Chapter 17

How BRCA Affects Men

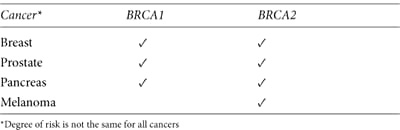

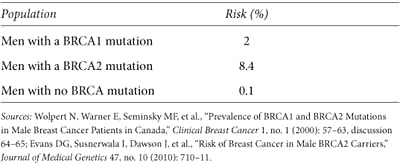

LIKE WOMEN, MEN CAN INHERIT BRCA MUTATIONS from either parent. And when they do, like women, they face an increased lifetime risk of certain cancers (see table 16). When men have BRCA mutations, however, their risk for breast cancer is lower than women who have the same mutation. Men should consult with a genetic counselor when they:

• have an inherited BRCA mutation in the family.

• have been diagnosed with breast cancer, young-onset prostate cancer, or pancreatic cancer.

• have prostate cancer and a family history of breast cancer or ovarian cancer.

• have male relatives who have had breast cancer.

• have female relatives who have had breast cancer, particularly before age 50, or ovarian cancer at any age.

• are of Jewish ancestry and their family history includes breast, ovarian, pancreatic, or prostate cancer.

Table 16. BRCA mutations increase a man’s risk for cancer

Men Get Breast Cancer Too

We hear a lot about breast cancer in women, but few men are aware that they’re also at risk (see table 17). Male breast cancer doesn’t often happen, even among men with mutations. Malignancies in the small amount of breast tissue behind the male nipples account for fewer than two thousand total cases in the United States each year—that’s about one man diagnosed for every one hundred women with the disease. Among men who develop breast cancer, about 8 percent have a BRCA mutation.1 Any man diagnosed should consider risk assessment with a genetics expert.

Research specific to breast cancer in men with BRCA mutations is sparse. The following factors are known to increase the likelihood of breast cancer in men of average risk and may also affect men with mutations.

Table 17. Estimated male lifetime breast cancer risk to age 80

• growing older

• having family members of either gender who have breast cancer

• being alcoholic or obese, or having chronic liver disorders—conditions that raise estrogen levels

• having Klinefelter syndrome, a rare male genetic disorder that creates high estrogen levels. Men with Klinefelter are 20 to 50 times more likely to develop breast cancer than other men2

• having gynecomastia, a benign condition characterized by enlargement of male breast tissue, obesity, or other factors, may increase the risk for breast cancer

Screening and Treatment

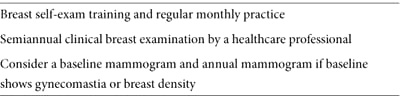

Men approach their overall health much differently than women, often avoiding routine health screenings or regularly seeing physicians. Most men don’t routinely check their breasts (see NCCN screening guidelines in table 18). If they do find a suspicious area, they’re more likely than a woman in the same situation to ignore it. Any of the following symptoms may indicate a benign breast condition or breast cancer and should be reviewed right away by a physician. Early treatment can be lifesaving.

Table 18. NCCN breast cancer surveillance guidelines for men with BRCA mutations

• a nipple that itches, is sore, is scaly, has a rash or discharge, or appears different

• a lump or thickening in the breast or chest (Breast abnormalities may be more noticeable in a man’s small breast.)

• dimpling or puckering of the breast skin

Most breast malignancies found in men are invasive ductal carcinoma. Less frequently, invasive lobular carcinoma, inflammatory breast cancer, or DCIS develops. Men with breast cancer have greater risk for a malignancy in the opposite breast, particularly when diagnosed before age 50.

Tumors with the same pathology are generally treated alike, whether they occur in men or women, and survival rates are similar when treatment begins at the same stage. By the time men see a doctor, however, their tumors are often more advanced, with a poorer outcome. Clinical breast exam, mammography, ultrasound, and biopsy may all be used to detect and stage a malignancy. The first line of treatment is a total or modified radical mastectomy with sentinel node biopsy or axillary lymph node dissection to determine whether the cancer has spread. Lumpectomy isn’t usually an option because, compared to a woman, a man’s tumor involves a larger proportion of his breast. Depending on stage and tumor characteristics, surgery may be followed by chemotherapy (it may also be used before surgery to shrink the tumor), and sometimes radiation. Tamoxifen is usually prescribed for five years if a tumor is ER+, as most male breast cancers are, with the potential for similar side effects experienced by women: headache, nausea, leg cramps, bladder control issues, and rashes. Megace, a drug that blocks the effect of the male hormone androgen, may be used instead. Some oncologists prefer aromatase inhibitors to block estrogen; although they work against female breast cancers, they haven’t been well studied in men. They tend to thin the bones (a bisphosphonate may be prescribed to offset this side effect) and can cause stiff joints. If initial hormonal therapy fails, medications called gonadotropin inhibitors may be used to lower hormone levels. Breast cancers that overexpress HER2/neu may be treated with trastuzumab (Herceptin) and chemotherapy.

MY STORY: Thriving after BRCA and Breast Cancer

I’m an 81-year-old father of four and grandfather of six. None of these is an unusual accomplishment except that I’m also a seven-year survivor of breast cancer. I found the lump while showering. A mastectomy followed, as did a bout with bladder cancer. And prostate cancer. And skin cancer. After my breast cancer diagnosis and learning I was BRCA2 positive, my four children were tested. True to the 50/50 chance of inheriting my mutation, two were positive, two were negative. I’m still here, surviving and thriving—it’s entirely possible.

Most people don’t know that men can get breast cancer. My advice to other men is to get in the shower and run your hands all over yourself. And if any family members have had breast cancer, go get the BRCA test. It’s a simple blood test that may save your life or the life of someone you love.

—GUY

High Risk for Prostate Cancer

Prostate cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer in North American men—and in men with BRCA mutations—and the second leading cause of male cancer deaths. In most cases in the general population, it’s a particularly slow-growing disease, and most men die with it, not because of it. That’s not always the case with men who have a BRCA2 mutation—their lifetime risk is particularly high: about 1 in 3; the average man’s risk is 1 in 6. BRCA2-related prostate cancer may develop before age 50, is more aggressive, and has a poorer prognosis.

Early prostate cancer usually shows no symptoms. Most doctors routinely recommended an annual prostate-specific antigen (PSA) blood test to screen men over age 50 until a 2009 study showed that, based on PSA results, more than 1 million men in the United States were over-treated for tumors that grew too slowly to do harm.3 This is significant, because up to one-third suffer from incontinence, impotence, and other life-affecting side effects—not from the cancer, but from treatment. This study prompted the American Cancer Society to modify its recommendations. Current guidelines (which are complex) for the general population of men advise against PSA testing until they talk with their doctors and have enough information to make an informed decision about whether to have the test. The discussion is recommended at:

• age 50 for men of average risk who are expected to live at least ten more years.

• age 45 for African American men and those who have a first-degree relative diagnosed with prostate cancer before age 65.

• age 40 for men with several first-degree relatives who had prostate cancer before age 65.

These guidelines are inadequate for BRCA2 mutation carriers, who may be more likely to die from their prostate cancer since it has a higher likelihood of being aggressive. The NCCN recommends a PSA test and baseline digital rectal exam for all men with BRCA mutations, starting at age 40. The international IMPACT study is comparing the benefit of prostate screening in men ages 40 to 69 who have BRCA mutations with those who don’t. Study results (expected in 2020) will clarify the benefits of prostate cancer screening in high-risk men. Initial study findings suggest that PSA screening is effective in BRCA mutation carriers: an elevated PSA more likely signified prostate cancer in their biopsy, they were less likely to undergo a biopsy for an unfounded reason, and their cancers were generally more aggressive, requiring treatment.4 Enroll or follow the study online (www.impact-study.co.uk).

Otherwise healthy men who are diagnosed before age 60 with cancer confined to the prostate are usually treated with prostatectomy (removal of the prostate gland) or radiation (either external radiation over several weeks or via one-time brachytherapy, which plants radioactive seeds in the prostate). Erectile dysfunction and urinary incontinence may result from either treatment. When surgery isn’t an option or when an advanced tumor is contained in the prostate, cryosurgery may be used to freeze the gland to kill the cancer. It’s unclear whether this procedure works as well as surgery or radiation in the long term, and side effects depend on the surgeon’s skill.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree