Fig. 3.1

Case described by Krause in 1862. Elongated left arm with visible pulsating “angiomata,” present since the age of 7. At the age of 45, the arm was amputated after appearance of ulcers on the fingers (Reproduced with permission from Krause [23])

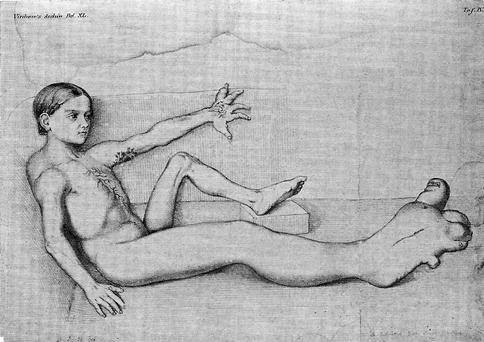

Fig. 3.2

Case described by Friedberg in 1867. A girl aged 10 with a hypertrophy of the right leg with a limb length discrepancy of 18 cm. This patient had also lymphangiomas on the left arm and hand with repeated episodes of phlebitis and lymphangitis, treated by wet packs and digitalis. She died of tuberculosis few years later (Reproduced with permission from Friedberg [24])

Between 1907 and 1918, F. Parkes-Weber published different cases of limb hypertrophy and described signs of AV fistulas as “…a definite thrill or pulsation… is transmitted to the veins.” He put together different vascular dysplasias, ranging from lymphangioma, nevus, and cirsoid aneurysm to diffuse AV fistulas, and labeled all these cases as “hemangiectatic hypertrophy of limbs” [27–29].

The efforts of all these authors were limited by the lack of diagnostic technology and were therefore only based on clinical data.

The year 1923 marked a new step in diagnostics after the introduction of arteriography by Sicard and Forestier [30] using Lipiodol in France and by Berberich and Hirsch in Germany, injecting strontium bromide [31]. Arteriography made it possible to better study the hemodynamic of vascular malformations.

Dysplasias of the deep veins of the lower limbs were studied by Servelle with phlebographies. In 1962 he described stenosis of the popliteal vein due to compression of fibrous bands [32], but this data was not confirmed by others. Pathogenesis of limb overgrowth was considered to be due to the venous stasis. Soltesz demonstrated experimentally with angiography that AV shunts open by performing ligature of popliteal veins in young animals; he concluded that limb hypertrophy is always due to AV fistulas [33].

A significant contribution toward comprehension of the different types of CVM was the paper of de Takats [34]; he made a clear distinction between AV malformations and other vascular defects, such as pure venous malformations and venous “angioma.” Differentiation between hemangioma and vascular malformation was difficult. Even though Ewing in 1940 defined the hemangioma as a vascular tumor, different from a vascular malformation [35], only the publication of Mulliken and Young in 1988 was able to definitively clarify the difference [36].

Reports of cases with CVM of the limbs and limb shortening instead of hypertrophy were described later. In 1948 Servelle and Trinquecoste described two cases of venous hamartoma of the limbs with phleboliths and bone hypotrophy [37]. Martorell described a similar case in 1949 with “angiocavernomas” and severe bone destruction; he called this syndrome “angiomatosis braquial osteolitica” [38]. In 1957 Olivier distinguished two different types of “varicose angiomatosis,” one superficial and one with deep-sited “angiomas” [39]. The opinion that even these venous-appearing malformations had AV communications was expressed by Pratt (1949) and Piulachs and Vidal Barraquer (1953) [40, 41].

Lymphatic dysplasia was described clearly in the nineteenth century. Cystic hygroma was first described by Wernher in 1843 [42]. Wegener (1877) divided lymphatic dysplasias or lymphangiomas into simplex, cavernosum, and cysticum types, a classification which is accepted even today [43]. Extensive studies on diagnosis and treatment of lymphatic malformations were carried out by Kinmonth [44] and Servelle [45]. The rare condition of chylus reflux was first reported clearly by Servelle and Deysson in 1949 [46]. Reports of combination of peripheral vascular malformations and lymphatic dysplasia were still included in some historical papers, like those of Klippel and Trenaunay and Parkes-Weber, but clear recognition of the lymphatic component was not achieved. Better data appeared only recently due to Pierer [47], Lindemayr et al. [48], and Partsch (1968) and also in the cited work of Kinmonth, among others.

In 1965 Malan published two papers in which he extensively analyzed all types of CVM, trying to clear problems of classification, diagnostics, and treatment [49, 50].

The first monograph, Abnormal Arteriovenous Communications, was published by Holman in 1968 [51] and was followed by the books of Belov in 1971 [52] and those of Giampalmo in 1972 [53]; the latter two had little diffusion because of their languages (Bulgarian and Italian). In 1974 Malan published his monograph in English with a report of 451 cases [54], followed by those of Schobinger [55]. Other remarkable works were due to Dean and O’Neal (1983) [17], Belov et al. [56], and Mulliken and Young [36].

Surgical treatment of CVM had been attempted for many years. Sometimes results were disappointing, as reported by Szilagyi et al. in 1976 [57]; however, other authors, like Vollmar [58], Malan [59], and Belov [60], had better results. Belov was the first person to put surgery into a systematic level.

Endovascular treatment was attempted first by Brooks in 1930: the author embolized a traumatic carotido-cavernous fistula with muscle fragments attached to a silver clip [61]. In 1960 Lussenhop and Spence embolized an intracranial AV malformation with spheres of methyl methacrylate through a surgically exposed common carotid artery [62]. Development of catheter technology and embolizing materials after 1970 increased the interest in these techniques. Zanetti and Sherman reported embolization with isobutyl 2-cyanoacrylate [63] and Carey and Grace with Gelfoam particles [64], while Gianturco created the coil in 1975 [65]. Yakes proposed the occlusion of CVM by alcohol injection through a direct puncture [66].

Recent progress was the publication of an international consensus, led by BB Lee with a selected group of international experts about venous malformations in 2009 [67] and about arteriovenous defects in 2013 [68].

In 1976, Anthony Young (London) and John Mulliken (Boston) organized a small meeting with other colleagues interested in these problems, in order to exchange experiences and discuss difficult cases. Meetings were held every 2 years as interest in them increased. During the congress held in 1990 in Amsterdam, organized by Jan Kromhout, a group of experts agreed to find a scientific society to convene all the physicians interested in vascular malformations and hemangiomas, in order to obtain international acceptance. During the meeting held in Denver in 1992, organized by Wayne Yakes, the new society was founded. The first assembly agreed on the name International Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies (ISSVA). The first president was Robert Schobinger (Switzerland). Today, ISSVA meets every 2 years. It brings together a multidisciplinary group of experts from all over the world dedicated to approaching these difficult topics. Interest in these diseases is growing and progress is on its way.

References

1.

Guido G, cited by Vichow R (1876) Pathologie des Tumeurs. Germer-Balliére, Paris

2.

Whitterige G (1966) The anatomical lectures of William Harvey. E & S Livingstone, Edimburg and London