Major Concepts

Diseases and Symptoms

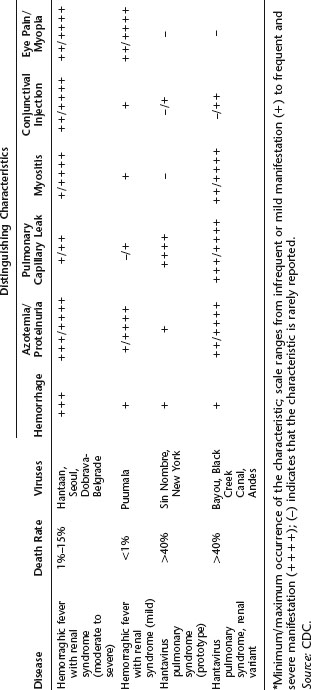

Hantaviruses cause two major types of disease in humans: hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome (HFRS) and hantavirus pulmonary syndrome (HPS). Severe cases of HFRS result from infection with the Hantaan virus in Asia and Europe or the Dobrava virus in the Balkans. HFRS is characterized by the abrupt onset of high fever, severe abdominal or lower back pain, hemorrhagic symptoms, and renal dysfunction that severely diminishes the ability of the kidneys to produce urine. Fluid accumulates in the lungs, particularly if large volumes of water are consumed. The hemorrhagic manifestations include petechiae, severe hemorrhaging, and disseminated intravascular coagulation. The mortality rate is 5% to 15%, and between 40,000 and 100,000 persons are afflicted annually. HPS is caused by the Sin Nombre virus in North America and the Andes and the Laguna Negra, HU39694, Lechiguanas, Oran, and Juquitiba viruses in South America. Kidney involvement is limited, and hemorrhagic symptoms are uncommon. The early symptoms of this disease are fever, chills, fatigue, myalgia, headache, malaise, and dizziness, accompanied by gastrointestinal symptoms. The cardiorespiratory phase follows with leakage of high-protein-content fluid into the alveoli of the lungs and hypoxia, tachypnea, tachycardia, and mild hypotension. Later, respiratory symptoms such as coughing and shortness of breath develop in all patients. In many cases, death occurs rapidly after fluid enters the lungs and may be attributable to hypoxia or circulatory collapse due to low cardiac output and high systemic vascular resistance, hypotension, or shock. Overall mortality rate ranges from 20% to 40%.

Infection

Hantaviruses are spheroid to oval, enveloped negative-sense single-stranded RNA viruses of the Bunyaviridae family. They infect primarily endothelial cells. Other hantaviruses causing less severe HFRS-like pathology in humans are the Seoul virus (worldwide), the Puumala virus (Scandinavia), and the Bayou, Black Creek Canal, Monongahela, and New York viruses (North America). Hantaviruses are transmitted through dried, aerosolized excreta of rodents: Sin Nombre virus uses the deer mouse as its vector. A major outbreak of HPS occurred in 1993 due to increased deer mouse populations resulting from more plentiful food sources and mild weather produced by El Niño climatic conditions.

Immune Response

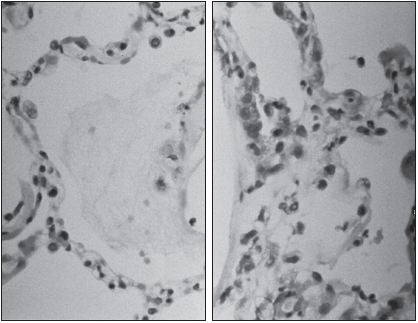

The immune system’s response to hantavirus infection is often pathogenic. Atypical T lymphocytes induce capillary leakage during HPS. CD4+ Th1 T helper cells secrete interferon-γ, activating macrophages that are present in high numbers in the alveoli of the lungs. These cells produce additional cytokines, stimulating inflammatory responses that accentuate lung pathology. IFN-α and IFN-β, by contrast, appear to play protective roles in HFRS. Differences occur in the immune responses to nonpathogenic versus pathogenic hantaviruses. The former induce expression of a number of interferon-stimulated genes that are not activated by the latter. The Hantaan virus, for its part, stimulates expression of some genes involved in the pathology of HFRS, including hematopoietic growth factors, chemokines, cell adhesion molecules, and the complement system.

Treatment and Prevention

Treatment for HPS is supportive and requires hospitalization to maintain fluid balance and blood oxygenation levels and to avoid hypoxia and shock. Preventive measures may be taken to decrease contact with infectious rodent excreta. Infrequently inhabited cabins or vacation homes should be carefully cleaned to avoid inhaling dried urine, feces, or saliva. Areas such as floors, walls, and shelving that contain rodent droppings should be sprayed or liberally wetted with disinfectants to kill viruses prior to sweeping or dusting. Gloves and a respiratory mask should be worn during this process. Persons working with rodents need to take special precautions during contact with rodents or their excretions.

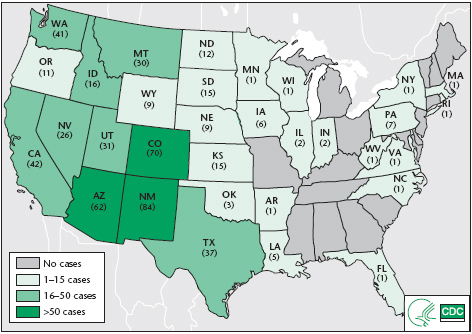

In the early 1990s, a highly pathogenic outbreak of respiratory illness began in portions of the southwestern United States. Its route of transmission was unknown, and it appeared to be caused by a novel infectious organism. This agent was soon discovered to be a close relative of the Hantaan virus, which causes a hemorrhagic disease with renal manifestations, primarily in Asia. By June 2002, a total of 318 cases of the new disease, designated as hantavirus pulmonary syndrome (HPS), were confirmed, with a mortality rate of 37%. By tracing Native American legends, however, it appears that periodic outbreaks of this disease have occurred for a much longer period of time and are related to changes in rodent populations in response to climatic conditions. Native Americans were affected at a disproportionately high rate: 22% of infected individuals belonged to that group, while 76% were white Americans. At least 31 U.S. states, parts of western Canada, and a number of countries in South America have reported cases of this respiratory syndrome. Infection in the eastern United States is uncommon, particularly in the American South. The largest numbers have occurred in Arizona, New Mexico, California, and Washington. HPS is rare or absent in Mexico, Central America, and the Caribbean, despite the presence of infected sigmodontine rodents in the continental areas. (Many of the native rodents in the Caribbean have been displaced by Old World rats and mice.)

Some segments of the population are at higher risk of acquiring HPS than others. Fully 75% of the cases were reported in rural locales with increased exposure to the rodent reservoirs and vectors. Males tend to have a higher rate of infection than females, perhaps due to their increased exposure to infectious material in cabins or through agricultural pursuits.

FIGURE 20.1 Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome (HPS) cases, by reporting states

Note: Cumulative case counts as of July 1, 2010. Total cases: 545 in 32 states.

Source: CDC.

Hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome was described by Soviets and Japanese in Manchuria near the Amur River; 12,000 Japanese troops stationed in the area were affected by this disease in the 1930s. Similar symptoms were described in a Chinese medical book written in A.D. 960. The disease was later noted in other areas of Asia as well in 1951 during the Korean War, when more than 3,200 United Nations troops came down with a hemorrhagic fever associated with greatly reduced urine production. This disease was found to be caused by infection with the Hantaan virus and is currently a major health threat in China and South Korea. Several other hantaviruses were later detected in various areas of the world, and some of these were associated with similar or differing illnesses.

Although several species of hantavirus were found in North America, these were not known to be pathogenic until 1993. At that time, an epidemic of adult respiratory distress syndrome began in the Navaho population of the American Southwest, particularly in the Four Corners area where the states of Colorado, Utah, New Mexico, and Arizona meet. The high numbers of Navahos in the initial outbreak led some observers to call this illness the “Navaho disease” and to avoid contact with Native Americans in that region. The affected persons were screened against a large panel of infectious agents and were eventually found to produce antibodies that were cross-reactive with the types of hantavirus occurring in Asia. The disease was subsequently named hantavirus pulmonary syndrome. The causative agent was initially dubbed the Muerto (Death) Canyon virus, but because it differed from previously identified hantaviruses, it was later designated the Sin Nombre (“without a name”) virus (SNV). An earlier confirmed case of HPS in the United States was later backdated to 1959 in Utah.

Prior to 1993, two species of hantavirus were recognized in the Americas. The Prospect Hill virus from meadow voles caused no human illness in the United States, and the Seoul virus of Old World rats rarely caused disease in humans in the Western Hemisphere. The Seoul virus is found throughout the country, as well as on other continents, and is associated with hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome in some locations.

Hantavirus infection leads to two distinct and serious illnesses. These diseases are caused by different species of virus and occur largely in different parts of the world, although some overlap exists in the ranges of the appropriate reservoir and viral species. The bulk of this chapter is devoted to hantavirus pulmonary syndrome and its vectors, which are found in the Americas.

Table 20.1 Distinguishing clinical characteristics for HFRS and HPS

Hemorrhagic Fever with Renal Syndrome (HFRS)

Individuals with hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome (HFRS), also known as Korean hemorrhagic fever, experience an abrupt onset of high fever, severe abdominal or lower back pain, hemorrhagic symptoms, and renal dysfunction. The kidneys have greatly diminished ability to produce urine. Fluid accumulates in the lungs, a condition that may be worsened if the person consumes large volumes of water to stimulate urination. As its name suggests, HFRS induces hemorrhagic manifestations, such as petechiae, severe hemorrhaging, and disseminated intravascular coagulation. Cellular damage occurs in the kidneys, the anterior pituitary gland, and the right atrium of the heart. Symptoms may include hypotension and shock, headache, nausea, and vomiting. Other laboratory findings include thrombocytopenia and increased serum creatinine and blood urea nitrogen levels. Although the majority of patients recover in weeks or months, others are more severely affected, and the mortality rate is 1% to 15%.

HFRS is caused primarily by two hantaviruses, the Hantaan and Dobrava viruses. Approximately 40,000 to 100,000 cases of HFRS due to the Hantaan virus are reported annually in Asia, with greater than half that number from China. Several hundred cases due to the Dobrava virus are also reported in the Balkans each year. The Seoul virus may also cause HFRS. It thrives in rats in major cities throughout the world but is regularly linked to disease only in Asia. A generally milder disease called nephropathia epidemica results from infection with another hantavirus, the Puumala virus. This form of the disease occurs in most European countries, including the Balkans and Russia west of the Ural Mountains.

Hantavirus Pulmonary Syndrome (HPS)

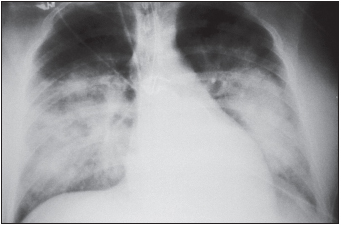

The early symptoms of HPS include fever, chills, fatigue, muscle aches, headache, malaise, and dizziness, which typically last four to six days. These may be accompanied by gastrointestinal symptoms, including nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain, but not by cough during the initial stages of infection. The later-occurring cardiorespiratory phase begins with the leakage of high-protein-content fluid into the alveoli (terminal air sacs) of the lungs, causing hypoxia (low blood oxygen levels), tachypnea (rapid breathing), tachycardia (rapid heart rate), and mild hypotension. Blood profiles include thrombocytopenia (low platelet levels) in almost all patients. Decreased platelet numbers generally inhibit the blood-clotting process, but hemorrhage is uncommon during HPS. These findings are often accompanied by hemoconcentration and an elevated hematocrit due to loss of fluid from the blood into the lungs and pleural cavity, resulting in pulmonary edema. Circulatory abnormalities include a “left shift”—the presence of immature white blood cells (myelocytes) in the circulation; circulating immunoblasts; hypoalbuminemia; and metabolic or lactic acidosis in the late stages of disease. Elevated levels of aspartate aminotransferase and lactate dehydrogenase are also frequently seen. Radiography of the chest is useful in diagnosis, and the disease progresses to frank bilateral alveolar edema (accumulation of fluid in the air sacs of the lungs). Late respiratory symptoms in all patients are coughing and shortness of breath. Unlike HFRS caused by a similar virus, HPS has a limited involvement of the kidneys, although proteinuria and abnormal urinary sediment are often found. The hemorrhagic manifestations of HFRS, such as overt bleeding or disseminated intravascular coagulation, are not common. The differential diagnosis needs to consider leptospirosis, rickettsial infection, American hemorrhagic fevers, and acute respiratory distress syndrome resulting from influenza A, mycoplasmosis, pneumonic plague, or pulmonary anthrax.

In many cases, progression to death occurs rapidly upon the entry of fluid into the lungs, often within 24 to 48 hours after hospital admission, and is generally attributable to hypoxia or circulatory collapse, commonly associated with low cardiac output and high systemic vascular resistance. Hypotension and shock may also occur. The mortality rate is high—in the 1993 outbreak, more than 50% of infected individuals died. The rate was 40% between 1994 and 1996 and 20% in 1997. Mild disease is not the normal outcome of SNV infection; most infections progress to HPS. Young children are exceptions to this generalization, small numbers of them being infected with milder courses of disease.

The viruses themselves are not directly destructive to infected cells; rather, the damage appears to result from actions of the immune system. The lungs are a major entry site for microbes and therefore contain a large number of T lymphocytes, particularly the CD8+ T killer cells that kill infected cells as well as uninfected cells in the vicinity. Pathogenesis is also due to the production of cytokines by CD4+ T helper cells, activating further injury by other leukocytes (discussed later in this chapter).

Hantaviruses belong to the family Bunyaviridae, of which at least 20 species occur in the Americas. These are enveloped negative-sense single-stranded RNA viruses containing three RNA segments, large, medium, and small. They encode a number of viral proteins, such as RNA-dependent RNA transcriptase (responsible for transcription of RNA), the envelope glycoproteins, and the nucleocapsid protein. These viruses are spheroid to oval with a diameter of 95 to 110 nanometers. They primarily infect endothelial cells, which line the vasculature. Pathogenic, but not nonpathogenic, hantaviruses utilize the αvβ3 integrin during entry into the cells. This integrin interacts with vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 (VEGFR-2). Alterations in vascular permeability occur in both HFRS and HPS.

Table 20.2 Pathogenic members of the genus Hantavirus, family Bunyaviridae

Source: CDC.

| Species | Disease | Virus Distribution |

| Hantaan | HFRS | China, Russia, Korea |

| Dobrava-Belgrade | HFRS |