CHAPTER 13 Immunizations for Immigrants

Health Disparities and Risk of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases in Immigrants

Risk of disease is greater outside the US for many vaccine-preventable diseases. Endemic measles, rubella, and polio no longer occur in the US, and disease due to diphtheria and Haemophilus influenzae type b has been eliminated almost completely.1–5 The fact that tetanus occurs only rarely in the US is a result of high vaccine coverage.6 Varicella and pneumococcal disease in young children have been reduced by routine infant immunization.7,8 Pertussis has been decreased significantly by infant immunization, though outbreaks continue to occur, especially in adolescents and adults.9

A number of vaccines given in the US are not administered routinely in other countries. Lack of widespread availability of Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) and hepatitis B vaccines was reflected in significant differences in vaccination coverage levels between foreign-born and US-born 19–35-month-old children in 1999–2000. For Hib, coverage rates were 87.2% in foreign-born children compared with 95% in the US-born; for > 3 doses of hepatitis B vaccine, rates were 73.6% for foreign-born and 89.4% for US-born children.10 For adults, gaps exist in pneumococcal immunization rates among ethnic populations compared to the US general population. A survey of Cambodian and Vietnamese adults revealed rates of pneumococcal immunization below those of the US general population: 18% for the Cambodian group, 40% for the Vietnamese group, and 62% for the US general population.11 Other vaccines given in the US that are not available routinely in some other countries include varicella, hepatitis A, and meningococcal vaccines. In early 2006, a vaccine against rotavirus was licensed in the United States for use in infants; a second vaccine is licensed in some other countries.12,13 Immigrants are likely to have been exposed repeatedly to rotavirus in their countries of origin, as are most children and adults in the US. Current CDC recommendations call for immunizing all females at age 11–12 with human papillomavirus vaccine (http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr5602a1.htm?s_cid=rr5602a1_e).

Immigrants who have easy access to the US health system, children who attend public schools and therefore must meet immunization requirements to attend, and those who require immunizations to meet occupational requirements are likely to be offered catch-up immunization and may not differ from local populations in risk for vaccinepreventable diseases. Unfortunately, not all immigrants have easy access to healthcare. Undocumented status, language barriers, prohibitive costs, competing priorities, and lack of understanding of need for preventive health measures all may serve as barriers to adequate immunization. It is helpful to identify, where possible, the groups of immigrants that remain susceptible to VPDs, so that interventions can focus on decreasing meaningful disparities in immunization. Measuring disparities in vaccine coverage is the critical first step to informing public health policy around targeting specific groups for interventions. As discussed by Barker et al., statistically significant differences may not, however, be meaningful from a public health standpoint.14 When public health programs are not practical or available to address health disparities in immunizations, the burden falls on the individual health professional. Individual practices may need to make special efforts to identify and immunize the young Hispanic woman against rubella, the elderly Cambodian gentleman against pneumococcal disease, and school-aged Somali children against hepatitis B. The following sections address differences in susceptibility to vaccine preventable-diseases in immigrants compared to US-born populations, and identify populations or groups at greatest risk of disease. These points are summarized in Table 13.1.

Table 13.1 Immunization issues for immigrants by disease

| Disease | Risk of contracting disease in the US compared to US-born population | Special considerations for immigrants and their contacts |

|---|---|---|

| Measles | Same or decreased | Infants may be at increased risk of importing disease; assure protection of US-born who will have contact with immigrant infants |

| Rubella | Increased in some groups | Assure protection of Hispanic individuals, especially those in the child-bearing years |

| Varicella | Increased in some groups | Serotesting cost-effective in most cases (especially older children and adults) before immunizing |

| Tetanus | Same or increased | Increased risk in some groups, such as Mexican-born and island populations |

| Diphtheria | Same or increased | Increased risk in some groups, such as Mexican-born |

| Hepatitis B | Increased | Immunize new arrivals after testing for disease; immunize household contacts of new arrivals |

| Polio | Unknown | Immigrants recently immunized with OPV may shed vaccine strain virus for some time after arrival in the US |

| Hepatitis A | Decreased in older individuals; may be increased in young children | Immunize household contacts of new arrivals |

| Pertussis | Unknown |

Measles

There is at this time no endemic measles virus circulating in the United States and vaccine coverage appears to be sufficient to prevent sustained transmission of measles within the US. The gap in coverage with measles vaccine between white and nonwhite children was reduced from 18% in 1970 to 2% in the 1990s.15 Measles cases that were imported or import-related accounted for 80% of the 216 measles cases reported in 2001–2003 in the United States.16 The largest number of imported cases was from China or Japan and included cases in international visitors as well as US residents traveling abroad.16 Internationally adopted children from China have been associated with outbreaks of measles that have resulted in documented transmission within the US.17,18

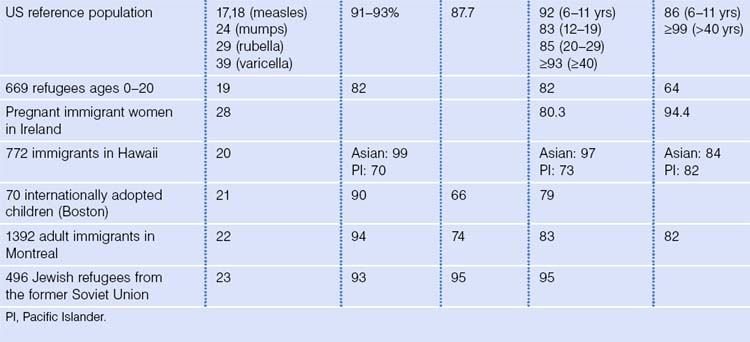

Most immigrants to the US will have received measles-containing vaccine or will have had natural infection with measles. In fact, foreign-born children from 19–35 months of age were significantly more likely to have received measles-containing vaccine than US-born children in one study.10 High prevalence of measles antibody in immigrant groups has been documented in several studies, and is similar to the calculated population immunity of 93% in the US general population and the 91% prevalence of antibody in a study of 508 young blood donors (Table 13.2).19–25 Older children and adults who arrive in the US without immunization records are unlikely to be susceptible to measles, but efforts to limit needless immunization suffer from inability to determine quickly and easily who has immunity to measles. Immigrants at highest risk of developing measles in the US are infants or other individuals who did not yet receive measles-containing vaccine, and who were exposed before departure for the US.

Mumps

A dramatic reduction in cases of mumps in the US occurred, beginning in the early 1990s. Fewer than 300 cases of mumps were reported in the US each year until December 2005, when an outbreak of mumps began in the state of Iowa, spreading to involve more than 5000 individuals in 45 states as of October 2006.26,26a There are no data to suggest that a disproportionate number of cases occurred in immigrants. Mumps vaccine is not included in routine immunizations in many countries, though many individuals may be protected after natural disease. A serosurvey in US Navy and Marine Corps recruits measured an antibody prevalence of 87.7%.27 Seroprevalence studies of several immigrant groups documented antibody to mumps in 66% of internationally adopted children, 74% of new immigrants to Canada, and 95% of Jewish refugees from the former Soviet Union.23–25

Rubella

Elimination of endemic transmission of rubella in the United States was confirmed by an independent panel of experts convened in October 2004.6 Since 1998, the majority of cases of rubella in the United States occurred in individuals born outside the country, mostly in the Western hemisphere. In 1998–1999, more than half of reported cases occurred in foreign-born individuals; for the 432 individuals for whom country of origin was known, 75% were born outside the US. Most cases occurred in individuals of Hispanic ethnicity.28 In addition, almost all infants with congenital rubella syndrome (96% of 23 infants) in 1998–2000, and another affected infant born in 2005, were born to non-US-born women.29,30 Rubella vaccine is not routine in many countries but many individuals are protected by immunity from disease. Seroprevalence data available from immigrants from several countries suggest that most individuals are protected (see Table 13.1).21–25,31 For comparison, seroprevalence rates in the US have been reported as 92% in those ages 6–11, 83% in those 12–19, 85% in those 20–29 years, 89% in those 30–39 years, and > 93% in those > 40 years.32 The imperative to prevent congenital rubella syndrome makes it important to assure the ability to identify and immunize susceptible immigrants, especially women in their child-bearing years.

Tetanus and diphtheria

Fewer than 50 cases of tetanus are reported in the US each year. Since 1984, only three cases of neonatal tetanus have been reported; two in children of women born outside the US who had not received immunization with tetanus toxoid.33 There was an average of 43 cases of tetanus reported each year in the US in 1998–2000; although incidence was higher in persons of Hispanic ethnicity, countries of origin of those infected were not reported.34 Tetanus can be prevented only by immunization; immigrants who are not immunized by the time of arrival will not be protected by high immunization rates in the US.

Diphtheria is rare in the US with 53 cases reported from 1980 to 2001.35 Risk of contracting diphtheria is likely higher for most immigrants in their country of origin than in the US. The National Immunization Survey of 1999–2000 reported that foreign-born children 19–35 months of age were less likely to have received four or more doses of tetanus- and diphtheria-containing vaccine.10

In a population-based serosurvey of tetanus immunity in the US as of 1988–1991, 69.7% of Americans > 6 years of age had protective levels of tetanus antibodies (>0.15 IU/mL), though Mexican-Americans had a significantly lower rate of immunity (57.9%) compared to non-Hispanic whites (72.7%) or non-Hispanic blacks (68.1%).36 A small study of tetanus antibodies in adults > 65 years of age showed that 45% of those born outside the US had adequate antibody levels (>0.17 IU/mL) compared with 53% of those born in the US.37 Subsequent serosurveys of tetanus and diphtheria antibodies from 1988 to 1994 continued to show that Mexican-American adults were less likely compared with the non-Hispanic white reference population to have protection against tetanus (66% versus 74%) and diphtheria (55% versus 60%).38 A serosurvey of blood donors in Toronto showed that foreign-born individuals were more likely to be susceptible to diphtheria (27% versus 18%) and tetanus (27% versus 12%) than those born in Canada (Table 13.3).39

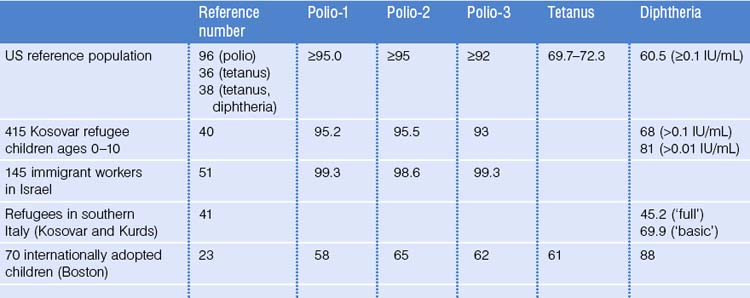

Table 13.3 Prevalence of antibody to polio, tetanus, and diphtheria in selected immigrant groups and US reference populations

Limited seroprevalence data from refugees and internationally adopted children document a range of antibody levels.23,40,41 Differences in testing methods and cutoff values chosen for various studies and lack of agreement on standardized cutoffs make comparison of results from different groups challenging. In the absence of simple and cost-effective ways to determine immunity to tetanus and diphtheria, healthcare professionals must be prepared to provide a complete three-dose primary series of tetanus toxoid to all, and to plan for boosters every 10 years throughout life. In the spring of 2005, two tetanus, diphtheria, and acellular pertussis (Tdap) vaccine products were licensed for use in adolescents and, for one product, adults.42 For individuals age 11 and over who do not have a documented series of tetanus and diphtheria vaccine, it is recommended that one dose, preferably the first, of the series be Tdap. For those who have completed a primary series, it is recommended that the adolescent booster dose be Tdap, as long as at least 2 years have passed since the most recent dose of DTaP, DTP, or Td.42 Adults may be given a dose of Tdap to replace one of their usual Td boosters.42a

Varicella

Before introduction of varicella vaccine in the US, a large (21 288 participants) serosurvey of varicella antibody found that 86% of children 6–11 years of age and > 99% of those 40 years of age or older were seropositive. Non-Hispanic black children were 40% less likely to be seropositive compared with white children.43 Varicella transmission has decreased in the US since initiation of routine childhood immunization.7 Outbreaks continue to occur, and risk to immigrants will be related directly to whether they are immune to varicella when they arrive in the country. Seroprevalence studies indicate that although the majority of immigrants show evidence of antibody to varicella, some groups, especially those from the hottest parts of the tropics, or living in isolated communities before emigration, may be more likely to lack sufficient antibody.21,24,44 A study in military recruits found that those enlisting from outside the continental US, especially those from island territories, were less likely to have antibody to varicella.27 Seroprevalence data for selected immigrant groups are listed in Table 13.3.

Hepatitis B

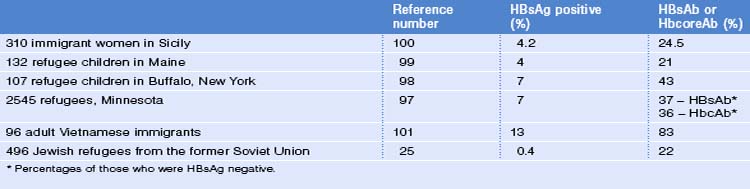

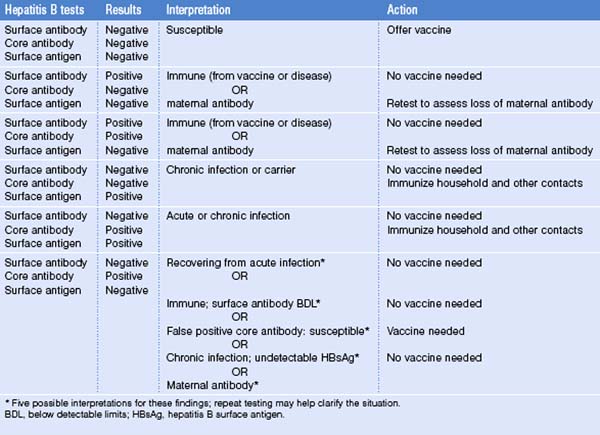

Rates of infection with hepatitis B are well known to be higher in many countries outside the United States (see Ch. 22; Hepatitis B). Immigrants who live in the US may be at greater risk of acquiring hepatitis B due to increased exposure to infected relatives or household members from countries with higher rates of hepatitis B infection, and because they may be less likely to have received hepatitis B vaccine. The greater problem, though, is the number of immigrants who arrive in the US already infected with hepatitis B (Table 13.4). Almost half (8/19) of acute hepatitis B cases in children and adolescents ages 0–19 reported in 2001–2002 were born outside the US; six cases were in internationally adopted children.45 Hepatitis B infection occurs overall in about 5–7% of internationally adopted children, though higher rates have been reported, especially in adoptees from Romania.46 Risk also may be greater in older adoptees and those adopted from countries in Asia and sub-Saharan Africa, especially where hepatitis B vaccine is not administered. Immigrant groups at increased risk of hepatitis B include those from Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. For this reason, it is important to screen individuals from such groups for hepatitis B infection before immunizing (Table 13.5).

Protection against hepatitis B is especially important in immigrant communities with increased rates of hepatitis B infection. In addition, identification of those who are infected is important because it may identify those eligible for treatment or monitoring for chronic liver disease and liver cancer, as well as identify opportunities for prevention of transmission. Strategies to improve immunization coverage in these groups must address the context in which the disease is perceived, and must be undertaken with attention to factors that may serve as barriers to acceptance of vaccine.47–49 Cost is also cited as a common barrier to completion of the hepatitis B vaccine series. In some states, such as Massachusetts, state funds are available to pay for hepatitis B vaccine provided to high-risk contacts.

Polio

Endemic transmission of polio no longer occurs in the US, though a recent outbreak in an unimmunized community emphasizes the importance of maintaining high vaccine coverage.50 Because oral polio vaccines remain in use in many parts of the world, vaccine strains of virus will continue to enter the US because of shedding of virus for a period of time following oral administration of vaccine. There is also the possibility of importation of wild-type strains of poliovirus by those arriving from areas that continue to have endemic wild-type disease. Outside the international adoption literature, there are few serosurveys of immigrant protection against polio in US immigrants, though serosurveys have been done of Kosovar children resettling in Italy and immigrant workers in Israel (see Table 13.1).23,40,51 Many countries, however, participate in polio eradication campaigns, and immigrants are likely to have received immunization against polio. Foreign-born children between 19 and 35 months of age were as likely as US-born children to have received three or more doses of poliovirus vaccine.10 All immigrants should receive a primary series of three doses of vaccine, with a booster in adulthood if traveling to an area of endemic polio.

Hepatitis A

Immigrants may be candidates for hepatitis A vaccine either because they resettle in an area where this vaccine is recommended, they have another health problem such as hepatitis B infection for which hepatitis A vaccine is recommended, or they meet other criteria for which hepatitis A vaccine is recommended. In the prevaccine-era in the US (before 1995), serologic evidence of hepatitis A varied by age and ethnicity: prevalence was 9% in those 6–11 years, 19% for those 20–29 years, 33% for those 40–49 years, and 75% in those > 70 years of age. Prevalence was highest among Mexican Americans (70%) compared with non-Hispanic blacks (39%) and non-Hispanic whites (23%).52 Since the late 1990s, hepatitis A rates have declined more rapidly in children than adults, and have become similar in all age groups. Racial/ethnic differences in rates have narrowed, but rates remain higher in Hispanics than non-Hispanics.52a Immigrants, especially those born and raised in developing countries, are likely to have been infected in childhood and are more likely to be immune to hepatitis A than US-born individuals. Seroprevalence studies of immunity to hepatitis A show that many immigrants are immune to hepatitis A: 87% of 1392 recently arrived adult immigrants to Canada had evidence of hepatitis A antibody.24 Two studies of hepatitis immunity in adult patients seen for pre-travel consultation documented presence of antibody in 95% (Boston) and 80% (Honolulu) of those tested.53,54 Cost-effectiveness studies show consistently that testing for hepatitis A antibody before initiating the two-dose vaccine series is cost-effective when prevalence of antibody to hepatitis A exceeds about 30%, a value exceeded in many immigrant groups.54–56

In 1999, the Immunization Practices Advisory Committee (ACIP) expanded recommendations for hepatitis A vaccination in the US to include routine immunization of children in states, counties, and communities with rates of infection > 20 cases per 100 000 population, and considering immunization in areas where rates were between 10 and 20 cases per 100 000 population.52 In 2005, the ACIP voted to recommend universal immunization of children 12–23 months of age with hepatitis A vaccine.57 All hepatitis A vaccines now available in the US are licensed for use beginning at 1 year of age.

Most immigrants, therefore, are likely to be at lower risk of hepatitis A in the US than they were in their country of origin, with the exception of those arriving from countries with lower rates of hepatitis A than the US. Special attention, however, needs to be paid to a few categories of immigrants, or of those who have close contact with immigrants, in order to provide optimal protection. First, children of migrant workers, especially those living along the US–Mexico border who travel frequently to their parents’ country of origin, are at increased risk of hepatitis A.58 A position paper prepared by the Migrant Clinician’s Network outlines recommended strategies for addressing risk of hepatitis A in migrant health workers and their families.59 Second, families who adopt children from overseas may be at increased risk of hepatitis A. Hepatitis A has been transmitted from an internationally adopted child to a family member.60 Clinicians caring for internationally adopted children and their families may want to offer protection against hepatitis A as well as other vaccine-preventable diseases before the adoption.61,62 Lastly, the youngest immigrants as well as children of immigrants who have never visited their parents’ countries of origin may be at increased risk of hepatitis A when they return to visit relatives and friends.63 Clinicians caring for immigrant families may want to maintain awareness of travel plans and be prepared to offer appropriate vaccines at this time (see Ch. 58; Visiting Friends and Relatives).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree