Clinical and Endoscopic Features

Virtually all Peutz-Jeghers hamartomatous polyps occur in the setting of the Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. Morphologically similarly polyps are rarely encountered as sporadic lesions, especially in the small intestine. Indeed, limited data suggest a relationship between sporadic Peutz-Jeghers

polyps and a variety of malignancies typically associated with the syndrome, suggesting that “isolated” Peutz-Jeghers polyps simply represent a

forme fruste of the syndrome.

1 Thus, detection of polyps that show morphologic features of Peutz-Jeghers hamartomatous lesions should prompt evaluation for a heritable syndrome and assessment for possible malignancy, particularly when they are multiple or encountered in the small intestine.

Peutz-Jeghers syndrome is an autosomal dominant hereditary polyposis syndrome affecting 1 in 200,000 persons in the United States. It is characterized by the presence of numerous gastrointestinal hamartomatous polyps, mucocutaneous pigmentation, and an increased risk for developing a variety of malignancies in multiple organ systems (

Table 5.1).

2 Diagnostic criteria for the syndrome include (1) three or more Peutz-Jeghers polyps, (2) any number of Peutz-Jeghers polyps in a patient with a family history of the syndrome, (3) characteristic mucocutaneous pigmentation in a patient with a family history of the syndrome, or (4) any number of Peutz-Jeghers polyps in association with mucocutaneous pigmentation.

3The overall risk of gastrointestinal and extraintestinal malignancy among patients with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome is estimated to be 93% by 65 years of age. Up to 12% of patients with the disorder have dysplasia and/or invasive carcinoma in their polyps, but the adjacent, nonpolypoid mucosa is also at risk for malignancy. The lifetime risk of colorectal cancer among patients with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome is 35% to 40%, followed in frequency by pancreatic cancer (35%) and gastric cancer (28%). Despite the frequent occurrence of small-intestinal polyps in Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, the lifetime risk of small bowel cancer is only 10% to 15%.

4,

5,

6 and

7Peutz-Jeghers polyps show a predilection for the small intestine, but may occur anywhere in stomach, colon, or small intestine, as well as the gallbladder, bladder, and nasopharynx.

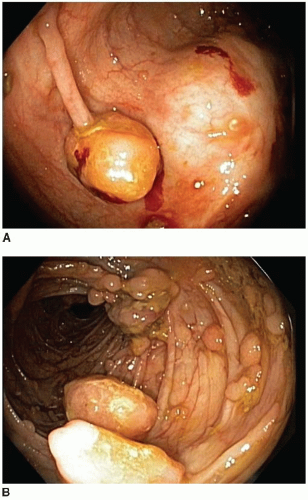

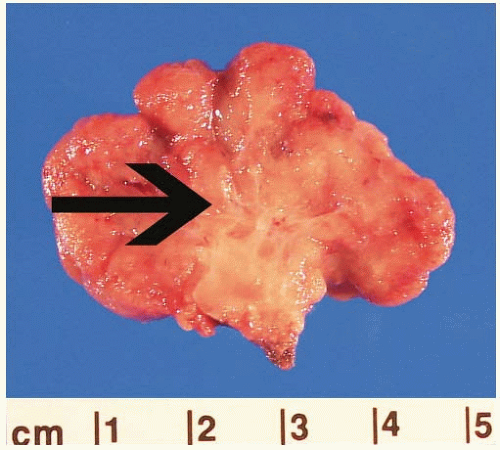

3 These polyps have a characteristic endoscopic appearance. They are multilobulated or rounded with a smooth surface that is similar in color to the background mucosa. Colorectal polyps may be pedunculated or sessile, and, when present, the stalk is usually thicker and longer than that of an adenoma (

Figure 5.2). Patients with colorectal polyps almost always have small bowel polyps as well, the latter of which tend to produce clinical symptoms of recurrent abdominal pain secondary to intussusception. Individuals less than 30 years of age typically present with symptoms reflecting benign complications of disease, such as abdominal pain or bleeding, whereas malignant complications are more common presenting manifestations among older adults.

Pathologic Features

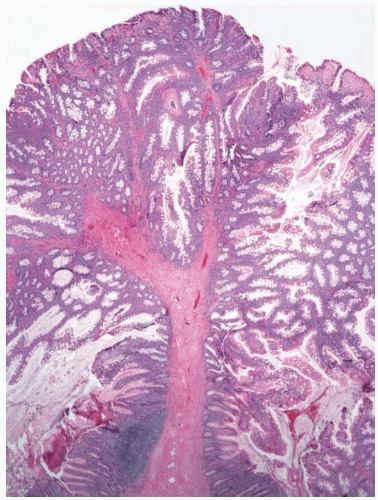

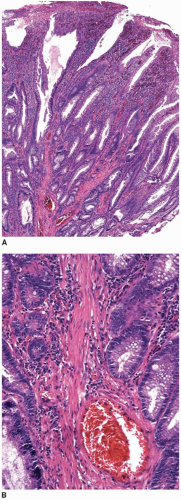

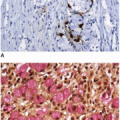

Peutz-Jeghers polyps are composed of nondysplastic mucosal aggregates and smooth muscle bundles that emanate in an arborizing fashion from the muscularis mucosae (

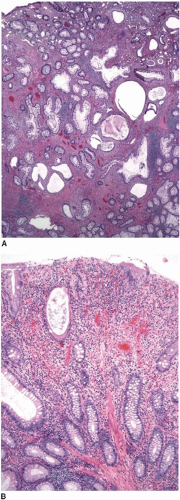

Figure 5.3). Polyps contain lobules of mature-appearing colonic epithelium supported by lamina propria (

Figure 5.4). Crypts are normal or display mildly serrated epithelium and occasional cystic dilatation. Up to 10% of small-intestinal Peutz-Jeghers polyps are associated with displaced mucosa in the submucosa, muscularis propria, or subserosa of the subjacent bowel wall. This finding likely reflects a developmental phenomenon related to their hamartomatous nature, rather than trauma-related epithelial misplacement, and is usually lacking in colorectal hamartomatous polyps.

The differential diagnosis of Peutz-Jeghers polyps includes other types of hamartomatous polyps, mucosal prolapse polyps, adenoma with misplaced (displaced) epithelium, and invasive adenocarcinoma. The morphologic features of some Peutz-Jeghers polyps overlap with those of juvenile polyps, the latter of which may be seen in association with juvenile polyposis and PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome. Overlapping features are particularly problematic among gastric and colonic Peutz-Jeghers polyps that do not show well-developed arborizing bundles of smooth muscle cells characteristic of small bowel polyps. Indeed, colonic and gastric Peutz-Jeghers hamartomas often display superimposed inflammatory changes more typically seen in juvenile polyps (

Figure 5.5).

8 Sporadic mucosal prolapse-type polyps contain abundant smooth muscle bundles extending into the lamina propria that simulate arborizing muscle bundles in Peutz-Jeghers polyps. However, prolapse-type polyps also show other features of luminal trauma, including erosions, hyperplasia and regeneration of crypts associated with ischemic-type surface epithelial changes, and inflammation (

Figure 5.6). Mucosal prolapse polyps are most commonly observed in the distal colorectum and generally develop in older adults.

Peutz-Jeghers polyps that show epithelium in the subjacent bowel wall may simulate epithelial misplacement in adenomas as well as well-differentiated adenocarcinoma. Although both Peutz-Jeghers polyps and adenomas with epithelial misplacement contain lobules of epithelium surrounded by lamina propria, those of Peutz-Jeghers polyps are unassociated with features suggestive of polyp trauma, such as hemosiderin deposits, extruded mucin, hemorrhage, or scarring. A lack of these findings, in combination with the non-neoplastic nature of the epithelium, facilitates distinction of hamartomas from adenomas with epithelial misplacement. Importantly, mural mucosal aggregates occur almost exclusively in Peutz-Jeghers polyps of the small bowel where adenomas with misplaced epithelium are uncommon. Peutz-Jeghers polyps associated with mucosal elements in the subjacent wall may also simulate invasive adenocarcinoma, particularly with the former contain epithelium that is dysplastic.

9 However, the Peutz-Jeghers polyps contain epithelium with a lobular architecture associated with lamina propria, rather than the desmoplastic stroma of an invasive carcinoma.

Molecular Alterations

More than half of patients with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome have detectable mutations in

LKB1 (STK11), including approximately 70% of patients with inherited disease and 30% to 70% of those who are the first affected family members to be identified. This gene is located on

chromosome 19p13.3 and encodes a nuclear serine threonine kinase that normally inhibits cell growth by stimulating the promoter activity of

p27.

10,

11,

12 and

13 The disease phenotype tends to be more severe in patients with truncating mutations compared to missense mutations.

11