Chapter Outline

Plain Language Summary 190

Introduction 190

Late-Life Breast Cancer Risk 194

Understanding the Benefits and Risks of Mammography Screening Among Older Women 195

Potential Benefits of Mammography Screening Among Older Women 195

Risks of Mammography Screening Among Older Women 198

Efficacy of Breast Cancer Treatment Among Older Women 200

Estimating Remaining Life Expectancy for Older Women 201

Screening and Cognitive Impairment 203

Screening Intervals for Older Women 204

Other Screening Modalities 204

Clinical Breast Exam 204

Digital Mammography and Computer-Aided Detection (CAD) 204

Digital Breast Tomosynthesis 205

Factors Influencing Older Women’s Screening Decisions 205

Discussing the Benefits and Risk of Screening With Older Women 206

Recommendations for Discussing Stopping Mammography Screening With Older Women 206

Decision Aids on Mammography Screening for Older Women 207

Quality Metrics 209

Similarities to Other Cancer Screening Tests 209

Questions/Future Work 209

Conclusions 210

List of Acronyms and Abbreviations 210

References

Plain Language Summary

It is not certain if mammograms benefit women aged 70 or older. While the chance of breast cancer increases with age, breast cancers tend to grow more slowly among older women. Experts think that a small breast cancer found on an older woman’s mammogram would not have caused problems for 5 to 10 years and some of the breast cancers found would never have caused problems. Meanwhile, the average women aged 75 lives 13 more years; those in poor health live less long. Experts recommend that clinicians think about how long an older woman may have to live before recommending mammography screening. Guidelines recommend against screening women who are unlikely to live 10 years and experts encourage women ≥70 years in good health to make an informed decision about whether or not to be screened. The pros to getting a screening mammogram are that mammograms are more likely to find breast cancers when they are small, improving an older woman’s chances of only needing minor surgery. In addition, although doctors are unsure that getting a mammogram will lower an older woman’s chances of dying from breast cancer, some studies suggest that 2 out of 1000 women aged 70 in good health that continue getting mammograms for 10 years may avoid breast cancer death. However, approximately 100–300 of these women will experience a “false alarm.” These women experience an abnormal mammogram but additional tests do not show breast cancer. It is estimated that 20–50 of 1000 women that continue to be screened will experience a benign breast biopsy as a result of having been screened and the majority of older women find their experience with breast biopsies stressful. In addition, around 13 of 1000 women screened will be diagnosed with a breast cancer that would never otherwise have shown up or caused problems in an older woman’s lifetime. Since it is difficult to predict which breast cancers will progress and which will not, nearly all older women undergo treatment for breast cancer. Breast cancer treatment for older women usually involves removing the lump of breast cancer from the breast and taking hormonal pills for approximately 5 years. Some older women are also treated with radiation therapy and a few older women in excellent health are treated with chemotherapy. While most older women do well after surgery, many experience side effects from the hormonal pills and from treatment with radiation and/or chemotherapy. To decide whether or not to get a mammogram, older women must consider their health, their risk of breast cancer, and how strongly they feel about the possibility of reducing their risk of death from breast cancer in 10 years with the greater chance of experiencing a false alarm or being diagnosed and treated for a breast cancer that otherwise may not have caused problems. There are educational tools available to help older women weigh these trade-offs and clarify their values and preferences about whether or not to be screened with mammography.

Introduction

Women ≥70 years are the fastest growing segment of the United States (US) population and breast cancer incidence increases with age peaking between ages 75–79 years ( Table 8.1 ). However, few women ≥70 years were included in the randomized controlled trials evaluating mammography screening and whether or not to screen these women for breast cancer is controversial. National and international guidelines and policies regarding mammography screening for older women vary ( Table 8.2 ). Most US guidelines recommend that clinicians consider an older woman’s health and/or life expectancy before recommending screening and some guidelines specifically recommend not screening women with less than 10-year life expectancy. The United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends biennial mammography for women ages 50–74 years and states that there is insufficient evidence to recommend screening to women aged 75 and older. Instead, the USPSTF recommends that if mammography screening is offered to women ≥75 years, these women should understand the uncertainty about the balance of benefits and harms before being screened. Despite these recommendations, Medicare has covered biennial screening mammograms for all women aged 65 or older regardless of their age or health since 1991 and has covered annual screening mammograms for women aged 65 and older since 1998. The Affordable Care Act also includes coverage of annual screening mammograms for all women regardless of their age or life expectancy.

| White a | Black a | Hispanic b | Chinese c | Japanese c | Hawaiian/Filipino c | Pacific Islanders c | United Kingdom d | Sweden e | Canada | Australia | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||||||||||

| 55–59 | 273.8 | 275.2 | 185.7 | 197.1 | 322.2 | 537.3 | 236.6 | 266.2 | 248.9 | 220 | 264.5 |

| 60–64 | 359.2 | 328.5 | 215.1 | 167.5 | 400.7 | 523.8 | 284.4 | 318.7 | 324.8 | 320 | 334.9 |

| 65–69 | 430.7 | 382.4 | 251.2 | 182.2 | 352.2 | 558.2 | 292.1 | 378.5 | 363.4 | 320 | 378.3 |

| 70–74 | 445.4 | 396.7 | 284.6 | 183.4 | 359.3 | 567.8 | 233.0 | 296.4 | 336.9 | 310 | 301.0 |

| 75–79 | 462.3 | 405.4 | 275.7 | 192.0 | 358.9 | 651.3 | 203.6 | 331.9 | 274.3 | 310 | 307.9 |

| 80–84 | 436.3 | 395.8 | 252.3 | 223.3 | 353.9 | 389.0 | 148.3 | 369.7 | 307.6 | 270 | 296.3 |

| 85+ | 365.0 | 371.9 | 203.9 | 224.7 | 205.2 | 294.9 | 101.2 | — | — | 270 | 306.9 |

a Data from NCI’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program from 2006–2010.

b Data from NCI’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program from 1990–1996 (most recent available for Hispanics).

c Data from NCI’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program from 1998–2002 (most recent available for Asian Ethnicities).

d Data from Thames Registry first breast cancer rates 2005–2009.

e Data from Statistics Sweden first breast cancer rates 2006–2010.

| Organization | Year Guideline Issued | Mammography Screening Recommendations |

|---|---|---|

| United States | ||

| American Board of Internal Medicine Choosing Wisely Campaign | 2013 | Do not recommend cancer screening in adults with life expectancy of less than 10 years. |

| American Cancer Society | 2015 | Women should continue screening mammography as long as their overall health is good and they have a life expectancy of 10 years or longer. If performed, recommend screening every 2 years. |

| American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists | 2011 | Women aged 75 or older should, in consultation with their physicians, decide whether or not to continue mammographic screening. Medical comorbidity and life expectancy should be considered. If performed, recommend screening every year. |

| American College of Radiology | 2008 | Screening should stop when life expectancy is <5 to 7 years or when abnormal results would not be acted on due to age or comorbidities. If performed, recommend screening every year. |

| National Comprehensive Cancer Network | 2013 | In older women, mammography screening should be individualized, weighing its potential benefits/risks in the context of the patient’s overall health and estimated longevity. If a patient has severe comorbid conditions limiting her life expectancy and no intervention would occur based on the screening findings, then the patient should not undergo screening. If performed, recommend screening every year. |

| US Preventive Services Task Force | 2015 | Evidence is insufficient to assess the additional benefits and harms of screening mammography in women 75 years or older. No recommendation (I statement—If the service is offered, patients should understand the uncertainty about the balance of benefits and harms). If performed, recommend screening every 2 years. |

| Other Countries | ||

| Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care | 2011 | A tailored approach to mammography screening is warranted in women aged 70 years or older. If a woman desires to continue screening mammography, it is justified if her life expectancy exceeds 5–10 years (weak recommendation; low quality evidence). If performed, recommend screening every 2–3 years. |

| National Health Service, United Kingdom | 2010 | Women aged 74 or older can request continued mammography screening but do not receive routine invitations. If performed, recommend screening every 3 years. |

| Netherlands National Institute for Public Health and the Environment | 1998 | Women up to age 74 are invited to be screened with mammography every 2 years. Women aged 75 or older can request to be screened but do not receive routine invitations. |

| The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners | 2014 | Women aged 75 or older (changed from age 70 in 2015) can request continued mammography screening, but they are not targeted to be screened by BreastScreen Australia. Women in this age group should balance the potential benefits and downsides of screening, considering their general health and whether they have other diseases or conditions. If performed, recommend screening every 2 years. |

| Other Countries Combined | ||

| China | 2009 | Women up to age 59 are invited to be screened with mammography every 3 years in China. |

| Finland, Greece, Hungary, Saudi Arabia, Singapore | Women up to age 64 are invited to be screened with mammography every 2 years in these countries. (In Hungary, women are invited to be screened every year). | |

| Ireland | 2000 | Women up to age 65 are invited to be screened with mammography every 2 years in Ireland. |

| Belgium, Denmark, Germany, Iceland, Italy, Luxembourg, Norway, New Zealand, Poland, Portugal, Spain, Switzerland, Uruguay | Women up to age 69 are invited to be screened with mammography every 2 years in these countries. (In Uruguay, women are invited to be screened every year). | |

| France, Israel, Sweden | Women up to age 74 are invited to be screened with mammography every 2 years in these countries. | |

| Japan, Korea | Women up to age 75 are invited to be screened with mammography every 2 years in these countries. | |

a Recommendations are based on each organization’s literature review, consensus process and expert opinion.

In the US, screening is opportunistic. Women initiate screening for themselves or are encouraged to get screened by their physicians. In Canada, Australia, and most European countries screening is implemented through a national screening program where women receive mailed invitations to be screened at regular intervals based on their age. Within these countries, determining the appropriate age to stop inviting older women to be screened is controversial. In Canada, women cease to be invited for mammography screening by age 70. In the UK, the Netherlands, and Australia women stop receiving invitations to be screened by age 74 or age 75 ( Table 8.2 ). Older women may continue to request to be screened even after they stop receiving screening invitations; however, data from the UK suggest that the majority of older women (82%) stop being screened once they stop receiving screening invitations. In the US, however, approximately 50% of women ≥75 years continue to be screened, including 36% of older women with ≤5 year life expectancy. In the setting of limited data from clinical trials and disparate policies, experts recommend that decision-making around mammography screening for older women consider their risk of breast cancer , their life expectancy , and their values and preferences based on a reasonable and realistic understanding of the benefits and risks of screening. This chapter will review what is known about each of these components of high quality mammography screening decisions for older women.

Late-Life Breast Cancer Risk

While it is well known that the risk of breast cancer increases with age ( Table 8.1 ), there are few tools available to help inform older women of their individualized risk of breast cancer beyond their age-based risk. The Breast Cancer Risk Assessment Tool (BCRAT), also known as the Gail model, is the most commonly used breast cancer prediction model in primary care settings. The model gives older women that are in good health and that are regularly screened a reasonable estimate of their probability of breast cancer within 5 years. For example, based on the model a 75 year old white woman at average risk has 2.2% probability of breast cancer in 5 years. However, the model does not discriminate well which women are more or less likely to develop breast cancer. This means that many women categorized at high risk by the model will not get breast cancer while a number of women categorized at low risk will still get breast cancer.

To determine a woman’s 5-year probability for developing breast cancer, the BCRAT considers a woman’s baseline risk of breast cancer based on her age and race using age and race/ethnic specific population breast cancer incidence rates from NCI’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program ( Table 8.1 presents recent incident rates available through SEER as well as breast cancer incidence rates in Canada, Australia, UK, and Sweden). The model then adjusts a woman’s probability of breast cancer by considering whether or not a woman has several risk factors for breast cancer including younger age at menarche, older age at her first live birth, a history of first degree relative (mother, sister, daughter) with breast cancer, a history of breast biopsy, and a history of atypical hyperplasia on a breast biopsy. However, some of the risk factors included in the BCRAT, for example, age at menarche and age at first birth, may become less predictive of breast cancer as women age due to the number of years that have passed since these factors influenced older women’s estrogen levels. In addition, factors that may be more indicative of recent exposure to endogenous estrogens such as obesity, high bone mass, high breast density, postmenopausal hormone therapy, may be more predictive of late-life breast cancer but are not included in the BCRAT. Also, although the model considers a woman’s risk of death in 5-years from nonbreast cancer causes, the model assumes that the age-specific hazard of dying from nonbreast cancer causes is the same for all individuals in an age group. However, there is known to be significant variations in older women’s health and life expectancy with age.

The model may also overestimate the influence of some risk factors on an older woman’s probability of breast cancer. Some of the risk factors included in the model, such as family history of breast cancer and a history of benign breast biopsy, are associated with increased mammography use. Meanwhile, mammography may find some breast cancers before symptoms develop and may even find some cancers that would never have caused problems. Therefore, mammography use may lead to an increased estimated risk of breast cancer among older women who are screened. As a result, some of the increased risk of breast cancer associated with family history and history of breast cancer may be confounded by increased use of mammography among older women with these risk factors. Similarly, whether race is an independent risk factor for late-life breast cancer is uncertain. White women aged 75–84 have a higher incidence of breast cancer than African American women in this age range ( Table 8.1 ), but this difference may also be a result of differential use of mammography by these women.

Due to these limitations, new breast cancer risk models that consider factors associated with late-life breast cancer risk (eg, obesity, higher bone mass) and an older women’s individualized competing risk of nonbreast cancer death are needed to better inform decision-making around breast cancer screening for older women. In the meantime, to estimate their risk, older women should consider their age-based risk (see Table 8.1 ) and slightly increase or decrease their probability of breast cancer based on their family history of breast cancer, their history of benign breast disease, body-mass index, breast density, competing mortality risks, and use of mammography.

Understanding the Benefits and Risks of Mammography Screening Among Older Women

Potential Benefits of Mammography Screening Among Older Women

The benefit of mammography screening is finding breast cancer at an early, asymptomatic stage when treatment is expected to be more effective in reducing breast cancer mortality than if treatment were begun later when the cancer presented symptomatically. While mammography screening has been shown to reduce breast cancer mortality by 15% among women in their 40s and by 32% among women in their 60s, whether mammography screening reduces breast cancer mortality for women ≥70 years is not certain. Of the randomized controlled trials of mammography screening, only the Swedish Two-County trial included women ≥70 years and this study only included women up to age 74. A subgroup analysis of women 70–74 years in this trial did not find a significant reduction in breast cancer mortality among women 70–74 years screened every 24–33 months compared to women not offered screening (relative risk: 1.12 95% CI (073–1.72)). To better understand the effectiveness of mammography screening among women 70–73 years, beginning in 2009, the UK’s National Health Service Breast Screening Program has randomized the roll-out of extending the age at which women are invited for mammography screening from age 69 to age 73 in a large 10-year cluster randomized controlled trial. It will be several years before the results of this study will be available. In the meantime, investigators have attempted to estimate the effectiveness of mammography screening among women ≥70 years through retrospective cohort studies, simulation models, and by extrapolating data from the randomized controlled trials of mammography screening that included younger women.

Even in the absence of clinical trial data, there are reasons to hypothesize that mammography screening may be beneficial to women ≥70 years. First, breast cancer incidence increases with age and screening tests tend to be more beneficial in a population where the condition is prevalent. Second, the performance (sensitivity, specificity) of mammography screening may improve with age. In the US, the sensitivity of digital mammography screening among women in their 70s has been reported to be around 86–88% with a specificity of 93%, while the sensitivity of mammography screening among women in their 50s is reported to be around 81% with a specificity of 91%. In addition, improvements in breast cancer survival seen since 1980 have lagged behind for older women and lower rates of mammography use among women ≥75 years may partially explain this finding. Between 1980 to 1997 the adjusted risk of breast cancer death in newly diagnosed women decreased by 3.6% per year for women <75 years; however, the adjusted risk of breast cancer death decreased only by 1.3% per year for women ≥75 years. This is despite the fact that older women tend to have more favorable tumor characteristics (more estrogen receptor positive (ER+) tumors, lower proliferative rates, and normal p53). Reassurance about one’s health may be another potential benefit of mammography for older women; however, there may be more cost-effective ways for physicians to reassure older women about their health.

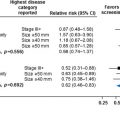

Retrospective studies evaluating mammography screening among older women

Several retrospective studies have compared breast cancer survival among older women who are screened regularly compared to older women who are not screened or are not screened regularly to better understand mammography’s impact on older women’s survival. Using these methods, McCarthy et al. found that 5-year breast cancer mortality was lower among women 67–84 years (but not for women ≥85 years) that had undergone mammography screening within 2 years of diagnosis compared to women who had not been screened, even after adjusting for comorbidity. McPherson et al. found that among women 65–101 years diagnosed with breast cancer that all-cause mortality was lower among women whose breast cancers were detected through screening compared to women whose breast cancers were detected nonmammographically, except for women with severe or multiple comorbidities. Badgwell et al. found that among women ≥80 years diagnosed with breast cancer, 5-year breast cancer survival was 94% among women who received ≥3 mammograms during the 5 years before breast cancer diagnosis, 88% among women who received 1–2 mammograms in the 5 years before diagnosis, and 82% among women that were not screened. Combined, these studies suggest a survival benefit for mammography screening among older women, especially for older women in good health.

It is important to note, however, that these studies were limited by lead-time, length time, and selection biases inherent in observational data that may explain the positive results. Lead-time bias occurs when screening results in identification of disease earlier than it would have otherwise been detected, thus lengthening survival time between diagnosis and death, without actually altering when death occurs. A retrospective study examining differences in survival following a breast cancer diagnosis among women that were screened compared to women that were not screened that does not adequately account for lead-time bias will overestimate the benefits of mammography screening since a woman whose disease is diagnosed earlier through screening will live longer following diagnosis simply due to earlier detection. Length bias occurs because screening increases the number of slowly progressive or nonprogressive cancers that are identified. These tumors may never become a symptomatic problem (overdiagnosis) but are treated because they are detected. Comparing survival after diagnosis of such tumors to tumors detected nonmammographically will overestimate the benefits of mammography. Selection bias occurs because older women in good health are more likely to choose to be screened and adjusting for comorbidity may not completely account for baseline differences in mortality risk between these women. In fact, the Badgwell et al. study found similar improvements in nonbreast cancer survival among women ≥80 years that were regularly screened compared to women ≥80 years that were not screened suggesting that selection bias may explain the breast cancer survival benefits found to be associated with mammography in this study.

Simulation models

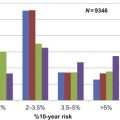

Due to the limitations of retrospective studies, investigators have also attempted to estimate the benefits of mammography screening in older women through microsimulation models. These models make assumptions about the natural history of breast cancer and the efficacy of screening mammography among older women and consider the relationships between breast cancer incidence and mortality, competing causes of death, mammography test characteristics, and breast cancer treatment effects. To understand the effects of continuing biennial and/or annual screening beyond age 69 to age 79 years, Mandelblatt et al. compared results from six different well-established simulation models that use US data. On average, they found that approximately two additional breast cancer deaths are averted and 24 life years gained (LYG) per 1000 older women that continue to be screened. Van Ravesten et al. used three of these microsimulation models to examine the effects of continuing mammography screening from age 74 up to age 96 years. They found that the benefits of screening outweigh the risks up until age 90. At age 74 years, screening results in 7.8 to 11.4 LYG per 1000 women screened which decreases to 4.8 to 7.8 LYG at age 80 years per 1000 women screened and to 1.4 to 2.4 LYG at age 90 per 1000 women screened. By age 90, the life years gained by mammography screening are counterbalanced by the loss of quality of life associated with false positive tests and overdiagnosis. Barratt et al. used a Markov simulation model and national data from Australia on use of mammography, follow-up testing after screening, and on breast cancer and overall mortality to compare women aged 70 who choose to continue biennial screening for 10 years with women who choose to stop being screened at age 69. Similar to Mandelblatt et al., they found that compared to women who stop screening, 2 of 1000 women who choose to continue biennial screening may avoid breast cancer death (6 vs 8 breast cancer deaths per 1000 women who choose to continue screening).

Other studies using simulation models have found that the benefits of mammography screening for older women may be limited to older women with risk factors for breast cancer. Kerlikowske et al. using a Markov simulation model estimated the effects of mammography screening among older women based on their bone density. They found that one of 1064 older women with high bone density that chooses to continue being screened routinely from ages 69 to 79 will avoid breast cancer death. However, they also found that 7143 women with low bone density need to be screened routinely from ages 69 to 79 to prevent one breast cancer death, suggesting that screening is not as effective among older women with low bone density. Schousboe et al. used a Markov microsimulation model to examine the effect of screening women 70–79 years every 3 to 4 years compared to no screening and found that 1–3 fewer women 70–79 years per 1000 die of breast cancer that are screened. However, the benefits of screening were mostly limited to older women with high breast density, a history of breast biopsy, and/or a family history of breast cancer. In addition, in a cost-effective analysis using simulation modeling, Mandelblatt et al. found that screening women to age 79 or to a life expectancy of 9.5 years is cost-effective, especially for older women at higher risk of breast cancer.

Combined, the data from modeling studies suggest that approximately 2 women ≥70 years that choose to continue to be screened with mammography annually or biennially for 10 years may avoid breast cancer death and that the benefits of screening may be greater for older women at higher risk of breast cancer. It is important to note; however, that these modeling studies must make several assumptions about the natural history of breast cancer and the efficacy of mammography screening among older women due to the lack of available data on these outcomes for older women. Therefore, there is more uncertainty when using these models to estimate the effects of mammography screening among older women than for younger women. When breast cancer is assumed to be slower growing and higher rates of overdiagnosis of breast cancer as a result of mammography screening are used in the models, simulation models find that mammography screening is less effective among women ≥70 years.

Other methods for estimating the efficacy of mammography screening among older women

Investigators have also examined incidence rates of advance stage breast cancers before and after implementation of screening within a population to better understand the benefits of screening older women. If mammography screening is effective then advanced stage cancers should decrease in a population while early stage cancers increase after screening is implemented. Using this approach, investigators in the Netherlands examined the incidence of early and advanced stage breast cancer before and after the implementation of mass screening among women aged 70–75 years which occurred in 1998 in the Netherlands. They found that after screening was implemented the incidence of early stage cancers increased by 1.46% while the incidence of advanced stage cancers decreased only by 0.88%. For each “prevented” advanced stage tumor there were 19.7 overdiagnosed breast cancers or breast cancers that would not otherwise have caused problems or symptoms during an older woman’s lifetime. Critics of this method of assessing the benefits of screening argue that it overestimates overdiagnosis because it does not adequately account for lead-time bias.

To understand the time-lag to benefitting from mammography screening among older women, Lee et al. examined pooled data from five of the randomized controlled trials evaluating mammography screening. They excluded trials that were considered biased in a Cochrane review of randomized controlled trials of mammography screening and they excluded trials that did not include women >50 years. They found that on average 10.7 years passed before one death was prevented for 1000 women ≥50 years screened with mammography. Therefore, they concluded that mammography screening is most appropriate for older women with >10 year life expectancy.

Summary

Based on the available existing data, approximately 2 women out of 1000 age ≥70 years with life expectancy greater than 10 years may avoid death from breast cancer that chooses to continue being screened with mammography biennially for 10 years. These benefits may be more likely for older women at high risk of breast cancer such as older women with a family history of breast cancer or a history of benign breast biopsy.

Risks of Mammography Screening Among Older Women

Potential harms of mammography screening include anxiety resulting from false positive tests, false reassurance from an erroneously negative test, diagnosis of tumors that otherwise would not have shown up in an older woman’s lifetime (overdiagnosis), and complications from work-up and/or treatment of cancer. Among women ≥75 years who undergo biennial screening the cumulative probability of a false-positive mammogram over 10 years ranges from 12–27% and the risk nearly doubles if women are screened annually (48% of women 75 to 89 years screened annually will experience a false positive mammogram). False positive recalls tend to be lower outside the US. While follow-up tests such as diagnostic mammograms and breast ultrasounds are generally low-risk procedures, approximately 10–20% of older women that experience a false positive mammogram will undergo a benign breast biopsy and this procedure can cause distress, scarring and infection. Among 94 US women ≥65 years that experienced a benign breast biopsy, 76% (71/94) reported a negative psychological consequence (eg, lack of sleep) from screening at the time of breast biopsy and 39% (37/94) reported that they were still experiencing a negative psychological consequence of screening six months after their breast biopsy. A stereotactic breast biopsy may be particularly burdensome to older women, due to the amount of time and positioning required to be on the biopsy table, especially for older women with osteoarthritis. Also, older women who rely on family for transportation may feel that they are burdening family for travel to the breast biopsy. Furthermore, experience with a false positive mammogram has been shown conversely to increase older women’s enthusiasm for screening and to increase health care utilization in general.

Overdiagnosis

Overdiagnosis is the major harm of cancer screening for older women since it leads to diagnosis and treatment of tumors that otherwise would never have caused problems in an older woman’s lifetime. A breast cancer diagnosis may be particularly burdensome to an older woman due to increasing comorbidity, frailty, declining social networks, less access to medical information, decreased use of counseling, more experience with loss, and lower socioeconomic status. Older women are also more likely to experience adverse effects from breast cancer treatments. Despite this, few studies have attempted to estimate the proportion of screen-detected tumors among women ≥70 years that are likely overdiagnosed. Quantifying overdiagnosis regardless of a woman’s age remains a challenge. Estimates of overdiagnosis vary from 0 to 50% of screen-detected breast cancers but all estimates are subject to bias and there is debate about the best methodology.

An easy to conceptualize method for estimating overdiagnosis is examining the persistent excess incidence of breast cancer over long-term follow-up among women that were randomized to be screened with mammography compared to women that were not randomized to be screened in the screening trials. Using this methodology, Welch and Black estimated that 24% (95% CI 20–28%) of screen-detected cancers were cases of overdiagnosis based on 15 years of follow-up after the 10 year trial period of the Malmo mammography trial. A randomized controlled trial of mammography screening in Canada of women 40–59 years reported an overdiagnosis rate of 22% for all screen-detected invasive breast cancers after 25 years follow-up. The US rate of overdiagnosis has been estimated to be 22–31% of all breast cancers diagnosed when comparing breast cancer incidence before and after screening was implemented. Combined, these data suggest that around one-fourth of screen-detected breast cancers are overdiagnosed. However, since older women tend to have less aggressive tumors with more favorable biologic characteristics (eg, greater percent of estrogen (ER) positive tumors) and more competing mortality risks, overdiagnosis is thought to increase with age. Furthermore, detection of ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), a noninvasive form of breast cancer, which accounts for approximately 16% of all screen-detected breast cancers among women 70–84 years, likely represents overdiagnosis. This is because only about a third of cases of DCIS are thought to develop into invasive cancer after 10–15 years follow-up and less than 5% of women diagnosed with DCIS will die of breast cancer within 30 years after diagnosis. Meanwhile, the average life expectancy for women aged 75 is 12.9 years, 9.7 years for women aged 80, and 6.9 years for women aged 85.

Using simulation models, van Ravensteyn et al. estimated changes in the rate of overdiagnosis for screen-detected tumors by age. They found that the models estimated 5 to 32% of women 50–74 years that undergo biennial screening are overdiagnosed, compared to 14–36% of women at age 80, and 28 to 41% of women at age 90 years. Barratt et al. also used simulation modeling to estimate overdiagnosis among older women. They found that 41 out of 1000 women aged 70 that continue to be screened biennially for 10 years will be diagnosed with breast cancer (including DCIS) compared to 24 women who choose to stop being screened (37% more breast cancers detected through screening). Excluding DCIS, they found that 35 women that choose to be screened for the next 10 years will be diagnosed with breast cancer (28% more invasive breast cancers detected compared to women who choose to stop being screened).

Summary

Based on available data, it is reasonable to estimate that 10–30% of women ≥70 years who continue biennial screening will experience a false positive test and 10–20% of these women will undergo a benign breast biopsy which is often a stressful experience for older women. In addition, approximately 30% of screen-detected breast cancers among older women are likely overdiagnosed. If we estimate, based on SEER data, that 44 women out of 1000 aged 75 will be diagnosed with breast cancer over 10 years then approximately 13 (30%) of these women will be diagnosed with a breast cancer that otherwise would not have caused problems in their lifetimes (overdiagnosis). However, since it is not possible to know which screen-detected tumors will progress and which will not, nearly all older women undergo treatment for breast cancer.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree