Introduction

The International Headache Society (IHS) classification, ICHD-II,1 divides headaches into two broad categories: primary and secondary headache disorders. Secondary headaches are attributed to another disease and can be caused by intracranial or extracranial structural abnormalities or by systemic or metabolic conditions. In the primary headache disorders, the headache itself is the illness (Table 55.1). The primary headache disorders include migraine, tension-type headache (TTH) and trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias (including cluster headache). Migraine is further subdivided into two groups: migraine with and without aura. TTH is subclassified as either episodic tension-type headache (ETTH) or chronic tension-type headache (CTTH). Cluster headache is similarly divided into the episodic and chronic varieties. Chronic daily headache (CDH), a term in common use, is subclassified into CTTH, chronic migraine (CM), hemicrania continua (HC) and new daily persistent headache (NDPH), and is often associated with acute medication overuse.

Table 55.1 IHS migraine classification.

1. Migraine 1.1 Migraine without aura 1.2 Migraine with aura 1.2.1 Typical aura with migraine headache 1.2.2 Typical aura with non-migraine headache 1.2.3 Typical aura without headache 1.2.4 Familial hemiplegic migraine (FHM) 1.2.5 Sporadic hemiplegic migraine 1.2.6 Basilar-type migraine 1.3 Childhood periodic syndromes that are commonly precursors of migraine 1.3.1 Cyclical vomiting 1.3.2 Abdominal migraine 1.3.3 Benign paroxysmal vertigo of childhood 1.4 Retinal migraine 1.5 Complications of migraine 1.5.1 Chronic migraine 1.5.2 Status migrainosus 1.5.3 Persistent aura without infarction 1.5.4 Migrainous infarction 1.5.5 Migraine-triggered seizures 1.6 Probable migraine 1.6.1 Probable migraine without aura 1.6.2 Probable migraine with aura 1.6.5 Probable chronic migraine |

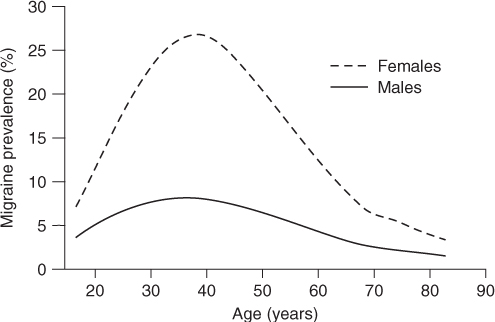

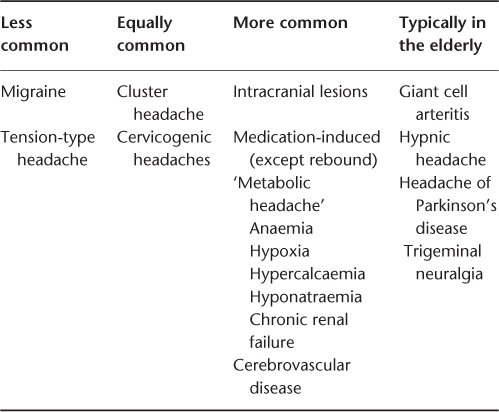

Headache prevalence is age dependent. Migraine prevalence peaks near age 40 years and declines afterward (Figure 55.1). With ageing, not only is there a change in prevalence of the primary headache disorder but also a shift to new or organic causes of headache.2 Migraine incidence and prevalence decrease, whereas brain tumours, subdural haematomas and other structural causes of headache increase. Elderly patients have more comorbid medical illness and some headache disorders, such as giant cell arteritis (GCA), occur principally in the elderly (Table 55.2).

Figure 55.1 Migraine prevalence by age. Prevalence increased from 12 to 38 years of age in both women and men; the peak was considerably higher among women. Reprinted from S.D. Silberstein and R.B. Lipton, Headache epidemiology: emphasis on migraine. Neurologic Clinics, 1996;14:421–34, Copyright 1996, with permission from Elsevier.

Table 55.2 Headache in the elderly.

Headache is common in the elderly. The 1 year prevalence of headache in an elderly Italian population (aged 55–94 years) was 40.5%; TTH 45.8%, migraine headache 5.7% and trigeminal neuralgia 1.6% In this population, headaches caused significant impairment of health-related quality of life.3 The complaint of ‘frequent headache’ was found in 11% of elderly women and 5% of elderly men participating in a health screening programme; however, these patients were commonly found to have other diseases or somatic or psychological symptoms.2 These facts justify a lowered threshold for ordering tests when older patients present with headache, particularly if the headaches are of recent onset, are atypical or are associated with neurological findings. Headaches that begin after age 65 years are more often secondary.

The evaluation of the elderly patient with headache must be directed to rule out serious secondary causes of headache such as tumour, subdural haematoma, stroke, transient ischaemic attack and giant cell arteritis. In the elderly patient, when the diagnosis is not obvious, neuroimaging and a sedimentation rate should be considered2 (Table 55.3). In this chapter, we discuss the primary headache disorders as they relate to the older patient, some of the more important secondary headache disorders and finally cranial neuralgias.

Table 55.3 Worrisome headache flags (SNOOP).

| System symptoms (fever, weight loss) or |

| Secondary risk factors (HIV, systemic cancer) |

| Neurological symptoms or abnormal signs (confusion, impaired alertness or consciousness) |

| Onset—sudden, abrupt or split-second |

| Older—new onset and progressive headache, especially in middle-age >50 years (giant cell arteritis) |

| Previous headache history—first headache or different (change in attack frequency, severity or clinical features) |

Source: American Headache Society and American Academy of Neurology. Neurology Ambassador Program for Continuing Medical Education, 2001; GlaxoSmithKline Grant.

Diagnosis and Clinical Description of Headaches

The criteria for headache diagnosis were updated by the IHS in 2004.1 The first step in establishing a diagnosis is a complete history, which should include the following information: the age at headache onset; the time of onset (day, season); the location, severity and type of pain; the attack frequency (including any change in frequency); associated symptoms; precipitating and relieving factors; the patient’s sleep habits; and the family history. In addition, a complete medication history should be taken to evaluate the doses, duration of use and effectiveness of previous headache medications, and also to determine if any medications that could exacerbate headaches are being used or overused.

The patient should keep a diary to record any changes in headache between office visits, especially if medication was modified. A diary will make the patient more aware of the disease process and also help the physician to evaluate the effectiveness and adverse effects of treatment. Patients should bring their medications with them periodically to check for compliance and to see if other physicians have prescribed any additional medications.

Primary Headaches in the Elderly

Migraine

Migraine occurs in 18% of women, 6% of men and 4% of children in the USA;4 62% of migraineurs also have TTH. Migraine usually begins in the first three decades of life and prevalence peaks in the fifth decade. The prognosis for migraine sufferers is good, since migraine prevalence decreases with increasing age. Although migraine can begin after age 50 years, a secondary organic cause must be considered when this occurs. In one study, only one of 193 patients with headache beginning after age 65 years had migraine. Cull5 collected 10 patients with migraine onset after age 60 years, two of whom had strokes on computed tomography (CT) finding. The ratio of migraine with aura to migraine without aura was reversed (86%:14%) among new onset migraine patients older than age 40 years. Whether this is due to referral patterns or biological factors is uncertain.

Migraine prevalence decreases with menopause, although the prevalence does not fall to premenarchal levels. The frequency of migraine aura without headache (migraine equivalents) in the elderly is unknown. In community-based studies, migraine prevalence varied from 0.3% in China (age >70 years) to 12% in Boston (age >65 years). In some, but not all, studies migraine prevalence continued to decrease in the very elderly.4

Clinical Features of Migraine

Migraine is an episodic headache disorder whose diagnosis depends on the characteristics of the pain and associated features. The ICHD-II criteria for migraine without aura (Table 55.4) require the patient to have at least five headache attacks.1 With time, the associated symptoms of migraine decrease, in part accounting for the decrease in migraine prevalence, since the headaches may no longer meet ICHD-II migraine criteria. The migraine aura may occur without the headache and migraine may remit or become transformed into CM (with or without medication overuse).

Table 55.4 Migraine without aura.

| Diagnostic criteria A. At least 5 attacks fulfilling criteria B–D B. Headache attacks lasting 4–72 h (untreated or unsuccessfully treated) C. Headache has at least two of the following characteristics: 1. Unilateral location 2. Pulsating quality 3. Moderate or severe pain intensity 4. Aggravation by or causing avoidance of routine physical activity (e.g. walking or climbing stairs) D. During headache at least one of the following: 1. Nausea and/or vomiting 2. Photophobia and phonophobia E. Not attributed to another disorder |

A diagnosis of migraine with aura (classic migraine) requires the patient to have at least two attacks with at least three of the characteristics listed in Table 55.5. If the aura lasts longer than 1 h but less than 1 week, the condition is called migraine with prolonged aura.1 Migraine is more than just an aura and a headache. Some patients have four phases: the premonitory phase, the aura, the headache and the postdrome. About 60% of patients have a prodrome, which occurs hours to days before the headache. During this time, patients may have various psychological, sensory, constitutional or autonomic symptoms. Not all patients experience a prodrome, but if they do, their prodromal symptoms are usually the same each time. The symptoms can continue into the aura and headache phases.6 The aura develops over 5–20 min, lasts from 20 to 30 min and consists of focal neurological symptoms that accompany the headache or occur up to 1 h before it begins. About 20% of migraineurs experience an aura, which may be visual, sensory or motor or involve speech disturbances. Visual symptoms are the most common and include scintillations (fluorescent flashes of light in the visual field), fortification spectra or teichopsia (alternating light and dark lines in the visual field), photopsia (flashing lights) and positive (bright geometric lights in the visual field) and negative (blind spots that may move across the visual field) scotomata. Sensory symptoms include numbness, tingling or paraesthesias of the face or hand.

Table 55.5 Migraine with aura.

| Diagnostic criteria |

A. At least 2 attacks fulfilling criterion B B. Migraine aura fulfilling criteria B and C for one of the subforms 1.2.1–1.2.6 C. Not attributed to another disorder |

| 1.2.1 Typical aura with migraine headache |

| Diagnostic criteria A. At least 2 attacks fulfilling criteria B–D B. Aura consisting of at least one of the following, but no motor weakness 1. Fully reversible visual symptoms including positive features (e.g. flickering lights, spots or lines) and/or negative features (i.e. loss of vision) 2. Fully reversible sensory symptoms including positive features (i.e. pins and needles) and/or negative features (i.e. numbness) 3. Fully reversible dysphasic speech disturbance C. At least two of the following: 1. Homonymous visual symptoms and/or unilateral sensory symptoms 2. At least one aura symptom develops gradually over ≥5 min and/or different aura symptoms occur in succession over ≥5 min 3. Each symptom lasts ≥5 and ≤60 min D. Headache fulfilling criteria B–D for 1.1 Migraine without aura begins during the aura or follows aura within 60 min E. Not attributed to another disorder |

Motor symptoms are usually hemiparetic, while language disturbances consist of difficulty in speaking (aphasia) or understanding.6 The headache can begin at any time during the day. The pain usually develops gradually and then subsides after 4–72 h. A headache lasting longer than 72 h defines status migrainosus. The pain is usually located in the temples, but it can occur anywhere in the face or head and may radiate down the neck and shoulder. The pain is moderate to severe in intensity and usually described as throbbing or pulsating. Pain is usually unilateral, but may begin as or become bilateral. Strictly unilateral headaches are not of concern since they occur in 20% of migraineurs. Accompanying symptoms are common: most patients are anorectic and have nausea; some vomit or have diarrhoea. Photophobia and phonophobia cause patients to seek relief in a dark, quiet room to decrease sensory stimulation. Most patients have 1–4 attacks per month. After the headache phase, some patients experience a postdrome or recovery phase that may last up to 24 h. Some patients feel tired, others feel alert, some feel depressed, others feel euphoric, some feel worn out, and some feel refreshed. Some may complain of poor concentration, food intolerance or scalp tenderness. Medications that are more commonly used by the elderly may exacerbate or trigger migraine. Analgesic, ergotamine or triptan overuse can cause CDH in patients of all ages. Nitroglycerine and other nitrates may exacerbate migraine. Estrogen replacement therapy may either exacerbate or ameliorate migraine. Reserpine, an antihypertensive agent, is a recognized migraine trigger.

Migraine Equivalents of the Elderly

In the elderly, migraine aura without headache (acephalic migraine) is also called late-life migraine accompaniments. It may occur for the first time in a patient over the age of 40 years.7 Its diagnosis is particularly treacherous in patients with no prior history of migraine and should be made by exclusion unless the symptoms are pathognomonic of the migraine aura (e.g. scintillating scotomata lasting 30 min). Features are listed in Table 55.6. The headaches are usually absent or mild, if present at all, and neuroimaging is normal. The IHS diagnostic criteria are the same as in Table 55.5, migraine with aura, except for no headache.1 Cerebrovascular disease (cerebral embolism or thrombosis, carotid or vertebral dissection, subclavian steal syndrome), epilepsy, polycythaemia, lupus anticoagulant, hyperviscosity syndrome and psychiatric spells must always be considered in the differential diagnosis and must be ruled out by the appropriate studies.2 A syndrome of recurrent somatosensory aura, sometimes followed by a headache and associated with small cortical subarachnoid haemorrhage, has recently been described; 3–7 episodes occurred over 2 days to 5 months.8

Table 55.6 Migraine equivalents.

1. Gradual appearance of focal neurological symptoms’ spread or intensification over a period of minutes 2. Positive visual symptoms characteristic of ‘classic’ migraine, specifically fortification spectra (scintillating scotoma), flashing lights, dazzles 3. Previous similar symptoms associated with a more severe headache 4. Serial progression from one accompaniment to another 5. The occurrence of two or more identical spells 6. A duration of 15–25 min 7. Occurrence of a ‘flurry’ of accompaniments 8. A generally benign course without permanent sequelae |

Treatment of Migraine Headache in the Elderly

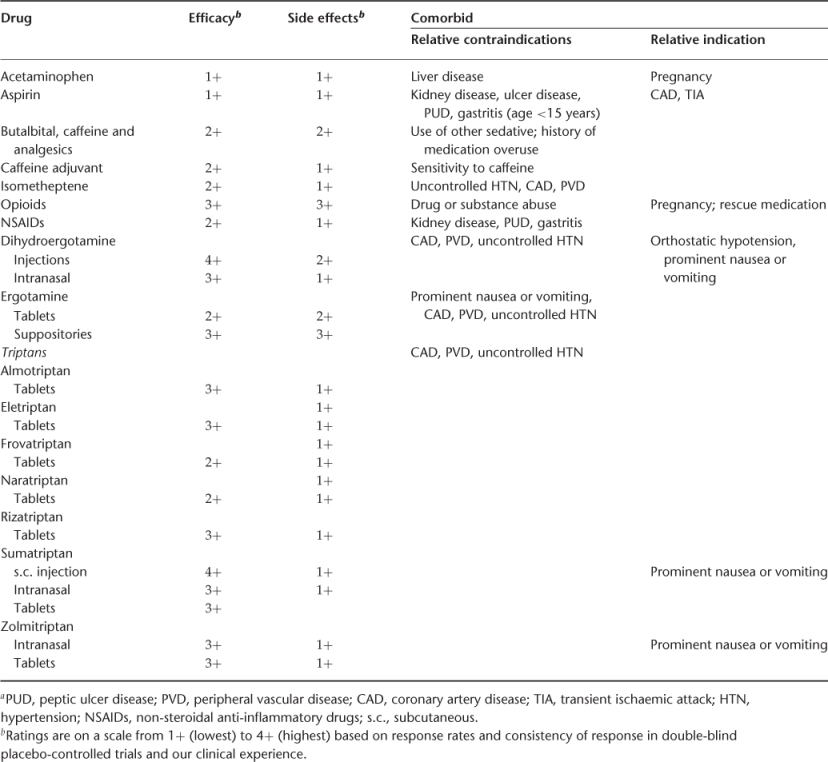

Headache treatment begins with making the diagnosis and explaining it to the patient, since all treatment depends on establishing a therapeutic relationship. Drug treatment may be acute, preventive or both, supplemented by nonpharmacological treatment (Table 55.7). Acute migraine treatments are listed in Table 55.8. Because of an increased risk of cardiovascular disease, ergot alkaloids, triptans and other vasoconstrictors, such as isometheptane mucate (present in Midrin), must be used with caution, if at all, in the elderly. Benzodiazepines and barbiturates may cause excessive sedation; the long-acting benzodiazepines, in particular, may cause excessive side effects due to slowed metabolic clearance. Antiemetic drugs and neuroleptics are more likely to cause tardive dyskinesia in the elderly. Even non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) may cause cognitive side effects and are associated with an increased risk of gastrointestinal bleeding 9.

Table 55.7 Migraine treatment.

| Acute (symptomatic) |

| Specific—for migraine only |

| Non-specific—for any pain disorder or associated symptoms |

| Preventive (prophylactic) |

| Pre-emptive—immediately prior to triggering event |

| Short-term—for a limited time |

| Chronic—continuous |

Table 55.8 Acute medications: efficacy, side effects, relative contraindications and indicationsa.

Preventive treatments (Table 55.9) may also cause more side effects and be less well tolerated in the elderly. Therefore, they should be started at a very low dose and increased slowly. The tertiary amine tricyclic antidepressant agents, such as amitriptyline and doxepin, which are potent anticholinergic agents, should be used with caution. They can exacerbate glaucoma, produce visual blurring and cause problems with cognition. Nortriptyline, a secondary amine, is a reasonable alternative and generally has less pronounced side effects. The selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, although not as effective, are very safe in the elderly. Antihypertensive drugs may cause more hypotension or lethargy in the elderly than in younger patients. Divalproex sodium and topiramate have a particularly good benefit-to-side effect profile in the elderly. Methysergide (no longer available in the USA) and methylergonovine are relatively contraindicated because they are vasoconstrictors and may cause cardiac ischaemia.9

Table 55.9 Prevention.

| Drug | Efficacya | Side effectsa |

| Beta-blockers | 4+ | 2+ |

| Neurotoxins | ||

| Onabotulinumtoxin A (CM) | 3+ | 1+ |

| Calcium channel blockers | ||

| Verapamil | 2+ |