TRANSMISSION OF MICROORGANISMS AND HAND HYGIENE BEHAVIOR

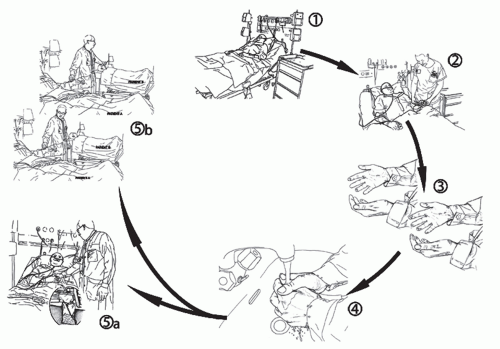

A clear understanding of the process of hand-pathogen transmission is critical to successful education strategies, assessment of HCWs’ hand hygiene performance, and research. An evidence-based model of hand transmission was proposed by Pittet et al. and served as a basis for the recently reviewed recommendations on indications for hand hygiene action (

5,

6). According to this model, the transmission of healthcare-associated pathogens from one patient to another or within the same patient from one body site to another via HCWs’ hands requires five sequential steps (

Figure 3.1). It is important

to recall that in addition to transfer of pathogens from the hospital environment or patient-to-patient transmission, pathogen transfer can occur within the same patient from a colonized area to a clean body site or onto an invasive medical device. Given that most healthcare-associated infections (HAIs) are of endogenous nature, this latter pathway of transmission by HCWs’ hands is of the utmost etiologic importance.

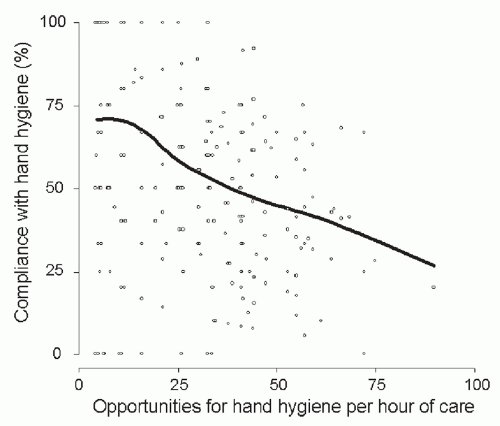

Recent epidemiologic investigations on HCWs’ compliance with hand hygiene recommendations have revealed key findings. According to the literature, in the absence of hand hygiene promotion, compliance has been unacceptably poor in many countries worldwide with mean baseline rates ranging from 5% to 89% and an overall average of about 40% (reviewed in detail in (

6) with selected subsequent references including (

13,

14,

15,

16,

17)). Very low compliance rates have been reported especially in poorly resourced settings (

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25). The predictors of poor adherence to recommended hand hygiene measures during routine patient care have been identified (

6), and include professional category (

13,

14,

15,

26,

27), hospital ward (

14,

28,

29), time of day/week (

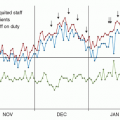

30,

31), glove use (

26,

32,

33,

34,

35), and type and intensity of patient care, defined either as the number of opportunities for hand hygiene per hour of patient care (

Figure 3.2) or patient-to-nurse ratio (

Table 3.2) (

13,

14,

28). Moreover, hand hygiene compliance is frequently poorer before patient contact than after (

6,

14,

26,

31,

36), although this is not always observed (

29).

Perceived barriers to adherence with hand hygiene guidelines have been assessed or quantified in observational studies (

6). Among others, they include skin irritation caused by hand hygiene agents (

34), inaccessible hand hygiene supplies (

13,

15), interference with HCW-patient relationships, patient needs perceived as a priority over hand hygiene, forgetfulness, lack of knowledge of guidelines, insufficient time for hand hygiene (

34), and high workload and understaffing (

Table 3.2). Adherence may be better when patients are under contact precautions (

15,

37).

HAND ANTISEPSIS AGENTS

Antiseptic agents (both soap and hand rubs) contain an antimicrobial substance, which reduces or inhibits the growth of microorganisms on living tissues. The most popular agents are briefly described below and summarized in

Table 3.3.

Amongst hand antisepsis agents, alcohols have the broadest spectrum of antimicrobial activity with excellent

in vitro and

in vivo activity against gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria (including multidrug-resistant pathogens such as methicillin-resistant

Staphylococcus aureus [MRSA] and vancomycin-resistant Enterococci [VRE]),

Mycobacterium tuberculosis, and a variety of fungi (

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47). Mycobacteria and fungi also are killed by iodophors, but less effectively by chlorhexidine, chloroxylenol, and hexachlorophene. Most enveloped (lipophilic) viruses, such as herpes simplex virus, HIV, influenza virus, respiratory syncytial virus, and vaccinia virus, are susceptible to alcohols, chlorhexidine, and iodophors (

38,

48,

49,

50,

51,

52,

53,

54,

55,

56,

57). Other enveloped viruses (hepatitis B virus and probably hepatitis C virus) are somewhat less susceptible to alcohols, but are killed by concentrations as high as 60% to 70% (v

/v) (

58). In some

in vivo studies, alcohols also showed some activity against a number of nonenveloped viruses (rotavirus, adenovirus, rhinovirus, hepatitis A virus, and enteroviruses) (

59,

60,

61,

62,

63). In general, ethanol has greater activity against viruses than isopropanol (

64). Iodophors, and to a minor extent chlorhexidine, also are active against some nonenveloped viruses. None of the listed antiseptic agents has activity against bacterial spores or protozoan oocysts. Iodophors are only slightly sporicidal, but at higher concentrations than the ones used in antiseptics (

65).

Alcohols are the most frequently used antimicrobial component of hand rubs. Alcohol-based hand rubs are considered the most effective antiseptic agents for hand hygiene, and they generally contain either ethanol, isopropanol, or

n-propanol, or a combination of two of these products. Alcohol solutions containing 60% to 80% (v/v) alcohol are most effective, with both higher and lower concentrations being less potent (

39,

40,

66). Alcohols are more effective than plain soap, and in the vast majority of trials they reduced bacterial counts on hands to a greater extent than washing hands with soaps or detergents containing hexachlorophene, povidone-iodine, 4% chlorhexidine, or triclosan (

67,

68). Several forms of alcohol-based products are available, including rinses (low-viscosity solutions), gels, and foams. The efficacy of each product should be confirmed as this will vary according to its formulation and the concentration of its active components (

6,

69,

70,

71,

72,

73,

74,

75). The WHO-recommended alcohol-based formulations contain either ethanol (80% v/v) or isopropyl alcohol (75% v/v), and can be produced locally to reduce costs (

6,

21,

76).

Chlorhexidine gluconate has been incorporated into a number of hand hygiene preparations. Aqueous or detergent formulations containing 0.5%, 0.75%, or 1% chlorhexidine are more effective than plain soap, but are less effective than antiseptic detergent preparations containing 2% and 4% chlorhexidine gluconate (

77,

78). Chlorhexidine’s immediate antimicrobial activity is slower than that of alcohols, but it has significant residual activity (

77,

78,

79,

80,

81,

82,

83,

84). Chlorhexidine resistance attributable to plasmid-borne

qacA/B genes that code for multidrug efflux pumps is being increasingly reported, though the impact of this phenomenon on the effectiveness of hand hygiene products containing chlorhexidine is not well-defined (

85,

86,

87,

88).

Iodophors are composed of elemental iodine, iodide or triiodide, and a polymer carrier of high molecular weight, such as polyvinyl pyrrolidone (povidone) and ethoxylated nonionic detergents (poloxamers) (

52,

89). Their persistent antimicrobial activity is controversial. Most iodophor preparations used for hand hygiene contain 7.5% to 10% povidone-iodine.

Chloroxylenol has been widely used in antimicrobial soaps and as a preservative in cosmetics and other products. It has good

in vitro activity against gram-positive organisms and fair activity against gram-negative bacteria, Mycobacteria, and some viruses (

1,

90,

91); in particular, the activity against

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is limited. Chloroxylenol is considered to be less rapidly active than chlorhexidine gluconate or iodophors, and its residual activity is less pronounced than that of chlorhexidine (

90,

91).

Hexachlorophene is a bisphenol contained in emulsions used for hygienic handwashing and for patient bathing. It has residual activity for several hours after use and a cumulative effect (

1,

92,

93,

94). Because of its high rates of dermal absorption and subsequent toxic effects, including neurotoxicity (

95), the agent is classified by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as not safe and effective for use as an antiseptic agent for handwashing and has been banned worldwide (

64,

96,

97).

Quaternary ammonium compounds belong to a large group; alkyl benzalkonium chlorides have been the most widely used antiseptics. They are primarily bacteriostatic and fungistatic, although microbicidal at high concentrations against some organisms (

1). They are more active against gram-positive bacteria than against gram-negative bacilli, and have relatively weak activity against Mycobacteria and fungi and greater activity against lipophilic viruses.

Triclosan is a nonionic, colorless substance that has antimicrobial activity at concentrations ranging from 0.2% to 2.0%, but tends to be bacteriostatic (

1). Like chlorhexidine, triclosan has persistent activity on the skin. According to the FDA, the available data are insufficient to classify it as safe and effective for hand antisepsis (

96).

Every new formulation for hand antisepsis should be tested for its antimicrobial efficacy to demonstrate that it has superior efficacy over normal soap or meets an agreed performance standard. The most appropriate method is to artificially contaminate volunteers’ hands with the test organism before applying the test formulation. In Europe, the most commonly used test methods are those of the European Committee for Standardization (CEN): EN 1499 (

98) for antiseptic soaps and EN 1500 (

99) for hand rubs. These use a randomized, cross-over design and compare the product with a standardized reference agent. In the United States, antiseptics are regulated by the FDA (

96), which refers to the standards of the American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM). The most frequently used method for testing hand-washing and handrubbing agents is the ASTM E-1174 (

100). The shortcomings of current test methods are discussed in detail elsewhere (

6,

73).

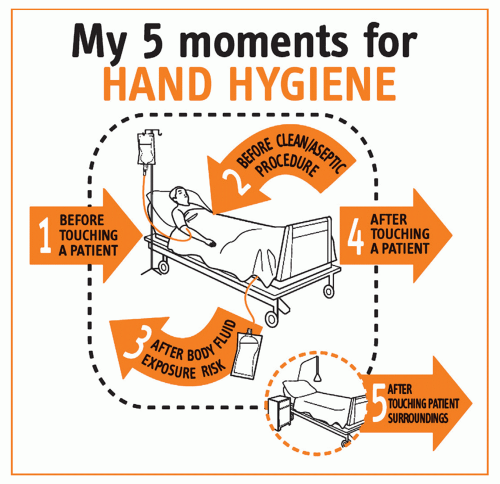

INDICATIONS FOR HAND HYGIENE DURING HEALTHCARE

Effective hand hygiene should remove transient flora on HCWs’ hands at critical moments during care activity with the clear objective to prevent cross-transmission of potentially harmful organisms and infection. A set of indications for hand hygiene has been established according to scientific evidence and is congruent with the model of transmission (see above). These indications are listed in the most recent international guidelines and graded according to supporting evidence (

Table 3.1) (

6,

101). To support their application at the point of care, a new concept was developed by WHO on the basis of expert advice and scientific evidence that condenses these indications into five moments when hand hygiene is required (

6,

102). This approach proposes a unified vision for HCWs, trainers, and observers to minimize interindividual variation and facilitate training, understanding, monitoring, and reporting of hand hygiene indications, and achieving best practices. According to this concept, HCWs are requested to clean their hands (a) before touching a patient; (b) before clean/aseptic procedures; (c) after body fluid exposure/risk; (d) after touching a patient; and (e) after touching patient surroundings. This concept has been integrated into the various WHO tools for the implementation of the WHO Guidelines (

103) and has been adopted worldwide, including in national hand hygiene guidelines (

Figure 3.3).

According to the model of transmission, hand hygiene before a patient contact or an invasive procedure is aimed at protecting the patient. In contrast, hand hygiene after tasks or contact with patients and their immediate surroundings serves to protect the HCW against colonization and infection and to prevent pathogen spread to the environment. As discussed above, HCWs more often comply with the indications after a patient contact or after a healthcare task.

For practical purposes, it is important to recognize that two or more of the listed indications might occur simultaneously during a sequence of care requiring only a single hand hygiene action. The guidelines also describe optimal techniques for handrubbing and handwashing, and specify that the latter be reserved only for situations where hands are visibly soiled, where transmission of spores is strongly suspected or proven, and after using the restroom (

6) (

Table 3.1).

Hand hygiene should be performed after glove removal because wearing gloves does not completely prevent hand contamination (

6,

26,

104,

105,

106,

107). Moreover, hand hygiene should be performed when an indication occurs, regardless of whether gloves are worn or not (

6,

12).