Chapter 48 Herpes Simplex Virus Infections

PATHOGEN

Herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) and type 2 (HSV-2) are common pathogens in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected patients. Seroprevalence surveys of adults in the United States indicate that 50–70% of individuals are infected with HSV-1 and 15–33% with HSV-2.1–3 HSV-2 is one of the most prevalent sexually transmitted viruses in the world. It is estimated that 50 million individuals have genital HSV infection. Genital HSV is more common in women (one in four American women) than in men (one in five American men).4 An even higher prevalence of HSV-2, in some cases as high as 75%, has been estimated in some developing countries.5 HSV-2 is an important public health issue worldwide due to its increasing prevalence and the fact that it has been shown to be an important cofactor in HIV transmission.6 One study of discordant couples in Uganda showed that HSV-2-infected, HIV-negative partners had a fivefold increased risk of acquiring HIV per sexual contact, compared with HSV-2-negative partners.7

There are increased seroprevalence rates for both HSV-1 and HSV-2 in HIV-infected persons.8 A European study of HIV-infected women found antibodies to HSV-1 and HSV-2 in 76% and 42%, respectively.9 Eighty percent of HIV-infected South-African teenagers are estimated to be HSV-2 seropositive.10 Similarly ∼80% of HIV1 men who have sex with men (MSM) in the US are estimated to have genital HSV infection.11

In the era prior to the widespread use of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) 4.4% of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS)-defining illnesses in HIV-infected patients were due to severe HSV-1 or HSV-2 infection.12 Several studies have shown that there is an increased incidence of HSV-related genital ulcer disease in HIV-infected women compared to HIV-infected men.12–15 It has been noted that the overall incidence of clinically evident HSV infection in HIV-infected patients has declined, associated with the increased use of HAART.16 Nonetheless, HSV disease continues to cause significant morbidity in HIV-infected individuals. Recent studies have demonstrated that HSV outbreaks may be associated with increased HIV replication as measured by plasma HIV RNA however these increases may be muted in patients who are on HAART. Some investigators suggest that treatment of HSV in persons co-infected with HSV and HIV could lead to delayed HIV disease progression and decreased HIV transmission particularly in settings where HAART availability is limited.17,18 Clinical trials to evaluate this hypothesis are ongoing.

Herpes simplex virus has a double-stranded DNA enclosed in an icosahedral capsid that is surrounded by a lipid envelope. The most characteristic biologic property of these viruses is the ability to induce latency and periodically reactivate infection.19,20 The incubation period is 2–12 days. Spread is person to person via contact with infected body secretions. Primary infection occurs following initial introduction of the virus through the skin or mucous membranes. Following local replication, the virus travels along the sensory nerves and establishes latency in the dorsal nerve root ganglia. Reactivation disease occurs when the virus travels back along the sensory nerves and replicates in the mucocutaneous region that was initially infected. Although reactivation disease is generally of shorter duration and consists of milder symptoms than primary infection, it should be noted that both primary and reactivation infections are often clinically asymptomatic.19,20

The most common clinical manifestation of HSV is the development of vesicular and ulcerative lesions in the orolabial and/or genital regions. HSV-1 is associated with ∼70% of orolabial infections and HSV-2 with ∼70% of genital infections. Symptoms are more severe and prolonged in HIV-infected patients with advanced disease than in immunocompetent patients.19–23 Symptoms begin with painful, erythematous papules that quickly become vesicles and soon ulcerate. These ulcerations then crust and heal. In the untreated healthy host, the time course from the development of papules to healing is ∼14–28 days for primary disease. The course of reactivation disease is considerably shorter. Painful, tender regional lymphadenopathy often accompanies these lesions, particularly in patients with primary infection.10,11

In HIV-infected patients, most morbidity is associated with HSV infections in the genital and perirectal region.21–23 While some “initial outbreaks” represent the first symptomatic episode of recurrent disease in previously asymptomatic individuals, the first clinical presentation of HSV may be an indicator of unsafe sexual practices thus should warrant safer sex counseling. Most serious infections occur in patients with less than 200 CD4 cells/mm3. Untreated, the time course of HSV is often prolonged. Ulcerative lesions are often present for more than 1–3 months. In patients with advanced HIV infection, recurrences become more frequent, severe, and prolonged if left untreated. Multiple ulcerations can become confluent and involve extensive areas of the perineum. Heaped-up verrucous lesions caused by HSV-2, resembling condyloma acuminata, have been reported.24 Asymptomatic shedding of HSV-2 is more frequent and more prolonged in both HIV-infected men and women compared to HIV-uninfectedpatients.25,26 Risk factors for increased HSV-2 shedding among HIV-infected men were low CD4 cell count and serum antibodies to both HSV-1 and HSV-2 compared to HSV-2 alone.26 Notably asymptomatic shedding of HSV virus is still frequent in HIV-infected individuals who are treated with HAART despite the fact that clinical HSV outbreaks are less frequent.27

Proctitis caused by HSV is the most common cause of nongonococcal proctitis in MSM. It has been described primarily in HIV-infected male patients.28–30 They usually present with fever, pruritus, rectal pain, and tenesmus. A rectal discharge or hematochezia may be present. Additionally, difficulty urinating, impotence, and the presence of sacral paresthesia may be present. External lesions and inguinal lymphadenopathy frequently accompany this syndrome. Sigmoidoscopy shows large ulcerations. Concomitant infection with Neisseria gonorrhoeae has also been noted.28–30

As with genital and perirectal disease, orolabial HSV infections are more severe and prolonged in HIV-infected patients.23,31 Lesions can occur on any mucosal surface, most commonly the lips, palate, or gingiva. Most cases are reactivated disease and most commonly consist of one or two ulcerations. Co-infection with other pathogens such as cytomegalovirus (CMV) or Histoplasma has been reported.32

Mucocutaneous forms of HSV infection located in other parts of the body, such as herpetic whitlow or paronychia, have been reported in association with HIV infection.33–35 As is the case for disease in the genital and orolabial regions, cutaneous disease can be more severe and prolonged than that seen in the immunocompetent host.

After mucocutaneous disease, the next most common clinical manifestation of HSV infection in HIV-infected patients is HSV esophagitis.36–39 This AIDS-defining complication is seen usually in patients with less than 50 CD4 cells/mm3. The symptoms are clinically indistinguishable from esophagitis caused by Candida species. Odynophagia or burning retrosternal pain is common. Orolabial ulcerations are present in 38–80% of patients with HSV esophagitis.36–38 Endoscopically, most herpetic lesions are seen in the distal third of the esophagus.36 Rare complications include esophageal strictures and perforation.39,40

Visceral or disseminated HSV infection in HIV-infected patients is uncommon. Case reports of hepatitis, pneumonia, or encephalitis have been noted. Most cases of HSV encephalitis are caused by HSV-1 and can be difficult to distinguish clinically from other causes of encephalitis such as CMV infection and toxoplasmosis particularly in patients with advanced HIV disease.41 In immunocompetent patients, herpes simplex encephalitis usually occurs in the temporal lobe, whereas, in HIV-infected patients encephalitis has involved diverse areas of the brain outside the limbic system as well as the brain stem.41 Myelitis caused by HSV has also been reported.41

DIAGNOSIS

Mucocutaneous vesicular ulcerative disease in patients with HIV infection can have multiple causes, including disseminated CMV, varicella-zoster virus (VZV), or disseminated cryptococcal infection; histoplasmosis; squamous cell carcinoma; or pustular dermatosis. Therefore it is important to establish a firm microbiologic diagnosis, particularly if a typical-appearing lesion does not respond to acyclovir (Fig. 48-1). The laboratory diagnosis of HSV includes culture, cytopathologic techniques, HSV antigen detection by immunologic methods, nucleic acid detection by polymerase chain reaction (PCR), and serology. Traditionally, a viral culture has been the cornerstone of the laboratory diagnosis of HSV. Specimens are most likely to yield virus if they are taken from vesicles within the first 1–2 days after formation.19,42 Specimens for culture should be obtained from an unroofed vesicle or the base of an ulcer using a dacron tipped catheter. Contamination with stool, urine or blood should be avoided as these may lead to falsely negative results. Following inoculation into tissue culture, a cytopathic effect with ballooning degeneration and multinucleated giant cells occurs within 1–2 days. Typing for HSV-1 or HSV-2 can be done using type-specific monoclonal antibodies, although this is not important for therapy.19,20,42 Viral isolation is especially important if acyclovir resistance is suspected because viral susceptibility testing can be performed.43

Cytopathologic examination of scrapings of ulcerations can be quickly performed. The Tzanck smear shows typical multinucleated giant cells characteristic of herpesvirus infection but does not differentiate HSV from VZV.19,20,42 Additionally, it is not as sensitive as a culture, with a positivity rate of ∼40–50%.

Direct identification of HSV antigens (by immunofluorescence or immunoperoxidase techniques) on the surface of cells obtained from a suspicious lesion is a newer diagnostic method suitable for the rapid diagnosis of HSV infection in clinic settings. These tests are available via commercial labs and tend to be less expensive than viral culture or PCR. The sensitivity and specificity of these assays varies from 80% to 98% and 96% to 99% respectively.4,44

Sensitive type-specific serologic tests have been developed,45 but detecting antibodies to HSV-1 or HSV-2 has no role in the diagnosis of active vesicular ulcerative disease. It does provide specific information as to whether the patient has been previously infected with the virus.

Multiple methods for in vitro antiviral susceptibility testing of HSV have been described including a quantitative real-time PCR (TaqMan) assay and a colorimetric yield reduction assay, ELVIRA (enzyme-linked virus inhibitor reporter assay).43,46–48 While routine use of susceptibility testing is not indicated for the management of uncomplicated episodes of HSV disease, the availability of rapid tests may be helpful for management of episodes that appear to be unresponsive to acyclovir therapy (Fig. 48-1).

TREATMENT

Mucocutaneous Disease

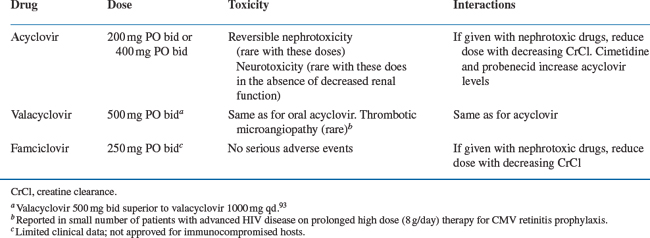

The treatment for primary infection is oral or intravenous acyclovir (Table 48-1). Therapy is given for a 7–10 day course or until the lesions have become crusted over. It has been suggested that HSV proctitis may require higher and/or more prolonged dosing but comparative studies are not available. Alternative agents are famciclovir or valacyclovir. In patients with severe disease or who are unable to tolerate or absorb oral medications, intravenous acyclovir (5 mg/kgevery 8 h) should be used. The treatment course is 7–10 days or until the lesions have crusted over. Patients can be switched to oral acyclovir to complete the course of therapy when they are clinically improved and able to tolerate oral medications.49–52

Recurrent disease treatment is individualized to the patient’s needs. Episodic therapy is usually patient-initiated. The treatment of choice in this instance is also acyclovir. Alternate agents include famciclovir 500 mg PO twice daily or valacyclovir 500 mg PO twice daily.50,53,54 A comparative study in HIV-infected patients with mucocutaneous HSV infection of famciclovir (500 mg PO twice daily) and acyclovir (400 mg PO five times a day) showed that there was no difference between these agents in decreasing the time to complete healing and reducing new lesion formation.55 It should be noted that the dosage of famciclovir that was used in this trial was higher than the dosage used to treat HIV-uninfected patients, which is 125 mg PO twice daily. Studies in HIV-infected patients treated with this lower dosage have not been reported; and whether this lower dose would be equally efficacious in HIV-infected patients, particularly those with less immunosuppression, is unclear. In general, recurrent infection is treated for 5–10 days. In patients with advanced HIV infection, improvement may take up to 14 days.

Continuous suppressive therapy should be considered for patients who have frequent symptomatic recurrent infections (Table 48-2). Frequent recurrences are usually defined as three or more outbreaks during a 6-month period. Acyclovir given at a dose of 400–800 mg PO two or three times daily is the treatment of choice for suppressive therapy.4 Alternative agents include famciclovir 250 mg PO twice daily and valacyclovir 500 mg PO twice daily or 1000 mg PO once daily.4,56 Suppressive therapy with valacyclovir compared to placebo was associated with a 2.5-fold reduction in recurrent HSV genital HSV episodes in a study in 293 HIV-infected subjects. Valacyclovir was well tolerated with adverse event rates similar to placebo.57 Optimization of HAART may decrease the need of continuous suppressive therapy and should form an important component of this therapeutic strategy.

Table 48-2 Chronic Suppressive Treatment for Recurrent Herpes Simplex Virus Disease in Patients with HIV Infection

Although there has not been an increase in acyclovir resistance in immunocompetent patients treated with prolonged courses of acyclovir (>6 years of therapy), there have been increasing reports of acyclovir resistance in patients with advanced HIV infection.43,58,59 A study of patients 18 years or older with suspected genital HSV who attended 22 sexually transmitted disease (STD) and HIV clinics in the US between October 1996 and April 1998 revealed acyclovir resistant virus in 0.18% (three of 1644) HIV-negative patients and 5.3% (12 of 226) HIV-positive patients. Risk factors for HSV resistance included the use of oral and topical acyclovir, the duration of the current episode, a history of recurrent genital herpes, and a low CD4 cell count.60 Treatment of HIV-infected patients with recurrent HSV disease with episodic therapy rather than continuous suppression has been advocated as a way to decrease exposure to acyclovir. Whether this reduces the likelihood of acyclovir-resistant disease has not been established.

Acyclovir-Unresponsive Disease

Although the overall incidence of acyclovir resistance remains low, there have been reports of HIV-infected patients with severe debilitating chronic mucocutaneous disease caused by acyclovir-resistant HSV.33,43,61,62 Additionally, patients with esophagitis and visceral disease caused by acyclovir-resistant HSV have been described.43,63,64 Typically, these patients have advanced HIV disease with less than 50 CD4 cells/mm3. The patients with mucocutaneous disease have large, progressive, deeply ulcerated lesions that frequently develop satellite lesions. Symptoms can be present for months. Additionally, viral shedding is prolonged.43,61,62

Acyclovir resistance should be suspected in HIV-infected patients with mucocutaneous HSV infections that do not respond to acyclovir therapy within 14 days (Fig. 48-1). At this time, repeat cultures should be performed and the HSV isolate should be saved for antiviral susceptibility testing. Not all patients with HSV infection unresponsive to oral acyclovir have acyclovir resistance. Therefore patients should first be treated with higher doses of acyclovir (800 mg PO every 4 h five times per day). Alternatively, famciclovir or valacyclovir, which have enhanced oral bioavailability, may be tried (Fig. 48-1; Table 48-1). Continuous-infusion acyclovir (1.5–2.0 mg kg−1 h−1) has also been reported to be beneficialfor treatment of acyclovir-resistant HSV.65,66 If these regimens fail, antiviral susceptibility testing can be performed and alternative therapy considered. Treatment of acyclovir-resistant HSV is with foscarnet43,50,60,67–70 given intravenously at a dose of 40 mg/kg three times daily (Table 48-3). Treatment is continued until the lesions have crusted over and reepithelialized, which usually takes at least 2–3 weeks. It is interesting that following resolution of lesions caused by acyclovir-resistant HSV, recurrent infections often are caused by HSV isolates sensitive to acyclovir. This indicates that latent infection may be maintained by a virus population different from that found in the acute, cutaneous lesions.68

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree