CHAPTER 30 Helicobacter Pylori

Helicobacter Pylori at a Glance

The 2005 Nobel Prize for medicine was given to Robin Warren and Barry Marshall for their isolation, identification, and recognition of the pathophysiologic consequences of a bacterium that is able to chronically infect gastric mucosa. Beginning in 1983, these investigators reported the unexpected observation that the Helicobacter pylori bacterium is a principal cause of gastric and duodenal ulcers.1 Subsequently, H. pylori gastric infection has also been convincingly implicated as a risk factor for acute and chronic gastritis, dyspepsia, gastric carcinoma, and a form of gastric lymphoma known as ‘mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue’ (MALT) B-cell lymphoma. Since colonization and/or infection with H. pylori are particularly common in immigrant populations, it is important for physicians involved in the care of immigrant patients to be knowledgeable about the organism. In this chapter, we will first discuss the disease states associated with H. pylori and management considerations for patients in general. Then we will discuss special management considerations for immigrant populations.

Bacteriology

A spiral-shaped, Gram-negative, motile bacillus with multiple flagella, H. pylori is able to survive and thrive in the harsh acidic environment of the stomach (Fig. 30.1). H. pylori produces a protective urease enzyme that is able to convert urea to ammonia. The ammonia produced then serves as a buffering base to protect the organism from high gastric acidity. The organism is difficult to culture, but it can be demonstrated by histologic staining or by detection of its urease activity. Once the organism establishes itself in an individual’s gastric mucosa, it typically persists and becomes a long-term colonization or chronic infection. H. pylori elicits an inflammatory and immune response, with antibody production, but the organism is generally not eliminated from the host by this response. Chronic infection then ensues, typically with chronic gastritis. Initial gastric mucosal infection and persistence of infection are enabled by the bacteria’s motility, its production of urease, and its production of a variety of virulence proteins such as VacA and CagA (reviewed in reference 2).

Epidemiology

More than half of the world’s population is colonized with H. pylori! (This may beg the question; ‘What is “normal:” to be colonized or to be free of the organism?’) As shown in Table 30.1, the prevalence of ‘infection’ is 70–90% in less developed areas such as Asia, Africa, South and Central America, and Eastern Europe. Prevalence is much lower (though still in the range of 20%) in developed countries of Western Europe, North America, and Australia. It appears that the incidence in developed countries has decreased substantially since World War II, probably as a result of better sanitation and safe water supplies.

Table 30.1 Worldwide H. pylori prevalence and gastric cancer deaths

| Country/region | H. pylori prevalence (%) | Gastric cancer mortality (deaths/100 000/yr) |

|---|---|---|

| Americas | ||

| USA/Canada | 20–40 | <10 |

| Mexico | 70 | 10–20 |

| Andean So. Am. | 80–90 | >30 |

| So. Am. (other) | 80–90 | 10–20 |

| Europe | ||

| Western | 10–50 | 10–20 |

| Eastern | 70 | 20–30 |

| Russia | 70–80 | >30 |

| China/East Asia | 60–80 | 20–30 |

| India/SE Asia | 70 | 10–20 |

| Japan | 50 | >30 |

| Africa | 80–90 | <10* |

| Australia | 20–30 | 10 |

Data derived from reference 27 and the Helicobacter Foundation website at www.helico.com

Pathogenesis and Symptoms

It is important to recognize that, while a majority of the world’s population is infected (or colonized) with H. pylori, the vast majority of these infected persons will have no significant symptoms or medical consequences of the infection! Nevertheless, H. pylori infection is associated with several serious potential diseases. Why some individuals develop disease, while most do not, is unclear. However, proteins produced by various H. pylori subspecies, and not by others (such as VacA and CagA) may be important virulence factors that may favor the development of mucosal ulceration or cancer. Additional environmental or genetic cofactors, as yet unrecognized, may also be involved. The following conditions have been associated with gastric H. pylori infection.

Peptic ulcer disease (duodenal ulcer/gastric ulcer)

In the US, it has been estimated that peptic ulcers may occur in 10–20% of H. pylori-infected individuals, or a risk of 1% per year.3 Other estimates suggest a lifetime risk for ulcers of 3% for infected persons in the US, up to 25% for infected persons in Japan.2 Barry Marshall, in his Helicobacter pylori Foundation website, gives a figure of 30% lifetime risk for ulcer in infected persons. Thus, risk estimates for duodenal and gastric ulcer range from 3–30%. However, in some other countries where H. pylori prevalence is very high (such as Africa), reported ulcer incidence appears to be lower than would be expected from H. pylori infection prevalence data. This seeming contradiction may be explained by differing production of bacterial virulence proteins (including VacA and CagA) in regional H. pylori subspecies, by under-recognition/under-reporting of ulcers, or by additional environmental and ethnic factors involved in ulcer genesis.

The possibility of interactions between H. pylori and NSAIDs with respect to ulcer risk and complications is somewhat controversial. However, it is clear that both NSAIDs and H. pylori are independent risk factors for gastric and duodenal ulcers. Up to 20–30% of chronic NSAID users develop ulcer disease, and 1–1.5% of chronic NSAID users have bleeding per year. NSAID use is associated with 10 000–20 000 deaths from ulcer bleeding per year in the US.4 Risk for NSAID ulcer complications is increased for individuals older than 60 years, individuals with prior history of ulcer or ulcer complications, persons taking high-dose or multiple types of NSAIDs (such as NSAID plus cardioprotective aspirin), and persons concurrently taking prednisone or anticoagulants.4 Because of these added risks, it has been suggested that testing and treating H. pylori may reduce the chance for bleeding ulcer in such higher-risk persons who receive high-dose or long-term NSAIDs.5,6

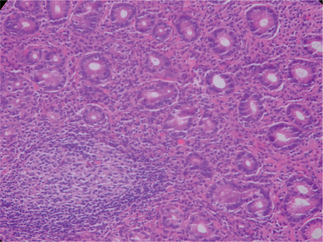

Gastritis

Initial infection with H. pylori appears to produce an acute neutrophilic gastritis with hypochlorhydria. Patients may have no symptoms, or they may experience acute dyspepsia – as described by Barry Marshall when he induced infection in himself.7 Typically, chronic infection or colonization of the gastric antrum (and to a lesser extent the gastric body and ectopic gastric mucosa in the duodenal bulb) ensues. Chronic infection is associated with the histologic appearance of chronic gastritis (Fig. 30.2). Mucosal gastritis may be appreciated visually during upper GI endoscopy, or the gastric mucosa may appear visually normal. Some subjects will develop more severe chronic gastritis that can progress to histologic atrophic gastritis and intestinal metaplasia. Intestinal metaplasia appears to be the histologic risk factor for development of distal gastric adenocarcinoma. Treatment of H. pylori may be able to cause regression8 or, at least, a reduced rate of progression of the histologic sequence.9 Patients with chronic gastritis from H. pylori also have subnormal acid production, and gastric acid production may actually increase after H. pylori infection has been eradicated.

Dyspepsia

‘Dyspepsia’ is an imprecise term that has been used to refer to a vague, but extremely common, constellation of abdominal and digestive symptoms. Complaints of pain, burning, gas, bloating, fullness after eating, nausea/vomiting, heartburn, etc. all may fall under this heading. Dyspepsia has been classified into three main categories: pain (‘ulcer-type’) symptoms, motility-type symptoms (such as postprandial fullness, nausea, and bloating), and reflux-type symptoms. While H. pylori has been associated with dyspeptic symptoms and eradication of the organism has been reported to relieve some symptoms in some patients, most dyspeptic patients – with or without H. pylori infection – do not appear to benefit from H. pylori treatment. This is probably related to the broad range of potential physical and psychological causes, including irritable bowel syndrome, which may create ‘dyspepsia’ symptoms. Initial enthusiasm for a generalized H. pylori ‘test and treat’ algorithm for dyspeptic patients has diminished. A review by Moayyedi et al. is illustrative: they report that 36% of chronic dyspeptics improved naturally, 57% continued to have chronic symptoms, and only 7–9% improved as a consequence of an H. pylori test-and-treat strategy.2,10,11

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree