IDENTIFIABLE CAUSES OF MALE INFERTILITY

Part of “CHAPTER 118 – MALE INFERTILITY“

A variety of factors have been identified that can impair sperm production and cause infertility. Many of these are associated with reduced Leydig cell function and may present as hypogonadism rather than infertility (see Chap. 115). This section reviews the major causes of infertility based on pathophysiology.

HORMONAL DISORDERS

Several hormonal disorders are associated with testicular dysfunction. The most common of these is gonadotropin deficiency, either congenital, as in idiopathic hypogonadotropic hypogonadism (IHH, Kallmann syndrome) in which there is a failure of GnRH secretion, adult-onset IHH, or acquired, as by a mass or infiltrative lesion interfering with pituitary or hypothalamic function and normal gonadotropin stimulation of the testes.37,38 These patients may present with loss of libido and impotence and usually have small or soft testes and an inadequate or absent ejaculate. The hormone profile shows low serum gonadotropins and a low testosterone. A similar clinical picture is produced by hyperprolactinemia because excess prolactin depresses GnRH secretion.34 Prolactin levels two to three times the upper limits of normal are usually associated with impaired testicular function and impotence, while the effects of slight elevations are unclear. So far, gonadotropin-receptor defects, as for FSH, have not been demonstrated to be a cause of hypogonadism.39

Patients with hypogonadotropic hypogonadism respond well to therapy, with many becoming fertile. Intramuscular gonadotropins (human chorionic gonadotropin [hCG], human menopausal gonadotropin [hMG], recombinant FSH [rFSH]) directly stimulate the testis to produce testosterone and sperm. These are usually administered as hCG alone, 1200 to 2000 IU given intramuscularly thrice weekly, or with hMG or rFSH, 37.5 to 75.0 IU given intramuscularly thrice weekly.32 Normal testosterone production is achieved in >90% of cases, while sperm production depends on testicular size. Men with testicular volumes >4 mL produce sperm and are fertile in ˜80% of cases, while those with initial gonadal volumes of <4 mL become fertile in fewer than half of cases and require combination therapy (hCG plus hMG or rFSH). Alternatively, pulsatile GnRH can be administered by a pump and can stimulate pituitary gonadotropin release, although response rates seem similar.37

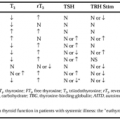

Subtle forms of androgen resistance also may exist in which the presentation is infertility with azoospermia, although this was not duplicated in a separate study.40,41 Subsequent studies of the androgen receptor transactivation domain have shown that point mutation polymorphisms do not affect sperm production, but long polyglutamic tracts can.42,43 Hyperthyroidism is associated with elevated sex hormone—binding globulin, altering the ratio of free testosterone to free estradiol.44 In severe cases, this can cause gynecomastia and reduced sperm output. Hypothyroidism may be associated with a reversible hypogonadism.44a Hypercortisolism can be associated with depressed testicular function, probably by suppression of the hypothalamic-pituitary axis.45

CHROMOSOMAL ABNORMALITIES

Certain specific chromosomal abnormalities are associated with impaired testicular function. Klinefelter syndrome (47,XXY) is the most common of these (see Chap. 115). The classic form—small firm testes, inadequate virilization, gynecomastia, and azoospermia—is relatively easy to recognize. However, patients can present with impaired sperm production and azoospermia but with adequate androgen levels inducing normal virilization, libido, and potency.46,47 This is especially true of mosaic forms (e.g., 46,XY/47,XXY). In mosaics, the testes are small, and serum gonadotropins usually are elevated, but the spectrum can extend to near normal values. A karyotype should be considered in men with reduced testicular size and azoospermia to rule out Klinefelter syndrome or a variant.

Another disorder of sex chromosome number is the XYY syndrome (47,XYY), in which there is an extra Y chromosome. Typically, these men have normal virilization and normal serum gonadotropins and testosterone but show variable tubular abnormalities (from maturation arrest to tubular sclerosis) and have severe oligospermia or azoospermia.48,49 Autosomal chromosome abnormalities can be associated with testicular dysfunction, notably Down syndrome (trisomy 21) and balanced autosomal translocations.50 Specific causes of nonmotile sperm (necrospermia) have been identified that are associated with infertility. One form of nonmotile sperm is caused by a lack of dynein arms in the microtubule filaments forming the sperm tail (Kartagener syndrome: includes sinusitis, bronchiectasis, and situs inversus).51 Another form of necrospermia is caused by a deficiency of a specific metabolic enzyme, protein—carboxyl methylase, resulting in a metabolic basis for the loss of motility.52

Several groups have demonstrated the presence of microdeletions in the Y chromosome, some of which are associated with infertility.53,54 These may account for 10% to 15% of cases of “idiopathic infertility.” As these microdeletions can be transmitted by IVF-ICSI, consideration for genetic screening and counseling should be given to men who are candidates for these procedures.55

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree