Chapter Outline

Plain Language Summary 347

Introduction 348

Social Aspects of Breast Screening 349

Social Attitudes Toward Breasts and Breast Cancer 349

Sociology of Health and Illness 350

Biomedical Culture 350

Commercial and Institutional Aspects of Breast Screening 351

The Political Nature of Breast Screening 352

Ethical Issues in Breast Screening 352

Maximizing Health Benefits Through Breast Screening 353

Delivering More Benefits Than Harms 359

Delivering the Most Benefit Possible Within the Resources Available 360

Respecting and Supporting Autonomy 361

Honesty, Transparency, and Procedural Justice 362

Distributive Justice 363

Reciprocity 364

Solidarity 366

Conclusion 367

Glossary 367

List of Acronyms and Abbreviations 368

References

Plain Language Summary

Breast screening is a large public health program with a significant reach. It is shaped by existing patterns of acting and reasoning, and challenges us to think differently about society and ethics.

Social attitudes about the breast affect attitudes toward breast cancer. The symbolism of the breast (motherhood, sexuality) means breast cancer is a highly emotive issue and breast screening is a popular media story. This may contribute to the popularity of breast screening. Screening may, in turn, affect social attitudes about breast cancer via its contribution toward increasing public familiarity with this disease. Breast screening has arisen within the context of (and may have contributed toward) increasing tendencies in society to place responsibility for health upon individuals, and to be aware of and averse to risks. Similarly, breast screening has arisen within and may have contributed toward a biomedical culture that exhibits strong support for early detection of cancer, technological innovation, and evidence-based medicine. Breast screening is a powerful public health institution. Part of its success may be due to key stakeholders having multiple reasons to support and promote its continuation, strong breast cancer advocacy, and political popularity.

There are several ethical principles relevant to breast screening. There are debates over the extent to which breast screening respects these principles, and over how to prioritize principles in order to deliver the most ethically justifiable program.

Breast screening should deliver benefits, avoid delivering harms where possible, and should deliver more benefits than harms. It seems likely that breast screening reduces population breast cancer mortality in women aged 50–69 years and delivers a range of harms, but there are debates about the extent and significance of each of these consequences. Benefits and harms appear to be closely balanced. Involving consumers at various levels may help with comparing benefits and harms, and negotiating between principles. Breast screening should deliver the most benefits possible within the resources available. The cost-effectiveness of breast screening compared to other healthcare expenditure is controversial, and cost-effectiveness arguments relating to participation rates may be problematic. Breast screening should respect and support individual autonomy: facilitating informed choice is an important part of this. There is disagreement over the impact of informed choice policies on costs and participation rates, and over how much this matters. Breast screening communications with consumers should be honest, and decision-making procedures should be transparent and just. Breast screening policies may be biased if decision-makers have vested interests, including professional interests. Honest communications may be facilitated by removing participation targets or using independent experts. Vested interests could be declared, or managed by excluding conflicted parties from decision-making. Breast screening should operate justly, providing fair screening opportunities, and achieving fair breast cancer and general health outcomes. Implications of the principles of reciprocity and solidarity for breast screening remain complex and caution is warranted. Like any public health program, breast screening inevitably has social and ethical implications: we suggest these will become increasingly central in future policy and practice.

Introduction

In this chapter we consider the social and ethical dimensions of breast screening. Breast screening is grounded in science, but it is also part of society. Like any large-scale public health program, breast screening exists in a two-way relationship with the society in which it is located, being subject to the values and conventions of that society, but also influencing future social attitudes, values, and practices. We will look at the many ways in which social structures and conventions, and moral and ethical thinking, interact with breast screening policies and practices. Our discussion is in two main sections. First we consider social aspects of breast screening: societal attitudes and ideas that influence or are influenced by breast screening. Second we examine ethical aspects: considerations about right and wrong with regard to breast screening.

Social Aspects of Breast Screening

Social norms and structures interact with breast screening in many ways. They may act as facilitators or barriers to the implementation of and public participation in breast screening, and may themselves be influenced by breast screening policies and practices. Below we discuss key aspects of the interactions between society and breast screening, focusing on those that have been most studied and discussed in academic and lay literature.

Social Attitudes Toward Breasts and Breast Cancer

Breast screening is influenced by more general social norms and values regarding the breast itself. Because the breast is associated with sexuality and motherhood, disease and treatment of this organ is highly emotive and associated with particular fear and anxiety. Women may feel embarrassed about breast disease, and hesitate to seek medical attention for breast symptoms. Breasts, particularly youthful looking breasts, are a popular topic for the media, raising the profile of breast cancer higher than might be expected from its medical impact alone and higher than for any other cancer. This media coverage is an important source of information for many women but is also skewed toward reporting breast cancer in young and attractive women, despite breast cancer incidence being much higher in older women.

Many authors have suggested that both breast screening itself, and public communication encouraging women to participate in screening, have changed the way that breast cancer is understood in society, and may also have changed the profile of the disease itself. Most authors agree that the introduction of screening has coincided with a sharp and sustained increase in breast cancer incidence and prevalence. The rise in incidence may be at least partly due to overdiagnosis. Similarly the rise in prevalence may be inflated by a combination of increased lead time and improved survival as a result of screening, along with contemporaneous improvements in treatment. The impact of this increase on the number of breast cancer patients and survivors has been discussed by many writers, some of whom hold potentially conflicting views. It is suggested that breast screening may have:

- 1.

reduced embarrassment and nihilism about symptomatic disease, thus facilitating earlier presentation;

- 2.

artificially inflated fear of breast cancer death;

- 3.

artificially inflated belief in breast screening benefits; and

- 4.

made women vulnerable to overmedicalization, leading them to demand screening and precautionary treatment even when it is unlikely to be beneficial.

Some authors are particularly critical of the use of fear in breast cancer or breast screening communication. They point to the media presentation of breast cancer as a mysterious, increasing, frightening “epidemic,” predominantly striking premenopausal white women in their prime years. These authors point to the inaccuracy of this depiction, and some suggest it has been deliberately engineered as a tool to encourage participation in screening.

Summary: social attitudes toward breasts and breast cancer

- ●

The symbolism of the breast (motherhood and sexuality) means breast cancer is highly emotive and breast screening is a popular media story, potentially contributing toward attitudes toward breast screening.

- ●

Screening may affect social attitudes about breast cancer via its contribution toward increasing public familiarity with the disease.

Sociology of Health and Illness

Breast screening resonated with general cultural and social trends in the second half of the twentieth century relating to health risks and responsibilities. Many authors note an increasing expectation, beginning in the 1970s and 1980s, that individuals could and indeed, should, make “lifestyle choices” to improve their health. These authors suggest the introduction of breast screening has contributed to a “personal responsibility” model of breast cancer, by providing an opportunity for women to take individual responsibility for breast health. There are two concerns with this model: firstly, the opportunity to participate in breast screening may have become a social obligation, with normative repercussions and judgment against those who do not screen, especially if they get breast cancer. Secondly, there is concern that preoccupation with screening may have deflected attention from studying other methods of breast cancer control such as primary prevention.

Other writers have noted an increasing tendency to subject ourselves to medical attention, including widespread general enthusiasm for testing and screening. Relatedly, sociologists have extensively documented the increasing risk awareness and risk aversiveness that characterizes contemporary society. This seems especially pertinent here, as women have been shown to be particularly aware of themselves as being at-risk for breast cancer as opposed to other conditions, and to overestimate both their risk of dying from breast cancer and the protective benefit of mammography.

Summary: sociology of health and illness

- ●

Breast screening fits with the increasing tendencies of society to place responsibility for health upon individuals, and to be aware of and averse to risks.

Biomedical Culture

Breast screening has arisen in the context of prevailing biomedical paradigms regarding cancer growth and control, the use of technology and evidence in medicine. Breast screening, as an important practice in preventive health and medicine, has arguably contributed to these paradigms. We discuss each of them below.

The first example of the relationship between breast screening and biomedical paradigms relates to the conceptualization of breast cancer as a disease. For decades breast cancer has been (dominantly) understood as having a linear growth pattern progressing from a localized focus of dysplasia or in situ disease, to invasive and potentially metastatic cancer. This helps to explain the inherent acceptability of breast screening as a policy. The most successful methods of control for women without specific genetic abnormalities have been assumed to be early detection and intervention and this has contributed greatly to the widespread support for breast cancer screening among the medical profession. Although this paradigm is still dominant, some writers are challenging its hegemony, suggesting that some breast cancers may regress or adhere to nonlinear growth patterns. It remains to be seen whether these or other theories become more widely accepted and influence the future of breast screening.

Breast screening is seen by some writers as an example of the technological imperative in action: that is, some propose that screening was adopted in part because both women and experts believed in the technology itself. The implication here is that belief in the technology may have been at least as significant a factor in the popularity of breast screening as evidence of benefit. This is particularly discussed in relation to the encouragement of women under 50 to participate in breast screening, despite lack of evidence about benefit for this age group in early randomized controlled trials (RCTs). More recent developments in breast screening suggest that the technological imperative may be losing force as we learn from past experience: newer screening modalities that appear to offer increased test sensitivity are being approached with some caution and concern regarding overdiagnosis.

The rise of evidence-based medicine (EBM) has paralleled the production of evidence about breast screening. Breast screening proved to be highly conducive to epidemiological study, and the large amount of RCT and other evidence generated around this topic was an important reason for its broad acceptance by the biomedical community. In turn, it may be that the perceived success of (evidence-based) mammographic screening programs gave a boost to the EBM approach.

Summary: biomedical culture

- ●

Breast screening has arisen within the context of, and has contributed toward, the culture of biomedicine.

- ●

Breast screening has supported and been supported by approaches to the early detection of cancer, technological innovation, and EBM.

Commercial and Institutional Aspects of Breast Screening

Breast screening has become heavily institutionalized in Western society and culture. Many writers express concern about commercial interests in this process. They point to a range of actors including pharmaceutical companies, equipment manufacturers, professional medical organizations, and corporate donors who are doubtless motivated strongly by the desire to prevent women from dying of breast cancer, but have additional commercial interests.

Breast cancer advocacy is one notable institution related to breast screening. Breast cancer advocacy groups are large, powerful, and highly visible social institutions with recognizable symbols (pink ribbons) and traditions, such as the Komen Foundation Race for the Cure. Although not the first major disease-specific advocacy group (this belongs to HIV) breast cancer advocacy has, arguably, led the way in ensuring that consumer voices are taken seriously as a legitimate form of public opinion and power. Many breast cancer advocacy groups believe strongly in early detection by screening and campaign for screening resources and services. Some authors suggest that the symbolic significance of the breast previously discussed makes it easier to raise funds for breast cancer causes (including breast screening) than for some other conditions, helping to explain the relatively strong funding base and profile for breast cancer advocacy.

Summary: commercial and institutional aspects

- ●

Key stakeholders may have commercial interests that influence their participation in breast screening.

- ●

Breast cancer advocacy is powerful and bolsters support for breast screening.

The Political Nature of Breast Screening

Many authors have ascribed the political popularity of breast screening partly to its easily quantifiable outcomes, which can be readily presented as success stories, but more importantly to its role as a “women’s issue” that will attract votes. Breast screening is seen as a “safe and noncontroversial” women’s issue, unlike, for example, abortion or domestic violence. This is illustrated by the willingness of women in political life to be candid about their breast cancer experiences (think here of Betty Ford or Happy Rockefeller). By contrast when Janette Howard, wife of the then Prime Minister of Australia, was diagnosed with cervical cancer her disease was not made public.

The lively advocacy environment surrounding breast screening also illustrates its political nature and contributes to the frequent politicization of breast screening. For example, when the 1997 Consensus Conference by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) removed its endorsement of routine screening for women aged 40–49 years, suggesting instead that it be a personal decision, many advocates organized against the change. Their political influence was strong enough to encourage the US Senate to pass a resolution urging the NIH to reconsider, and ultimately the NIH re-endorsed routine, annual mammography for this age group. Twelve years later, breast screening again returned to the center of political attention. In 2009 the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) also recommended that screening for younger women (aged 40–49) be an individual choice rather than standard practice, provoking immediate and intense condemnation by advocacy and clinical leaders. The US Department of Health and Human Services quickly issued a statement to distance itself from the recommendations, stating that federal breast screening policy would remain unchanged and assuming that private health insurers would follow their lead. The US federal health insurance program Medicare continues to provide coverage for annual breast screening from age 40.

Summary: politics

- ●

Breast screening tends to be both politically popular and politically contested, which influences the design of policy and practice.

Ethical Issues in Breast Screening

Readers will be familiar with the idea of planning and evaluating screening programs against public health, economic, and perhaps legal criteria. Although many of these evaluative criteria include implicit ethical principles (such as maximizing benefits, minimizing harms, and more recently, respect for autonomy voiced as requirement for informed consent) a formal ethical approach can provide additional value. First, it can provide depth of analysis, making arguments for why principles are important and should be upheld. Second, it draws our attention to additional considerations that have not traditionally appeared in screening ethics frameworks. For example, ethicists focused on screening have not only written about why it might be important to obtain informed consent for screening but also about the tensions between promoting individual health, promoting community health and respecting autonomy. They have also considered the ethical implications of professional, institutional and consumer tendencies to start and, once started, to continue preventive screening programs and to under-recognize the potential for this screening to do more harm than good.

The ethics of screening are made more complicated by its location on the boundary between clinical and public health practice. Although some of the ethical issues faced by clinical medicine versus public health are similar, others are quite different. Many readers will be familiar with the Beauchamp–Childress principles for clinical ethics (respect autonomy, do good, avoid harm, seek justice): in recent years authors have proposed alternative sets of principles for public health ethics. We will consider both clinical and public health principles, beginning with those that are more frequently discussed and debated within breast screening. Note that some of these principles are more contentious, and so require more space to discuss. This is not meant to imply any greater importance, but might suggest these issues are deserving of greater societal debate.

The public health ethics and screening ethics literatures suggest the importance of these ethical issues when evaluating breast screening :

- ●

Maximize health benefits

- ●

Minimize harms

- ●

Deliver more benefits than harms

- ●

Deliver the most benefit possible within the resources available

- ●

Respect autonomy

- ●

Maintain transparency, including communicating honestly

- ●

Distribute benefits and burdens justly

- ●

Uphold reciprocal obligations

- ●

Act in solidarity with others

We will consider each of these in turn.

Maximizing Health Benefits Through Breast Screening

The goal of improving the health of populations is central to public health practice. There has been considerable debate over the degree to which public health policies should deliberately contribute to individual and societal well-being beyond physical health, an issue we will consider later in this chapter. In this section we concentrate specifically on health benefits. In general, a program that delivers greater health benefit can be considered more justifiable, primarily because—in many ethical traditions—good consequences have moral value in themselves. In addition, delivering these benefits keeps the promises implicitly or explicitly made about the program.

Public health is generally characterized as being concerned with health benefits in populations rather than primarily focusing on individuals . In population breast screening, for example, a public health perspective would predominantly focus on the degree to which screening increases the longevity and quality of life of women on average across a population, rather than being concerned with benefit delivered to individual women. It is useful to consider the distinction between benefits to populations and benefits to individuals since it is less clear than it may seem, especially for an activity like screening. This is in part because benefits to populations are of more than one type. They include all of the benefits experienced by individuals added up ( aggregative benefits ) but many public health programs also provide an additional benefit, sometimes called a corporate benefit , that occurs at the population level only. For example, vaccination programs deliver aggregated benefits (all of the instances of personal protection via immunization, added up) but also corporate benefits (the herd immunity that arises only after a certain proportion of the population is vaccinated, and which protects even those who are not vaccinated). The various aggregate and corporate benefits of breast screening are discussed below.

Breast cancer mortality benefits

Breast cancer screening delivers breast cancer (disease specific) mortality benefit for some age groups. The introduction of breast cancer screening into a population has been shown to result in a reduced population breast cancer mortality rate. This is mainly because some women who are screened derive benefit from their participation (the sum of which provides an aggregative benefit) although the existence of breast screening may also provide corporate benefits to women in general (discussed below).

For some public health programs, aggregative population benefit is widely and equally distributed among most people. For example, in vaccination programs where most children participate, the benefit is approximately the same for each child. Not so for the breast cancer mortality benefit of screening: most women who attend breast screening receive no breast cancer mortality benefit at all, and attending screening will not make any difference to whether or not they die of breast cancer. This is because most women, screened and unscreened, will not develop breast cancer. Of those women, screened and unscreened, who do develop breast cancer, many will not die from it if they undergo current treatment regimes. Still others, sadly, will die from it regardless of whether or not they attended screening. It has been calculated that less than one in seven women who are screen-diagnosed and treated for breast cancer receive mortality benefit from their screening. Thus the aggregative disease-specific benefits of screening clearly exist, but are unequally distributed in the population, being derived from a small number of women.

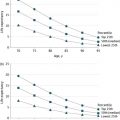

This aggregative benefit from a small number of women remains the dominant driving force behind mammography screening. Recent attempts to quantify breast cancer mortality benefit suggest that screening is less beneficial than was calculated in most of the early RCTs, partly because of revised calculations from the original studies, and partly because of recent improvements in treatment, which reduces the margin for benefit from interventions such as screening. Writers also express concern that breast cancer screening has very little impact on all-cause mortality.

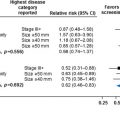

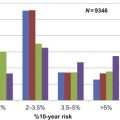

The likelihood of deriving breast cancer mortality benefit from screening may vary between women and between populations of women. Individual women at increased risk of dying from breast cancer will be more likely to derive benefit from screening, and conversely those at decreased risk will be less likely to derive benefit. The latter group includes young women (since they are much less likely to get breast cancer than older women) and women who are more likely to die from other causes (eg, due to age or significant comorbidities). Similarly, populations of women with a higher incidence of breast cancer will derive more absolute mortality benefit from screening, and populations with a lower incidence (eg, communities in many parts of Asia ) will derive less benefit. This raises questions regarding screening policy, and the extent to which programs should consider themselves obliged to focus screening on those subpopulations of women which are most likely to experience an (aggregative) mortality benefit. Thus far, within a given population, outside of age and (uncommon) genetic markers, most risk factors for breast cancer are modest and thus of limited use in stratifying screening. Recent research on risk factors such as family history of breast cancer in first-degree relatives, and personal breast density may alter this. Women in their 40s at high risk of breast cancer may have similar benefits and harms from breast screening as average risk women aged 50–74, and thus might consider screening at an earlier age.

Breast cancer morbidity benefits

Breast cancers identified through screening programs tend to be smaller and more amenable to breast conserving treatment than cancers that present symptomatically. This is often mentioned as a benefit of breast screening programs but is controversial. If the breast cancer detected was destined to progress and become more difficult to treat, then the woman concerned has certainly experienced a morbidity benefit. However some researchers are concerned that many small, asymptomatic cancers identified through breast screening are indolent—cancers that would never otherwise have come to the attention of the woman. If this is so, breast-conserving treatment cannot be counted as a benefit, since no treatment was necessary. This problem of unnecessary diagnosis and management of nonprogressive cancers produces the overdiagnosis in breast screening programs; there is little consensus on how common it is. Overdiagnosis is discussed in more detail later in this chapter. In addition, several writers have expressed concern that screening has led to an increase, rather than a decrease, in mastectomy rates, due to the screen-detection of multifocal noninvasive disease that confers an increased risk of developing invasive breast cancer and is unsuitable for localized treatments. This remains controversial.

Psychological benefits

Since the majority of women are not destined to develop breast cancer, most women will receive a negative screen. While some argue that the reassurance of a negative screen can justifiably be counted as a benefit of screening, others disagree. Those who object give several reasons, including that in some cases the screening result will be wrong (a false-negative), so screening may sometimes deliver false reassurance. More generally, though, since it has been consistently shown that both the fear of breast cancer death and the expectation of mortality benefit from screening are inflated relative to what the evidence would support, it is argued that a woman’s subjectively experienced reassurance from a negative screen may be considerably inflated relative to our best estimates of her objective risk of developing breast cancer. This distorted perception of risk may have at least in part arisen from the communication campaigns of public health communication about breast screening. If this is true, without denying women’s subjective experience of reassurance, we should question the justifiability of including it as a benefit of screening. In addition, a wrong may be done to women if they are implicitly or explicitly misled them about the degree to which they are at risk and the degree to which participating in screening may prevent their death.

Does breast screening offer corporate benefits?

Many people consider that a population’s benefits for cancer screening are accrued only as aggregative benefits: the sum of benefits experienced by (a few) individuals as a result of participating in screening. Others describe several corporate benefits, added benefits that accrue to an entire community as a result of breast screening policies and practices. First, screening promotion campaigns have arguably improved public awareness and knowledge about breast cancer and, as noted earlier, this familiarity with disease may facilitate earlier presentation among women with symptomatic breast disease. Second, operating a breast screening program within a population may generate a sense that society cares about women, and is willing to support them and provide them with services. (This is considered in more detail below.) Finally, although it is impossible to assert a causal link, the introduction of breast screening is widely considered to have catalyzed better breast cancer management, facilitating an improvement in the coordination and operation of breast cancer treatment through better experience, training and monitoring of medical specialists, and the introduction of multidisciplinary team care. This has meant better outcomes and experiences for all women with breast cancer. Note, however, that these latter benefits have, to a large extent, already been delivered and are likely to continue, whatever happens to screening. Thus they seem relevant for an evaluation of past screening programs, but arguably are not relevant to our assessment of how screening should occur in future. This is in contrast, for example, to herd immunity, the corporate benefit of vaccination programs, which depends entirely on their continuing operation.

Summary: benefits

- ●

Breast screening delivers breast cancer–specific mortality benefits and may deliver all-cause mortality benefits.

- ●

Breast screening may deliver morbidity benefits (less aggressive treatments but possibly some unnecessary treatments).

- ●

Consumer reassurance may or may not be a legitimate benefit for many women who participate in screening.

- ●

Introduction of breast screening has stimulated additional, population-wide benefits (eg, improved management) but this may not be a pertinent justification for future screening programs.

Avoiding or Minimizing Harms

Evaluations of public health programs often focus on delivery of benefits. However any intervention on an individual or population can also do harm. In clinical medicine, this concept is covered by the principle of nonmaleficence: avoiding doing harm associated with patient investigation or treatment. While nonmaleficence is an ancient and widely recognized principle of clinical medicine, the idea that public health policies such as screening can do harm is less-well recognized. It may not be possible to completely avoid harms in public health programs, but in general a more ethically justifiable program is thought to be one that minimizes harms for participants and populations.

There are several types of harms common to any screening program. The discussion below relates specifically to breast screening. Some of these are examined in more detail elsewhere in this book.

Inconveniences and financial costs of participation

It is well recognized that participation in breast screening incurs inconveniences and difficulties such as taking time away from work or child care to attend appointments, psychological anxiety, and pain. Although these are generally perceived as being relatively inconsequential, they are persistently cited by consumers as notable aspects of the breast screening experience and policymakers should continue to work toward addressing such concerns. In many countries, a screening mammogram and any associated investigations also incurs financial costs.

Harms related to the test

Radiation harms associated with modern mammographic screening are widely recognized to be acceptably low for women 40 and older. The radiation dose is higher for women who have dense breasts and for women with very large breasts, thus radiation exposure may be more problematic for premenopausal women and large-breasted women, particularly if having frequent (eg, annual) mammographic screening. Greater radiation exposure associated with adding newer tomography screening modalities is currently of concern, and work is continuing to address this.

Harms related to test results

Harms associated with test results include technical faults and false-positive results requiring recall and repeat testing, and false-negative results. Recall for technical faults or false-positive screens deliver physical harms of additional mammograms and possibly fine needle or core biopsies. In addition to physical harm, these also carry risks of psychological harm and, in many countries, extra financial costs. It has been estimated that the psychological distress associated with false-positive mammography can last for over 3 years. The likelihood of a woman receiving a false-positive diagnosis during a lifetime of screening varies greatly with the location and parameters of the screening program. It also accumulates such that a regularly screened woman’s risk of having a false-positive in her lifetime is much higher than her risk of having a false-positive as a result of a single test. False-negative results are much less common but may also cause harm through false reassurance and delayed presentation of symptomatic disease.

Harms arising from the limitations of screening

Some of the cancers diagnosed through breast screening may never progress and, without screening, would not have come to the attention of the individual in her lifetime. This includes both invasive breast cancers and noninvasive breast cancers—ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) and lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS). This phenomenon is called overdiagnosis or overdetection and is discussed in detail in Weighing the Benefits and Harms: Screening Mammography in the Balance, Challenges in Understanding and Quantifying Overdiagnosis and Overtreatment, Treatment of Screen-Detected Breast Cancer: Can We Avoid or Minimize Overtreatment? . At present indolent cancers cannot be distinguished from progressive, potentially lethal cancers, so all cancers are treated. Treatment is generally unpleasant and may be financially burdensome for the individual (eg, in the United States, even those with health insurance suffer considerable “financial toxicity” after a cancer diagnosis due to the rising costs of patient copayments for cancer treatment ). Very occasionally treatment will result in patient death. Thus at a population level, breast screening may be associated with unnecessary morbidity and mortality due to overdiagnosis. Although it is not possible to determine whether overdiagnosis has occurred in any one individual woman, we know that it is one of the harms associated with breast screening because it can be identified at a population level (see chapter: Challenges in Understanding and Quantifying Overdiagnosis and Overtreatment ). Despite intensive research, there is currently no firm consensus on rates of overdiagnosis within breast screening.

Breast screening does not always deliver certainty about breast health: sometimes screening uncovers changes in the breast (such as LCIS and atypical hyperplasia) that are not cancerous, but are associated with increased susceptibility to breast cancer in that individual. That is, unlike DCIS, which is regarded as a nonobligate precursor to invasive cancer, certain “high-risk” lesions (including LCIS and atypical hyperplasias) are widely regarded as indicative of generalized increase in the likelihood of breast cancer. This type of result might be seen as a harm because it produces heightened anxiety about breast cancer, but does not deliver an expected level of certainty about risk to the individual and may require substantial removal of noncancerous breast tissue (eg, single or double mastectomy) to reduce the woman’s risk and anxiety levels to those of an age-matched cohort without identified breast disease.

Are harms justifiable?

There are several important points to consider when evaluating whether or not the harms associated with breast screening are justifiable. These include the size of the harm and how this should be measured, the extent to which harms can be predicted, whether it is possible to minimize harms and if so what other consequences may follow, and finally whether action should be taken to minimize harms. We consider each of these points below.

How much harm?

It has proven difficult to gain consensus on the amount of harm associated with breast screening. As noted above, despite many years of operation and many studies and metaanalyses, there remains substantial variation in calculations of cumulative false-positive and overdiagnosis rates. At least some of the variation may be real: it may be that different screening protocols and different populations produce different amounts of population harm. Some of the variation may be methodological: differences in overdiagnosis calculations may contribute to the considerable disparity between estimates. Writers have urged breast screening experts to reach consensus about how to measure overdiagnosis in order to make progress on this controversial topic.

Anticipating harms

Some harms, particularly false-positives and false-negatives, are well anticipated prior to the implementation of organized screening, and programs only go ahead if and when it is possible to minimize these harms. Other harms are less well anticipated. For example, the possible harms associated with ionizing radiation were unknown when mammographic screening was initially introduced sporadically in the 1950s and then widely implemented through several states in the United States in the 1960s and 1970s in the Breast Cancer Detection and Demonstration Projects. (Since that time, mammography units have much improved and radiation doses considerably reduced.) Similarly, while overdiagnosis was discussed prior to widespread breast screening, it was generally assumed this would not be a significant problem. In particular, overdiagnosis of DCIS was not seriously considered since DCIS is usually impalpable (asymptomatic) and was a rare diagnosis prior to the onset of screening. Recently, there have been calls for researchers to make a more deliberate effort to anticipate, investigate, and report on possible harms associated with proposed (and existing) screening programs particularly in relation to the diagnosis of inconsequential disease.

Minimizing harms

When harms are anticipated (or should reasonably be able to be anticipated), ethical obligations to avoid harming imply that programs should be designed to not only maximize benefits, but also to minimize harms. In the context of breast screening this includes close attention to quality control, and requires careful and ongoing monitoring of screening program procedures, parameters, and outcomes in order to identify and correct technical and procedural problems. Program policies should incorporate activities before and after the testing stage, with identifiable standards and quality checks for all steps including, for example, recruitment and communication, repeat testing, and follow-up. There is some concern that private opportunistic screening providers may not engage with the same quality control standards and parameters that public, nationally organized providers adhere to. Notwithstanding these needs for quality control, the nature of screening means that harms cannot be avoided: minimizing harms from false-positive tests is likely to increase harms from false-negative tests and vice versa. Program operators must decide how to balance their programs such that the various harms are best minimized.

Summary: harms

- ●

Breast screening delivers harms to the participating population.

- ●

There is no consensus on how much harm is delivered by breast screening.

- ●

Close attention to quality control is required to minimize harms.

Delivering More Benefits Than Harms

We have shown above that there are potentially both positive and negative consequences of breast screening: benefits and harms. For most people, having benefits outweigh harms is a necessary criterion for an ethically justified public health program. (We would add: necessary but not sufficient . That is, other morally relevant factors such as autonomy, transparency, and distributive justice should also be considered, and we discuss these and other principles below.) The process of weighing up benefits against harms is multilayered. It includes, in no particular order: quantitative measurements of benefits and harms (which is controversial in breast screening, as discussed above); comparisons between qualitatively different benefits and harms; and the relative weightings ascribed to maximizing benefits and minimizing harms.

Comparing qualitatively different benefits and harms

Benefits and harms may be disparate in nature, making meaningful comparisons difficult. How, for example, should we compare population breast cancer mortality reductions against (possible) population breast cancer morbidity increases? The logic underpinning endorsed public health activities is that they should result in population health benefits that are clearly more substantial than the harms, and this has generally been the case with breast screening. For example, when organized breast cancer screening was introduced in Australia, the benefits from reducing breast cancer deaths was widely accepted to considerably outweigh the harms associated with occasional false-positive or false-negative tests. Since that time, as discussed above, estimates of screening benefit have decreased and anticipated harms have increased and it is now frequently suggested that the benefits and harms accruing from breast screening are closely balanced. In such a scenario, qualitative differences between screening outcomes make comparisons particularly troublesome. Translating screening outcomes into comparable units may have some similarities with the somewhat controversial use of QALYs (quality-adjusted life years) for comparing disease outcomes. It is not clear who might be best placed to make such translations.

Should we prioritize maximizing benefits or minimizing harms?

The relative importance ascribed to maximizing benefits and minimizing harms may vary according to context and individual preferences. In some circumstances, or for some people, avoiding harm may be considered a prioritized principle, that can rarely be traded off against benefit or any other principle. Again, where the differences between benefits and harms are clearly great, personal preferences about the importance of each principle may not significantly affect the outcome of balancing benefits against harms in population-level policymaking. For breast screening, where benefits and harms appear more closely balanced, individual differences in prioritizing each principle may become more important.

Who should decide whether benefits outweigh harms?

Many writers think it important to involve consumers in such calculations. Consumers can be involved at policy level and at a personal participation level. Firstly, deliberative democracy methods, such as citizens juries, can be used to determine public perspectives on comparing qualitatively different benefits and harms, and on the weightings that should be ascribed to maximizing benefits and minimizing harms. The rationale here is that lay people may value and trade off the various possible benefits and harms differently to experts. Secondly, many people suggest that individuals who are considering participating in breast screening can and should be more involved in deciding whether or not benefits outweigh harms in their particular case, because they are best placed to know their own attitudes toward these benefits and harms. Consumer decision-making is valued here for its usefulness as being the best way of deciding between somewhat similar or incomparable outcomes, independent of the intrinsic value of being able to make decisions for oneself (see more on this in the next section on respect for autonomy). This reasoning contributes to new breast screening communications with consumers, that seek to present both benefits and harms and encourage informed choices about screening participation.

Note however, that obtaining informed consent does not remove responsibility from providers to minimize harms, and breast screening policymakers arguably have a duty to deliver screening policies that the majority of the target population will accept. Many consider that benefits of screening remain substantial enough to outweigh harms and so breast screening should continue unchanged. Others disagree, and, notwithstanding the use of deliberative democratic methods to help ascertain public opinion, many writers are suggesting that breast screening programs should be more tailored to individual risk profiles in order to facilitate a better benefit to harm ratio. For example, that those at higher risk of dying from breast cancer, for whom benefits of screening are likely to be greater, should have more screening than those who are at lower risk of dying from breast cancer and are therefore less likely to benefit from screening. Tailored screening programs are discussed in greater detail in Challenges and Opportunities in the Implementation of Risk-Based Screening for Breast Cancer, Breast Cancer Screening in the Older Woman, Screening Women in Their Forties, Screening for Breast Cancer in Women with Dense Breasts, Screening Women with Known or Suspected Cancer Gene Mutations, Imaging Surveillance of Women with a Personal History of Breast Cancer

Summary: delivering more benefits than harms

- ●

The benefit to harm ratio in breast screening is more closely balanced than previously thought.

- ●

Given the qualitative differences between benefits and harms, and variations in how much to prioritize the principles of maximizing benefits and minimizing harms, it is hard to know where, exactly, the balance between breast screening benefits and harms lies.

- ●

Involving consumers at the levels of policymaking and individual decision-making may assist with making this calculation.

Delivering the Most Benefit Possible Within the Resources Available

Given that resources for healthcare are always finite, resource allocation and the amount of benefit received for a given investment is worthy of ethical consideration. In the context of breast screening it is relevant to not only explore how much benefit can be delivered while minimizing harms, but also how to maximize the benefits that matter within a healthcare budget .

Population breast screening is an expensive program, even when taking into account healthcare savings associated with earlier diagnosis and treatment, and containment of costs that might otherwise accrue from unregulated, opportunistic screening. The high cost of breast screening programs does not mean they should not be funded, but it does mean there are opportunity costs to other potential areas of expenditure, and we should consider how breast screening costs compare with other healthcare expenses. There is controversy over this, partly due to lack of consensus over mortality benefit and overdiagnosis figures. We should also consider ways to keep breast screening as cost-efficient as possible. Attaining and maintaining a high level of public participation is often suggested as being important for cost-efficiency but this is contestable. For many screening programs, the main expenses are the variable (participant related) costs associated with actually performing the screens and follow up tests, rather than the fixed (setup and infra-structure) costs, and as such, screening can be cost-effective even with low rates of participation. Given this, the common link made from cost-effectiveness to participation rates may be less certain than is sometimes suggested.

Summary: the most benefits within resources

- ●

Cost-effectiveness of breast screening compared to other healthcare expenditure is controversial.

- ●

For cancer screening generally, it is not clear that high participation rates are required to achieve cost effectiveness.

Respecting and Supporting Autonomy

Respecting, or supporting, the autonomy of individual patients, consumers, or citizens is a fundamental principle in healthcare ethics. For the purposes of this discussion, we regard an autonomous person as one who: sees herself as in being charge of her own life; believes this to be appropriate; and has the freedom, opportunity, skills and capacities required to make choices, take action, and live in a manner that is consistent with her sense of who she is. Being autonomous thus relies not just on the person herself, but also the people, systems, and society that surround her. These relationships and systems can either support or diminish her autonomy.

Informed decision-making in breast screening

The facilitation of informed decision-making in breast screening is an important part of supporting and respecting autonomy. Many writers have expressed concern that breast screening communication with consumers should: (1) include evidence-based information about risks and benefits; and (2) be designed to inform women in a balanced way rather than persuade them to participate. Many countries have recently released or will shortly release new information pamphlets. We mentioned above that facilitating informed decision-making about breast screening may be more likely to produce beneficial outcomes. This may be for several reasons: for example, the experience of having one’s autonomy supported may increase one’s sense of wellbeing; also, if we believe that we are all best able to know our own interests, the choices we make for ourselves may be more likely to be beneficial to us. In this section, however, we present autonomy as something to be valued in its own right irrespective of the resulting consequences, and suggest that facilitating informed choice has independent value from whether or not it improves the benefit to harm ratio.

How else should we support and respect women’s autonomy in breast screening?

Providing opportunities for informed decision-making is only one part of supporting and respecting autonomy. Other aspects of respecting and supporting autonomy in the breast screening context include, for example:

- ●

Communication that indicates women have the authority to decide whether or not participation is right for them (rather than suggesting that they should not question participation, or are in no position to decide);

- ●

Ensuring that women understand the implications of participating or not participating in screening; and

- ●

Ensuring that women have an opportunity to consider screening in the context of their own values and sense of self.

How important is supporting and respecting autonomy?

Respecting autonomy is considered a very important concept in healthcare ethics. In the Four Principles approach within clinical ethics discussed earlier, respect for autonomy has been referred to as the “first among equals.” Writers on public health ethics have recently tended to criticize excessive importing of clinical ethics concerns, particularly respect for autonomy, into public health contexts, arguing that this potentially overrides community-orientated principles such as justice, solidarity, and reciprocity which are fundamental to public health practice. Certainly the extensive evidence that individual health is heavily influenced by social, as well as personal, factors suggests that it may be misguided to conceptualize respect for autonomy as independence of choice, or to prioritize this as a good.

The principle of respecting autonomy may conflict with other principles discussed here. For example, it may be very hard to engage large numbers of women in informed shared decision-making for a complex topic like breast screening, especially if they are not well-informed to begin with. Some writers argue that enabling all consumers to make their own, fully informed, choices about screening would be so resource-intensive and challenging that it would seriously undermine the cost-effectiveness of screening. Others disagree, arguing that informing women about breast screening is not especially difficult or that respecting autonomy should be such a high priority that we may be obliged to offer such information and support if breast screening is to continue, regardless of cost. Respecting autonomy may also influence the level of benefit delivered by screening. There has been concern that embarking upon an informed consent process for breast screening may worry consumers, and reduce public participation in breast screening programs. Despite this, varied stakeholders support the principle of respecting autonomy strongly enough that there is reasonably widespread international support for shared decision-making and informed choice in cancer screening.

Summary: respecting or supporting autonomy

- ●

Facilitating informed choice is an important aspect of respecting autonomy in breast screening.

- ●

There is disagreement over whether or not facilitating informed choice might be excessively expensive or decrease public participation rates, and over how to balance support and respect for autonomy against other ethical principles.

Honesty, Transparency, and Procedural Justice

Ethically justified and legitimate public health decisions and actions will generally have the qualities of honesty, integrity, and openness. This is relevant to the substance of communication, and the process of decision-making and implementation.

Ethically justified programs will pursue full and honest disclosure of information that might be considered relevant for consumer decision-making. Communicating honestly is, in part, a way to show respect for individuals and their autonomy as discussed above, but many would also regard it as being important in its own right. That is, many think that governments should, as a general rule, be open and up-front when communicating about their policies and programs. Transparency is the full and honest disclosure of how, and by whom, decisions and policies are made. This includes the disclosure of possible vested interests among policymakers and advisors in order to facilitate accountability and take account of possible bias. Procedural justice is about fairness in decision-making: for example, ensuring that all relevant stakeholders are included, that decisions are made for good reasons, that decisions are open to revision if new evidence or arguments emerge, and that the influence of biases and vested interests are minimized in order to ensure decisions are made in the best interests of the public.

Vested interests in breast screening

Communication with breast screening consumers is often produced by breast screening providers who are required to meet participation targets. Truthful communication about breast screening may be facilitated by changing the key performance indicators for breast screening services from rates of consumer participation in screening to rates of consumer understanding and participation in shared decision-making. It may also be preferable for information to be written by independent experts.

Breast screening policy decisions are often heavily influenced by government or independent experts who review existing evidence and issue comments or guidelines. As in any public health program, experts may have commercial, political, or professional interests in a particular outcome that may bias the policymaking process. Debates about vested professional interests are a particularly common topic in breast screening. The breast screening evidence is complex and contradictory and there have been many reviews of the multiple breast screening trials and studies that have presented variable conclusions regarding the benefits and harms associated with breast screening. There has been widespread and public accusation about vested interests of key expert clinicians and researchers with a long history of practice or publication related to breast screening who promote or criticize screening. The declaration of commercial interests is a widely accepted tradition, but some writers suggest the principle of transparency also demands that all professional interests should be declared (eg, the reputational interests of experts in continuing to defend a long-held position). Others advocate that procedural justice requires accepting only independent experts as advisors or decision-makers, excluding practicing clinicians and academics who have previously published on the topic, or to ensure that all legitimate stakeholders are involved in decision-making in order to reduce the chance of any one vested interest dominating the process.

Summary: honesty, transparency, and procedural justice

- ●

Breast screening communication and decision-making may be biased due to vested interests, including professional vested interests, in a particular outcome.

- ●

Honest communications about breast screening may be facilitated by strategies such as removing participation targets or using independent experts.

- ●

Those with professional vested interests could be asked to declare their interests, or be excluded from decision-making.

Distributive Justice

Distributive justice is about fairness: fairness of opportunity (eg, the opportunity for all individuals to pursue good health) and fairness of outcome (eg, everyone in a society achieving at least a basic or threshold level of good health). Achieving justice does not necessarily mean that everyone is treated equally: more effort may need to be expended on some individuals than others in order to attain the same opportunity for, or achievement of, good health. Thus, justice may demand that those with the more limited health opportunities or the poorest predicted health outcomes receive priority.

Justice in opportunity

The opportunity for women to attend breast screening remains an important issue. Several barriers to breast screening opportunities have been identified, including geographic, sociocultural, and financial. Many programs have sought to remove or ameliorate these barriers through actions such as: mobile breast screening services, culture- and language-specific consumer communication strategies, and reduced cost or free screening. These policies may be expensive, and may bring the principle of justice into conflict with other principles, such as delivering the most benefits within available resources.

Justice in health outcomes

Is breast screening a fair strategy in terms of population health outcomes? Certainly breast screening only benefits a minority of the population, but given that people with breast cancer are more likely to have poorer health outcomes, it would seem to be consistent with the principle of justice to expend effort on trying to improve this outcome. Some writers disagree: while breast cancer may affect any woman, it is more common among those with higher socioeconomic status—that is, women from the group who are, on average, more likely to have good health and opportunities to achieve it. It has been suggested that the breast cancer focus is discriminatory, and a fairer public health system would be one that targets the needs of people who have poorer health outcomes—for example, those with significant social disadvantages or physical disabilities. In this view a more just approach might be one that focuses less on early detection of breast cancer, and more on providing basic social and health infrastructure for all (eg, public transport, a healthy food supply, and affordable treatment services) as well as targeted programs to address the needs of those groups with the worst health outcomes. Notice, though, that this takes for granted that it is reasonable to trade these health-related goods off against one another within a limited health budget. It is likely that many high-income countries could afford both breast screening and interventions to reduce structural disadvantage if they reduced spending in other, arguably less important, policy areas.

Summary: distributive justice

- ●

Many breast screening programs have policies that aim to give all women fair opportunities to attend screening.

- ●

Some writers suggest breast screening makes a relatively small contribution toward the fairness of distribution of health outcomes.

Reciprocity

The principle of reciprocity is generally used to refer to concepts such as returning a favor that is done to us, sharing in carrying public burdens, and supporting and compensating those who carry the heaviest burdens.

Reciprocity, individuals, and breast screening

The principle of reciprocity would suggest that individuals who live in and therefore gain health benefits from a society that offers breast screening should be cognizant and supportive of these benefits. In particular, they should not act so as to reduce the opportunity for others to receive similar benefits. This may suggest certain limited obligations for women: for example, to actively attend, cancel, or reschedule appointments so as not to prevent or delay another woman from accessing the service. Whether there is any more substantial reciprocal obligation for women is arguable. We discussed possible corporate benefits of breast screening programs in a previous section (eg, improved breast cancer treatment). We argued that such benefits, which have already been achieved, are not clearly contingent on women’s continued participation. This suggests that individual women should not consider themselves obliged to participate in exchange for these existing corporate benefits. Some might suggest that the existence of a publically funded healthcare service is a benefit to all, and that in return, citizens should take reasonable care of their health, which includes attending screening services when advised to do so. It is now common in public health generally to emphasize the importance of individual behaviors, often framed in terms of individual responsibility and duty. This moral language can suggest some kind of reciprocal obligation on individuals. However many would reject this, arguing, for example, that breast screening is not a necessary way for a society to demonstrate its commitment to women’s health, so women do not have any reciprocal responsibility to participate (or not participate) in breast screening in particular.

Reciprocity is also relevant to breast screening as a driving force in screening advocacy. Individuals who have been diagnosed with illness through screening may feel they have benefited from that program and wish to return the good. Thus the concept of reciprocity may be invoked by screening consumers who seek to “give back” to society through involvement in activities related to screening promotion and advocacy. This is a sensitive issue, particularly if the positions of those advocates, often resolutely proscreening, seem to ignore more recent evidence about the uncertain balance between benefits and harms of screening. Despite this potential to distort the accuracy of communication, it seems important to recognize the moral value of these advocates’ desire to reciprocate, as this provides a stronger basis from which to engage respectfully.

Reciprocity, the state, healthcare systems, and breast screening

The principle of reciprocity requires that breast screening programs should seek to minimize disproportionate burdening of any one individual or group of individuals and should support and compensate those who carry burdens, particularly the heaviest burdens. For example when countries offer organized, publicly funded breast screening, the absence of a financial barrier could be seen as a reciprocal exchange to these women for their status as taxpayers and for their willingness to participate in a service that is unlikely to benefit them personally. Screening programs that include free follow-up testing to the point of diagnosis ensure that women who receive false-positive tests and thus already carry a disproportionately heavy burden of screening (associated with inevitably imperfect quality control) are not further burdened by financial costs. Privately operated breast screening, by contrast, may simply charge per item. This not only means that women must pay to participate, but also that women who receive false-positive screening tests due to limitations of mammography pay more for their screening event than other women. Part of the discomfort that we may feel about this arrangement is likely to be recognition that it contravenes the principle of reciprocity.

Summary: reciprocity

- ●

In a society that offers breast screening, women may be bound by the principle of reciprocity to at least consider screening, and to accept or cancel screening appointments.

- ●

Privately funded screening programs may contravene reciprocity by failing to ameliorate the disproportionate burdens of screening carried by those who receive false-positive tests.

Solidarity

Commitment to solidarity has been implicit in public health since its earliest origins, although explicit discussions of solidarity in public health ethics have emerged more recently. Solidarity is “pulling together” toward a common (collective) cause on the understanding that there is mutual respect and obligation between members of a community, and a sharing of burdens and threats. Readers might note some overlap between reciprocity and solidarity: both are grounded in ideas about mutual obligation and collective interests.

Solidarity expressed by individuals

Individuals may participate in breast screening for reasons of solidarity—that is, partly to contribute toward benefits for others. Karen Willis, for example, has shown empirically that women in rural Australia are motivated to visit mobile breast screening vans partly to show support for services that may be needed by others in the future. It is possible to recognize the moral value of this expression of solidarity, but question the reasoning that underpins it. In many cases, for example, lack of attendance should not necessarily threaten the viability or continuation of breast screening. Fine-tuning screening according to risk profile may over time decrease the perception that participation by low-risk women is a valuable expression of solidarity with high-risk women.

Uses of solidarity by the state (or by organized screening programs)

Solidarity may be used by the state to justify promotional activities aiming for high breast screening participation rates. That is, while it is recognized that screening will not benefit most people, and will be (mildly, moderately, or severely) inconvenient or harmful to many people, it may be acceptable that screening is promoted in order to maintain a politically and economically viable program that delivers large benefits to some.

While the concept of solidarity remains a strong driver for public policy, it is not clear how much burden many members of a society should be expected to shoulder in order to deliver benefit to a few. Some argue that the amount of societal burden attached to breast screening is large and the amount of benefit is small, and it is therefore unreasonable for the state to decide that the public should shoulder that burden. Others argue that the benefits are large and the burdens small, and therefore operating a breast screening program is entirely justifiable. It may be useful to explore community ideas about the importance of solidarity in the context of breast screening; this could be done, for example, by using a citizens’ jury to answer the question of whether or not the state is justified in asking people to shoulder the expected burdens of breast screening in order to deliver the predicted level of population benefit.

This way of looking at solidarity and breast screening views breast screening as a topic in isolation. An alternative way of looking at solidarity is to look more generally at population health or even population well-being. At this more holistic level, we might ask the question of how we, as a society, should pull together in order to facilitate well-being in others, and consider the impact of a particular policy, such as breast screening, on the flourishing of the community. This would require a holistic assessment of the extent and distribution of the benefits and burdens of breast screening in the context of other possible health-supporting programs, and deciding how best to recognize the importance of community interests and act for the well-being of each other.

Summary: solidarity

- ●

Individuals may attend, and states may promote, breast screening for reasons of solidarity: while solidarity in itself may have moral value, its use to promote breast screening deserves close scrutiny.

- ●

Prioritizing solidarity may require that we consider breast screening in the context of the broadest range of possible health-supporting programs and community interests.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree