Over the past 40 years, breast restoration following breast removal for cancer has been transformed from a rarity to the standard of care in major U.S. cancer centers. Concurrent with this development have been changes in extirpative surgical practices, medical and radiologic cancer treatments, and financial and political factors impacting the management of breast cancer. Significant among the latter was the passage of the Women’s Health and Cancer Rights Act (WHCRA) in 1998. This federal law was inspired by the case of a woman from Long Island, New York who was denied breast reconstruction coverage by her insurer on the grounds that the company considered it to be a “cosmetic” rather than “medically necessary” operation. The WHCRA mandates that health insurance companies and group health plans which cover mastectomies must also provide coverage of mastectomy-related procedures, including breast reconstruction surgery, prostheses, and procedures to restore symmetry in the contralateral breast.1 The practical implication of this law is that, with few exceptions, every woman who now undergoes a mastectomy covered by her insurer also has coverage for subsequent breast reconstructive procedures. The authors feel strongly that every woman who undergoes a mastectomy should at minimum be offered a consultation with a reconstructive surgeon to discuss the possibility of breast reconstruction, preferably prior to any breast surgery so as to optimize the eventual outcome.

The frequency of breast reconstruction, and the techniques used, has been greatly impacted by changes in the surgical treatment of carcinoma of the breast. Radical mastectomies, so common a half-century ago, are performed only rarely today. An increasing emphasis on breast conservation means that for many patients, lumpectomy or quadrantectomy are deemed sufficient to gain surgical control of their cancers. Many of these patients will do well from an aesthetic standpoint, with no reconstruction needed; in those cases where a significant partial breast deformity necessitates reconstructive surgery, autologous tissue flaps or fat grafts are the preferred techniques.2 The reconstruction of the conserved breast will not be discussed in this chapter, which focuses on implant-based reconstruction after mastectomy.

For those patients with breast disease requiring a mastectomy, or those who mastecctomy amonst different treatment options, the use of modified radical and simple mastectomies and the techniques of skin-sparing and nipple-sparing have resulted in defects that are more amenable to reconstruction than in the days of Halsted. Simultaneously with the development of these techniques, the technology of prostheses for breast reconstruction has evolved since the early use of breast implants in the 1960s by Cronin and Gerow.3 The use of tissue expanders (TEs) and breast implants has been successful to the point where the majority of breast reconstruction done in the United States at this time is implant based.4 Alternative means of breast reconstruction, including flap-based reconstruction and autologous fat grafting, are discussed in Chapters 155 and 158, although we will touch upon the factors that may make one choose these options over implant-based reconstruction.

Many patients considering implant-based reconstruction will be aware of the controversy surrounding breast implant safety. Some will be very knowledgeable; some will be less so; some will be grossly misinformed. A full historical review of this controversy can be found elsewhere.5,6 It is important that the breast reconstructive surgeon be aware of the findings of the major studies regarding silicone implants, and of the reasons why they are now back on the market in the United States and chosen by many patients.4,7 Inquisitive patients may also be aware of the more recently described (and exceedingly rare) lymphomas which can arise at breast implant placement sites.8,9 Any discussion of implant-based reconstruction must include a thorough disclosure of the risks and remedies associated with implants. The decision about the type of implant to chose will be discussed more below.

A good outcome in breast reconstruction depends upon a number of factors, and high on this list is an excellent relationship between the extirpative and reconstructive surgical teams. For the patient that knows she desires breast reconstruction, such a relationship allows for good preoperative planning, and the subsequent optimization of outcomes. Ideally, this relationship will allow the majority of patients who desire reconstruction to undergo immediate reconstruction, meaning that the surgical reconstruction process begins as soon as the mastectomy is complete.

The initial step in any reconstructive surgical planning is determination of the defect to be filled. The defects from radical mastectomies were not amenable to implant-based reconstruction, as the removal of the pectoralis musculature and associated loss of the anterior axillary fold left inadequate tissue for coverage of an expander or implant. However, the modified radical and the simple mastectomies (with or without sentinel lymph node biopsy) that are in common use today both typically leave the reconstructive surgeon with enough tissue to allow for expander or implant placement. Other factors, however, must also be considered, including the location of scars, the quality of the patient’s tissues (particularly any prior radiation), and the amount of skin present.

One critical question to address early in the planning stage is whether the patient will require unilateral or bilateral mastectomies. The decision to perform a prophylactic mastectomy of the contralateral healthy breast is beyond the scope of this chapter, and in general is not the purview of the reconstructive surgeon. Patients will ask, however, about the aesthetic appearance of unilateral versus bilateral breast reconstructions. In our practice, we discourage patients from making a determination about double mastectomy on cosmetic grounds but acknowledge that for implant-based reconstruction, breast symmetry is more easily created if performed on both breasts.

For patients undergoing unilateral mastectomy who desire reconstruction, an additional topic that must be broached early in the reconstructive process is whether the patient is amenable to having surgery on the healthy breast in order to obtain better symmetry. Within reason, such surgeries will allow the patient to change the size or shape of her uninvolved breast to match the reconstructed one. The range of possible techniques is broad and includes the entire armamentarium available to the breast plastic surgeon: implant augmentation, mastopexy, breast reduction, liposuction, and/or fat grafting can all be employed to change the size or shape of the uninvolved breast and reestablish breast symmetry. Such surgeries to achieve breast symmetry are ideally performed at least several months after the patient has recovered from her breast reconstruction and the implant has settled, giving the plastic surgeon a better idea of the size and shape of the breast to be matched.

Recent trends in breast cancer surgery have favored greater preservation of native tissue, and skin-sparing and more recently nipple-sparing mastectomies are now increasingly employed.10,11 For the reconstructive surgeon, these developments are generally welcome, as they provide more soft tissue to cover TEs and implants, but with a crucial caveat. The preservation of most or all of the skin covering the breast at the time of mastectomy leaves a physiologically vulnerable skin flap, as the perforating blood vessels that traverse the breast tissue are removed. In thinner patients in particular, the viability of preserved skin can be tenuous due to poor blood supply. The reconstructive surgeon must ensure that there is adequate perfusion before placing an implant or TE, as necrosis of the overlying skin will lead to implant exposure and removal. If the surgeon feels that some of the preserved skin (including the nipple) is unlikely to survive, resection of the threatened area is indicated. The authors always caution patients prior to surgery that no promises can be made regarding preservation of the skin or nipples. In rare cases, it may be necessary to change the plan for immediate reconstruction to delayed reconstruction, if the tissue health or other patient factors made immediate reconstruction ill-advised.

Some patients will not and/or should not undergo immediate breast reconstruction—they may be poor candidates for other health reasons, including active smoking; they may want to focus on breast cancer treatment and not wish to undergo reconstruction at that time; or they may experience complications with attempted immediate reconstruction that necessitate expander or implant removal. Such patients may still be candidates for delayed breast reconstruction, including implant-based reconstruction techniques. The authors will wait a minimum of 3 months after prior surgeries before attempting delayed reconstruction, and longer in patients having difficulties with healing. Delayed reconstruction with implants requires either tissue expansion or tissue transfer in virtually all cases, as the skin contracture that occurs precludes the direct placement of implants.

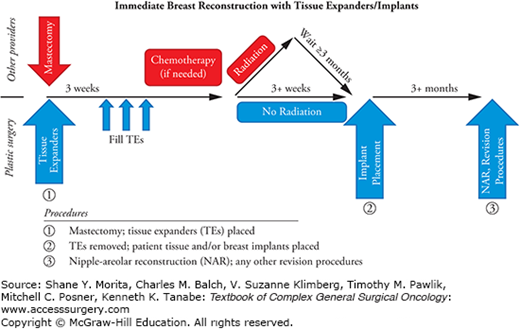

Plastic surgeons who perform breast reconstruction use a variety of algorithms to determine the reconstructive technique employed to treat a given patient. Doctors who do not perform microsurgery may only offer implant-based reconstruction; conversely, some microsurgical breast surgeons feel that autologous tissue yields a better result and recommend it for the majority of their patients. The factors that go into the decision to pursue implant-based breast reconstruction are, therefore, highly individual, and no one approach is right for all patients or for all plastic surgeons. The immediate placement of a TE is our default technique for breast reconstruction (see flowchart in Fig. 154-1). Placement of TEs at the time of mastectomy is performed for most patients who desire reconstruction, regardless of whether they will require radiation or chemotherapy, prefer saline or silicone implants, or plan to forgo implants and use autologous tissue flaps. Other surgeons feel that the placement of TEs is unnecessary in a patient who plans to undergo an autologous tissue breast reconstruction. In our opinion, however, the TE acts to preserve the skin envelope of the breast and thus gives a superior cosmetic result even in those patients who do not receive implants. Moreover, using a single technique initially allows the patient and her doctors to defer any final decision on reconstructive technique until after the patient has recovered from her mastectomy and undergone any needed chemotherapy and/or radiation. The TE acts as a placeholder, and no final reconstructive options are precluded. It also allows us to delay a flap reconstruction until the final pathology on the cancer resection is reported and a definitive decision regarding adjuvant radiation therapy has been made.

Some patients, however, who are certain they want autologous tissue reconstruction may find the prospect of TE placement and filling to be burdensome; inarguably, it adds time and an additional procedure to the breast reconstruction process. For these patients, an immediate reconstruction with either a pedicled or a free tissue transfer is an option. These procedures are discussed in the chapter on autologous breast reconstruction (see Chapter 155).

One of the first questions to ask when a breast cancer patient desires reconstruction is whether they can safely undergo the procedure. In our practice, we do not perform breast reconstruction on active tobacco users. We feel that the elective nature of breast reconstruction coupled with the high incidence of complications in smokers12–15 makes performance of breast reconstruction in this population ill-advised, especially given the stress already placed on the skin of the breast by the mastectomy. We counsel active smokers to undergo surgery to treat their breast cancer initially. Afterward, they can work to quit smoking and then return for a delayed breast reconstruction. A smoking cessation program can be helpful for those patients who still wish to pursue reconstruction. We require a negative urine cotinine test 2 weeks prior to surgery in any patient suspected of being noncompliant; we would rather delay a reconstruction than have a high risk of implant exposure or infection due to nicotine use.

Other factors important in determining whether a patient is a candidate for implant-based reconstruction relate to overall health. Diabetes, obesity, and compromised immunity are considered relative contraindications to implant-based reconstruction due to the higher risk of implant exposure or infection.15,16 The more severe the condition, the stronger the contraindication to implant-based breast reconstruction. The junior author (KW) uses cutoffs of 7.0 for HbA1c and /or 40 for body mass index (BMI) for immediate reconstruction; above these values, delayed breast reconstruction is recommended over immediate TE placement. Patients with a history of hypertrophic or keloid scarring must be cautioned that breast incisions are notorious for producing unsightly scarring. Excessive scarring can be unpredictable, occurring on one side while sparing the other or manifesting medially while the lateral incision heals normally. Most of our breast reconstruction patients who successfully undergo tissue expansion will choose to proceed with implant placement. There are, however, specific instances where free tissue transfer becomes more favorable or even advisable. Relatively speaking, a patient who undergoes a unilateral mastectomy and has a natural breast on the contralateral side is a good candidate for autologous tissue reconstruction, as the difference between a natural breast and an implant-reconstructed breast will tend to widen over time—weight gain or loss will affect the natural breast more, and aging-related involution and ptosis will manifest more on the unreconstructed side. A subset of patients will have an aversion to implant-based reconstruction, in some cases due to lingering concerns from the silicone implant controversy, but more often as a manifestation of her broad distrust of any elective long-term implants. In such cases, patients may come to the reconstructive surgeon with a strong preference for autologous tissue over implants.

A few conditions will lead us to recommend the use of autologous tissue, either alone or in concert with implants, to our breast reconstruction patients: (1) history of breast radiation, (2) necrosis of the mastectomy skin flap, and/or (3) infection of the TE pocket. The senior author (JA) believes that the risk of implant exposure is unacceptably high in irradiated patients undergoing simple implant-based reconstruction; these patients are typically offered either flap coverage over an implant on the radiated side, in the form of a pedicled latissimus dorsi musculocutaneous flap, or total free tissue reconstruction of the breast. Patients with a history of infection of the breast after mastectomy, particularly those necessitating removal of the TE and delay of reconstruction, also benefit from the added blood flow associated with an autologous tissue flap for coverage of, or replacement of, the implant.

One critical aspect of breast implants that must be stressed to and be accepted by all such patients is that they are not “lifetime” devices. While durable and safe, there is a reasonable chance of device failure, particularly in young cancer patients who will potentially have reconstructed breasts for many years to come. Patients should recognize that there is a strong possibility that they will need to undergo implant removal or revision in the future. Implant durability is discussed further in the section below on silicone versus saline implants.

In addition to determining overall health, with special attention to smoking, keloids, and /or diabetes, and discussing personal preferences for breast reconstruction, the physical exam is crucial for determining the advisability of pursuing implant-based reconstruction. Any previous breast surgeries are relevant to the likely success of breast reconstruction, although even breasts with a history of previous surgery can be successfully reconstructed.17

With regard to the recent trend toward nipple-sparing mastectomy, it is important to choose patients wisely to manage expectations and to discuss the operative plan in depth with the reconstructive surgeon prior to placement of TEs. A patient with a severely ptotic breast is, in our opinion, a poor candidate for nipple preservation at the time of mastectomy. While the nipple in such a patient can be saved, it results in a distorted breast with poor nipple positioning. Such a patient is better served by nipple reconstruction, if desired, after the reconstruction of the breast. Patients who are offered nipple preservation must be informed that their nipples will be insensate after mastectomy, and recovery of sensation is variable and often incomplete.18 The obese patient must be approached with caution when considering breast reconstruction. Certainly, all women undergoing a mastectomy should be given the option of discussing reconstruction with a plastic surgeon, but that does not mean all women are good candidates. The obese patient presents several challenges. In addition to the higher operative risk and the increased rate of infection and wound healing problems,19 it is hard to get a satisfactory result with implants in an obese patient. The largest silicone breast implants currently approved in the United States are 800 cc in size; the largest saline implants can be over-filled to 1000 cc. Even implants this large can get “lost” in the chests of the obese woman, leading to results that disappoint both surgeon and patient. Unfortunately, autologous tissue transfer for breast reconstruction in the obese patient also has pitfalls. In such a patient who is interested in reconstruction, one option that can be offered is to delay reconstruction until after significant weight loss has occurred and the patient’s weight has stabilized.

In addition to physical screening of patients, the psychology of the patient must be assessed preoperatively, and in some cases issues must be addressed preemptively to avoid postoperative dissatisfaction. It is critical that the patient realize that their breasts will be quite different after mastectomy and reconstruction, no matter what technique is pursued. In our experience, patients with prior breast augmentation have a more difficult time accepting the reality of the changes in their breasts after mastectomy. Patients must be warned that breast and nipple sensation will diminish, and while some recovery is possible, it is unlikely to be complete. Patients with underlying depression or body-image issues may be prone to greater dissatisfaction with the reconstructed breast, even when the results are quite satisfactory (or even superlative) from the standpoint of the surgeon. Caution is needed when patients voice unrealistic expectations of how they will look or what their breasts will look like after reconstruction. As with all aspects of reconstructive surgery, preoperative education is crucial to preventing postoperative anger, confusion, and dissatisfaction.

One of the first decisions that must be made regarding any breast reconstruction is whether to perform immediate versus delayed reconstruction. The advantages of an immediate reconstruction are self-evident: one less surgery; quicker time to completion of reconstruction; never having to live without any breast mound. Furthermore, by avoiding breast skin contraction and adherence to the chest wall, immediate reconstruction increases the chance that the eventual breast will have smooth, natural-appearing skin coverage. However, and perhaps less obviously, there are some advantages to delayed reconstruction. Delayed reconstruction allows both the tissue and the patient as a whole to recover from the mastectomy. For many patients, there is uncertainty about the need for additional treatment with radiation and/or chemotherapy that will not be resolved until the pathology results from the mastectomy are back. Patients who are facing a prolonged treatment course may feel that focusing on their cancer treatment is preferable and that reconstruction can wait until later. Studies have found no consistent difference in eventual satisfaction rates between immediate and delayed reconstruction patients.20–23

As discussed above, for patients who want immediate reconstruction, we prefer to perform a staged, tissue-expander–based reconstruction. We believe this has benefits from a practical standpoint (not starting a microvascular case immediately following the sometimes lengthy mastectomy +/− lymph node dissection), from a clinical perspective (allowing for final pathology results before performing the definitive reconstruction) and from a cosmetic standpoint (preservation of more of the breast skin envelope).

From the standpoint of whether an immediate or a delayed reconstruction is advisable for a patient who could safely choose either, we ultimately leave that decision to the patient. If a patient is truly uncertain, then we generally advise that they wait and undergo a delayed reconstruction.

The vast majority of implant-based reconstructions are performed in a staged fashion, with a TE used to expand the skin envelope, stretch the pectoralis major muscle, and create a capsule that will later be filled with an implant. The benefits of this approach are numerous and include improved preservation of the breast skin, better cosmetic outcomes, and the ability to create larger breasts than could be done otherwise. Nevertheless, a minority of patients will request an immediate implant placement. Some of these patients are unwilling or unable to undergo the process of tissue expansion; as long as these patients are fully informed, and willing to accept both a breast of a smaller size than would otherwise be possible and a possibly less than ideal outcome, it is permissible to proceed. However, there are also rare cases where this approach might be recommended outright. Specifically, a healthy patient who wishes to have a significantly smaller breast may be an excellent candidate for single-stage reconstruction (direct-to-implant reconstruction). Similarly, a patient who has small breasts, is happy with her breast size, and is undergoing prophylactic nipple-sparing mastectomies could be a good candidate. The authors caution against the use of this technique in the setting of a skin flap that is very thin or that appears compromised intraoperatively. Placing an implant which causes excessive tension on already traumatized skin can result in skin necrosis or implant exposure. In these cases, we recommend placing a TE with only a small amount of fluid so as not to place too much tension on the tenuous skin flap.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree