Introduction

Throughout most of history, medical care was delivered to an individual patient by an individual clinician. Public health services were rarely available and infection control practices were poorly understood. Institutional care was uncommon and reserved for those with means to afford the medical services. Over the last century, medical care has drastically changed through the development of antibiotics, immunizations, and new surgical techniques. The world’s population is now growing rapidly, is ageing, and is requiring more health services. Population-based medicine has become a priority as cost, volume and efficiency became critical issues in meeting the growing healthcare demands of the medical consumer.

From provision of services to meeting standards of practice, the healthcare industry is under increasing pressure to provide the highest level of services to the greatest number of recipients. In an era of limited healthcare dollars, practitioners often must do more with less, yet medical advances and fear of litigation drive the cost of care upward. For these reasons, efficient, high-quality care is of increasing importance. Consumer groups, medical societies and healthcare organizations have been at the forefront in promoting quality in healthcare. With a collective voice, these groups have promoted change in the healthcare system. Although slower than many other industries, the healthcare establishment has recognized the importance of delivering quality goods and services.

With the advent of computers, the growth of the pharmaceutical industry, and advances in diagnostic technologies, the level of medical sophistication has risen dramatically. Clinicians and patients are now afforded a multitude of therapeutic options unavailable only a few years before. As with other industries, however, quantity of services does not automatically equate to quality of services. It is necessary to critically evaluate not only medical treatments and techniques but also the process by which medicine is delivered to the healthcare consumer. Defining quality, measuring performance and changing ineffective practices must now become routine activities as medicine moves toward more efficient and effective methods of healthcare delivery.

The History of Quality

The History of Quality in Business

In 1906, the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) was established to provide uniformity to the electrotechnical field. (See Appendix 137.8 for organizational abbreviations.) The IEC promoted quality, safety, performance, reproducibility and environmental compatibility of materials and products. This was the first organization to develop international standards of business practice.

The International Federation of the National Standardizing Association (ISA) was another organization, focused on mechanical engineering, which set standards for industry and trade from 1926–1942. After ISA dissolved, a delegation of 25 countries convened to create a new organization to unify the standards of industry and production practices. In 1947 this organization, the International Organization for Standardization (ISO), was established in the United Kingdom to oversee the manufacturing and engineering trades.

The ISO is a federation of non-governmental agencies with membership from 163 countries across the world.1 The ISO has developed international standards by which trade, technology and scientific activities can be measured. Companies may choose to be certified by the ISO-9000 quality management system. This certification ensures a minimum standard by which business processes, quality management and safety are maintained.1 ISO certification is especially important for international and intercontinental business to ensure a uniform delivery of goods and services. The healthcare industry is one of many fields that may be evaluated in the ISO method. At this time ISO has developed 187 work item standards under the technical sector of health, safety and environmental.2 Although used in some countries to evaluate medical practices, it is not the widely accepted model for evaluation of the healthcare system.

Around the same time that ISO was created, Dr W. Edwards Deming, a physicist and statistician from the United States, developed a new process for quality improvement in business. Through this process, all members of a work unit were responsible for continuous monitoring and improvement of products along all steps of production. High frequency errors were identified, corrected, and the resulting outcome monitored for improved quality. Any step in the production process could and would be a continuous target for revision. In this method, focus was shifted from the specific error of an individual to the systemic faults that allowed an error to go unnoticed or proceed uncorrected. The workforce was thus empowered to identify problems and institute a plan of correction. Deming introduced this process which is now known as Continuous Quality Improvement (CQI) and also referred to as Total Quality Management (TQM), Quality Assurance (QA) or Performance Improvement (PI). Used in Japan, TQM quickly led to a revolution in the efficient manufacturing of high-quality goods.

Deming knew that successful management of a complex process or problem required the focused attention of a team of individuals. Although each member was uniquely skilled in a task, the team worked together in developing solutions. The TQM process is well suited for quality improvement in the complex healthcare environment, but has not historically been embraced by the medical establishment. The narrow view that blame for errors be placed on a sole individual and that physicians be allowed autonomous control over medical processes has hindered the acceptance of TQM. This view is changing as organizations realize that medical errors and inefficiencies are usually the result of systemic problems that require multifactorial solutions.

The Evolution of Quality in Healthcare

One of the first efforts to standardize medical delivery occurred in 1917 with the ‘Minimum Standard for Hospitals’ programme set forth by Drs Franklin Martin and John Bowman of the American College of Surgeons (ACS). A one-page, five-point set of criteria was crafted to assess the quality of hospitals3 (see Table 137.1). In 1918, only 89 of 692 hospitals surveyed met the minimum criteria.

Table 137.1 The Minimum Standard.

| ‘The Minimum Standard’ American College of Surgeons 1917 |

1. That physicians and surgeons privileged to practice in the hospital be organized as a definite group or staff. 2. That membership upon the staff be restricted to physicians and surgeons who are a. full graduates of medicine in good standing and legally licensed to practice b. competent in their respective fields c. worthy in character and in matters of professional ethics 3. That the staff initiate and, with the approval of the governing board of the hospital, adopt rules, regulations, and policies governing the professional work of the hospital. 4. That accurate and complete records be written for all patients and filed in an accessible manner in the hospital. 5. That diagnostic and therapeutic facilities under competent supervision be available for the study, diagnosis, and treatment of patients. |

The ACS was responsible for hospital accreditation until 1952 when the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Hospitals (JCAH) was established to take on this responsibility. Led initially by Dr Arthur W. Allen, the JCAH published standards for hospital accreditation in 1953. The JCAH initiatives were also incorporated outside of the United States with Canada offering its own accreditation through the Canadian Commission on Hospital Accreditation in that same year. Over the next two decades, the JCAH grew to include the review of long-term care facilities in 1966 and subsequently mental health, dental, ambulatory care and laboratory facilities. In 1987 JCAH was renamed the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO) to encompass the variety of services and activities offered.4 The organization was rebranded in 2007 and is now generally referred to as ‘The Joint Commission’.

The Joint Commission has been a world leader in healthcare accreditation and a prototype for further development of organizations that monitor and measure the quality of healthcare delivery. Over the past two decades the interest and efforts in healthcare quality have grown exponentially. A variety of national and international organizations have evolved to assist the healthcare industry in meeting new consumer and regulatory demands for high-quality services and programmes.

Organizations Leading Healthcare Quality Improvement

In the United States, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), previously the Agency for Healthcare Policy and Research (AHCRP), is a leader in healthcare quality initiatives. Founded in 1989, this agency of the US Department of Health and Human Services has a mission to improve the healthcare quality, safety, efficiency and effectiveness for all Americans. AHRQ awards millions of dollars in grants to further evidence-based, outcomes research related to healthcare quality improvement. Federal legislation authorizes AHRQ to coordinate health partnerships, support research, and advance information and technology systems. Of the many projects that are overseen by AHRQ, the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTP) and Consumer Assessment of Health Plans (CAHPS) are most prominent. The AHRQ also publishes data on quality and trends in healthcare effectiveness and patient safety. For the past seven years, AHRQ has produced the National Healthcare Quality Report and the National Healthcare Disparities Report.5

The USPSTF is a 15-member, private-sector panel of experts, first convened by the United States Public Health Service in 1984 to develop and assess evidence-based preventive service measures. The hallmark publication of this taskforce titled Guide to Clinical Preventive Services was published in 1989, with a second edition released in 1996 and third edition in 2002.6 Although clinicians and healthcare societies do not always agree upon the details, these guidelines are frequently cited as ‘best evidence’ and considered to represent the ‘standard of care’ in preventive medicine services. This agency has developed recommendations for adults and children in the clinical areas of: Cancer, Heart and Vascular Diseases, Injury and Violence, Infectious Diseases, Mental Health Conditions and Substance Abuse, Metabolic, Nutritional and Endocrine Conditions, Musculoskeletal Disorders, Obstetric and Gynaecological Conditions, Vision and Hearing Disorders, and Miscellaneous conditions.

CAHPS is an organizational databank of healthcare information used by consumers, employers and health plans in evaluating heath care systems and services. Surveys and reporting instruments are used to collect and present information on healthcare providers such as Medicare and the Federal Employees Health Benefits Program. In the private sector, the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) reviews the quality of managed care health plans. Established in 1990, this non-profit group also accredits the healthcare organizations.

NCQA uses the Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) tool to measure and report the performance of health plans and physician practices. More than 90% of US health plans use the HEDIS system which consists of 71 measures and 8 care domains. Such measures could include lead screening in children, blood pressure control and smoking cessation counselling.7

The Institute of Medicine (IOM) is another leader in the development of quality healthcare in America. This non-profit organization was chartered in 1970 as a segment of the National Academy of Sciences. The mission of the IOM is to work outside the governmental framework in providing an independent, scientifically based analysis of the healthcare system. ‘Quality of Care’ was defined by the IOM in 1990 as, ‘the degree to which health services for individuals and populations increase the likelihood of desired health outcomes and are consistent with current professional knowledge’.8

IOM formally launched the first of three phases of a quality initiative plan, beginning in 1996 with an intensive review of the state of healthcare in America. In a statement declaring ‘The urgent need to Improve Health Care Quality’, the IOM began focusing on overuse, underuse and misuse in medical care. During Phase Two, the Quality of Health Care in America Committee convened and has since published several reports, including To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System, and Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. The most recent IOM quality improvement publications have focused on patient safety and performance measures. These titles include: Rewarding Provider Performance: Aligning Incentives in Medicare; Preventing Medication Errors: Quality Chasm Series; and Performance Measurement: Accelerating Improvement.9

The IOM has lobbied for an error reporting system and legislation to protect those who report errors in an effort to promote quality improvement strategies. Twenty ‘Priority Areas for National Action’ have been established based on diseases or conditions that may be best managed using clinical practice guidelines (see Table 137.2). The IOM has established six ‘Aims for Improvement’ in health system function. Healthcare should be: (1) safe, (2) effective, (3) patient-centred, (4) timely, (5) efficient, and (6) equitable. The Committee has also identified ‘10 simple rules for [healthcare system] redesign’ which change the focus of healthcare from provider driven to consumer/system driven care (see Table 137.3).

Table 137.2 Health priority areas.

| 20 priority areas for improvement in healthcare quality |

|

Table 137.3 Rules for health system redesign.

| Ten rules for health system redesign |

1. Care is based on continuous healing relationships. 2. Care is customized according to patient needs and values. 3. The patient is the source of control. 4. Knowledge is shared and information flows freely. 5. Decision making is evidence based. 6. Safety is a system property. 7. Transparency is necessary. 8. Needs are anticipated. 9. Waste is continuously decreased. 10. Cooperation among clinicians is a priority. |

In the United Kingdom, healthcare is provided nationally through a national healthcare service programme within each country. In England, the National Health Service (NHS) has received annual reviews since the Commission for Health Improvement (CHI) was established in 1999 by the national government. In April 2004 this organization was replaced by the Healthcare Commission (HC), which was charged with the task of reviewing and improving the quality of healthcare in the NHS and in the private sector. In April, 2009 the Healthcare Commission merged with the Mental Health Act Commission and the Commission for Social Health Inspection to become the Care Quality Commission (CQC). The CQC collects data on quality of healthcare services that are delivered on a local and national level. This data is available for public inspection. On 1 October 2010, legislation established five essential standards of quality and safety that are required for all agencies that provide health services.10 These standards are as follows:

This legislation moves the NHS quality assurance process from an inspection-reporting process to a continuous quality improvement process.

Other countries in the United Kingdom have their own regulatory agencies and standards for healthcare services. In Scotland, the Regulation of Care (Scotland) Act 2001 established the Scottish Commission for the Regulation of Care (SCRC) based on a set of National Care Standards. The standards define the expected quality of service that is provided and allows for regulatory reports to be generated for health service agencies. In 2004, the Healthcare Inspectorate Wales (HIW) was established to review the quality and safety of all healthcare provided in this country. In Northern Ireland, the Regulation and Quality Improvement Authority (RQIA) monitors and inspects the Health & Social Care Services in Northern Ireland. This agency was established in 2003.

In Australia, evaluation and accreditation of medical practice takes place through the Australian Council on Healthcare Standards (ACHS) and its subsidiary the Australian Council on Healthcare Standards International (ACHSI). The ACHSI uses Australian standards and modifies these to be culturally and internationally appropriate. ACHSI then works in partnership with healthcare accreditation bodies in Ireland, India, New Zealand, Bahrain and Hong Kong through exchange surveyor programmes.

Established in 1974, ACHS is an independent body comprised of healthcare leaders, governmental representatives and consumers. ACHS accredits programmes using a standardized model called the Evaluation and Quality Improvement Program (EQuIP). EQuIP sets standards in two broad categories: (1) patient care services across the continuum of care, and (2) the healthcare infrastructure. EQuIP standards are revised every four years. On 1 July 2011 the version EQuIP5 will be implemented.

ACHS also provides comparative information on the processes and outcomes of healthcare through the Clinical Indicator Programme. Using 23 Clinical Indicator Sets with over 350 Clinical Indicators, data submitted from a healthcare organization can be quantitatively measured and objectively compared with other organizations and with national aggregate data. Outlying data generates a ‘flag’, which can alert the organization to quality control problems.11

In 2006 the Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care (ACSQHC) was established to develop a national framework for improving safety and quality across Australia.12 This commission is charged with:

- identifying priority healthcare issues and setting policy directions

- disseminating knowledge and advocating for heath safety and quality

- public reporting of health safety and quality data

- coordinating and developing national health and safety data bases

- advising Health Ministers

- recommending national safety and quality standards.

Australia is also the original host country of The International Society for Quality in Health Care (ISQua), which moved to Ireland in 2008. This non-profit organization ‘Accredits the Accreditors’ and provides services and information on healthcare quality to medical providers and consumers. Over 50 healthcare organizations, standards and surveyor programmes are accredited through ISQua.13 ISQua hosts an annual international summit to discuss performance indicators and promote a multidisciplinary approach to quality improvement programmes. Participants include health policy leaders, researchers, healthcare professionals and consumer organizations. The ISQua also supports the International Journal for Quality in Health Care, a peer-reviewed journal in its 22nd year of publication.

Models for Evaluating Quality

The approach to quality in healthcare bears many similarities to quality improvement in the commercial sector by focusing on key issues of safety, effectiveness, consumer satisfaction, timely results and efficiency. Within Europe, there is much diversity in the oversight and governmental mandates for quality of healthcare practice. Most legislation surrounds the health system and hospital accreditation process, with less emphasis placed on individual clinical practices. Based on the established healthcare and payer system, each country may address quality control quite differently.

To better understand the most common methods of measuring healthcare quality, a survey of European External Peer Review Techniques (ExPeRT) was initiated.14 The results of this ExPeRT Project, revealed four commonly used quality improvement models: healthcare system accreditation, ISO certification (both discussed previously in this chapter), the European Foundation for Quality Management (EFQM) Excellence Model, and the Visitatie peer review method.

The EFQM is a global non-for-profit foundation founded in 1988 by presidents of leading European companies and which uses the ‘EFQM Excellence Model’ for assessing the quality of an organization. The framework for this TQM approach includes nine criteria by which an organization is evaluated on ‘what it does’ and ‘what it achieves’. A Quality Award is presented after a process of self-assessment and internal review. Members within the EFQM foundation learn from each other and share best practices for improving the quality of service provided to the consumer.15

The Visitatie model originated in the Netherlands and focuses on medical practice specifically, rather than on business practices broadly. Visitatie is a peer review consultation process that uses practice and practitioner-derived guidelines to evaluate patient care. Emphasis is placed on individual and team performance, not organizational structure or outcomes. Unlike other methods, Visitatie does not result in a certification or accreditation award. Because the focus is on improving care through peer feedback, there is no ‘pass/fail’ or punitive outcome. This model is becoming popular across Europe as a method for personal and peer review of medical care. Groups who have used this consultation approach to practice management reported more success and fewer barriers when implementing quality improvement changes in practice.16

Quality Improvement in Geriatrics

The elderly population is prone to adverse outcomes, especially when healthcare delivery is fragmented. Research has demonstrated that adverse health events are more likely to occur in the elderly population and that the risk of adverse hospital events is twice as high for individuals over age 65.17, 18 Preventive medicine for seniors includes identifying patient safety issues that can lead to functional decline and poor health outcomes. Identifying risk factors for decline and providing early intervention is effectively approached though a healthcare team-based TQM process.

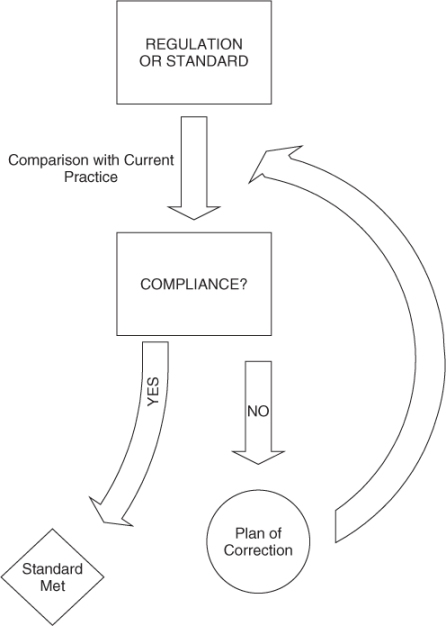

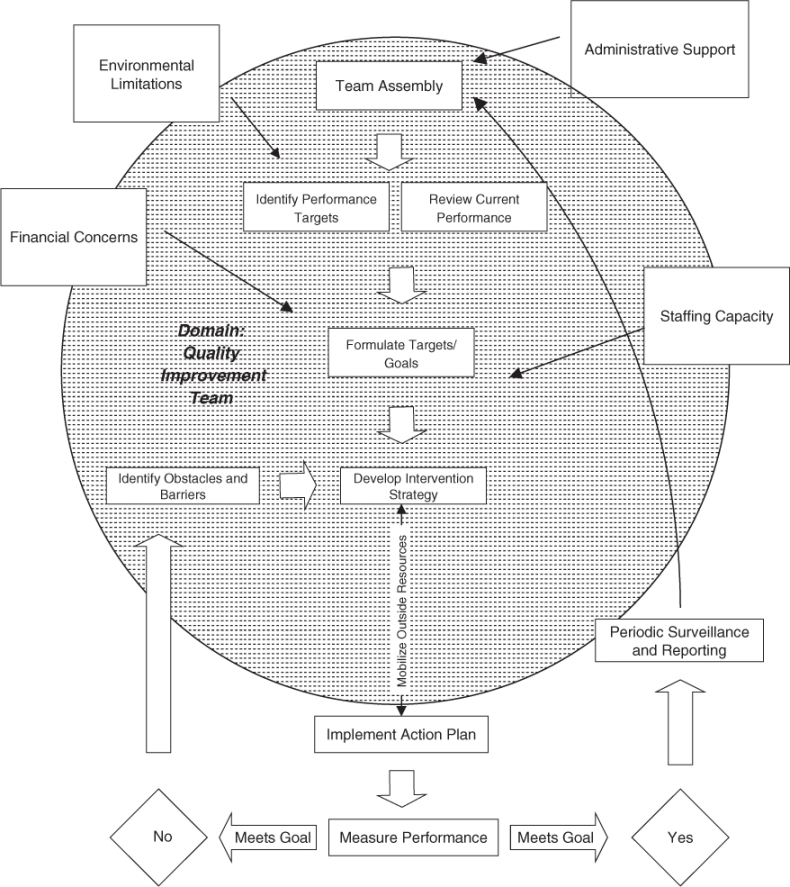

Quality in healthcare has evolved from a reactive Quality Assurance (QA) model (see Figure 137.1), to a proactive TQM model (see Figure 137.2). Instead of focusing on compliance and adherence to external regulations or standards (QA model), TQM focuses on the continuous process of improving care relative to current internal practices. TQM involves not only change in practices on an individual level, but also change in process on a larger scale that can benefit a broader population.

In the TQM team process, each discipline reports data collected on patient care since the previous team meeting, as well as areas of ongoing concern or newly identified issues. The team discusses markers (indicators) of quality and establishes targets to achieve by the next meeting. The team then develops a plan for achieving these targets. A method of measuring performance and collecting data is established. An individual or subcommittee is then assigned to carry out the quality improvement protocol and provide a progress report at the next meeting. If the goals are achieved, data continues to be tracked over time to identify trends in performance and to maintain the established goals. If previously established quality targets are not met, barriers or obstacles are explored.

Geriatricians are in a unique position to take a lead in the healthcare quality improvement process. Interdisciplinary management and teamwork are at the core of geriatrics training and practice. Geriatricians are comfortable entrusting responsibility to team members and sharing in the problem-solving process. This is a requirement for the success of TQM programmes. Geriatricians are also more likely than other physicians to have experienced the TQM process, as this is a routine activity in long-term care facilities. Through TQM, data on events such as falls and dehydration are tracked and shared with the staff at regular intervals. Trends are then discussed and solutions proposed when outlying results are identified.

Quality Indicators

In the United States, markers for quality in nursing home care, termed ‘Quality Indicators’ have been developed and tracked by the federal government through the completion of the required Minimum Data Set (MDS) resident evaluation questionnaire19, 20 (see Table 137.4). Quality is assessed on these indicator domains using ‘Quality Measures’. These measures include sentinel events such as faecal impaction or dehydration, and incidence/percentage of residents with certain conditions such as indwelling catheters and pressure ulcerations. Data on these measures is collected and reported federally through the MDS, and facilities are then compared against local and national facility averages. Facilities with outlying rates on the quality measures are ‘flagged’ which may prompt investigation or oversight by the state nursing home regulatory board.

Table 137.4 Measures of nursing home quality.

| Domain/Quality Indicator | Quality Measure |

| Accidents |

|

| Behaviour/Emotional Patterns |

|

| Clinical Management |

|

| Cognitive Patterns |

|

| Elimination/Incontinence |

|

| Infection Control |

|

| Nutrition/Eating |

|

| Pain Management |

|

| Physical Functioning |

|

| Psychotropic Drug Use |