Handling of Colorectal Cancer Resection Specimens

Rhonda K. Yantiss

Virtually all carcinomas of the colorectum develop from preexisting neoplasms, namely, adenomas, serrated polyps, and inflammatory bowel disease-related dysplasia. Improved endoscopic techniques and widely available colorectal cancer screening and surveillance programs enable clinicians to remove large, potentially malignant lesions with minimally invasive approaches. As a result, pathologists increasingly encounter invasive carcinomas in endoscopically obtained samples as well as colectomy specimens. Pathologists must perform several functions when assessing cancer specimens, namely, tumor staging, assessment of resection adequacy, and documentation of background disease, if present. Understanding the anatomy and features of colorectal cancer in resection specimens is necessary to accurately document extent of disease and judiciously submit an appropriate number of tissue blocks. The purpose of this chapter is to discuss the gross handling of colorectal cancer specimens.

ENDOSCOPICALLY OBTAINED POLYPECTOMY SPECIMENS

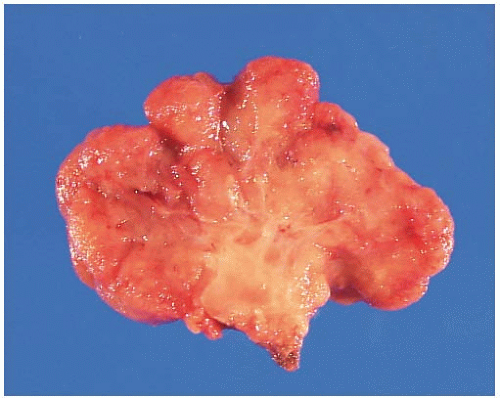

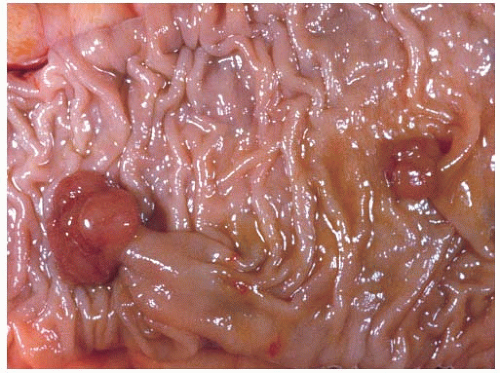

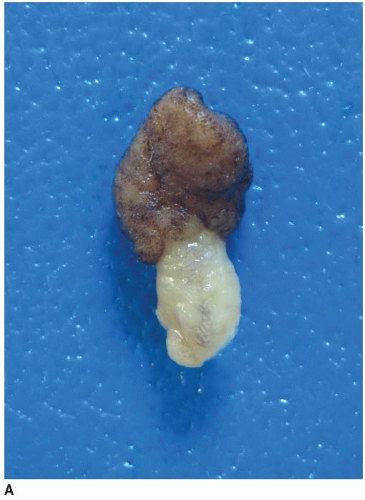

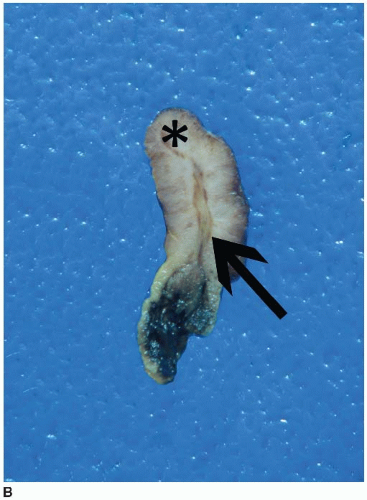

Colorectal polyps are classified as epithelial, mesenchymal, and mixed polyps based on their primary components. The nature of a polyp may be suspected at the time of gross examination. Epithelial polyps, such as adenomas, are mostly composed of a proliferation of epithelial cells and, thus, display expansion of the mucosa that is readily apparent on cross section (Figure 6.1). Most polyps composed of mesenchymal elements are derived from the muscularis mucosae or submucosa and appear as sessile nodules with a rounded, smooth surface (Figure 6.2). Mixed polyps, including mucosal prolapse polyps and hamartomas, may contain splayed bundles of smooth muscle cells emanating from the hyperplastic muscularis mucosae, which produce a thick, dense stalk (Figure 6.3).

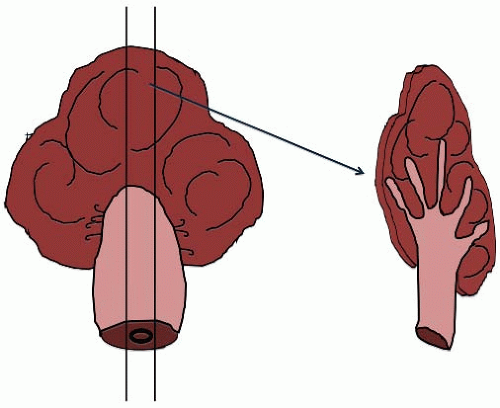

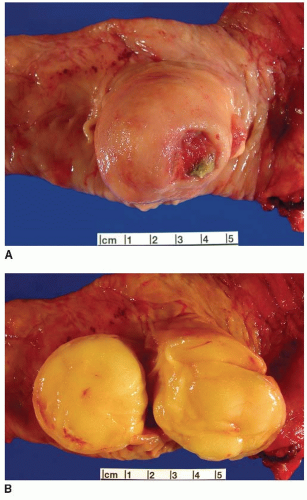

Colorectal adenomas are classified as pedunculated or sessile based on their endoscopic appearance. Pedunculated adenomas contain a stalk comprising normal mucosa and submucosa, presumably resulting from chronic trauma as the polyp is pulled in the direction of the fecal stream (Figure 6.4). Sessile polyps rest on the colonic mucosa without an apparent stalk (Figure 6.5). Pedunculated polyps typically display a tubular morphology, whereas sessile polyps are tubular, villous, or tubulovillous. Colorectal adenomas are entirely benign and cured by complete excision. Less than 5% harbor malignant foci, although approximately 20% of adenomas spanning more than 2 cm contain invasive adenocarcinoma. Other risk factors for cancer development in adenomas include the presence of high-grade dysplasia and/or a villous component that accounts for at least 25% of the polyp volume.1,2 Early invasive adenocarcinomas limited to the submucosa may be amenable to endoscopic excision, particularly if associated with a pedunculated adenoma, as discussed in Chapter 8.3

Gross Processing of Polypectomy Specimens

Pedunculated and sessile colorectal adenomas are amenable to snare polypectomy and endoscopic removal. Pedunculated polypectomy specimens often contain an identifiable base or stalk, the latter of which may appear slightly retracted. If the polyp base is identified, then a small

amount of ink should be placed at the resection margin. Sessile polyps can be removed by injecting the polyp base with a combination of norepinephrine and saline to lift the lesion off the submucosa, although larger lesions may require piecemeal resection. Injection of a flat polyp creates a fluid-filled wheal at the base that simulates the appearance of a stalk in histologic sections. Thus, the gross appearance of a polyp is best determined at the time of endoscopic evaluation. Large sessile polyps of the distal rectum may also be excised with an attached disc of mucosa and submucosa. The underside and lateral aspects of these mucosal resection specimens represent surgical margins, which are commonly inked, pinned out (deep margin side down), and fixed for a few hours prior to sectioning. Intact and fragmented polyps are sectioned at 2 mm intervals and submitted entirely for histologic evaluation (Figure 6.6).

amount of ink should be placed at the resection margin. Sessile polyps can be removed by injecting the polyp base with a combination of norepinephrine and saline to lift the lesion off the submucosa, although larger lesions may require piecemeal resection. Injection of a flat polyp creates a fluid-filled wheal at the base that simulates the appearance of a stalk in histologic sections. Thus, the gross appearance of a polyp is best determined at the time of endoscopic evaluation. Large sessile polyps of the distal rectum may also be excised with an attached disc of mucosa and submucosa. The underside and lateral aspects of these mucosal resection specimens represent surgical margins, which are commonly inked, pinned out (deep margin side down), and fixed for a few hours prior to sectioning. Intact and fragmented polyps are sectioned at 2 mm intervals and submitted entirely for histologic evaluation (Figure 6.6).

Gross Evaluation of Colectomy Specimens

Systematic pathologic evaluation of colorectal cancer resection specimens plays a vital role in determining the patient’s prognosis and facilitating decisions regarding use of adjuvant therapy. Awareness of the clinical history and nature of the surgical procedure ensures appropriate handling of the case. It is important to accurately document all components of a resection specimen, note the anatomic location of the tumor and its relationship to relevant surgical margins, and describe the presence, if any, of underlying conditions. Specific details about the tumor, including configuration (i.e., ulcerated, polypoid, fungating) and size, should be noted and documented with photography, if available. Although there are no universally

accepted guidelines regarding the appropriate number of sections obtained from colorectal cancer resection specimens, we advocate submission of at least four sections of the tumor, including a minimum of two sections documenting deepest invasion and one of the adjacent mucosa, all regional lymph nodes, margins as appropriate, any other findings (e.g., polyps, tattoo, inflammation), and sampling of other organs composing the specimen, such as the ileum or appendix.

accepted guidelines regarding the appropriate number of sections obtained from colorectal cancer resection specimens, we advocate submission of at least four sections of the tumor, including a minimum of two sections documenting deepest invasion and one of the adjacent mucosa, all regional lymph nodes, margins as appropriate, any other findings (e.g., polyps, tattoo, inflammation), and sampling of other organs composing the specimen, such as the ileum or appendix.

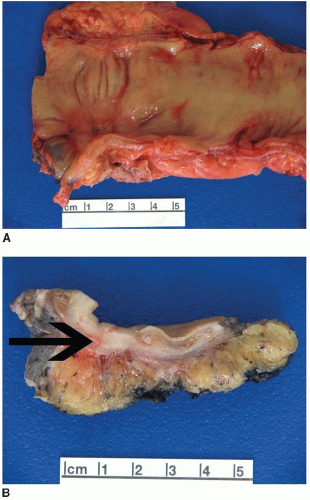

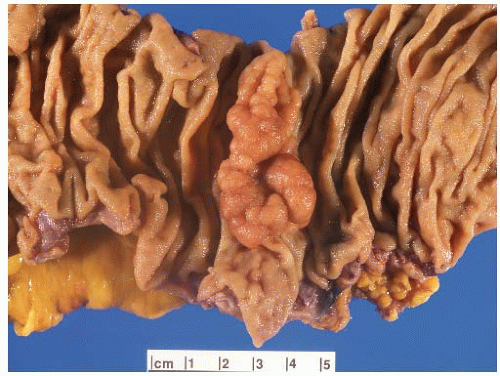

FIGURE 6.1: A large adenoma has a lobulated, slightly granular surface, reflecting expansion of its mucosa by neoplastic epithelium (A). |

FIGURE 6.1: (Continued) A cross section through the adenoma demonstrates a thickened mucosa (asterisk), which is demarcated from the underlying submucosa (arrow). The base of the polyp is inked (B). |

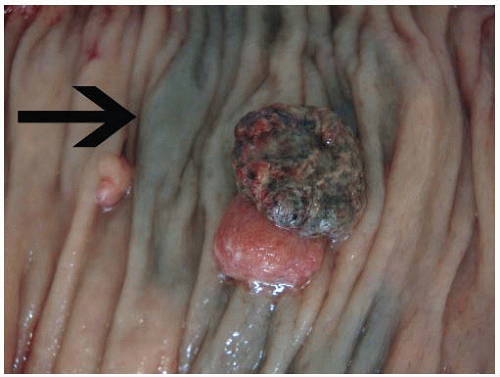

Pathologists evaluate colorectal tumors in order to assign tumor stage, assess resection adequacy, and document background disease, if present. Colorectal surgery is the mainstay of therapy for most types of neoplasia, in which case the resection specimen usually contains an adenoma, carcinoma, or other tumor type. Surgery can also follow endoscopic manipulation or neoadjuvant therapy, both of which alter the appearance of the lesion. Early invasive adenocarcinomas in large polyps may produce ulcers or surface irregularities that prompt gastroenterologists to tattoo the mucosa with India ink (Figure 6.7). In other situations, the diagnosis of invasive adenocarcinoma is only made following polypectomy, so subsequent resections are performed for lymph node staging and contain only a polypectomy site with, or without, an associated tattoo. Finally, locally advanced rectal adenocarcinomas and anal squamous cell carcinomas are routinely treated with neoadjuvant therapy that induces variable tumor regression prior to surgery. Treated cancers form ulcers in the distal rectum with scarring of the wall and pericolic fat that should be extensively sampled to document residual disease, as described in Chapters 8 and 9 (Figure 6.8).

FIGURE 6.2: A submucosal lipoma has a smooth round appearance except in the area of an ulcer (A). This polyp displays a fatty yellow cut surface (B). |

FIGURE 6.5: A sessile adenoma of the ascending colon forms a flat, irregular plaque on the mucosal surface. |

Inking and Evaluating Resection Margins

A number of problems arise when assessing surgical resection margins on colectomy specimens, although most issues are resolved following close examination of the specimen, review of the radiology report, and direct conversation with the surgeon. Common problems include inadvertent inclusion of the serosa as a resection margin and failure to recognize the radial resection margin. All colorectal resection specimens have at least three margins: the proximal and distal visceral margins of the tubular gut and one, or more, soft tissue (radial) margins. The ileum always comprises the proximal margin of right colonic resection specimens. Tubular gut resection margins of abdominal colon cancers are usually distant from the tumor. Those that are greater than 3 cm from the advancing tumor edge are sufficiently evaluated by gross examination alone since primary colorectal carcinomas do not show extensive lateral or submucosal tumor spread in most cases.4 Colonic resection margins located 1 to 3 cm from the tumor edge may be taken en face, but margins less than 1 cm from the tumor should be inked and sampled with perpendicular sections.

The radial margin is a soft tissue resection margin, and its nature varies depending on the anatomic location of the tumor and the type of surgical specimen obtained (Table 6.1). For example, the sigmoid colon lies within the peritoneal cavity and is supported by a mesentery transection of which represents the radial margin. The remaining pericolic fat on the sigmoid colon is surfaced by mesothelial cells (e.g., serosa) and does not constitute a surgical resection margin. Thus, a tumor that invades through the sigmoid colon wall and extends to the surface of peritonealized fat is assigned a pT4a pathologic stage with a negative margin, whereas a tumor extending to the mesenteric margin (usually designated with sutures at the vascular pedicle) is assigned a pT3 pathologic stage with a positive margin. Other parts of the colon that lie partially within the peritoneal cavity (i.e., ascending and descending colon) are surfaced anteriorly by peritoneum but lie on the posterior abdominal wall, which represents a margin. Tumors that occur in these areas have both mesenteric and posterior radial margins, although the latter are rarely of clinical significance. The serosa of the colon is not a surgical margin, although some pathologists may advocate inking it in order to document serosal penetration (pT4a) in some cases. Should one adopt this practice, a different color is used to denote the serosa in order to avoid potential confusion with the radial margin.

Table 6.1 Radial Margins on Colorectal Resection Specimens | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|