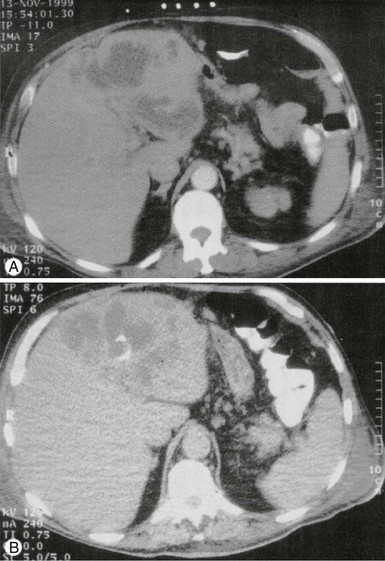

Costi D. Sifri, Lawrence C. Madoff Liver abscesses fall broadly into two categories: amebic and pyogenic. Amebic liver abscess represents a distinct clinical entity caused by invasive Entamoeba histolytica infection. It has a distinct pathogenesis that is characterized by the specific induction of hepatocyte apoptosis by the organism. Further discussions of the epidemiology, genetics, and biology of E. histolytica and of intestinal amebiasis can be found elsewhere in this volume (see Chapters 101 and 274). Pyogenic liver abscess, by contrast, does not represent a specific liver disease but is the end result of a number of pathologic processes that cause a suppurative infection of the liver parenchyma. In the United States, amebic liver abscess has become a rare disease that is found almost exclusively in travelers and immigrants. In 1994, the last year in which incidence data were collected, there were only 2983 cases of amebiasis; the percentage of cases complicated by abscess is unknown, but it is probably well under 10%, roughly 1 case per million persons per year.1 Worldwide, contamination of food and drinking water has maintained E. histolytica infection second only to malaria as a cause of death from parasitic disease. The epidemiology of this disease has been greatly informed by the appreciation that a closely related nonpathogenic species, Entamoeba dispar, colonizes between 5% and 25% of persons.2,3 E. dispar has no apparent propensity for invasive disease, even among patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). In industrialized countries, most asymptomatic individuals with Entamoeba in their stool are colonized with E. dispar, whereas in highly endemic regions, asymptomatic infection with E. histolytica may exceed the rate of E. dispar colonization.4,5,6–11 In addition, other Entamoeba species have been identified; these include Entamoeba moshkovskii, which causes noninvasive diarrhea, and Entamoeba bangladeshi, which is of unknown virulence. Because these species are indistinguishable by light microscopy, the presence of Entamoeba in the stool is not sufficient to establish the cause of a liver abscess. Men and women experience equivalent rates of E. histolytica infection, but adult men are at a 10-fold higher risk for invasive disease (colitis or extracolonic disease) than other populations.12 The reason for this disparity remains uncertain, although gender differences in complement-mediated killing of E. histolytica and cytokine responses to amebic liver infection have recently been proposed.13,14 In addition, testosterone has been shown to be a risk factor for the development of amebic liver abscesses in experimental animals.15,16 The incidence of pyogenic liver abscess is about 10 to 20 cases per 100,000 hospital admissions, or 11 cases per million persons per year.17,18 This incidence has been relatively stable, with a slight increasing trend in more recent case series that may reflect changes in the true incidence, improved detection, or changed admission practices. Pyogenic liver abscess is a disease of middle-aged persons, with a peak incidence in the fifth and sixth decades of life; this pattern mirrors the prevalence in the population of biliary disease, which is now the major cause of pyogenic liver abscess. No significant sex, ethnic, or geographic differences seem to exist in disease frequency, in contrast to the epidemiology of amebic liver abscess. About one half of patients have a solitary abscess. Right-sided abscesses are most common, followed by left-sided abscesses and then abscesses involving the caudate lobe. This distribution probably reflects the relative mass of each lobe, although more complicated explanations, such as patterns of hepatic blood flow, have been proposed. Infection with E. histolytica results from ingestion of cysts in fecally contaminated food or water. Excystation occurs in the intestinal lumen, and trophozoites migrate to the colon, where they adhere by means of a lectin that specifically binds galactose N-acetyl-D-galactosamine (the Gal/GalNAc lectin) on colonic epithelium and multiply by binary fission.19,20 At high densities, trophozoite encystation is initiated, and newly formed cysts are released into the stool to complete the life cycle. Most individuals experience asymptomatic infection, but approximately 10% develop symptomatic colitis when invasion of the colonic mucosa occurs. Spread to the liver via the portal system occurs in less than 1% of cases.2 A number of virulence factors have been implicated in the development of amebic liver abscess, including small proteins (amoebapores) that punch holes in lipid bilayers of target cells, cysteine proteases, and the Gal/GalNAc lectin.21–27 E. histolytica induces apoptosis in hepatocytes and neutrophils, forming large, nonpurulent, “anchovy paste” abscesses that grow inexorably without treatment.28,29 The mechanism by which E. histolytica induces apoptosis is unknown, but its importance is underscored by the resistance of caspase-3-deficient mice to amebic liver abscess formation.30,31 Recently, an E. histolytica surface protein that participates in apoptotic corpse phagocytosis, the phagosome-associated transmembrane kinase (PATMK), was shown to be required for intestinal amebiasis in a murine infection model; however, PATMK was found to not contribute to the development of experimental amebic liver abscess.32 By contrast, amoebapore expression was found to be required for the formation of liver abscesses but not amebic colitis.25 These findings suggest that the contribution of particular amebic virulence factors to pathogenesis may be tissue specific, and many of these factors have been recently reviewed.33 Predisposition to liver disease is influenced by host genetics. In studies of Mexican mestizo children and adults, individuals with the major histocompatibility complex haplotype HLA-DR3 have an increased frequency of amebic liver abscess compared with healthy populations of the same socioeconomic background.34,35 Host factors thought to be critical in the containment and clearance of invasive amebae include complement, neutrophils, interferon-γ (IFN-γ), nitric oxide, and adaptive immune responses (see Chapter 274).13,14,36–38,39,40 Pyogenic liver abscess does not represent a distinct pathophysiologic process but occurs whenever the initial inflammatory response fails to clear an infectious insult to the liver. Pyogenic liver abscesses are usually classified by presumed route of hepatic invasion: (1) biliary tree, (2) portal vein, (3) hepatic artery, (4) direct extension from contiguous focus of infection, and (5) penetrating trauma. Ideally, this approach defines the microbiology of the abscess and therefore guides empirical antibiotic choice, but it is limited by the high frequency of cryptogenic abscesses. The frequencies of the presumed routes of hepatic invasion are presented in Table 77-1.18,41–71 TABLE 77-1 Frequency of Route of Infection in Hepatic Abscess Host factors that predispose to abscess formation from “routine” hepatic bacterial insults may be present in many cryptogenic abscesses. Systemic illness such as diabetes mellitus, cardiopulmonary disease, malignancy, and cirrhosis are common in patients with liver abscesses and may be predisposing factors. Diabetes was shown in one retrospective study to impart a greater than threefold risk of development of pyogenic liver abscess.72 Moreover, neutrophil defects such as chronic granulomatous disease or Job’s syndrome are associated with a marked predisposition for abscesses of the liver and elsewhere.73 Finally, hemachromatosis conveys a particular susceptibility to abscesses caused by Yersinia enterocolitica.74 Although E. histolytica is the only species of Entamoeba known to cause invasive infections, certain strains may be more proficient at causing liver disease than others. In surveys of clinical E. histolytica isolates, genetically distinct strains recovered from amebic liver abscesses were infrequently found to cause asymptomatic intestinal colonization or intestinal disease.75,76 More recently, Ali and colleagues77 analyzed paired isolates from patients with concurrent amebic liver abscesses and intestinal infection. In all cases, the liver and intestinal amebae had discordant genotypes, suggesting that either amebae undergo genetic reorganization during invasion or that only a subset of strains is capable of metastasizing to the liver. In light of the diverse pathologic processes that have been discussed, it is understandable that sweeping generalizations about the microbiology of pyogenic liver abscess are difficult. The picture is further complicated because abscess material is rarely obtained before the administration of antibiotics. Even in the preantibiotic era, a high rate of sterile cultures was seen, probably reflecting inadequate culture techniques. Despite these difficulties, abscess cultures are positive in 80% to 90% of cases. The demonstration of anaerobic organisms in 45% of pyogenic liver abscess by Sabbaj and colleagues78 in 1972 led to an increased awareness of fastidious pathogens, and in recent case series, anaerobes were recovered 15% to 30% of the time.† Some of this decrease in the isolation of anaerobic organisms is probably attributable to the emergence of biliary tract disease as the major underlying cause of pyogenic liver abscess, but because of the difficulty in obtaining adequate culture data, these should be viewed as minimum estimates. There has also been an increased appreciation that many liver abscesses are polymicrobial, with estimates ranging from 20% to 50%, depending on the case series. If the source of the abscess is considered, abscesses with a biliary source are most likely to be polymicrobial, and cryptogenic abscesses are most frequently monomicrobial.57 Some observers have noted that solitary abscesses are more likely to be polymicrobial than are multiple ones.50,51 Although this has not been universally observed57 and the small size of these studies prevents conclusive statements, it does suggest two alternative mechanisms for abscess formation. In the first, a synergistic combination of organisms converges by chance to form a single abscess, and in the second, a highly pathogenic organism forms abscesses wherever it was seeded. In terms of specific pathogens (Table 77-2), Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae are by far the most common isolates. The latter has been increasingly recognized as a cause of community-acquired monomicrobial liver abscesses (discussion later). Enterococci and viridans streptococci are also common, primarily in polymicrobial abscesses. Staphylococcus aureus, by contrast, is more commonly associated with monomicrobial abscesses. Although pyogenic liver abscesses due to fungi, particularly Candida species, have been reported, they are comparatively rare and are excluded from most case series. In the mid-1980s, investigators in Taiwan first noted a distinctive syndrome of monomicrobial K. pneumoniae pyogenic liver abscess in individuals who were often diabetic but had no biliary tract disorders.79–81 Subsequently, community-acquired K. pneumoniae liver abscess has become a major health problem in parts of Asia, accounting for 80% of all cases of pyogenic liver abscess in Taiwan and South Korea,82–84 and has been reported sporadically elsewhere in Asia, North America, Europe, and Australia.85–88 Although mortality rates for epidemic K. pneumoniae liver abscess are generally low, metastatic infections such as meningitis and endophthalmitis occur in 10% to 16% of all cases.89–91 Not surprisingly, K. pneumoniae has also become a frequent cause of pylephlebitis in this region.92 Infections are primarily caused by hypermucoid strains of K. pneumoniae of the capsular K1 (or occasionally K2) serotype.89,90 Chuang and colleagues93 have identified a 25-kb chromosomal element containing 20 open reading frames that directs K1 capsular polysaccharide synthesis (CPS). Mutagenesis of one cps gene, magA (for mucoviscosity-associated gene A), abolishes hypermucoviscosity, increases sensitivity to phagocytosis and serum-mediated lysis, and reduces virulence in mice.94 magA can also be used as a genetic marker for invasive serotype K1 K. pneumoniae strains. Isolates are characteristically highly drug sensitive, but a recent case of community-acquired liver abscess caused by an extended-spectrum β-lactamase-containing strain of K. pneumoniae K1 and the spread of carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella worldwide raise the specter of highly drug-resistant, community-acquired disease.95 Patients with amebic liver abscess typically present with fever and a dull, aching pain localizing to the right upper quadrant, but jaundice is rare. Only 15% to 35% of patients present with concurrent gastrointestinal symptoms, including nausea, vomiting, abdominal cramping, or diarrhea (Table 77-3).18,42–45,46–71,96,97–103 Symptoms are acute (<2 weeks’ duration) in about two thirds of cases but can develop months to years after travel to an endemic area.2,3 The presentation is indistinguishable from pyogenic liver abscess on clinical grounds, and a careful search for epidemiologic risk factors is of paramount importance. Corticosteroid use and male sex are well-established risk factors for invasive amebic disease.12,96 TABLE 77-3 Signs and Symptoms of Liver Abscess Only 1 patient in 10 presents with the classic triad of fever, jaundice, and right upper quadrant tenderness. Fever is common, often without localizing signs but only with a general failure to thrive, including malaise, fatigue, anorexia, or weight loss (see Table 77-3). When present, localizing symptoms such as vomiting or abdominal pain are not specific. The duration of symptoms before presentation varied widely in most case series, and there was seldom agreement on an average duration. Butler and McCarthy44 attempted to address this issue by stratifying according to acute and chronic presentations. They found the former to be typically associated with acute, identifiable abdominal pathology such as cholangitis or appendicitis, whereas abscesses that presented chronically were often cryptogenic. Other series support an association between etiology and chronicity. For example, Seeto and Rockey57 found that hematogenous liver abscesses presented most acutely (3 days), and those secondary to pylephlebitis had the longest duration of symptoms (42 days). The diagnosis of liver abscess should be suspected in all patients with fever, leukocytosis, and a space-occupying liver lesion. Because of the nonspecific symptoms on presentation, the initial clinical impression is frequently wrong and may include cholangitis, pneumonia, hepatic malignancy, intra-abdominal catastrophe, or pneumonia.46 Before the widespread use of noninvasive imaging, liver abscess was among the most frequently identifiable causes of fever of unknown origin. Leukocytosis is present in most patients; recent studies65,66,69–72 report leukocytosis in 68% to 88% of all patients, with mean white blood cell counts of 15,000 to 17,000/mm3. An elevated alkaline phosphatase concentration is the most frequently abnormal liver function test, occurring in about two thirds of patients with liver abscess, but a normal value does not exclude the diagnosis. Abnormalities of alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and bilirubin are generally small, although they may be more pronounced in some patients with biliary disease. Albumin concentration and prothrombin time tend to be normal or nearly so. Chest radiographs are abnormal about half of the time but are of no real value in making the diagnosis. Therefore, although laboratory studies may suggest liver abnormalities, they are of no use in making the diagnosis of pyogenic liver abscess, and a high index of suspicion is required if the diagnosis is to be made in a timely fashion. Laboratory abnormalities may be of prognostic significance, most likely as markers of comorbidities. A multivariate analysis of risk factors found that a hemoglobin concentration of less than 10 g/dL and a blood urea nitrogen (BUN) concentration greater than 28 mg/dL were independent predictors of mortality in patients found to have pyogenic liver abscess (odds ratios of 13 and 14, respectively).61 Once the diagnosis is suspected, radiographic imaging studies are essential to diagnose pyogenic liver abscess.62 Ultrasonography and computed tomography (CT) scanning have proved particularly useful for demonstration and drainage of abscesses. Ultrasonography is the study of choice in patients with suspected biliary disease and in those who must avoid intravenous contrast or radiation exposure; it has a sensitivity of 70% to 90%. Contrast-enhanced CT scanning has improved sensitivity (≈95%) and is superior for guiding complex drainage procedures. Intravenous contrast is required for optimal imaging in two thirds of patients.104 Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies are seldom required, but they may be better at distinguishing abscesses from noninfectious liver lesions such as neoplasia. Fine-needle aspiration is the definitive diagnostic procedure, and MRI is a cumbersome tool for guiding drainage procedures. In patients with pyogenic liver abscess, blood cultures are positive about half of the time. It is imperative that multiple sets of anaerobic and aerobic cultures be obtained because these are frequently the only cultures obtained before antibiotic administration, and in about 7% of cases they are the only positive culture data obtained.50,57,69 The diagnosis ultimately rests on obtaining purulent material from an aspiration of the abscess cavity, usually under radiographic guidance. Failure to obtain the expected pus should prompt a reevaluation of the differential diagnosis, considering liver cyst, malignancy, and amebic liver abscess. Purulent material should always be sent for Gram stain, which may provide the only clue to a mixed infection in patients heavily treated with antibiotics. The importance of prompt delivery of anaerobic specimens under proper conditions cannot be stressed enough. Patients with amebic liver abscess classically present with a single large abscess in the right lobe of the liver, but the abscess can be anywhere and multiple lesions are not infrequent. Moreover, there is near-complete overlap in the symptomatology of the two diseases (see Table 77-3). A recent study from Spain showed that age 45 or younger, presence of diarrhea, and a solitary right lobar abscess favored amebic etiology.105 Distinguishing amebic from pyogenic liver abscess is not possible with the use of clinical criteria alone; however, a presumptive diagnosis of amebic liver abscess can be made in a patient with positive serology and a space-occupying liver lesion on CT or ultrasonography. Amebic serology (antiamebic antibodies) has a sensitivity of about 95% and is highly specific for E. histolytica infection. Although the test can be negative in a minority of acute presentations (symptom duration <2 weeks), a repeat serology determination is usually positive.106–109 It should be remembered that a positive serology result only confirms present or prior E. histolytica infection and cannot distinguish colitis from extraintestinal disease. Antigen detection represents a complementary diagnostic method. A commercially available ELISA assay that detects the Gal/GalNAc lectin has been shown to be positive in more than 95% of serum samples and about 40% of stool or abscess specimens in patients with amebic liver abscess.110 Several other U.S. Food and Drug Administration–approved ELISA antigen detection assays are also available, but some may cross-react with E. dispar.111,112 Microscopic examination of the stool for cysts is of little value because E. histolytica cannot be distinguished from E. dispar. Examination of aspirated liver abscess pus is also not recommended, given that trophozoites are identified in only 11% to 25% of cases.110,113 Nucleic acid amplification methods are promising diagnostic tools for invasive amebiasis and amebic liver abscess, but their use is currently limited to research laboratories.112,114–116 Some investigators have argued that in areas of low endemicity, suspected amebic liver abscess should be aspirated to exclude pyogenic liver abscess. Certainly, if there is no response to initial therapy, the abscess should be aspirated to confirm the diagnosis and to exclude pyogenic liver abscess. Bacterial superinfection of amebic liver abscess has been described in about 1% to 5% of cases, frequently as a complication of drainage procedures.117 Echinococcal cysts of the liver, which typically do not cause fever or tenderness, are distinguishable from amebic and pyogenic abscesses by CT but require separate consideration for aspiration (see Chapter 291). Amebic liver abscess can almost always be treated with medical therapy alone. Metronidazole (750 mg three times daily) is typically given for 7 to 10 days.2,3 An alternative, tinidazole (2 g daily for 3 days), has been used extensively in Europe and the developing world and has been approved for use in the United States for the treatment of amebiasis.118 Other nitroimidazoles with extended half-lives that are efficacious but not currently available in the United States include secnidazole and ornidazole. Decreased fever and abdominal pain are usually observed within 3 to 5 days after initiation of therapy. Patients frequently remain colonized with E. histolytica despite nitroimidazole treatment and should be treated with paromomycin, a nonabsorbable aminoglycoside with E. histolytica activity to eliminate this condition. It is generally accepted that uncomplicated amebic liver abscess does not require drainage. Percutaneous image-guided aspiration has replaced surgical drainage and should be employed if there is no response to appropriate therapy or the diagnosis is uncertain, to exclude pyogenic liver abscess and bacterial superinfection. Drainage should also be considered for large lesions at risk for rupture, particularly left-sided abscesses that can rupture into the pericardium. Percutaneous drainage has not been demonstrated to shorten hospital stay or to hasten clinical improvement, with the exception of one randomized controlled trial that found a salutary effect in patients with large abscesses (>300 mL).97,119–124 Unlike amebic liver abscess, pyogenic liver abscesses usually require drainage in addition to antibiotic therapy. Surgical drainage was traditionally the treatment of choice and, in the preantibiotic era, the only hope for cure. As early as 1953, McFadzean and associates125 reported the use of percutaneous drainage with antibiotic therapy to treat 14 patients with liver abscess. After ultrasonography and CT became widely available, multiple studies confirmed this approach and made image-guided drainage procedures the preferred primary therapy, although some still advocate surgical drainage (Fig. 77-1). Surgical intervention should be considered if percutaneous drainage fails or management of concurrent intra-abdominal disease is required, and also for some patients with multiple large or loculated abscesses.126,127 Percutaneous catheter drainage is successful in 69% to 90% of cases; the procedure is generally well tolerated and usually can be performed at the time of radiographic diagnosis.56,57,58,60,128 Aspirated material should be sent for Gram stain and cultured for aerobic and anaerobic bacteria. Meticulous handling of the specimen and rapid transportation to a qualified laboratory are essential for efficient recovery of anaerobes. Histopathologic biopsy specimens should also be obtained if possible. Depending on host and epidemiologic factors, microbiologic evaluation for fungi, mycobacteria, and E. histolytica should be considered. The catheter is usually left in place until drainage becomes minimal, typically 5 to 7 days. Percutaneous aspiration without catheter placement has received recent attention, with several studies reporting success rates between 58% and 88% for solitary abscesses 5 cm or smaller in diameter, similar to those observed with catheter placement.57,58,60,129–131 Success rates of 94% to 98% were reported in two studies in which percutaneous aspiration without catheter placement was followed by close clinical monitoring and serial ultrasound studies as indicated. Both investigations found that reaspiration was required in about 50% of cases, and a minority of patients required three or more aspiration procedures.132,133 Therefore, catheter placement may not be required in some patients, but prospective randomized control trials are necessary to clarify the role of aspiration alone versus catheter placement in the management of hepatic abscess.

Infections of the Liver and Biliary System (Liver Abscess, Cholangitis, Cholecystitis)

Liver Abscess

Epidemiology/Etiology

Amebic Liver Abscess

Pyogenic Liver Abscess

Pathogenesis and Pathophysiology

Amebic Liver Abscess

Pyogenic Liver Abscess

ROUTE OF INFECTION

FREQUENCY (%)

Biliary tree

40-50

Hepatic artery

5-10

Portal vein

5-15

Direct extension

5-10

Trauma

0-5

Cryptogenic

20-40

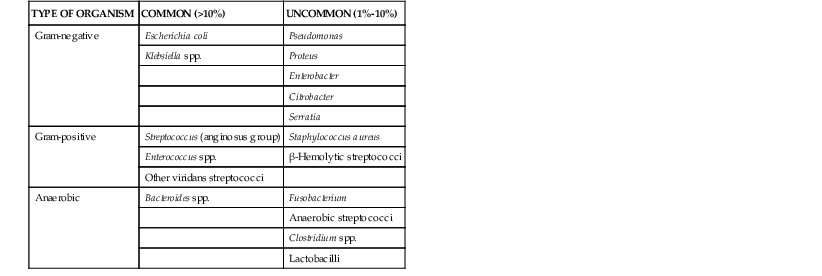

Microbiology

Amebic Liver Abscess

Pyogenic Liver Abscess

Epidemic Klebsiella pneumoniae Pyogenic Liver Abscess

Clinical Manifestations

Amebic Liver Abscess

FEATURE

AMEBIC LIVER ABSCESS16,42–45,46–71,105

PYOGENIC LIVER ABSCESS68,96,97–103

Epidemiology

Male-to-female ratio

5-18

1-2.4

Age (yr)

30-40

50-60

Duration (days)

<14 (≈75% of cases)

5-26

Mortality (%)

10-25

0-5

Symptoms and Signs (approximate % of cases)

Fever

80

80

Weight loss

40

30

Abdominal pain

80

55

Diarrhea

15-35

10-20

Cough

10

5-10

Jaundice

10-15

10-25

Right upper quadrant tenderness

75

25-55

Laboratory Tests (approximate % of cases)

Leukocytosis

80

75

Elevated alkaline phosphatase

80

65

Solitary lesion

70

70

Pyogenic Liver Abscess

Diagnosis

Therapy

Amebic Liver Abscess

Pyogenic Liver Abscess