Hemorrhagic Fevers: Epidemiology, Pathophysiology, and Clinical Features

L. Gayani Tillekeratne

Jennifer Cohn

Hillary Dunlevy

HEMORRHAGIC FEVERS

Background

Hemorrhagic fevers (HF) refer to illnesses largely caused by several distinct classes of viruses. The syndrome is characterized by fevers, multisystem illness, vascular permeability, and coagulopathy, which results in hemorrhage that ranges from mild to life-threatening in severity.1

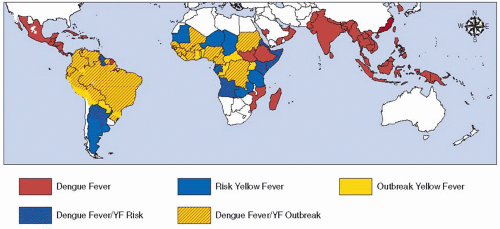

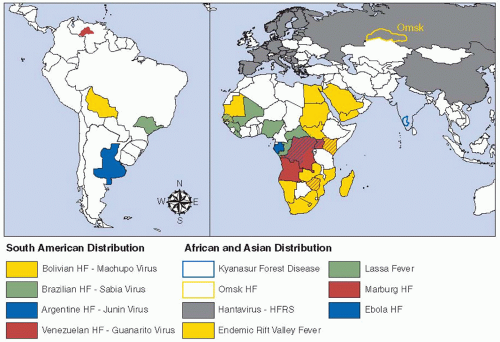

Four classes of viruses have been implicated in most cases of HF: the Arenaviruses, Filoviruses, Bunyaviruses, and Flaviviruses. These are all RNA viruses with a lipid envelope and are transmitted to humans either directly through animal hosts or through arthropod vectors.1 The epidemiology of disease in humans is thus largely determined by the geographical areas of the animal reservoir and vectors (FIGURES 124.1 and 124.2).2 Rodents and domesticated animals are the main reservoirs for viruses causing viral HF. Rarely, nonviral pathogens such as scrub typhus, caused by Rickettsia tsutsugamushi, can result in HF.1

Burden of Disease and Emerging Infections

Although there are accounts of HF-like syndromes since at least 1,545, the epidemiology of many HF is changing and new viruses are emerging.3 In 2009, heightened surveillance of acute febrile illness in China led to the identification of a novel Bunyavirus.4 The incidence of several HF has recently increased dramatically and spread to novel areas due to changes in global climate, the increased incidence of global travel, and the rise of urbanization.2 The past 50 years have seen a 30-fold increase in cases of dengue virus, and there has been a sharp increase in both the incidence of dengue fever and dengue hemorrhagic fever/dengue shock syndrome since 2000. This is largely attributed to the geographic expansion of the vector, Aedes aegypti mosquitoes, leading to increased co-circulation of all four serotypes of dengue.5 Expansion of the vector and increasing urbanization with crowded housing and poor sanitation have also increased the risk for yellow fever (YF) outbreaks.6

Scope of Clinical Illness

The symptoms of HF vary by type of pathogen and the immune system of the host. General initial symptoms include fever, headache, myalgia, and malaise. Patients with HF may exhibit signs of mild hemorrhage including petechiae and gingival bleeding or more severe hemorrhage including gastrointestinal bleeding. Considering the differential diagnosis in the initial presentation of HF is important, as it includes treatable illnesses, including malaria, typhoid, rickettsial, and other bacterial infections.

In general, the viral HF has a high case fatality rate. However, even with severe hemorrhage, patients do not usually die from blood loss. Death is often related to shock from a capillary leak syndrome and nervous system malfunction including coma and seizures.1 Laboratory findings often show thrombocytopenia, transaminitis, a coagulopathy, and/or evidence of disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC).

Travel history and incubation period of particular HF must be considered when evaluating a patient in the United States with a febrile multisystem illness and a bleeding diathesis. An infectious disease consultant and hospital infection control team should be immediately notified of any suspected case of HF.

Diagnosis and Treatment

Given that many of these diseases occur in resource poor settings, diagnosis is often clinical. General lab tests may reveal leukopenia with predominant lymphopenia, thrombocytopenia, and elevated transaminase. During the early viremic period of the illness, PCR may be useful in detecting the virus.7 Paired acute and convalescent serology is also used.8, 9 Treatment is generally supportive, and those with hemorrhagic complication deserve ICU level care.10 For those without clinically significant bleeding, replacement of blood products (particularly platelets) and clotting factors is not indicated but should be pursued in those with significant bleeding complications. Ribavirin has been shown to have benefit in human or animal models, the Arenaviridae and Bunyaviridae.11 Treatment with hyperimmune plasma has been shown to have some benefit in Argentinean and Bolivian HF in case studies but needs further study.12

Pathogenesis

The exact pathogenesis is incompletely understood. Initial local replication of virus in dendritic cells and macrophages progresses to viremia and widespread viral replication, which causes an intense cytokine response.13, 14 Cells, particularly macrophages, infected early in the course of disease produce an inflammatory response that is characterized by a variety of cytokines including IL-6, IL-8, reactive oxygen species, and nitrogen oxide. These cytokines may trigger immunosuppression by inducing lymphopenia through promotion of apoptosis as well as hypotension through increased vascular permeability and vasodilation.15, 16 In addition to vascular permeability and vasodilation, infection of and damage to the adrenal glands promote relative adrenal insufficiency and shock. Although

cytokines may trigger widespread tissue damage, particularly of the liver, infection and direct injury to endothelial cells seem to be a late event in the disease.17

cytokines may trigger widespread tissue damage, particularly of the liver, infection and direct injury to endothelial cells seem to be a late event in the disease.17

Several different mechanisms lead to hemorrhage including coagulopathy, vascular injury, vasodilation, and permeability of blood vessels.18, 19 Bleeding is frequently mucosal and includes gastrointestinal bleeding. Cytokines, in particular IL-6, are associated with coagulopathy that may be partially driven by increased expression of tissue factor.12 Rapid decrease in protein C has also been noted in Argentine hemorrhagic fever. Additionally, most HF can cause liver damage through direct viral mechanisms or through cytokine-induced injury, with resulting alteration in coagulation factors. Thrombocytopenia and deranged platelet function may be related to maturation arrest of megakaryocytes.12 DIC is most commonly noted in Rift Valley fever (RVF) and the Filoviruses but may be seen in late stages of any of the HF and represents a poor prognostic factor.20

Important Hemorrhagic Fever Viruses

Flaviviridae

The genus Flavivirus contains two of the most prevalent HF: YF and dengue. Omsk hemorrhagic fever virus and Kyasanur Forest virus can also cause severe disease in their endemic regions (Table 124.1).

Yellow Fever Virus

YF occurs in tropical and subtropical areas of Central and South America as well as sub-Saharan Africa, with the vast majority of cases occurring in Africa (see FIGURE 124.1).21 YF is characterized by sporadic outbreaks, and annual incidence may vary from a few thousand to hundreds of thousands of cases each year. Mosquitoes transmit the virus either from an infected monkey or another human.

Table 124.1 Other hemorrhagic fever viruses of importance | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree