Hyperthermia as a Treatment Modality

The rationale for combining hyperthermia (HT) with radiation (RT) rests on several mechanisms. HT is known to cause direct cytotoxicity and also acts as a radiosensitizer. Studies performed in vitro yield a pattern of survival curves similar to RT survival curves. The mechanisms of action of HT appear to be complementary to the effects of RT with regard to inhibition of potentially lethal damage and sublethal damage repair, cell cycle sensitivity, and effects of hypoxia and nutrient deprivation. In addition, HT has effects on blood flow and tumor physiology, which may be of particular interest with regard to tumor oxygenation and combination therapy with drug-carrying nanoparticles.

Implementation of HT in the clinic presents significant challenges. It is difficult to heat tumor tissue volumes with uniformity and precision. There is no standardized equipment to effect locoregional HT. Techniques for measuring temperature and the actual definition and calculation of thermal dose remain significant problems.

The biologic rationale for HT is compelling and is founded on principles of classic radiobiology, molecular biology, and tumor physiology. Further improvements in technologies to deliver HT and measure thermal dose remain crucial. Nonetheless, there are now 17 randomized trials of HT in human cancer patients, the majority of which demonstrate a local control and/or survival advantage with the addition of HT to standard therapy, providing strong impetus for continuing work in this field.

THE BIOLOGY OF HYPERTHERMIA

THE BIOLOGY OF HYPERTHERMIA

Definition of Hyperthermia

HT means elevation of temperature to a supraphysiologic level. When cells or tumor tissues are subjected to elevated temperatures, a number of events follow that have important biologic consequences for cancer therapy. HT can kill cells in its own right, but perhaps more important, it can sensitize tumor cells to other forms of therapy, including RT and chemotherapy (CT). Some of the physiologic consequences of HT have implications for radiotherapy as well, such as thermally induced reoxygenation. Changes induced in microvessel pore size can lead to increased delivery of nanoparticle drugs1,2,3,4 as well as macromolecular therapeutic agents, such as monoclonal antibodies5 or drug-carrying polymers.6 The adaptive response to hyperthermic exposure (thermotolerance) may augment host immune responses against tumor cells.7 This chapter will not deal directly with the use of whole-body HT and will discuss the emerging field of thermal ablation only briefly8 since neither has been combined with RT in the clinic.

Effects of Hyperthermia Alone on Cell Survival

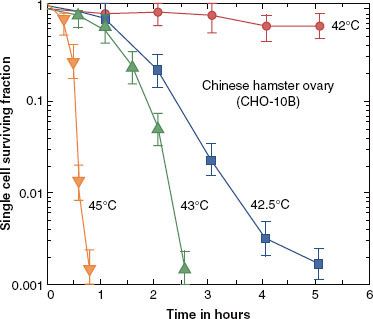

HT kills cells in a log-linear fashion, depending on the time at a defined temperature (Fig. 31.1). Resulting survival curves typically have an initial shoulder region, followed by an exponential portion. The initial shoulder region indicates that damage has to accumulate to a certain level before cells begin to die, analogous to the sublethal damage that is seen with ionizing radiation. At lower temperatures, a resistant tail may appear at the end of the heating period. This resistant tail is not a resistant subpopulation, as might be seen for RT when there is a hypoxic subfraction, but rather is due to the induction of thermotolerance, which develops during the heating period. At temperatures >43°C the tail does not develop because thermotolerance is not observed at temperatures greater than this. More details on the mechanism of thermotolerance and its potential clinical significance are discussed later.

FIGURE 31.1. Cell survival curves for the Chinese hamster ovary cell line, plotted as a log of surviving fraction as a function of time of heating at a defined temperature. Note that the rate of cell killing is highly temperature dependent. For example, 5 hours of heating at 42°C kills very few cells, whereas 5 hours of heating at 0.5°C higher (42.5°C) results in nearly three logs of cell killing. (From Roizin-Towle L, Pirro JP. The response of human and rodent cells to hyperthermia. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1991;20:751–756; with permission from Elsevier.)

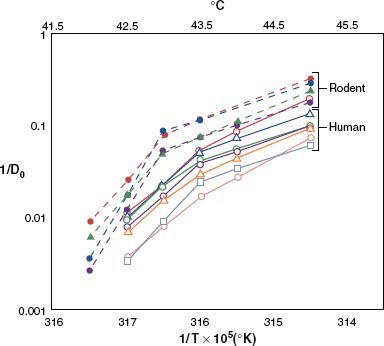

FIGURE 31.2. Arrhenius plots for a variety of rodent and human tumor cell lines, as assessed in vitro. Note that all human cells are below and to the right of the rodent cell lines. This means that for a given temperature, the slope of the cell-killing curve is less steep for human than for rodent cells. In addition, the breakpoint of the Arrhenius plot appears to be about 0.5°C higher for human than for rodent cells. These observations mean that human cells are more thermally resistant than rodent cells.198 (From Roizin-Towle L, Pirro JP. The response of human and rodent cells to hyperthermia. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1991;20:751–756; with permission from Elsevier.)

Thermal Isoeffect Dose: The Arrhenius Relationship

The temperature dependence of the rate of cell killing by heat is referred to as the Arrhenius relationship. Typically, one plots the log of the slope (1/Do) of cell survival curves as a function of temperature (Fig. 31.2). Characteristically, Arrhenius plots have a biphasic curve; the point at which the slope changes is referred to as a breakpoint. Above the breakpoint for nearly all cell types, a change in temperature of 1°C will double the rate of cell killing. Below the breakpoint, the rate of cell killing drops by a factor of 4 to 8 for every drop in temperature of 1°C. The change in slope below the breakpoint is due to the development of thermotolerance during heating.

The recognition that there is a definable relationship between the rate of cell killing and temperature led Sapareto and Dewey9 to propose using this relationship to normalize thermal data from HT. HT results in temperatures within tumors that are almost always nonuniform, with variable time–temperature history. The formulation for this relationship is as follows:

where CEM 43°C is the cumulative equivalent minutes at 43°C (the temperature suggested for normalization), t is the time of treatment, T is the average temperature during the interval of heating, and R is a constant. When above the breakpoint, which is usually assumed to be 43°C, R = 0.5. When below the breakpoint, R = 0.25.

For a complex time–temperature history, the heating profile is broken into intervals of time (t) where the temperature remains relatively constant. CEM 43°C is calculated using the average T (Tavg) for each interval, and the resultant data are summed to give a final CEM 43°C for the entire heating regimen:

The CEM 43°C (thermal isoeffect dose) formulation has been used extensively and successfully in clinical trials to describe thermal dose despite its derivation from rodent studies.

Mechanisms of Hyperthermic Cytotoxicity

Cellular and Tissue Responses to Hyperthermia:

Targets for Hyperthermic Cytotoxicity

The predominant molecular target for hyperthermic cell killing appears to be protein.10 For many cells and tissues (both tumor and normal), the heat of inactivation for cell killing is in the range of that necessary for protein denaturation (130 to 170 kcal/mole). Additional evidence for proteins being the primary target is the importance of heat shock proteins in protecting cells from thermal damage. When cells are exposed to heat, the synthesis of nearly all proteins is stopped, with the exception of heat shock proteins, the synthesis of which is upregulated.11 One of the primary functions of heat shock proteins is to refold other proteins that have been denatured or damaged.12

Some cellular organelles are especially important in controlling the thermal response. For example, modification of cellular membrane lipid content or use of membrane-active agents such as alcohols can sensitize cells to heat killing, but the sensitization is probably related to destabilization of the membrane as it relates to lipid–protein interactions.10 The cytoskeleton of cells is particularly heat sensitive.13 Cytoskeletal collapse also disrupts cytoskeletal-dependent signal transduction pathways.14,15 Enzymes in the respiratory chain are more heat sensitive than enzymes in the glycolytic pathway.16 The heat sensitivity of the centriole leads to chromosomal aberrations following thermal injury.17 Finally, many DNA-repair proteins are heat sensitive. This may be one of the mechanisms that lead to heat-induced radiosensitization and chemosensitization.18,19

Little information is available from human tumors to know what proportion of cells is killed with heat alone or what the underlying mechanisms of cell death might be. Such information may be important with respect to reoxygenation, which has been seen in rodent, canine, and human tumors20 after HT. Induction of apoptosis could lead to reoxygenation following heating as a result of reduced oxygen consumption, which could in turn increase RT sensitivity. Alternatively, induction of necrosis is not likely to affect hypoxia since both vessels and tumor cells would be killed in the process.

Thermotolerance

Thermotolerance is defined as a transient adaptation to thermal stress that renders surviving heated cells more resistant to additional heat stress. Whether or not a cell dies as a result of thermal insult is dependent on the net balance between how much protein is damaged and how much is protected and repaired via thermotolerance. Thermotolerance can develop either during or after heat stress and can persist for several days. If cells are not exposed to thermal stress again, thermotolerance will decay. The time of peak thermal resistance and the time of decay are related to the severity of the heat shock.

Concerns over the persistence of thermotolerance after HT has affected the design of many clinical trials of thermoradiotherapy. In most trials, a minimum of 48 hours has been suggested between HT fractions in order to avoid re-treatment during thermotolerance. This concern has proscribed the use of daily HT in conjunction with daily radiotherapy in most clinical trials or alternatively led to the use of hypofractionated RT, for example, large fractions twice weekly with concurrent heat.

Some investigators have suggested that one should take advantage of heat radiosensitization rather than hyperthermic cytotoxicity and ignore the issue of thermotolerance. The degree of HT-mediated cytotoxicity may be low with HT as it is currently practiced because temperatures achieved are largely below that needed for direct cell killing. Furthermore, heat radiosensitization is relatively unaffected by thermotolerance.21

Does thermotolerance occur in humans after heating? Heat shock protein synthesis was evaluated in a small group of human patients (n = 23) with chest wall recurrences of breast cancer who underwent RT with or without HT. Elevated levels of heat shock proteins in biopsy specimens after treatment correlated with lower probability of attaining a complete response.22 In another study of patients treated with fluorouracil (5-FU) plus thermoradiotherapy for colorectal cancer, no correlation between HSP27 or HSP70 levels, either before or after treatment, and outcome was seen.23 Interpretation of clinical studies is complicated by the fact that heat shock protein expression is frequently upregulated in tumors in the absence of heat stress.11 Stresses other than HT, such as hypoxia and hypoxia–reoxygenation injury, can cause elevations in heat shock protein levels. Thus the question of the relevance of thermotolerance to the clinic and the best HT/RT fractionation scheme remains unsettled.

Immunologic Implications of the Heat Shock Response

There is emerging evidence that HT can augment the immunologic response toward tumors. Examples of effects that are known to occur after heating include (a) increased immunogenicity,24–27 (b) increased T-cell, NK-cell, and dendritic cell maturation and activity,28–34 and (c) enhanced trafficking of immune effector cells into tumors and lymphatic organs.35,36 The trafficking is likely mediated by cytokines such as interleukin 6.37,38

Hyperthermia and Physiology

In this section, we discuss what is known about the physiologic consequences of HT and then discuss how physiology can be manipulated to enhance the efficacy of HT.

As temperatures are elevated, tissue perfusion increases. In muscle, cyclic variations in temperature have been observed when delivered power is kept constant, demonstrating that thermoregulation is controlled by a threshold temperature.39 The temperature threshold for this change is 41°C to 41.5°C in skin.40 Changes in vascular permeability also occur, leading to edema formation in the heated volume. As temperature or time-at-temperature is increased, vascular stasis and hemorrhage develop.

The change in normal tissue perfusion upon heating is typically much greater than what one sees in tumors. Muscle and skin perfusion increase by about 10-fold, whereas tumor perfusion may increase by 1.5- to 2-fold.41 The mechanism of vascular stasis in tumors is not fully determined, but potential sources include arteriovenous shunting, thrombus formation, and leukocyte plugging.42 Hemorrhage probably occurs as a result of enlarged endothelial cell gaps or loss of endothelial cell and basement membrane integrity along the vessel wall.

These vascular effects may be exploited clinically. HT causes extravasation of nanoparticles into tumor parenchyma. Heating to 40°C to 42°C results in a marked increase in extravasation of liposomes in tumor but not in normal tissue vasculature. Above 42°C vascular stasis and hemorrhage occur with reduced liposomal extravasation. These results are consistent with the hypothesis that the increase in extravasation is due to cytoskeletal collapse in the vessel wall (endothelial cell). The increase in liposomal extravasation can be exploited as a drug delivery vehicle, particularly since the effect appears to be preferential to tumors. Many investigators have shown that HT increases liposomal drug accumulation in tumors, leading to enhanced antitumor efficacy of a variety of drugs compared with liposome administration alone or free drug administered with HT.4 When temperature-sensitive liposomes are used, even better antitumor effects can be achieved, particularly using low-temperature–sensitive liposomes that have entered into human clinical trials.1,43,44 The improved effectiveness of these drugs when combined with HT is directly related to the increase in drug delivery.1,45,46

Although the changes in perfusion in tumors are relatively small in comparison with normal tissues, there have been a number of efforts to exploit them as a means to augment drug delivery to tumors. For relatively small agents, such as most chemotherapeutic drugs, there is no real advantage to using heat to augment delivery, although increased cellular uptake has been seen with a number of drugs.47 For drugs with molecular weight <1,000, the primary mechanism that governs drug transport is diffusion, which is controlled by the concentration gradient across the vascular wall.48 The temperature dependence of diffusion is not large, so HT has relatively little effect.

However, convection is the primary driving force for transvascular transport for molecules >1,000 molecular weight. This is controlled by the pressure gradient across the blood vessel wall. HT increases transvascular delivery of monoclonal antibodies5 and polymeric peptides that can carry drugs or radioisotopes.6

Effects of Hyperthermia on Tumor Metabolism and Oxygenation

Enzymes for aerobic metabolism are more heat sensitive than those involved in anaerobic metabolism.16 The net result of this difference in heat sensitivity is that nutrient stores are more rapidly depleted during heat shock, leading to a reduction in adenosine triphosphate (ATP) and buildup of lactic acid. A number of rodent studies have demonstrated changes in energy balance and pH after heating. Kelleher et al.49 reported decreases in ATP and increases in lactate concentration occurring concomitantly with reduction in tumor blood flow after heating. In a series of human patients with soft tissue sarcomas who were treated preoperatively with HT and RT, a reduction in magnetic resonance spectroscopy ATP/inorganic phosphate was significantly correlated with a higher probability for tumor response.50 HT reduces oxygen consumption rates in murine and human tumor lines.51 These results are consistent with the theory that a reduction in tumor respiration occurs after HT.

A shift toward anaerobic metabolism would decrease oxygen consumption rates, which could improve tumor oxygenation. Oleson52 suggested that some of the benefits of HT in the clinical setting may result from improvements in oxygenation. Results from several studies in rodent tumors and human tumor xenografts support the notion that an overall improvement in tumor oxygenation can result from time–temperature combinations below those that cause vascular damage (e.g., 41°C to 41.5°C for 60 minutes). Higher thermal doses that cause vascular damage (e.g., >43°C, 60 minutes) may lead to decreases in tumor oxygenation.20

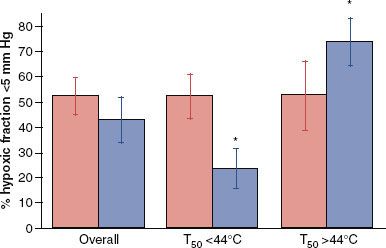

HT improves tumor oxygenation in canine and human tumors.53–55 In a human study of soft tissue sarcomas, failure to reoxygenate after the first HT fraction led to a significantly lower probability of achieving pathologic complete response at the time of surgery.54 In women with locally advanced breast cancer treated with neoadjuvant thermochemoradiotherapy, reoxygenation after the first heat treatment was associated with higher likelihood for achieving a clinical response.56 In a canine soft tissue sarcoma study involving thermoradiotherapy treatment, there was an overall improvement in partial pressure of oxygen at 24 hours after the first heat treatment, but for those tumors in which the median temperature was greater than 44°C, perfusion and tumor oxygenation decreased (Fig. 31.3). This threshold temperature for vascular damage is about 44°C for human and canine tumors. It is difficult, however, to attain this temperature in nonanesthetized human patients.

Zywietz et al.57 reported that twice-weekly heating to 43°C for 60 minutes in combination with 60 Gy delivered in 20 fractions over 4 weeks resulted in a steady decline in partial pressure of oxygen of a rat rhabdomyosarcoma. However, Thrall et al. reported that there were long-term improvements in oxygenation of canine tumors treated with fractionated thermoradiotherapy.53 Thus, it is not known with certainty whether reoxygenation or deoxygenation predominates after fractionated thermoradiotherapy and how this relates to treatment outcome. The sarcoma and breast clinical studies cited previously argue in favor of a positive effect on oxygen status, but only a few HT treatments may be necessary to achieve this.

It has been reported that fractionated HT (42.5°C for 60-minute conditioning dose followed by 44.5°C for up to 90 minutes) can lead to vascular thermotolerance.58 This means that the likelihood of vascular damage decreases if a second HT treatment is given within 1 to 2 days after the first treatment, at a time when thermotolerance may still be present. It was reported that vascular thermotolerance is associated with vessel normalization.59 Normalization is a phenomenon popularized by Jain to explain the beneficial effects of antiangiogenic treatments to improve transport properties of tumors.60 It is associated with a decrease in microvessel density and an increase in pericyte coverage, conditions reflective of a more mature vasculature.

The process of vascular normalization after heating may be mediated in part by upregulation of the transcription factor hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (HIF-1). This transcription factor is known to regulate angiogenesis by controlling levels of vascular endothelial growth factor in tissue. Moon et al. reported that HT increases HIF-1 in tumors by activating the enzyme NADPH oxidase.51 The reactive oxygen species produced by this enzyme inhibited degradation of the labile subunit of HIF-1, HIF-1α.51 The upregulation of HIF-1 levels was accompanied by increases in levels of vascular endothelial growth factor and perfused vascular density in heated tumors.

FIGURE 31.3. Effects of median temperature during hyperthermia treatment on oxygenation of canine tumors, as measured 24 hours postheating. When the median temperature is less than 44°C, there is significant reduction in hypoxic fraction. When median temperature exceeds 44°C, hypoxic fraction increases. Closed bar indicates measurements taken before hyperthermia, and open bar indicates measurements taken 24 hours after hyperthermia treatment. (Data replotted from Vujaskovic Z, Poulson J, Gaskin A, et al. Temperature-dependent changes in physiologic parameters of spontaneous canine soft tissue sarcomas after combined radiotherapy and hyperthermia. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2000;46(1):179–185; with permission from Elsevier.)

Physiologic Approaches to Enhance Thermal Cytotoxicity: pH Modification

It is well established that an acute reduction in extracellular pH can greatly enhance sensitivity to HT. Cells adapted to grow at low pH, as occurs in tumors, have little reserve to further increase proton pumping. It is the reduction in intracellular pH that is actually responsible for the increase in cytotoxicity.61 The potential degree of enhancement in killing is substantial, and, as a result, considerable effort has been made to accomplish this feat in vivo. The most widely studied method has been induction of hyperglycemia. The rationale is that excess glucose load to the tumor will push it toward glycolysis and lactic acid production because most tumors have a limited oxygen supply and also have defects in respiratory pathways. Induction of a hyperglycemic state may also reduce blood flow by increasing blood viscosity. Reduced perfusion compromises heat exchange capacity, thereby increasing temperatures in tumor during heating. When glucose has been administered intravenously, there has been little effect on perfusion, but reduction in extracellular pH has been observed.62,63

In humans, the induction of hyperglycemia has been accomplished by either oral or intravenous glucose administration. Results using this approach have been mixed. On average, the drop in extracellular pH is about 0.17 pH unit, which is near the goal of 0.2 pH unit.62 However, there is considerable variation from one patient to another in terms of how effective this approach is. Furthermore, in prediabetic patients, the trend is toward an increase in pH rather than a decrease. In canines with soft tissue sarcomas, induction of hyperglycemia via intravenous administration did not result in any significant change in either intracellular or extracellular pH.64

The use of hyperglycemia resulted in improved response to thermochemotherapy and thermoradiotherapy in rodents.65,66 Data in human tumors are sparse. One study in a limited number of patients suggested improvement in response with the use of hyperglycemia combined with thermoradiotherapy.67 However, pH was not measured, and the study was not randomized.

The addition of agents that can selectively drive down tumor intracellular pH, such as glucose combined with the respiratory inhibitor metaiodobenzylguanidine, has the potential to further enhance hyperthermic cytotoxicity selectively in tumor tissues.68,69 Some groups have also focused on the use of pharmacologic agents that block the extrusion of hydrogen ions from cells, which is normally accomplished via membrane-bound pumps. Use of such agents, in combination with acidification of the extracellular space, can lead to enhanced hyperthermic cell killing both in vitro and in vivo.70

Blood Flow Manipulation

Blood perfusion is a major impediment to effective heating. This is because perfusion is the primary mechanism for conducting heat and maintaining homeostasis. Thus, if tumor blood flow can be effectively reduced, temperatures in the tumor will increase. A number of vasoactive agents have been shown to reduce tumor blood flow, including some that are normally considered to be vasodilators. Agents investigated include hydralazine, nitroprusside, and angiotensin II; the first two drugs are vasodilators and the last is a vasoconstrictor. Clinically, changes in blood pressure have limited doses that can be safely used, minimizing effects on tumor blood flow. New agents are needed. It also makes sense to consider combinations of approaches that might reduce both tumor blood flow and pH and lead to improved temperature distributions, as well as to heat sensitization.

Radiation and Hyperthermia

Rationale for Combining Hyperthermia with Radiotherapy

When RT is combined with HT, complementary effects occur. Cells in the S phase of the cell cycle are relatively radioresistant, but when heated, these cells are most sensitive. Hypoxic cells are known to be three times more resistant to RT as compared with aerobic cells. With HT, there is no difference in sensitivity between aerobic and hypoxic cells. As discussed in detail earlier, there is good evidence that HT can lead to reoxygenation, which will further improve RT response.20,54,55 Finally, HT inhibits the repair of both sublethal and potentially lethal damage via its effects in inactivating crucial DNA repair pathways.71–73

Factors to Consider When Combining Hyperthermia with Radiotherapy

The interaction between RT and HT is described by the “thermal enhancement ratio” (TER), defined as the ratio of doses of RT to achieve an isoeffect for RT/RT + HT. TERs for local control have been estimated for a number of human tumors using historical control data for RT alone.74 In most tumor types examined, these ratios were greater than 1. Assessment of normal tissue TER has not been attempted, except in a few cases. For those examples, TER values for normal-tissue damage have been less than those for tumor in the same patient population, suggesting potential for therapeutic gain for RT+ HT compared with RT alone.74 Prospective, randomized trials in dogs with spontaneous tumors have also shown evidence for improved local tumor control with RT + HT compared with RT alone,75–76,77–78 with no observable increase in the frequency of clinically relevant late normal-tissue complications. In one canine trial, enhancement of late RT damage (as assessed histologically) was reported and the duration of acute RT complications was prolonged.78 There is evidence, however, that excessively high intratumoral temperatures (i.e., >45°C for 60 minutes) can lead to damage to surrounding normal tissues, an effect that is often caused by rapid tumor regression.76,79 Such damage is not easily repaired and can lead to chronic tissue consequences, such as fibrosis, fistula formation, and bone necrosis.

In summary, most available data from preclinical and clinical studies indicate that therapeutic gain is achievable for the combination of HT with RT. There is little evidence to suggest that HT enhances the incidence or severity of late normal-tissue complications from RT, particularly when excessively high intratumoral temperatures are avoided.

Hyperthermia and Chemotherapy

Rationale for Using Hyperthermia with Chemotherapy

Many chemotherapeutic agents have demonstrated synergism with HT, including cisplatin and related compounds, melphalan, cyclophosphamide, nitrogen mustards, anthracyclines, nitrosoureas, bleomycin, mitomycin C, and hypoxic cell sensitizers.80 The mechanisms may include (a) increased cellular uptake of drug, (b) increased oxygen free radical production, and (c) increased DNA damage and inhibition of repair.47 Hypoxia and pH appear to be important in the thermochemotherapeutic response.

An important factor in the potential use of HT with many drugs is its ability to reverse, at least partially, drug resistance. Examples of drugs for which this has been shown include cisplatin,81,82 melphalan,83 nitrosoureas,84 and doxorubicin, when combined with the MDR inhibitor verapamil.85

In vitro and in vivo results may not correlate. Paclitaxel, for example, shows little in vitro activity, but clinical results in combination with HT and RT have been encouraging.56

Most antimetabolites do not interact with HT synergistically when given concomitantly.47 However, it is important to consider issues such as time of drug exposure and temperature, both of which may be important in determining where and when to expect a positive interaction. When 5-FU has been given simultaneously with HT, there have been only additive effects.86 However, 5-FU has been shown to interact supra-additively with HT under specific conditions. Heating to 39°C to 41°C can lead to enhanced conversion to active metabolites, thereby increasing drug cytotoxicity. In addition, continuous-infusion protocols with this drug may lead to cell cycle block in S phase, a relatively sensitive part of the cell cycle to HT.87

For most drugs (excluding 5-FU and perhaps other antimetabolites), the optimal sequence between heat and drug is to administer them simultaneously or to give the drug immediately before the onset of heating. For platinum-containing drugs, the tissue extraction rate of drug may be increased with HT, further substantiating the rationale for use of this sequence.88 The degree of interaction between drugs and HT is temperature and cell line dependent.47

There are also some classes of drugs for which there has been no demonstrated synergistic interaction. Interactions with etoposide have been unpredictable, and current recommendations are that one cannot expect synergistic interactions with it.47 There is also no evidence for synergistic interaction between vinca alkaloids and HT.

The term trimodality therapy has been used to describe combination therapy of HT, drugs, and RT. It has been studied in both preclinical and clinical models and will be discussed at length in the clinical section of this chapter.

Hyperthermia and Thermosensitive Liposomally Encapsulated Drugs

In a classic paper, Yatvin et al.89 suggested that a temperature-sensitive liposome could be used to selectively deliver drug to tumors. Several papers have been published using formulations similar to that of Yatvin et al. The combination of HT with such drug carriers increased drug delivery and efficacy as compared with using drug carrier alone or free drug with HT.4 However, the thermal properties of the original Yatvin formulation were not amenable to clinical application. The release temperature was too high, and the rate of drug release was relatively slow.90 A breakthrough occurred when Needham et al.91 reported the formulation for a low-temperature-sensitive liposome that rapidly released drug at 41.4°C. A second formulation with similar drug release properties was reported by Lindner et al.92 This type of liposome is referred to as a low-temperature-sensitive liposome (LTSL).

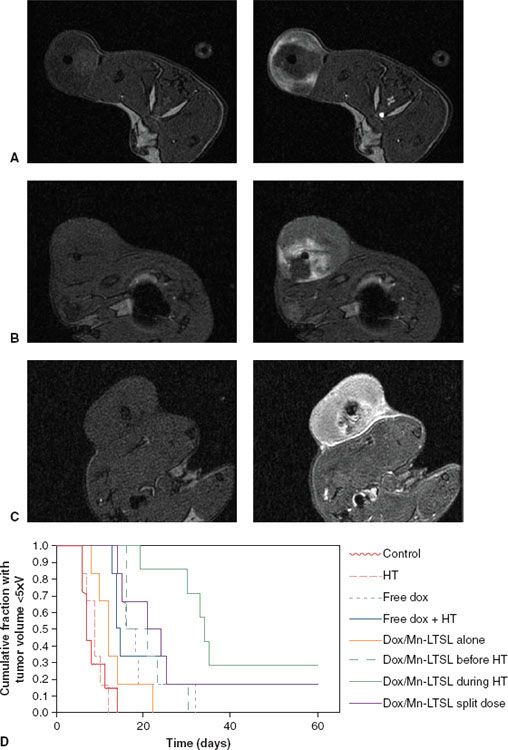

Direct comparison of the relative efficacy of a doxorubicin-containing LTSL, the Yatvin formulation, a traditional non–thermally sensitive liposome formulation similar to Doxil, and free drug has been made. The LTSL was clearly more effective than any other formulation, as assessed using tumor growth delay as an endpoint. The difference in effectiveness was demonstrated to be related to a significant improvement in drug delivery to tumor, as well as to increased drug binding to DNA.1 Further preclinical work with this formulation demonstrated that it has broad activity when combined with local HT across a range of different tumor types.93 The formulation was tested in a phase I trial of canine tumors, where the maximum tolerated dose was associated with bone marrow toxicity.94 This has been the dose-limiting feature of the toxicity in phase I trials in humans as well.43,44 The drug was tested in a double-blind, phase III trial in combination with thermal ablation for hepatocellular carcinoma (104-06-301, NCT00617981). The trial is now completed, and the sponsor is waiting for follow-up before reporting the results. The formulation has also been used as a magnetic resonance (MR) imaging agent, where drug and contents have been loaded in the same liposome.45,46 Changes in MR signal intensity were used to determine drug concentration in preclinical models. Concentrations measured with MRI were associated with antitumor activity in individual animals45 (Fig. 13.4).

FIGURE 31.4. Tumor drug distributions and antitumor effect following various low-temperature-sensitive liposome (LTSL) and hyperthermia treatment protocols. Rats bearing fibrosarcomas were treated with doxorubicin- and manganese-containing LTSLs during hyperthermia (A), prior to hyperthermia (B), or in two equal doses, one prior to hyperthermia and the other after steady-state hyperthermia had been reached (C). Tumors are shown prior to treatment (Before) and after LTSL and hyperthermia treatment (After). Liposome content release corresponds to the white regions. The corresponding antitumor effect is also depicted (D). Treatment A resulted in peripheral enhancement at the edge of the tumor, whereas the split-dose treatment (C) led to uniform enhancement. Treatment B resulted in central enhancement, as well as delayed tumor growth. (A to C, unpublished data; D, from Ponce AM, Viglianti BL, Yu D, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of temperature-sensitive liposome release: drug dose painting and antitumor effects. J Natl Cancer Inst 2007;99(1):53–63; Oxford University Press, with permission.)

HYPERTHERMIA PHYSICS

HYPERTHERMIA PHYSICS

The objective of local or regional hyperthermia therapy is to achieve tumor temperatures in the range of 40°C to 45°C and to maintain that temperature for a time period on the order of 1 hour. Attaining this thermal dose goal throughout a tumor volume requires the delivery of power with sufficient spatial and temporal variation to balance the heterogeneous and time-varying heat transfer processes within the target volume. Heat transfer from thermal conduction and blood perfusion redistribution of energy within living tissue are complex, and achieving the desired thermal uniformity across large tissue regions is difficult. Thermal conduction is a well-understood process, but in practical delivery of clinical hyperthermia the thermal conductivity is complicated by the irregularities of patient anatomy and tissue interfaces and varies by more than factor of two between high-water-content tissues and fat or bone. An even larger uncertainty in heat transfer is caused by blood perfusion, which varies dramatically among tissue types, and as a function of time and local temperature. Even with excellent control of the power deposition, knowledge of tissue thermal properties is needed in order to preplan temperature uniformity within a given target volume. In addition, since blood flow changes rapidly, temperature should be measured continuously during treatment in order to readjust the heating pattern for uniform temperature.

Clinical hyperthermia can be accomplished using one of three modalities: thermal conduction (e.g., circulating hot water in a needle, a catheter, or a surface pad), nonionizing electromagnetic radiation (EM), or ultrasound (US). In each case, heating is sensitive to tissue geometry, heterogeneity of tissue properties (especially blood perfusion), and issues with coupling energy into tissue from practical-sized applicators. Because of the limited penetration of heat from a hot source, thermal conduction heating is largely restricted to interstitial applications with closely spaced implant arrays. Energy can be delivered deeper into tissue using EM or US fields that deposit energy directly in tissue, with effective penetration dependent on frequency and applicator type. For either source, the absorbed power distribution is commonly normalized by the respective tissue density and referred to as the specific absorption rate (SAR) distribution, with units of watts per kilogram. The underlying physical principles are described in several excellent review articles95–96,97–99,100 and in books that cover the field of hyperthermia.101–102,103 Representative examples of typical heating equipment for each modality are given in the following subsections.

FIGURE 31.5. Photograph of three different-size microwave waveguide applicators used with the BSD 500 Hyperthermia system from BSD Medical (Salt Lake City, UT).

Electromagnetic Heating

When a radiofrequency electric field (E field) is applied to tissue, heating occurs from resistive losses as a result of electric current in a resistive media (tissue). At higher microwave frequencies, heat is generated from mechanical interactions between adjacent polar water molecules aligning to the alternating EM field. In either case, energy deposition is proportional to the electrical conductivity and square of the time-averaged E field. Electrical conductivity varies 50-fold depending on tissue type and frequency, with higher conductivity for high-water-content tissues like muscle and internal organs and much lower conductivity for fat and bone. The electrical properties of most tissues have been characterized over a large range of frequencies and published previously.104 Power deposition has better penetration with lower-frequency, longer-wavelength fields, but the longer the wavelength, the broader is the focus of heating. To obtain deep penetration in the body, multiple-antenna arrays are required to diffuse surface heating, and in combination with the longer wavelengths this produces regional energy deposition that involves substantial volumes of tissue.

EM heating devices can be separated into two categories: superficial HT applicators, with effective penetration into tissue in the range of 1 to 4 cm; and deep HT devices, which have effective penetration >4 cm. Superficial HT devices include waveguides, modified horns,105 capacitive and inductively coupled sheet antennas,106,107 and microstrip108,109 or patch antennas110 that typically operate at 433, 915, or 2,450 MHz. In recent years, multiple-antenna planar and conformal array applicators have become more common to increase the size of tumor that can be heated, as well as to provide lateral adjustment of power deposition to accommodate heterogeneous tissue. These devices provide lateral adjustment of the power deposition pattern to equilibrate hot and cold regions across a tumor. Superficial microwave applicators are usually coupled into tissue through a deionized water bolus to accommodate surface irregularity. In addition, the bolus is usually temperature controlled to help maintain skin temperature below 44°C. Although current developmental multiantenna array applicators should be available commercially in the near future, the majority of superficial clinical HT is performed with BSD Medical (Salt Lake City, UT) waveguide applicators in the United States and Lucite cone applicators105 or contact flexible microwave applicators111 in Europe. Figure 31.5 shows typical waveguide applicators used for heating up to 20 × 15 cm superficial chest-wall disease.

In order to heat at depths >4 cm, one must use lower frequencies in the radiofrequency (RF) band from 50 kHz to 150 MHz. There are three basic techniques for EM power deposition deep in tissue: magnetic induction heating, capacitively coupled RF current heating, and RF phased-array heating. Magnetic fields penetrate to the body axis but induce local eddy current loops that are governed by paths of least resistance and cause power deposition peaks and nulls that cannot be controlled externally. Although regional heating with magnetic induction failed to show sufficient control clinically,112 there is interest in using magnetic fields to couple energy into implanted ferromagnetic seeds113 and nanoparticles.114

The capacitive coupling technique uses RF fields from 5 to 30 MHz to drive currents between two or more saline pad electrodes. Heat is concentrated under the electrodes in tissues with high resistance (e.g., fat). The electrodes are generally aggressively cooled to prevent hot spots on the skin surface and superficial fat.115 Although there is lack of real-time adjustment of heat distribution during treatment, energy can be concentrated on one side using a smaller electrode. The technique has been used effectively in the clinic for superficial and moderate depth tumors, predominantly in Asian patients with thin fat layers that can be cooled sufficiently with surface cooling.116–117,118,119 Another possible approach is to drive RF current between an interstitial needle and a large-surface-area return electrode to focus heating at depth around the implanted electrode. Similarly, this can be done with an implanted balloon electrode for intracavitary applications (e.g., esophagus).120

The third option for noninvasive deep heating is the RF phased-array technique, which uses a body-concentric array of dipole antennas121,122 or large waveguides.123 Driving multiple antennas with equal phase produces a heat focus centrally in a concentric array, providing much deeper penetration than is possible operating the antennas noncoherently. By applying a phase delay to some of the antennas, one can steer the central focus laterally. Systems in the 1990s included four separate phase- and amplitude-controlled antennas in a single concentric array around the body. Since then, both dipole and waveguide array systems have been expanded to include two or three rings of antennas to provide axial as well as lateral adjustment of heating at depth.123,124–125 In general, RF phased arrays have more flexibility in adjusting the SAR pattern than magnetic induction and capacitive heating techniques. The capacitive approach, such as Yamamoto Thermotron RF-8 (Yamamoto Vinita, Osaka, Japan), and RF phased-array applicators like the BSD Medical Sigma Ellipse and Sigma Eye are the most frequently used deep heat systems. Figure 31.6 shows a patient setup in the Sigma Ellipse applicator for treatment of non–muscle-invasive bladder cancer.

FIGURE 31.6. Photograph of non–muscle-invasive bladder cancer patient during deep regional hyperthermia treatment in BSD 2000 Sigma Ellipse applicator (BSD Medical, Salt Lake City, UT).