HORMONAL CONTRACEPTION

Part of “CHAPTER 104 – FEMALE CONTRACEPTION“

COMBINATION ORAL CONTRACEPTIVES

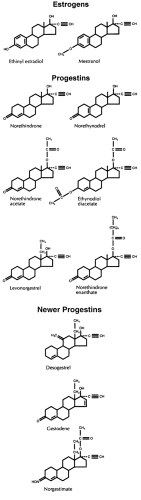

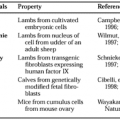

Combined oral contraceptive pills (COCs) contain various doses of synthetic estrogen (ethinyl estradiol or mestranol) and a synthetic progestin. All the synthetic estrogens and progestins used in oral contraceptives have an ethinyl group on the 17 position that enhances their oral activity by slowing hydroxylation and conjugation in the liver3,4 (Fig. 104-1).

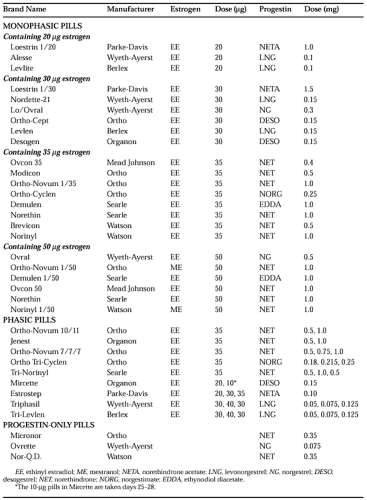

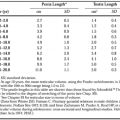

Table 104-3 lists all oral contraceptives (except some generic forms) currently marketed in the United States, ranked according to the dose of estrogen. Low-dose COCs contain <50 μg of estrogen and are the primary choice for oral contraception. COCs containing ≥50 μg of estrogen should no longer be routinely used for contraception. Variable-dose products are either biphasic or triphasic, depending on the number of dose regimens in a cycle, and are all low dose.

The introduction of the new progestins—desogestrel, norgestimate, dienogest, and gestodene (the latter two are not sold in the United States)—has created a new classification system for COCs. Pills containing ≥50 μg of estrogen are called “first-generation” COCs; COCs containing <50 μg of estrogen and any of the older progestins are termed “second generation”; and low-dose COCs containing the new progestins—desogestrel, dienogest, gestodene, and norgestimate—are called “third-generation” COCs. Classifying low-dose COCs by the androgenic effects of their progestins is clinically more useful than the “generational” approach5; the newest progestins (desogestrel, dienogest, gestodene, and norgestimate) are less androgenic than other progestins. (For an explanation, see later section on the noncontraceptive benefits of COCs.)

MECHANISM OF ACTION

The progestin component is primarily responsible for the contraceptive effect of COCs. Synthetic progestins inhibit the mid-cycle luteinizing hormone (LH) surge, thereby suppressing ovulation. Progestins also cause changes in cervical mucus that retard sperm penetration and inhibit conception. Progestins alter the motility of the uterus and the fallopian tubes, hindering conception by altering the transport of sperm and ova. Progestins also affect glycogen production by the endometrium and ovarian steroidogenesis; whether this mechanism of action contributes to the contraceptive effect of progestins is unknown.

The estrogen component of COCs inhibits follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), preventing the selection of a dominant follicle. It also potentiates the effects of the progestin, probably on an intracellular level, allowing use of a lower dose of progestin. Finally, the estrogen component of COCs provides stability to the endometrial lining and prevents the irregular bleeding that progestins provoke when used alone.

USE OF COMBINED ORAL CONTRACEPTIVES

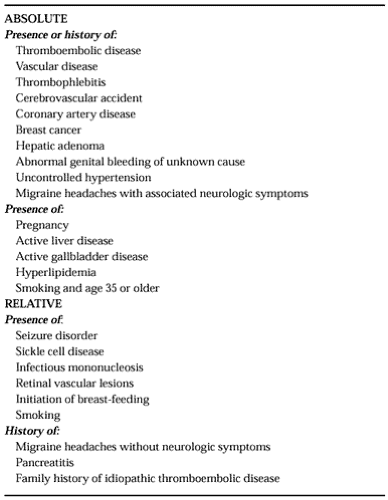

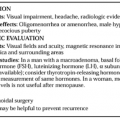

Table 104-4 lists for COCs the absolute and relative contraindications that have evolved over 30 years of experience with the pill. These contraindications are related primarily to the estrogen component of COCs. Much of the epidemiologic and physiologic evidence supporting these contraindications was obtained from the evaluation of COCs containing ≥50 μg of estrogen. Consequently, with the use of smaller doses of estrogen (and of progestin), several contraindications considered absolute for high-dose COCs are only relative contraindications with the lower-dose products.

The clinician should prescribe the lowest dose of estrogen and progestin consistent with high efficacy and few side effects. Only low-dose COCs (<50 μg of estrogen) should be prescribed routinely for contraception. When starting a woman on low-dose COCs, the clinician should consider whether she would benefit from low androgenic activity in the progestin component. Pills containing desogestrel or norgestimate are a good first choice for a woman who may be hyperandrogenic.5 Other women may benefit from a COC with the lowest possible dose of estrogen. A woman who has successfully used a particular low-dose pill in the past should resume its use unless her health has changed.

Products containing 50 μg of estrogen are generally reserved for women who are taking a medication known to increase the metabolism, and, therefore, to decrease the efficacy of estrogen (i.e., barbiturates, phenytoin, carbamazepine, rifampin). The 50-μg pills are also used for emergency contraception (see later) and for the acute treatment of menorrhagia. Women taking pills containing 50 μg of estrogen for routine contraception should be switched to a low-dose pill; pills containing >50 μg of estrogen cause more side effects and are no more effective than lower dose pills. Moreover, most pharmaceutical companies have stopped selling high-dose pills for routine contraception.

PILL TAKING AND MISSED PILLS

Combination oral contraceptives are taken for 21 days of the cycle, starting on day 1 of the menses or the first Sunday after the onset of menses. The 21 days of hormonally active pills are followed by 1 week without medication during which withdrawal bleeding occurs. Many preparations contain 21 active pills and 7 placebos for an easy-to-remember 28-day cycle.

Some preparations (Loestrin Fe 1/20 and 1.5/30) contain 75 mg of iron per day for 7 days in place of the placebos. One preparation (Mircette) replaces the last 5 placebo days with 10 μg of estrogen per day.

Some preparations (Loestrin Fe 1/20 and 1.5/30) contain 75 mg of iron per day for 7 days in place of the placebos. One preparation (Mircette) replaces the last 5 placebo days with 10 μg of estrogen per day.

The pills should be started no later than day 5 of the menstrual cycle, because pills missed early in the cycle increase the risk of breakthrough ovulation and contraceptive failure. If one pill is omitted at any time during the cycle, it should be taken as soon as remembered. Some vaginal bleeding may occur, but no backup method is necessary. If two pills are missed within the first two weeks of the cycle, then once the omission is remembered, two pills per day should be taken for 2 days. An additional method of contraception, such as a barrier method, should be used for 7 days and the rest of the pill cycle should be completed. If two pills are missed within the third week of the cycle by a woman who started her COCs on day 1 of her menses, she should start a new pack as soon as possible and use backup contraception for 7 days. If 2 pills are missed in the third week of the cycle by a woman who was a Sunday starter, she should continue taking the current pills until the next Sunday and then start a new package; she should also use backup contraception for 7 days. If three or more pills are missed at any time, a backup method should be started immediately and continued for 7 days. If the woman prefers not to have menses on weekends, she should continue the current pack until the next Sunday and then start the new pack. If the timing of menses is not a concern, or coordinating a Sunday start is too confusing, she should simply start a new package of pills immediately.

After women answer questions about possible contraindications to COCs and are given a baseline blood pressure check and screening physical examination, they may be prescribed pills. Within 3 months of beginning pill use, women should have their blood pressure and weight measured. Patients using oral contraceptives should be seen by a clinician once or twice a year, and at this visit a routine physical examination including abdominal, breast, and pelvic examinations should be performed.

No reason exists for patients to take a break from COC use, except when pregnancy is desired or a serious complication develops. The ability to conceive after discontinuing oral contraceptive use is not impaired.6 In nonsmoking women, COC use can be continued until menopause.

MINOR SIDE EFFECTS

The incidence of minor side effects varies significantly from one report to another. Nausea or vomiting is related to the dose of estrogen, is much reduced when products containing <50 μg of estrogen are used, and usually abates after 3 months of use. Management includes reassuring the patient, instructing the patient to take the pill at bedtime and to eat just before swallowing the pill, or, finally, changing to the lowest estrogen dose COC available (20 μg).

The most common pill-related side effect is breakthrough bleeding; it usually results from the inability of the hormones to maintain the endometrium for the full 21-day course of therapy and improves after 2 or 3 months. Bleeding can also occur because of failure to take the pill at the same time each day or omission of the pill for 1 or 2 days. Switching to another low-dose product containing a different progestin or from a phased to a steady dose COC often improves breakthrough bleeding. Should these measures not prove effective, possible pathologic causes of the bleeding should be investigated.

Some women using COCs experience amenorrhea. Once pregnancy has been ruled out, the patient can be reassured that the occurrence of amenorrhea while on COCs is not harmful. If the patient desires monthly withdrawal bleeding, changing to a low-dose pill with a higher estrogen dose or one containing a less androgenic progestin is recommended.

Weight gain is an often-cited side effect of pill use and is often a reason for discontinuation. Despite claims that COCs cause weight gain, studies have been unable to document a significant increase in mean weight in COC users.7 Some perceived weight gain may represent bloating or fluid retention rather than an anabolic effect. Also, women tend to gain weight with increasing age, and age-related weight gain may be blamed on COC use. Nonetheless, some women do experience weight gain attributable to COCs. If the weight gain cannot be controlled with diet and exercise and is unacceptable, an alternative form of contraception may be necessary.

Mood changes, including depression, lethargy, loss of libido, irritability, sleep disturbances, and changes in appetite, occur in ˜5% of oral contraceptive users. The severity of these symptoms, and the acceptability of contraceptive alternatives, should help women and their clinicians decide whether discontinuation is necessary.

SERIOUS SIDE EFFECTS

Adverse effects reported with the use of COCs include thromboembolic disorders, cerebrovascular disorders, myocardial infarction, optic neuritis, hepatic adenoma, cervical dysplasia and carcinoma, exacerbation of biliary colic and cholecystitis, decreased carbohydrate tolerance, hypertension, migraine or vascular headache, psychic depression, and chloasma. These potentially serious side effects are estrogen related and are rare. Complications of steroidal contraception are discussed in further detail in Chapter 105.

Many of these adverse effects were initially observed among women taking COCs containing ≥50 μg of estrogen and markedly higher doses of progestins than are used today. Studies of COCs containing ≥50 μg of estrogen showed an increased risk of venous thromboembolism, stroke, myocardial infarction, and hypertension.8,9

Among healthy nonsmoking women, studies of low-dose COCs have shown an increased risk of venous thromboembolic disease, but no significantly increased risk of stroke, myocardial infarction, or hypertension.8,9,10,11 and 12 In the long term, current and past COC users do not have an increased risk of mortality compared with those who never used COCs.13

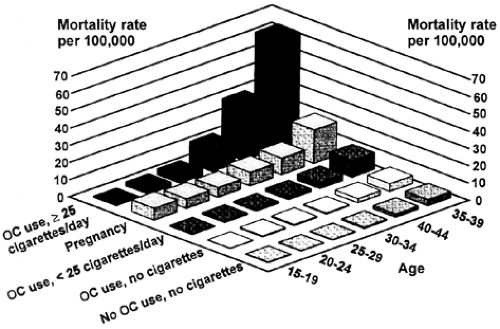

Smokers, women with genetic risk factors (e.g., the factor V Leiden mutation), and those with medical problems that predispose them to vasculopathies are at higher risk than other subgroups.14,15 Smoking appears to have a synergistic effect with COCs in increasing the risk of myocardial infarction, stroke, and venous thromboembolic disease.16 This synergism has less impact on women aged younger than 35 years, whose overall risk for cardiovascular disease is extremely low. However, for women aged 35 years or older, the risk of dying from cardiovascular disease is 3.0 per 100,000 nonsmoking COC users; 10.0 per 100,000 smokers not using COCs; and 29.4 per 100,000 smokers using COCs16 (Fig. 104-2). This level of risk is unacceptable; therefore, COC use is contraindicated in smokers older than 35 years of age. Among other high-risk populations, the use of COCs involves a fine balancing of benefit versus risk.17

NONCONTRACEPTIVE BENEFITS OF ORAL CONTRACEPTIVE USE

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree