extracts from the decision aid illustrating how it explained the concept and risk of overdiagnosis. By comparing this with a control decision aid omitting the overdiagnosis component, the trial addressed the question of whether including the overdiagnosis content specifically improved the rate of informed choice.