Chapter 4

Hereditary Cancer

What’s Swimming in Your Gene Pool?

MUCH OF YOUR APPEARANCE results from traits you inherit from your parents. You can thank them for your cute dimples, stubby fingers, or widow’s peak. These inherited characteristics are written into your DNA. You can pass them—and genetic mutations—on to your sons and daughters.

Mutations from Mom or Dad

All of us in the human race get half our genetic material from each parent. So it’s equally possible to inherit a BRCA mutation from Mom or Dad. In fact, if we could identify every person with a BRCA mutation, we would find about half received their mutation from their father and half from their mother. If either of your parents has a BRCA mutation, you and each of your siblings have a 50 percent chance of inheriting it. Likewise, each of your children has the same 50 percent chance of inheriting your mutation and high cancer risk. Generally, children who don’t inherit your mutation have average cancer risk.

Probability of inheriting a mutation from one parent

Inheriting Multiple BRCA Mutations

While uncommon, it’s possible to inherit mutations in both BRCA1 and BRCA2, especially if you’re of Ashkenazi Jewish ethnicity. People with double mutations are believed to have risk for breast, ovarian, and fallopian cancer that is similar to individuals with BRCA1 mutations. Risk for melanoma, pancreatic cancer, prostate cancer, and male breast cancer is thought to be equivalent to someone with a BRCA2 mutation. If you have mutations in both BRCA genes, or you and your spouse each have a mutation, your risk of passing one or both mutations to your children is 75 percent. Embryos can grow with a double mutation in the BRCA2 gene, but they must have at least one working copy of BRCA1 to survive. Children who inherit a mutation in both copies of BRCA2—one mutation from each parent—develop Fanconi anemia (FA), a rare and serious childhood disorder characterized by bone marrow that doesn’t produce enough blood cells. Several other genes are also linked with FA. Some children with this disorder have physical abnormalities such as altered skin pigment, deformed thumbs, a very small head size, or stunted growth. Other abnormalities in the heart, kidney, genitalia, or hearing may also develop. Blood abnormalities usually develop before age 12 and may include fatigue and paleness, bleeding or bruising, or susceptibility to infections from a low level of white blood cells.

Hidden Risk in the Family Tree

Sometimes it’s difficult to determine whether a mutation runs in a family. Lifestyle choices, a small family size, having few female relatives, or having relatives who died early from other causes may obscure familial cancers. In some cases, family history may not be available. Many Ashkenazi Jewish families, for example, cannot trace their family history beyond the Holocaust. If you were adopted and don’t know your family history, or your female relatives died before age 50 of unknown causes, a genetic counselor can help determine the likelihood that you inherited a mutation based on the information available.

MY STORY: My Mutation Came from My Dad

Diagnosed with breast cancer, I thought I had no relevant family history. My father’s first cousins had the disease; they were in their 60s and seemed like such distant relatives. I don’t recall a single health form ever asking about my father’s first cousin. After my diagnosis with breast cancer, I met with a genetic counselor who realized from my small family tree that my cancer likely came from my father’s side. If he had more women on his side of the family, we may have seen more breast cancer. Sure enough, like my two cousins, I tested positive for a BRCA2 mutation.

—ELLYN

HBOC and Other Hereditary Cancer Syndromes

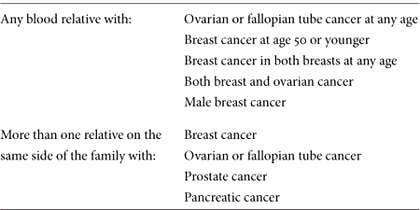

Hereditary cancer syndromes are caused by mutations that run in families and raise the risk of multiple cancers. BRCA mutations in a family cause hereditary breast and ovarian cancer (HBOC) syndrome, an inherited tendency for cancers of the breast, ovaries, fallopian tubes, pancreas, prostate, and skin. Several other cancer syndromes have been identified, each with a unique pattern of disease. Your family may have a hereditary cancer syndrome if multiple relatives have had certain types of cancers, including rare cancers; if the same cancer appears in more than one generation; or if cancers were diagnosed at a young age. One or two cases of the same types of cancer within a family—these days that includes many families—don’t necessarily indicate a cancer syndrome. Any of the signs shown in table 5 may indicate that HBOC runs in the family.

Table 5. Signs of HBOC within a family

Although HBOC is the most common cause of hereditary breast and ovarian cancer, inherited syndromes caused by mutations in other genes also increase the risk for these cancers.

Lynch Syndrome

Hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer, also known as Lynch syndrome, increases risk for colon, uterine, and ovarian cancers. Women with Lynch syndrome have greater risk for ovarian cancer than other women, but less risk than someone who has a BRCA mutation. Caused by a mutation in one of several specific genes, Lynch syndrome is the most common hereditary cause of colon cancer, accounting for about 5 percent of all cases. If you have Lynch syndrome, you need regular screening at an early age—colonoscopy beginning between ages 20 and 25 is recommended—because you have a high risk for benign polyps that can develop into colon cancer if they’re not removed during colonoscopy. Lynch syndrome may run in families in which a relative has been diagnosed with colorectal cancer more than once, when colorectal cancer or uterine cancer occurs in two successive generations in relatives age 50 or younger, or when three relatives have any of the cancers related to Lynch syndrome.

Cowden Syndrome

Cowden syndrome results from an inherited mutation in the PTEN tumor-suppressor gene. Even individuals who have no family history may develop the syndrome spontaneously. One in 200,000 people is estimated to have Cowden, with a risk of developing breast cancer as high as 50 percent.1 Similar to individuals with BRCA mutations, diagnosis before age 50 may be more common. Only a small percentage of breast cancers are attributed to Cowden syndrome (it may be underdiagnosed). Having Cowden syndrome also ups the chance for other cancers, including thyroid (10 percent risk), endometrial (5 to 10 percent risk), and cancers of the kidney, colon, and skin (risk levels unknown). It’s sometimes the underlying cause of otherwise unexplained cancers in families that test negative for a BRCA mutation.

Gene testing can identify this syndrome. It takes an experienced genetics expert to evaluate a family’s unexplained cancers and determine if Cowden syndrome may be the culprit. Men and women with Cowden’s have a higher-than-normal risk for both benign and cancerous growths including thyroid tumors; lesions of the skin, mouth, and lower digestive tract; and genital or uterine fibroids. Some studies have also linked PTEN mutations with melanoma and certain types of aggressive brain tumors. Other signs of this syndrome within a family are visible benign growths, such as lipomas (fatty lumps) or goiter (benign growth of the thyroid); polyps; hamartomas (benign masses); skin tags; fibrocystic breast changes; and intestinal polyps.

Li-Fraumeni Syndrome

Li-Fraumeni syndrome is caused by a rare inherited mutation in the P53 gene. This syndrome often causes childhood and adolescent cancers and carries a 50 to 80 percent risk of breast cancer between ages 15 and 44.2 Individuals who have Li-Fraumeni often develop childhood cancers of the bone, soft tissue, adrenals, brain, stomach, and other organs.

Hereditary Diffuse Gastric Cancer Syndrome

Hereditary diffuse gastric cancer (HDGC) syndrome results from a mutation in the CDH1 gene. Little is known about HDGC. It can cause stomach cancers, often before age 40 (most gastric cancers in the general population are diagnosed after age 60). Women with an HDGC mutation have a 39 to 52 percent lifetime risk of developing lobular breast cancer.3

Peutz-Jeghers Syndrome

Peutz-Jeghers syndrome occurs from a mutation in the STK11 gene. Patients with this syndrome have elevated risk for breast and ovarian cancer, as well as cancer of the cervix, pancreas, and gastrointestinal tract. Children with Peutz-Jeghers often develop small dark freckles on the face, hands, feet, and anus that usually fade as they become teenagers. Thousands of polyps in the stomach and intestines are common in individuals with Peutz-Jeghers. It’s a rare syndrome, and experts aren’t sure how frequently it occurs.

Ataxia-Telangiectasia

Ataxia-telangiectasia (AT) is a rare disorder affecting only 1 in 100,000 births. It’s believed to cause immune system cancers, including leukemia and lymphomas. Only individuals who inherit ATM gene mutations from both parents develop AT—but having a single mutation may predispose individuals to greater chance of developing breast cancer.

CDKN2A mutations

Mutations in the CDKN2A gene are also very rare. People who inherit this mutation have up to a 17 percent lifetime risk of pancreatic cancer and a 28 percent lifetime risk for melanoma.4

Plotting Your Genetic Pedigree

If your family has been affected by cancer, you’ve probably wondered about your own risk. A genetics expert can evaluate your family’s pattern of disease to determine whether a mutation or hereditary cancer syndrome exists in your family, and whether you or a relative should consider genetic testing. First, you’ll need to gather information to document your family’s pedigree, or medical history. This document shows all your relatives, their relationship to you, and any diseases they’ve had. With this information, a genetic counselor can identify health patterns and determine your risk for inherited disease. Your pedigree can’t predict your future health, but it can give you an insight your relatives never had: a peek into your future and the potential to change your fate by determining which diseases you’re predisposed to develop.

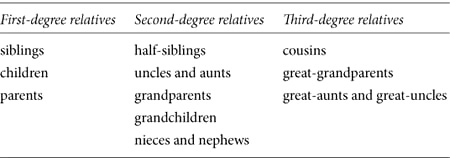

Ideally, a genetics expert needs information from both sides of the family for three generations to determine whether a hereditary cancer pattern exists. So if possible, you’ll need to collect information about your first-, second-, and third-degree biological relatives (see table 6).

Table 6. Gather information about three generations

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree