Major Concepts

History

Infectious diseases have had a great impact on human history, killing vast numbers of persons and disabling or disfiguring many others. Some diseases have transformed the social and economic landscape of a region, as when the decline in the peasant population following the Black Death contributed to the end of the feudal system. The fight against smallpox led to the development of vaccination, a weapon in the human arsenal that prevented major loss of life by protecting people from a wide range of diseases. Due to an ever-better understanding of the causative agents of infectious diseases, other tools have been developed to prevent or treat illnesses, including improved sanitation, greater availability of clean drinking water, the increased use of disinfectants, the discovery of antimicrobial compounds, and improvements in the inspection, processing, and preparation of food and drink. The incidence and severity of infectious diseases have fallen in developed nations but are again on the rise worldwide.

Infectious Diseases Today

The leading causes of death due to infectious diseases in the world today are lower respiratory tract infections, diarrheal diseases, HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, malaria, and dengue hemorrhagic fever and shock syndrome. Many of the victims of these diseases belong to the most vulnerable segments of our population, the very young and the very old, those weakened by other pathological conditions, and those with compromised immune responses. Many other diseases affect smaller segments of humankind. Some of these preferentially strike those living in certain climates or ecosystems, in lower socioeconomic groups, or in regions of civil unrest and war. Other diseases are more prevalent in some racial groups, age ranges, occupations, or one gender. Still other diseases are indiscriminate killers. Incidence of some diseases peaks in certain seasons, while others occur year round.

Emerging and Reemerging Infectious Diseases

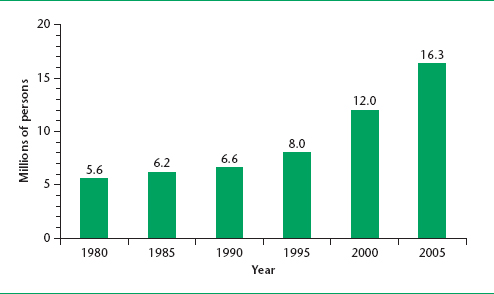

Many diseases have either been described for the first time within the past 40 to 50 years or have increased in incidence, severity, or geographical range. This text focuses on a number of such diseases and the associated microbes. Several factors in combination have contributed to the explosion of emerging and reemerging infectious diseases in recent times (as evidenced by the Timeline at the end of this chapter). Our awareness of new infections may be due in part to improved detection and understanding of the underlying causes of illness. Many of the emerging diseases, however, appear to be entirely new to humans, while many reemerging diseases represent increasing threats to humankind. Several of the factors believed to contribute to the emergence or reemergence of infectious diseases include microbial evolution, the trend toward increasing urbanization, population migrations between regions or into formerly uninhabited areas, the ease and speed of long-distance movement of persons and materials, natural disasters, climatic and ecological changes, and decreased vaccination rates in many regions of the world. One of the important factors contributing to the rapid emergence of new infections is the increasingly large numbers of immunocompromised individuals who are vulnerable to the development of severe or life-threatening diseases as a result of infection by organisms formerly viewed as nonpathogenic.

History of Infectious Diseases

Much of the history of humankind has been critically shaped by infectious diseases. Large, widespread outbreaks of bubonic, pneumonic, and septicemic plague, caused by infection with Yersinia pestis, have struck repeatedly, including the Plague of Justinian from 542 to 767, which killed 40 million people in Europe and Asia Minor and initiated the Dark Ages, and the Black Death, lasting from the fourteenth to eighteenth centuries. The latter began in Central Asia and subsequently spread to China, India, and Asia Minor, entering Italy in 1347. Twenty-five to fifty percent of the population of Europe succumbed to the plague within the next three years, leading to the death of many peasants and the abandonment of much of the agricultural land. The resulting food shortage and loss of an abundant workforce rendered the existing governments ineffective. These were major factors in the eventual collapse of the feudal system and the rise of middle-class artisans. Improvements in sanitation were also implemented due to lessons learned during the plague years.

Smallpox is another disease that changed the face of human history, quite literally, for over three thousand years, afflicting humans with horrific and disfiguring scars, blindness, and death for most of our known existence. Its eradication has been one of our greatest achievements.

The rich and powerful were not spared the attention of this deadly pestilence. Scars were even found on the mummy of the Egyptian pharaoh Ramses V. Throughout the ages, the fatality rate often approached 30%, with 65% to 80% of the survivors left with pockmarks on their faces as reminders of their ordeal. As late as the 1700s, 10% to 14% of the children in France, Sweden, and Russia died of smallpox. Surviving the disease was almost a rite of passage, and no parent could be totally at ease until his or her children had vanquished that most dreaded foe.

“The smallpox was always present,” wrote T. B. Macaulay, “filling the churchyards with corpses, tormenting with constant fears all whom it had stricken, leaving on those whose lives it spared the hideous traces of its power, turning the babe into a changeling at which the mother shuddered, and making the eyes and cheeks of the betrothed maiden objects of horror to the lover.”

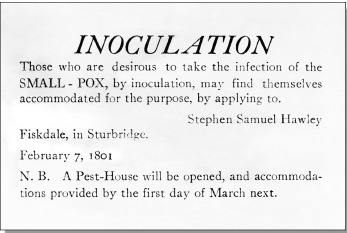

It was observed in China over a thousand years ago that survivors of smallpox did not contract the disease again, even after extended exposure to infected persons. It was additionally discovered that inoculation of previously unexposed persons with material from dried smallpox scabs derived from persons with mild cases of the disease often safeguarded the inoculated persons against developing severe infection at a later time. This practice was known as variolation and occasionally resulted in death. Variolation was brought to Europe in 1721 by Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, the wife of the British ambassador to Turkey. Decades later, Edward Jenner acted on the common observation that milkmaids, who typically developed the mild disease cowpox, did not later suffer from smallpox or develop the hideous scars present on most members of society. In 1796, he modified the practice of variolation by inoculating a young boy, James Phipps, with material from cowpox scabs and subsequently challenging him with smallpox. Fortunately for James (and humanity), the boy was protected.

Thus began the age of vaccination, which ultimately led to the eradication of smallpox as a result of the concerted efforts of many dedicated individuals working under difficult conditions throughout the world for a decade. The program featured the quarantine of patients and their contacts as well as vaccination of all potential contacts. Ali Maalin from Somalia is believed to have acquired the last naturally occurring case of smallpox in 1977. Several subsequent cases occurred several years later in England following viral escape from a laboratory.

While smallpox remains the only disease that humans have totally eliminated from nature, the lessons learned during this triumph of humans over one of its most deadly foes have been applied many times in subsequent years. Highly effective vaccines have been developed and brought into widespread use to tame other serious microbial diseases such as polio, whooping cough, German measles, mumps, and tetanus. The science of epidemiology, initiated by John Snow to trace the source of a cholera epidemic in London in the 1850s to a specific water pump, transformed public health. The “germ theory of disease,” developed by Louis Pasteur, Robert Koch, John Lister, and others in the 1860s, revolutionized beliefs concerning the origins of diseases. These developments—along with improvements in sanitation, the availability of clean drinking water, practices such as pasteurization and sterilization of beverages and food, increased use of disinfectants, the discovery of antimicrobial compounds such as antibiotics (discussed in Chapter Eleven) and antiviral drugs, improvement in the inspection of meat and processing facilities, more thorough cooking of meat and eggs, and educational programs—eventually served as tipping points for many infectious diseases in the developed areas of the world. The numbers of cases of microbial illnesses dramatically declined: the incidence of tuberculosis, malaria, cholera, and many other diseases fell either regionally or around the world. Many persons in the public health arena in the early 1970s declared an imminent end to threats by infectious diseases.

The victory dance proved premature. A number of factors reversed the gains made in humankind’s war against pathogenic microbes. Diseases thought to be on the brink of extinction reemerged with a vengeance, and many new devastating diseases, including AIDS and a variety of hemorrhagic fevers, began to appear at an alarming rate. Rather than an end to the war against microbes, we were surprised to find ourselves facing fresh troops and new enemies. The battle continues as both sides reassess their strategies and struggle to develop new weapons better suited to the continuingly evolving situation.

The Role of Infectious Diseases in the World Today

A number of serious infectious diseases affect humans currently. The type of microbe, the mode of transmission, and the incidence of disease within a population or region varies according to income levels and socioeconomic status, age, gender, type of employment, general health parameters, social customs, housing preferences, climate and ecology of the region (temperature and rainfall; woodland versus prairie versus coastline), and the types and abundance of vector and reservoir species. Many of the diseases strike primarily members of the population with poor immune responses: the very young, the elderly, pregnant women, and immunocompromised individuals. Some infectious diseases, including Lyme disease and hantavirus pulmonary syndrome, preferentially strike men and women between the ages of 20 and 40. Other serious illnesses, such as pandemic influenza, are more indiscriminate with regard to their victims’ age. Due to differences in occupational exposure and recreational activity, some infectious diseases, among them the American hemorrhagic fevers and ehrlichiosis, strike men more frequently than women because males are more likely to spend time working in the cornfields and on cattle ranges or hunting and fishing in the wooded areas where the rodent or insect vectors of these diseases are found. Others are more common among women. One such example is the prion disease kuru, which afflicted women exposed to prions while preparing brains for consumption during funeral rites. Persons in poor overall health are more likely to succumb to infectious diseases. Once infected with one microorganism, individuals are more susceptible to other infections due to generalized immunosuppression. Social customs may increase infectious disease incidence as exemplified by funeral rites that exposed women to the Ebola virus. The type of housing common to a given region also affects disease incidence. People living in homes with thatched roofs and no screened windows or doors are exposed to disease vectors, as seen with Chagas’ disease in South America, where the “kissing bug” vector bites humans sleeping in the thatched huts at night. Tropical areas are home to many, but not all, of the emerging infections presented in this book. A hot, humid environment may support large populations of insect vectors year round. Some microbes are unable to survive in colder environments. Vector and reservoir species availability also influences the spread of diseases. Chagas’ disease is moving into parts of the southern United States, where the insect vector can survive the winters and where abundant small mammals are present to serve as reservoir hosts.

The population of immunosuppressed individuals in both developed and developing regions is increasing, leading to the emergence or reemergence of many infectious diseases. The AIDS pandemic has been responsible for much of this increase, especially in developing regions. Organisms other than HIV, such as Epstein-Barr virus (causative agent of mononucleosis) and herpesviruses, suppress immune reactivity. The aging of the population in developed regions is also a factor because various immune system components either decrease in mass (thymus), numbers (some populations of T lymphocytes), or effectiveness (T and B lymphocytes, natural killer cells) as persons age. Diabetes and cancer chemotherapy also compromise immune response. The incidence of both diabetes and cancer is increasing in developed nations due to obesity and recent alterations in diet, exercise, lifestyle, and occupation.

Depression also adversely affects various aspects of the immune response because functions of the central nervous system and the immune system are closely linked. Anti-inflammatory medications that are used to treat autoimmune disorders, such as rheumatoid arthritis, Crohn’s disease, psoriasis, and systemic lupus erythematosus (such as corticosteroids), suppress lymphocyte responses and increase susceptibility to infectious diseases, such as tuberculosis and staphylococcal infections.

Several infectious diseases cause a great degree of suffering and death in the world today. Lower respiratory tract infections are caused by several bacteria, viruses, and protozoa, including Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenza, respiratory syncytia virus, influenza viruses, parainfluenza viruses, and Pneumocysitis jiroveci (formerly P. carinii). These together constitute the leading cause of death due to infectious disease. Diarrheal diseases are the second leading infectious cause of death throughout the world and are the primary cause of malnutrition. Diarrheal organisms include Vibrio cholerae, Shigella spp., Campylobacter spp., Salmonella spp., rotavirus, Cryptosporidium spp., E. coli, and Giardia lamblia. Children under the age of 2 years are most vulnerable to these infections, and 1.5 million children die annually of diarrheal disease. HIV/AIDS is the single leading infectious cause of death. In 2007, some 33 million persons were living with HIV, and 2.7 million new infections were recorded. Approximately 2 million HIV-related deaths occur each year, and 25 million persons have died from AIDS since the mid-1980s. The tuberculosis bacterium infects about one-third of the world’s population and killed almost 1.6 million people in 2007. Many people are coinfected with HIV and M. tuberculosis: indeed, tuberculosis is one of the leading causes of death in HIV-positive persons. Malaria caused around 1 million deaths in 2005, and 247 million persons were infected with the parasite responsible. Very young African children are especially vulnerable to infection and death and average 1.6 to 5.4 episodes of malarial fever per year. We are currently in the midst of a pandemic caused by the dengue virus, resulting in the extremely painful dengue fever (“breakbone fever”) or the very dangerous dengue hemorrhagic fever, which has a high fatality rate if untreated. Fifty-six million infections occur each year, and the number of cases and disease range are increasing, with explosive outbreaks being reported.

The Links Between Infectious Diseases, Poverty, and Civil Unrest

Infectious diseases continue to be major causes of human death in the world. This is particularly true for areas that are gripped by poverty and the associated ills of decreased access to clean drinking water, malnutrition, overcrowding, substandard housing that does not fully protect against physical or biological threats (temperature extremes, wetness or dryness, insects, and rodents), inadequate health care, and poor educational opportunities. These factors combine to undermine the health of infants, children, and adults in the affected regions, leaving them vulnerable to infectious illnesses. Exposure to insect and rodent vectors in the home increases the spread of pathogenic microbes responsible for diseases such as bubonic plague, malaria, yellow fever, and Lassa fever. Contaminated water supplies transmit diseases such as cholera and schistosomiasis. Overcrowded living conditions, such those found in the slums of major urban centers, homeless shelters, and some prisons, nursing homes, and mental health facilities, permit the rapid spread of infections such as tuberculosis and typhus. Women may be forced into prostitution to obtain money for food for themselves and their children, increasing their risk of acquiring sexually transmitted diseases such as AIDS and syphilis. Children born of infected mothers may become infected in utero, during labor, or via contaminated breast milk. Persons addicted to drugs or alcohol may live in poverty or turn to prostitution in order to obtain funds to feed their habit.

Once individuals in a poverty-stricken region have acquired an infectious disease, they are unlikely to receive adequate treatment due to the inability to pay for services and medications or the lack of health care facilities and practitioners in close proximity to their residence. Many impoverished regions are located in remote areas with few roads. Most of the population may not own a motor vehicle to allow travel to distant sites, and fuel may be either too expensive or too scarce to permit its use by the majority of persons. Roads may be in poor condition or impassable during the wet season. Many governments may be unable or unwilling to provide basic health services or emergency care. Educational programs that could reduce disease incidence or severity are often of limited value because much of the population may not own televisions or radios and may not read newspapers due to illiteracy.

Poverty and disease often form a vicious circle that entraps large regions of the world today. As noted, poverty may set the stage for sickness. Sickness may then deepen the poverty of an area as individuals who could have been vital members of the workforce, producing food and bringing money into the region, are too ill to be fully productive or to work at all. Corporations may be unwilling to bring factories into regions with ill workers. Areas of sub-Saharan Africa suffer from decreased tourism as travelers hesitate to expose themselves to tropical diseases, some of which are difficult to prevent or treat. Ill children may have frequent absences from school. Some infectious diseases impede children’s physical and cognitive development, interfering with their ability to learn the information and skills necessary to lead themselves and their societies out of the grip of poverty and increasing the distance between developed and developing regions of the world.

Many regions of the world suffer under the twin burdens of poverty and civil unrest. Civil wars as well as wars between nations force mass population movements. Combatants and refugees carry diseases from an indigenous region to other areas. Agricultural activity and economic development are challenged. Refugee camps may be hotbeds of infectious disease due to overcrowding, inadequate clean water supplies, lack of proper sanitation facilities, and malnutrition. Areas of active combat are barriers to transportation of food, medicine, and vaccines, not only to the involved area but also to areas served by the associated roads or waterways. Civil unrest and wars disrupt the fabric of society and may tear apart the social mores of the culture. This may further the spread of disease as sexual practices change in manners conducive to microbial transmission.

The role of infectious disease in the world today is linked to a region’s income level. In the world as a whole, coronary heart disease and stroke and cerebrovascular disease were the leading causes of death, responsible for 12.2% and 9.7% of the deaths, respectively, in 2004, according to the World Health Organization. Four of the remaining ten leading causes of death in the world are due to infectious diseases (lower respiratory tract infections, 7.1%; diarrheal diseases, 3.7%; HIV/AIDS, 3.5%; and tuberculosis, 2.5%; total, 16.8%). Among low-income countries, six of the ten leading causes of death were infectious diseases (lower respiratory tract infections, 11.2%; diarrheal diseases, 6.9%; HIV/AIDS, 5.7%; tuberculosis, 3.5%; neonatal infections, 3.4%; and malaria, 3.3%; total, 34.0%). In middle-income countries, on the other hand, two of the ten major causes of death were of an infectious nature (lower respiratory tract infections, 3.8%, and tuberculosis, 2.2%). Among high-income countries, only one of the ten leading causes of death in 2004 was an infectious disease (lower respiratory tract infections, 3.8%). Less than 25% of the people in low income countries live to the age of 70 years, and more than one-third of the deaths are among individuals under the age of 14 years. In middle-income countries, almost 50% of the population dies after the age of 70, and that figure exceeds 67% in high-income countries. The proportion of deaths among those under the age of 14 years is 10% and 1% in middle- and high-income countries, respectively.

Emerging and Reemerging Infectious Diseases

No one textbook can cover the vast numbers of emerging and reemerging infectious diseases that have either been discovered during the past four to five decades or have greatly increased in incidence or virulence regionally or worldwide during that time. A number of these have been selected for inclusion in this book. These include viral, bacterial, and protozoan infections and a number of important diseases found in both tropical and temperate and both developed and developing regions of the world. Some of these are familiar to the general public, while others are virtually unknown even to most members of the medical community in the developed world. The sheer number of new infectious organisms and their spread to novel geographical regions complicates the tasks of physicians, nurses, public health agencies, epidemiologists, and legislators in their roles of safeguarding the general population against infection. This text attempts to draw attention to a subset of these diseases, some of which were once as obscure and remote as slim disease in Africa was to health care personnel before the recognition of the AIDS pandemic. The health and lives of billions of people in the future relies on vigilance of health workers to trends in old diseases and to the emergence of others.

The following diseases are presented in this book:

Diseases Found Primarily in the Americas

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree