HIRSUTISM

DEFINITION

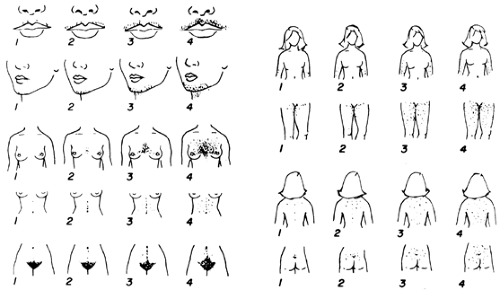

Hirsutism is the development of excessive androgen-stimulated terminal hair in a female in areas where terminal hair is not normally found. Various descriptive and quantitative scales have been used to document the process, but none is ideal. The modified Ferriman-Gallwey system is the most reliable (Fig. 101-12). However, this scale is subjective and requires grading of hair from specific body sites that may not include some important areas.

Hirsutism is characterized by increased numbers of terminal hairs in certain regions of the body. The chin, upper lip, and sideburn area often are involved, as are the neck, chest, shoulders, upper back, upper abdomen, and medial portions of the thighs. A diffuse increase in hair on the arms and legs may be noted. Hair on the knuckles and ears of women is unusual and may indicate the presence of virilization. Hirsutism can be a mild cosmetic problem that requires only reassurance and cosmetic therapy, or it can have considerable psychological impact necessitating other treatments. Hirsutism can also be an indication of an underlying illness.

DIFFERENTIATION FROM VIRILIZATION

Although hirsutism often affects virilized individuals, the terms should not be used interchangeably. Virilization includes defeminizing signs (e.g., loss of female body contour, flattening of the breasts), increased libido, and frank masculinization (e.g., muscle mass increase, temporal balding, deepening of the

voice, laryngeal hypertrophy, clitoromegaly). This extreme form of androgen excess is the product of time and hyperandrogenemia. Women rarely exhibit virilization unless serum testosterone levels are above 200 ng/dL. Interestingly, serum specific antigen (PSA) is statistically increased in hirsutism, and appears to be a marker of androgenation.58a

voice, laryngeal hypertrophy, clitoromegaly). This extreme form of androgen excess is the product of time and hyperandrogenemia. Women rarely exhibit virilization unless serum testosterone levels are above 200 ng/dL. Interestingly, serum specific antigen (PSA) is statistically increased in hirsutism, and appears to be a marker of androgenation.58a

CRYPTIC HYPERANDROGENISM

Cryptic hyperandrogenemia, characterized by absence of hirsutism or acne, can be encountered in anovulatory women and in women with the cryptic form of congenital adrenal hyperplasia (see Chap. 77).59,60 The cause of this paradox is important to an understanding of the manifestations of androgen excess. In the expression of hyperandrogenism, the “signal” (in the form of secreted androgens) and the level of sensitivity of the PSU in the affected areas are important. This sensitivity, which includes 5α-RA, also involves genetic and other factors that can modulate the growth or regression of the PSU. In the case of cryptic hyperandrogenism, an elevated circulating androgen level (i.e., the signal) is not sufficient to cause hirsutism.

HIRSUTISM AND HYPERANDROGENISM

Three major concepts link androgen with hirsutism:

Androgen is necessary to recruit terminal hair development.

Androgen prolongs the time spent in the anagen phase of hair growth.

5α-RA within the PSU modulates the androgenic signal.

On the scalp, a generally androgen-unresponsive area, anagen lasts 3 years; on the face, it lasts ˜4 months if not abnormally stimulated by androgen.Telogen phases average 3 months for scalp and facial hair. The prolonged anagen of scalp hair explains the greater length of hair in this area. Anagen on the thighs of men averages 54 days but is only 22 days in women. Moreover, axillary hair growth is 10% faster in men than in women.61 With stimulation by androgen in androgen-responsive areas, the length of anagen is longer, terminal rather than vellus hairs appear, and the hair is thicker.

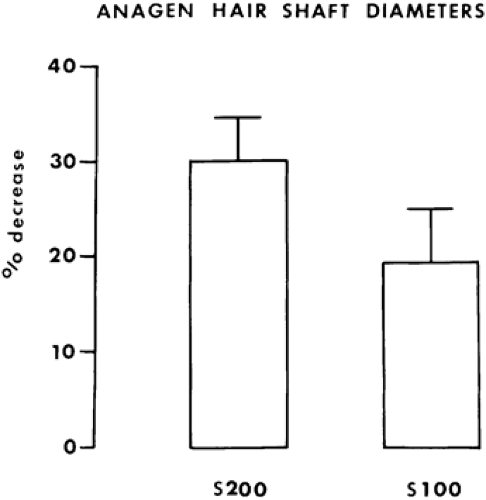

The latter findings, which explain hair density in hirsutism, have been inferred from antiandrogen therapy with cyproterone acetate and spironolactone. A major effect of antiandrogen therapy is to convert terminal hairs to vellus hairs. Figure 101-13 shows the dose-response change in thickness of anagen hair with spironolactone treatment.

Differences are seen in the expression of 5α-RA in men and in women. Male genital skin expresses both isoenzymes of 5α-reductase, but with a marked preponderance of isoenzyme type 2.62 On the other hand, female genital skin expresses almost exclusively 5α-reductase type 1, and levels of 5α-reductase type 2 are very low.62 Hirsute hyperandrogenic women exhibit a pattern of 5α-reductase isoenzymes that is similar to that of normal women, but in hirsutism a much higher concentration of 5α-reductase type 1 is found.62,63 Therefore, both in acne and in hirsutism, an increase of the type 1 isoenzyme is found that probably occurs as a consequence of androgen excess.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF ANDROGEN EXCESS

Patients with hirsutism must be evaluated for hyperandrogenemia. If hyperandrogenism is found, a differential diagnosis of androgen excess should be considered.

DRUG EFFECTS AND SYSTEMIC CONDITIONS

Careful history-taking and a careful physical examination can eliminate the possibility of drug-induced androgen excess, the

androgen insensitivity of genetic males, and several systemic conditions. Many preparations may contain androgen. Drugs such as diphenylhydantoin, some oral contraceptives, danazol, minoxidil, and diazoxide are known to cause hirsutism. Corticosteroid therapy can cause hirsutism; female athletes or women with conditions such as aplastic anemia who are taking anabolic agents may have hirsutism (see Chap. 119).

androgen insensitivity of genetic males, and several systemic conditions. Many preparations may contain androgen. Drugs such as diphenylhydantoin, some oral contraceptives, danazol, minoxidil, and diazoxide are known to cause hirsutism. Corticosteroid therapy can cause hirsutism; female athletes or women with conditions such as aplastic anemia who are taking anabolic agents may have hirsutism (see Chap. 119).

Not uncommonly, body hair increases in pregnant women, particularly during the first trimester; usually this condition resolves after delivery.

Some women with acromegaly are hirsute, as are some women with prolactinomas. Hypothyroidism, particularly in the young, may be associated with an increased growth of whorls of lanugo-like hair on the back. Women with anorexia nervosa (see Chap. 128) also may have large amounts of fine lanugo-like hair on the face, back, and shoulders.63a Porphyrin due to congenital erythropoietic porphyria, porphyria cutanea tarda, or toxic porphyria (see Chap. 235) is commonly associated with hypertrichosis. Certain extremely rare 46,XY individuals with ambiguous genitalia have been reared as females because of androgen-resistance syndromes (see Chap. 90); these persons may present in the peripubertal period as hirsute females. In congenital lipoatrophic diabetes (Berardinelli-Seip syndrome), the lipodystrophy may be accompanied by hirsutism and occasionally by hyperhidrosis. In many of these conditions, the primary suspected diagnosis can be established from the history and physical examination findings.

During history-taking, the patient may volunteer that she has been exposed to diethylstilbestrol (DES). Epidemiologically, DES exposure has been shown to be associated with hirsutism, although no direct cause has been established.

CUSHING SYNDROME

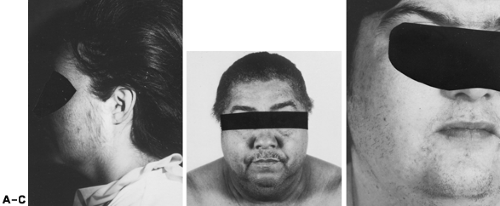

Rarely, persons with Cushing syndrome present with hirsutism; other signs and symptoms usually predominate. Nevertheless, hirsutism is commonly present. In addition to increased terminal hairs, long, silky hair may be present on the face and extremities (Fig. 101-14). If this diagnosis is considered, an overnight dexamethasone-suppression test or urinary free cortisol assay are useful screening measures (see Chap. 75).

NEOPLASIA AND HYPERANDROGENISM

An important reason for evaluating patients with androgen excess is to rule out neoplasms of the ovary or, less commonly, the adrenal gland. Measurement of blood levels of androgens and careful history-taking are of great importance. A history of sudden onset and rapid progression of the signs and symptoms in a previously asymptomatic woman is ominous. With rapidly increasing concentrations of androgens, defeminization usually occurs first: a decrease in breast size, a change in body contour, and menstrual disturbances precede acne and progressive hirsutism. Virilization is encountered because virtually all tumors secrete sufficient androgen to cause this finding. In the workup of a patient with hirsutism, a pelvic examination always should be performed.

Ovarian Tumors.

Any ovarian neoplasm can produce androgen (see Chap. 102). Benign serous cysts and other nonfunctional tumors can cause excessive androgen production by stimulating the adjacent thecal-stromal tissue. The most frequently encountered functional tumors are the Sertoli-Leydig cell type (i.e., arrhenoblastoma), lipoid cell tumors, and hilus cell tumors (see Fig. 101-14). In premenopausal women, most tumors (e.g., arrhenoblastomas) become unilaterally palpable on pelvic bimanual examination. Functional ovarian tumors typically are unilateral masses.

In postmenopausal women, ovarian tumors often are small and not palpable. Any palpable ovary in this age group is of great concern. When the history is suggestive, attention is focused on the levels of serum testosterone. Most ovarian neoplasms are associated with serum testosterone levels above 200 ng/dL. However, because of episodic variation, some neoplasms are associated with serum testosterone levels between 150 and 200 ng/dL.64 When androgen levels are in this range, tumor is a far less frequent diagnosis than in some other functional states, but the patient still requires thorough evaluation. Suppression and stimulation tests are unreliable for the diagnosis of an ovarian neoplasm.

Even the use of a GnRH agonist, which causes down-regulation of gonadotropins and ovarian suppression, has been shown to suppress androgen secretion in ovarian tumors.65

Nonsteroidal markers of ovarian tumors can also be evaluated but generally are of limited utility. Some Sertoli-Leydig–cell

tumors produce α-fetoprotein, and these tumors are often malignant. In these patients, measurements of α-fetoprotein may be useful in detecting recurrence and metastases.66 Some granulosa-cell tumors produce androgens; in these tumors, circulating levels of inhibin are elevated and may be measured in postoperative follow-up.67 Because pelvic examination may be difficult, especially in obese women (50% of patients with ovarian masses are obese), vaginal ultrasonography may be helpful to differentiate a unilateral mass.68 Bilaterally enlarged ovaries are reassuring and suggest polycystic ovaries. With vaginal ultrasonography, the color flow Doppler technique has been helpful in diagnosing small ovarian tumors by measuring increased blood flow through the mass. If no ovarian mass is found and serum testosterone levels are >150 ng/dL, computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the adrenal should be performed. Rarely, a testosterone-secreting adrenal adenoma may be encountered. CT has limited value in the diagnosis of ovarian tumors,69 but MRI may be useful for identifying small, solid ovarian tumors.69 Iodomethylnorcholesterol scanning may also be useful and has been able to identify some small ovarian tumors.70 Finally, if the results of these techniques are negative, selective venous catheterization studies should be considered but are dependent on the experience of the angiographer.

tumors produce α-fetoprotein, and these tumors are often malignant. In these patients, measurements of α-fetoprotein may be useful in detecting recurrence and metastases.66 Some granulosa-cell tumors produce androgens; in these tumors, circulating levels of inhibin are elevated and may be measured in postoperative follow-up.67 Because pelvic examination may be difficult, especially in obese women (50% of patients with ovarian masses are obese), vaginal ultrasonography may be helpful to differentiate a unilateral mass.68 Bilaterally enlarged ovaries are reassuring and suggest polycystic ovaries. With vaginal ultrasonography, the color flow Doppler technique has been helpful in diagnosing small ovarian tumors by measuring increased blood flow through the mass. If no ovarian mass is found and serum testosterone levels are >150 ng/dL, computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the adrenal should be performed. Rarely, a testosterone-secreting adrenal adenoma may be encountered. CT has limited value in the diagnosis of ovarian tumors,69 but MRI may be useful for identifying small, solid ovarian tumors.69 Iodomethylnorcholesterol scanning may also be useful and has been able to identify some small ovarian tumors.70 Finally, if the results of these techniques are negative, selective venous catheterization studies should be considered but are dependent on the experience of the angiographer.

Further assessment of any virilized postmenopausal woman is mandatory, regardless of the serum androgen levels. Occasionally, a postmenopausal woman with an androgen-producing ovarian tumor complains only of postmenopausal bleeding, and virilization may not be obvious.71

Adrenal Tumors.

Adrenal adenomas and carcinomas may produce any or all of the steroids normally produced by the adrenal; attention should be directed to symptomatic signs of glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid excess (see Chap. 75). Except for the testosterone-producing adenoma, an adrenal neoplasm virtually never is encountered with DHEAS levels <8 μg/mL. If serum DHEAS levels are >8 μg/mL, the differential diagnosis usually is between neoplasm and one of the enzymatic deficiencies causing congenital adrenal hyperplasia72 (see Chap. 77).

The patient’s history is important. Adrenal carcinomas often are debilitating and rapidly progressive. The history of the adult forms of congenital adrenal hyperplasia begins with peripubertal menstrual disturbances and hirsutism that is not rapidly progressive. Even the testosterone-producing adenomas lead to elevated serum levels of DHEAS, although these levels usually are between 3 and 5 μg/mL. In the presence of androgen excess, CT of the adrenal gland is the most sensitive diagnostic test for a neoplasm. Small lesions (1–2 cm) may be demonstrated. Lesions as small as 5 mm may be detected.73 However, if the index of suspicion for congenital adrenal hyperplasia is high, initial screening tests for congenital adrenal hyperplasia may be performed first.

IDIOPATHIC HIRSUTISM

Idiopathic hirsutism is perhaps the most common diagnosis in patients presenting with excessive hair. Other causes of hirsutism should be excluded.Idiopathic hirsutism includes conditions that have been called familial. Among whites, it is more common in women of Mediterranean ancestry. The diagnosis is most often made in women who have no menstrual complaints yet have hirsutism that cannot be explained on the basis of their normal serum levels of testosterone and DHEAS. Serum free or non–SHBG-bound testosterone levels should be normal.31

In spite of its name, nothing is idiopathic about this disorder in most patients. A subtle or even obvious source of increased androgen production may be documented.74,75 Even if no signal-related disturbances are seen, skin sensitivity or a disorder of the peripheral compartment more than adequately explains the hirsutism12,76 (Fig. 101-15). High levels of serum 3α-diol G and genital skin 5α-RA are common in patients with idiopathic hirsutism12,76 (Fig. 101-16). Moreover, peripheral androgen production (e.g., serum 3α-diol G) correlates well with the Ferriman-Gallwey score.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree