Chapter 55 Hepatitis C Infection

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected persons have an increased incidence of hepatitis C and an accelerated course of chronic liver disease, leading to a relatively high incidence of liver-related morbidity and mortality in the era of highly effective antiretroviral therapy (ART). Accordingly, the US Public Health Service (USPHS), Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA), American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the European Consensus panel have published guidelines on the management of HCV infection in persons with HIV.1–4 In this chapter, the pathogen, epidemiology/natural history, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention are discussed. Emphasis is placed on clinical issues of greatest importance to the HIV-infected patient.

PATHOGEN

The hepatitis C virus (HCV) is a spherical, enveloped RNA virus, classified within the Hepacivirus genus of the Flaviviridae family. The positive-sense, single-stranded, ∼9.6-kb RNA genome contains a single large (,3000-amino acid) open reading frame flanked by 3 + 9 and 5 + 9 untranslated regions.5 The open reading frame encodes for at least 10 proteins including four structural proteins (core protein, envelope proteins E1 and E2, NS2A) and six nonstructural proteins (cis-active Zn2 + 1-dependent proteinase, serine proteinase, NTPase, RNA helicase, NS3 proteinase cofactor and RNA-dependent RNA polymerase).

Replication of HCV chiefly occurs in the cytoplasm of hepatocytes, although some studies have suggested that replication may occur in some other cell types, such as B cells, T cells, and monocytes. In chronically infected humans, mathematic models of HCV kinetics suggest that up to 1.0 × 1012 virions are produced daily with a half-life of ∼2.5 h.6 This high level of virion turnover coupled with the lack of proofreading by the RNA polymerase results in the rapid accumulation of mutations, estimated at a rate of 0.90 × 1023 1.92 × 1023 base substitutions per year.7,8 Consequently, within each infected person, HCV exists as a quasispecies, a group of closely related variants that typically share 91–99% sequence identity. HCV sequences from different individuals may have less than 60% RNA identity, and six major genotypes have been identified.9 HCV strains are further classified into subtypes that typically share 75–85% nucleotide sequence identity.10,11 Although the natural history of HCV genotypes does not seem to vary, there are dramatic intergenotypic differences in responsiveness to interferon-based therapies.

EPIDEMIOLOGY AND NATURAL HISTORY

Epidemiology

Hepatitis C virus is transmitted chiefly by percutaneous exposure to blood. Although transfusion of contaminated blood and blood products was once a major source of HCV transmission, HCV transmission by administration of clotting factors diminished in the United States and Europe during the mid-1980s because of viral inactivation procedure and use of recombinant products.12 In addition, during the early 1990s when blood donations were routinely screened for HCV antibody, the incidence of post-transfusion HCV infection dropped to less than 1:100 000 per unit transfused in the United States.13 After 1999 the risk of transfusion transmission of HCV declined even further (1:1.8 million per unit transfused) because of routine screening of donations for HCV RNA.14 Injection drug use is the leading route of HCV transmission in the United States. Indeed, worldwide, 50–90% of injection drug users are HCV infected as a consequence of sharing contaminated needles and drug-use equipment.12,15,16

The HCV can also be transmitted between sexual partners and from mother to the infant.17 A higher than expected HCV prevalence is frequently found in persons reporting high-risk sexual practices (e.g., multiple sexual partners), and 15–20% of persons with acute hepatitis C have an anti-HCV-positive partner or admit having had multiple sexual partners during the 6 months before illness onset, in the absence of other risk factors for infection.18 In addition, in one study women attending a clinic for sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) were threefold more likely to have HCV infection if their sexual partner was HCV infected.19 On the other hand, in at least five studies the prevalence of HCV infection was less than 2% among long-term sexual partners of HCV-infected individuals.20–24 Furthermore, a higher than expected prevalence of HCV infection has been found in only a few studies of men who have sex with men (MSM).25,26 However, recent reports suggest that HIV-infected men engaging in unprotected, traumatic sexual acts with other men may be at increased risk for the sexual transmission of hepatitis C.27–30 Taken together, although there is evidence that HCV may be transmitted sexually, heterosexual intercourse appears to be a relatively inefficient mode of transmission.

The HCV infection occurs in ∼2–5% of infants born to HCV-positive mothers.17 However, the incidence of mother–infant transmission increases approximately threefold if the mother is co-infected with HIV.31–33 In addition, in one study an increased rate of HIV transmission was found among infants born to mothers who were co-infected with HIV and HCV.34

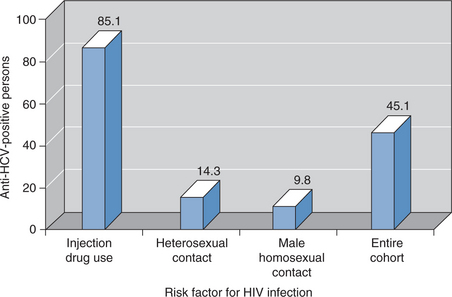

Because of shared routes of transmission, HCV and HIV co-infection is common. In the United States there are thought to be 150 000–300 000 persons co-infected with HCV and HIV, representing 15–30% of the estimated 1 000 000 individuals with HIV infection.35 Similar data have been reported from Europe; 33% of more than 3000 patients with HIV infection followed in the EuroSIDA cohort study had evidence of HCV infection.36 However, the prevalence of HCV/HIV co-infection varies depending on the route of HIV infection (Fig. 55-1). HCV is ∼10-fold more likely than HIV to be transmitted by an accidental needlestick exposure and is acquired more readily than HIV by injection drug users.37,38 Thus 50–90% of persons who acquire HIV from injecting drugs are also HCV infected. Similarly, more than 50% of hemophiliacs who were exposed to unscreened, nonheat-treated blood products had HCV/HIV co-infection.39 HCV infection is less common (,10%) in men who acquired HIV infection from same-sex intercourse.37,40

Natural History

After acute infection, ∼15% of individuals clear virus from the blood and presumably have fully recovered from infection.41,42 The remaining 70–85% of acutely infected persons have viremia that persists for life. In some chronically infected persons, alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels are persistently elevated or normal. However, in most persons they fluctuate and are poor predictors of liver disease.43 Some persistently infected persons develop hepatic fibrosis that progresses to cirrhosis, liver failure, or hepatocellular carcinoma.44 The probability of cirrhosis after 20 years of infection is estimated to be 5–25%, depending on the population studied.44–46 After cirrhosis has developed, the rates of progression to liver failure and hepatocellular carcinoma are estimated to be ∼2–4% and 1–7% per year, respectively.47

Unfortunately, disease progression for an individual patient cannot be predicted by currently available laboratory tests. The magnitude or the pattern of ALT elevation does not correlate well with disease outcome.48 Unlike the HIV RNA level, which is highly correlated with HIV disease progression, the HCV RNA level is not closely associated with the outcome of hepatitis C.41,49 The best tool for evaluating the stage of infection is liver biopsy, but even liver histology is an imperfect indicator of the ultimate disease course.50,51

HIV Infection Impact on Hepatitis C Progression

Infection with HIV has been reported to exacerbate several steps in the natural history of hepatitis C. First, HIV-infected persons were less likely to have cleared viremia than those without HIV.41,52 HIV infection has also been associated with a higher HCV RNA viral load and a more rapid progression of HCV-related liver disease.53–58 As early as 1993, Eyster and colleagues reported that HCV RNA levels were higher in people with hemophilia who became HIV infected than in those who remained HIV negative, and liver failure occurred exclusively in HIV/HCV-co-infected patients.56 More recently, among 1816 HCV-positive men with hemophilia who were prospectively monitored, Goedert and colleagues estimated the 16-year cumulative incidence of end-stage liver disease (ESLD) among men with and without HIV to be 14.0% and 2.6%, respectively.57 Furthermore, among those men with HIV/HCV co-infection, the ESLD risk increased 8.1-fold with HBsAg positivity, 2.1-fold with CD4+ T-lymphocyte cell counts below 200 cells/mm3, and 1.04-fold per additional year of age. Similarly, among HCV-infected persons who chiefly acquired HCV from injection drug use, Pol and co-workers found that HIV co-infection was an independent risk factor for the development of cirrhosis.58 Finally, the effect of HIV on HCV was summarized in a meta-analysis of studies by Graham and co-workers that assessed the correlation between HIV co-infection and the progression of HCV-related liver disease. HIV co-infection was associated with a relative risk of ESLD of 6.14 and a relative risk of cirrhosis of 2.07 when compared with HCV monoinfection.55

Given these data, and as survival among patients with HIV increases because of the use of potent antiretroviral therapies and prevention of traditional opportunistic pathogens, HCV-related morbidity and mortality among HIV-infected individuals can be expected to increase. Gebo and co-workers evaluated rates of admission at the Johns Hopkins University Hospital, Baltimore, Maryland, from 1995 to 2000 among HIV-infected patients and found that admissions for liver-related complications among HCV-positive patients increased nearly fivefold from 5.4 to 26.7 admissions per 100 person-years during that time.59 Similarly, among 23 441 HIV-infected North American and European patients followed in the Data Collection on Adverse Events of Anti-HIV Drugs (D:A:D) study, liver disease was the second leading cause of death, with an incidence of 0.23 cases per 100 person-years follow-up behind HIV/AIDS (0.59 cases per 100 person-years) and ahead of cardiovascular disease (0.14 cases per 100 person-years).60 Accordingly, in the era of potent ART, HCV-related liver disease is a major cause of hospital admissions and deaths among HIV-infected persons.

HCV Infection Impact on HIV Disease Progression

There are conflicting reports about the effect of HCV infection on the natural history of HIV disease. In a prospective study of 416 HIV seroconverters the 51.4% who were HCV co-infected had an HIV progression rate similar to those without HCV infection.61 Among 1742 patients, Sulkowski and co-workers found that HCV infection was not independently associated with progression to AIDS or death after adjusting for exposure to highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) and HIV suppression.37 Similarly, HCV infection was not associated with progression to AIDS or death after controlling for important confounding conditions among 10 481 HIV-infected individuals followed in 100 US centers or among 5957 HIV-infected patients observed in the EuroSIDA cohort.36,62 Conversely, Sabin and co-workers found that HIV/HCV-co-infected hemophiliacs with HCV genotype 1 infection experienced a more rapid progression to AIDS and death than did those infected with other genotypes.63 Among 3111 patients receiving potent ART, Greub and colleagues reported that HCV-infected persons had amodestly increased risk of progression to a new AIDS-defining event or death, even among the subgroup with continuous suppression of HIV replication.64

Interestingly, Greub and co-workers also found that the magnitude of the CD4+ T-lymphocyte cell increase following effective anti-HIV therapy was significantly less than that observed in HCV-uninfected persons, suggesting that HCV co-infection may blunt immune recovery following HAART.64 However, at least four other studies have failed to detect any significant impact of HCV infection on immunological or virological response to ART.36,37,62,65

HCV Co-Infection and HAART-Associated Hepatotoxicity

Antiretroviral drugs, such as zidovudine, nevirapine, and HIV-1 protease inhibitors, have been associated with hepatotoxicity, which may interrupt HIV therapy and cause significant morbidity and mortality.66–70 Some but not all studies suggest that drug-induced hepatotoxicity may be more common among patients with HIV/HCV co-infection, particularly with the use of HIV-1 protease inhibitors and antituberculosis drugs.71 The mechanism of enhanced drug-induced hepatotoxicity among co-infected patients is unknown but may be the result of underlying HCV-related liver disease or immune reconstitution with enhanced cytolytic anti-HCV immune activity.72–74 Although co-infected patients may be at increased risk for the development of hepatotoxicity, 88% of a large cohort of HCV-co-infected patients prospectively studied did not experience significant hepatotoxicity following HAART, and no irreversible outcomes were observed among the patients experiencing toxicity.68

Furthermore, recent studies suggest that the suppression of HIV replication and prevention or reversal of immunosuppression due to effective ART may be associated with decreased risk of liver disease progression and liver-related mortality. Indeed, Qurishi and co-workers found that ART significantly reduced long-term liver-related mortality among 285 patients followed for ∼10 years.75 In addition, several retrospective cohort studies have observed a decreased risk of cirrhosis among HIV/HCV-co-infected persons effectively treated with ART.76,77 Thus, the available evidence suggests that ARTs can be safely administered to HIV-infected patients with chronic hepatitis C; however, serum liver enzymes should be closely monitored in these patients. Although there are currently no established guidelines for the management of antiretroviral-associated hepatotoxicity, some studies have suggested that it is not necessary to discontinue ART unless patients are symptomatic or develop significant elevations in liver enzymes (>5–10 times the upper limit of the normal range).78

DIAGNOSIS

All HIV-infected persons should be screened for HCV infection because of the high prevalence of HCV infection in this group.3 HCV screening should be done with enzyme immunoassays (EIA) licensed for the detection of antibody to HCV in blood.79 Patients with positive anti-HCV results by EIA should have confirmatory testing performed using assays to detect HCV RNA such as reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR).1 The detection of HCV RNA in a person with a positive anti-HCV result indicates current infection. However, because some persons with chronic HCV infection experience intermittent viremia, a single undetectable HCV RNA result must be interpreted cautiously. Anti-HCV titers may decline to undetectable levels in persons with advanced immunodeficiency (CD41 T-lymphocyte count + <100/mm3).80 Likewise, in patients with acute HCV infection, anti-HCV EIA may remain undetectable for weeks.81 Thus HCV RNA should be assessed in the blood when HCV infection is suspected in persons with negative anti-HCV results. The clinical significance of quantitative HCV RNA level (i.e., viral load) in HIV-infected patients is not known and should not be interpreted based on the well-described relation of HIV viral load and HIV disease progression.82

MANAGEMENT

All HIV-infected individuals with chronic HCV infection should be counseled to prevent liver damage and HCV transmission and should be evaluated for chronic liver disease and considered for anti-HCV treatment (Table 55-1). Because alcohol ingestion, particularly in quantities of more than 50 g (four drinks) per day, accelerates the progression of liver disease and significantly increases the risk of cirrhosis, all HIV/HCV-infected patients should be advised to abstain from alcohol use.4,77,83 Counseling regarding household and sexual practices to prevent HIV transmission also should be effective to prevent HCV transmission.

Table 55-1 Strength of Evidence for Recommendations for the Management of HCV in HIV-Infected Patients1

| Recommendation | Strength of Evidencea |

|---|---|

| Grade III | |

| Grade III | |

| Grade III | |

| Grade III | |

| Grade III | |

| Grade III | |

| Grade III |

a Quality of evidence on which the recommendation is based: I, randomized, controlled trials; II-1, controlled trials without randomization; II-2, cohort or case-control analytic studies; II-3, multiple time series, dramatic uncontrolled experiments; III, opinions of respected authorities, descriptive epidemiology.

The HIV-infected patients with chronic HCV infection who are susceptible to hepatitis A virus (HAV) or hepatitis B virus (HBV) infections should be vaccinated because most of these patients have risk factors for acquiring HAV and HBV infection.17 In addition, HCV-infected patients with chronic liver disease who become infected with HAV are at increased risk for fulminant hepatitis.84

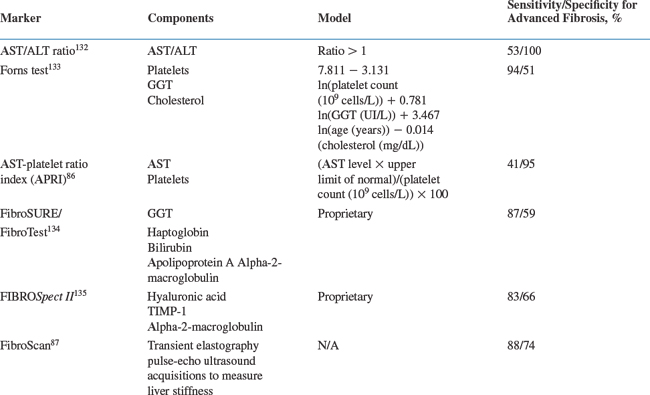

The HIV/HCV-co-infected patients should be evaluated for the presence of chronic liver disease. Assessments of disease severity should include a history and physical examination to look for signs and symptoms of chronic liver disease, measurement of blood albumin, prothrombin time, direct bilirubin assay, and platelet count to determine hepatic function; evaluation of liver histology by biopsy is appropriate in many patients. Measurements of the serum ALT level and HCV RNA level are important to establish that the infection is ongoing, but these tests provide only limited information regarding HCV disease severity. The liver biopsy provides important information about HCV-related disease activity and fibrosis stage and may exclude alternative causes of liver disease. Most studies indicate that liver biopsy can be safely performed in HIV-infected individuals.85 However, liver biopsy is an expensive and invasive procedure and may be difficult to perform in many settings where HIV-infected persons are encountered. Accordingly, noninvasive tests for determining liver disease stage have been developed and, despite limited validation data, are increasingly used to evaluate viral hepatitis-related liver disease (Table 55-2).29,66,86–92

Treatment

In mid-2007, the standard treatment for hepatitis C in persons with and without HIV co-infection is peginterferon-alpha-2a or 2b plus ribavirin (Box 55-1).1,3,4 Two distinct benefits have been attributed to HCV treatment. First, it is possible to eradicate the infection, referred to as a sustained virologic response (undetectable HCV RNA at the end of treatment and 6 months later). Marcellin and colleagues reported that 96% of patients with no detectable HCV RNA 6 months after therapy maintained their virologic response and experienced sustained histologic improvement during long-term follow-up.93 Similarly, Lau and co-workers reported that five patients with 6-month post-treatment virologic responses also had favorable clinical and histologic outcomes 6–13 years after therapy, with no detectable HCV RNA in the serum and liver tissue.94

BOX 55-1 HCV Treatment Algorithm in HIV-Infected Persons131

Modified from 2007 Guidelines for Management of HIV Related Opportunistic Infections, www.aidsinfo.nih.gov

Assessment Before Starting Therapy

Recommended Regimens

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree