HYPEROSMOLAR SYNDROMES

Hyperosmolar or hypernatremic syndromes may be defined as plasma osmolality levels and sodium concentrations of >300 mOsm/kg and >145 mEq/L (145 mmol/L), respectively. Although rare, they constitute a major management challenge.

ETIOLOGY

Transient hyperosmolality may occur after the ingestion of large amounts of salt,34 but most hypernatremic states occur after inadequate water intake. This can occur in any healthy individual in whom the combination of excess fluid loss—from skin, gastrointestinal tract, lungs, or kidneys—and inadequate access to water is found. This occurs most commonly in acute illness in which water intake is compromised by vomiting or impaired consciousness and most vividly in patients with diabetes insipidus, before treatment, or when access to water is denied. In other cases, however, hypernatremia reflects a primary disorder of thirst deficiency (hypodipsia).

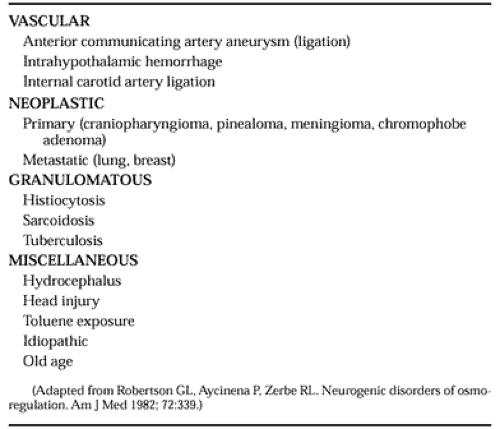

A number of conditions are associated with hypodipsia (Table 26-2). One of the more common causes of hypodipsic hypernatremia that the authors have seen is ligation of the anterior communicating artery, after subarachnoid hemorrhage from a berry aneurysm. Other centers have reported that neoplasms account for 50% of such cases.35 Craniopharyngiomas are particularly associated with hypodipsic diabetes insipidus, sometimes in conjunction with other hypothalamus-related disorders, such as polyphagia, weight gain, and abnormal thermoregulation. Survivors of diabetic hyperosmolar coma have been shown to have impaired osmoregulated thirst,35 which suggests that hypodipsia contributes to the development of the hypernatremia, which is characteristic of the condition. In almost every case of hypodipsia, associated abnormalities of vasopressin secretion are seen, a finding that reflects the close anatomic proximity of the osmoreceptors for vasopressin secretion and thirst.

CLINICAL FEATURES

In young children and the elderly, hypernatremia may be associated with significant degrees of dehydration.36 Infants are at particular risk, and the mortality is high. In this clinical situation, signs are seen of extracellular fluid loss, decreased skin turgor and elasticity, dry and shrunken tongue, tachycardia, and orthostatic hypotension. Affected infants have depressed fontanelles and tachypnea, and their respirations are deep and rapid. Fever is often present, and the temperature may be as high as 40.5°C (105°F). Adults with mild hypernatremia may have no symptoms, but as plasma sodium levels rise above 160 mEq/L, neurologic signs become apparent.36,37 Early symptoms include lethargy, nausea, and tremor, which progress to irritability, drowsiness, and confusion. Later features of muscular rigidity, opisthotonus, seizures, and coma reflect generalized cerebral and neuromuscular dysfunction. The most severe neurologic disturbances are seen at both ends of the age spectrum. The severity of such disturbances is also related to the rate at which hypernatremia develops, as well as to the absolute degree of hyperosmolality. Intracerebral vascular lesions are often the cause of death.

In contrast to patients with the life-threatening clinical features of hypernatremic dehydration, patients with long-standing, moderate hypernatremia (plasma sodium concentrations of 145 to 160 mEq/L) may have few manifestations of the disorder other than lack of thirst. Hypodipsia is the crucial symptom, but it is often overlooked in the clinical setting because patients fail to complain of lack of thirst. However, careful evaluation of these patients reveals that some have no desire to drink any fluid under any circumstances, which suggests a total loss of the thirst osmoreceptor function. Others have only minimal thirst with marked hypertonicity, whereas a third group eventually experiences a normal thirst sensation, but only at high plasma osmolality levels.

The key to recognizing subtle differences in thirst appreciation rests with a satisfactory measure of thirst. Visual analog scales for measuring thirst during dynamic tests of osmoregulation38,39 have been shown to produce highly reproducible results.40 When these scales are used in evaluating healthy persons, a linear increase is noted in the degree of thirst and fluid intake with increase in plasma osmolality, and an osmolar threshold for thirst is seen that is a few milliosmoles per kilogram higher than the osmolar threshold for vasopressin secretion.39 The application of these techniques to patients with chronic hypernatremia has disclosed numerous disorders of osmoregulation.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree