III. PREVENTION AND EARLY DETECTION OF CERVICAL CANCER

A. Vaccination. Bivalent (HPV 16/18) and quadrivalent HPV 6/11/16/18 vaccines have shown efficacy by demonstrating protection against CIN, persistent HPV, and external genital warts in double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trials. The vaccines are well tolerated, and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), in conjunction with the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), recommends administration of approved vaccines from ages 9 to 26. The exact duration of immunity offered by this vaccine is unknown, but is demonstrated to be up to 8.5 years following vaccination against HPV 16. The HPV vaccine does not eliminate the need for cervical cytology screening.

B. Screening with Pap testing

Most patients with cervical cancer do not have symptoms, and cases are detected by routine Pap test screening.

1. Frequency. For >50 years, the Papanicolaou, or Pap, test has been used as the main screening tool for cervical diseases. Early detection has greatly reduced the morbidity and mortality of cervical cancer. The conventional Pap smear has been shown to have a sensitivity of approximately 50%. Overall, it is estimated that about two-thirds of the false-negative rates are due to sampling error, and the remaining one-third are due to laboratory detection error. The American Cancer Society’s recommendations for Pap testing are as follows:

a. Women should have yearly Pap smears starting at age 21 or 3 years after the onset of sexual activity,

b. Women older than 30 and at low risk for cervical cancer who have never had a significant abnormality may have the test less often, for example, every 2 to 3 years, if she has had three normal tests in a row.

c. Women who have had their uterus removed for benign indications do not need to have regular Pap tests. In postmenopausal patients who are ≥70 years of age, screening may be stopped in the presence of three consecutively normal and satisfactory Pap smears and in the absence of an abnormal Pap test over the last 10 years.

2. Technique. There are many problems that contribute to the low sensitivity of Pap tests. Some of these include sample adequacy, slide preparation, and slide interpretation. The new technologies are aimed at improving the quality of the samples but they do not improve the detection of cervical cancer. The squamocolumnar junction, where cervical cancer arises, recedes upward and inward with advancing age. This process decreases the usefulness of scrapings alone to make the diagnosis.

a. Conventional Pap smears. When performing the conventional Pap smear, the cytobrush, used together with an extended tip spatula, is the most effective combination for cell collection. The specimens are smeared on clean glass slides and fixed immediately.

b. Liquid-based Pap smears. This technique involves thin-layer, liquid-based systems. The cervical sample is taken and suspended in an alcohol-based preservative solution. In this liquid, the blood, mucus, and inflammatory cells are filtered out. In the laboratory, a representative sample of cells is then deposited by an automatic device on the slide. The slide is then stained and screened in the usual manner. This specimen can be used for detection of HPV, and “reflex” HPV testing can be performed if cytology reveals evidence of atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASC-US). ThinPrep and SurePath are the two liquid-based cytology systems that are approved by the Federal Drug Administration (FDA).

3. Pap smears are graded using the 2001 Bethesda system as follows:

Negative for Intraepithelial Lesion or Malignancy

Epithelial Cell Abnormalities Squamous Cell

Atypical squamous cells (ASC)

Of undetermined significance (ASC-US)

Cannot exclude HSIL (ASC-H)

Low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (LSIL)

Encompassing: human papillomavirus (HPV)/mild dysplasia/cervical intraepithelial neoplasia type 1 (CIN 1)

High-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL)

Encompassing: moderate and severe dysplasia, carcinoma in situ (CIS)/CIN 2 and CIN 3

With features suspicious for invasion

Glandular Cell

Endocervical cells (not otherwise specified, NOS)

Endometrial cells (NOS)

Glandular cells (NOS)

Atypical

Endocervical cells, favor neoplastic

Glandular cells, favor neoplastic

Endocervical adenocarcinoma in situ

Adenocarcinoma

Endocervical

Endometrial

Extrauterine

Not otherwise specified (NOS)

Other Malignant Neoplasms

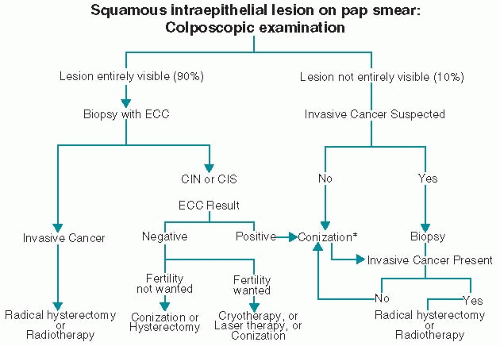

VI. MANAGEMENT

A. Dysplasia/cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) 1-3. Treatment modalities include superficial ablative therapies, LEEP, cone biopsy, and hysterectomy (

Fig. 11.1).

1. CIN 1 lesions may be observed if the patient has good follow-up because of the high rate of spontaneous regression of these lesions, or lesions may be treated with ablative therapy. In young patients, especially adolescents, CIN 2 may be followed expectantly.

2. Patients with high-grade (CIN 2 and 3) squamous lesions are suitable for ablative or resection therapies, provided the entire transformation zone is visible on colposcopy, the histology of the biopsies is consistent with the Pap smear, the ECC is negative, and there is no suspicion of occult invasion.

3. For high-grade lesions, we recommend LEEP, which involves the use of wire loop electrodes with radiofrequency alternating current to excise the transformation zone under local anesthesia. This has become the preferred treatment for high-grade CIN that can be adequately assessed by colposcopy. Ablative techniques include cryosurgery, carbon dioxide laser therapy, and electrocoagulation diathermy, which are now less frequently employed.

4. Cone biopsy with a scalpel is preferred for lesions that cannot be assessed colposcopically or when adenocarcinoma in situ is suspected.

5. If the patient has other gynecologic indications for hysterectomy, a vaginal or an extrafascial (type I) abdominal hysterectomy may be performed.

B. Invasive cervical cancer: Stage I disease (

Table 11.3). The management of patients with early carcinoma of the cervix is diagrammed in

Figure 11.1 and summarized in

Table 11.3.

1. Stage Ia1 disease with <3-mm invasion may be treated with excisional conization, provided the lesion has a diameter of <7 mm and no lymph or vascular space invasion. A vaginal or extrafascial hysterectomy is also appropriate if further childbearing is not desired.

2. Stage Ia2 disease. For patients with stage Ia2 disease and 3 to 5 mm of stromal invasion the risk for nodal metastases is 5% to 10%. Bilateral pelvic lymphadenectomy should be performed in conjunction with a modified radical (type II) hysterectomy. If future childbearing is desired, in selected cases with well-differentiated tumors, radical trachelectomy with pelvic lymphadenectomy may be considered.

3. Stage Ib disease carries a 15% to 25% risk for positive pelvic lymph nodes and should be treated with a type II or radical (type III) hysterectomy, bilateral pelvic lymphadenectomy, and para-aortic lymph node evaluation. In patients who are poor surgical candidates or in whom the tumor is large (generally >4 cm), RT in conjunction with cisplatin chemosensitization is preferred. In patients with high-risk features (e.g., lymph node metastasis), postoperative RT with concurrent chemotherapy (CCT) with cisplatin as a radiation sensitizer should be given. Fertility preservation with a radical trachelectomy and pelvic lymphadenectomy may be considered if tumors are <2 cm and well differentiated with no evidence of lymph-vascular space invasion.

C. Concurrent chemotherapy (CCT) with RT reduces recurrence by 30% to 50% and improves 3-year survival rates by 10% to 15% over adjuvant treatment with RT alone.

1. CCT is indicated in the following circumstances:

a. High-risk stages I to IIa (e.g., with lymph node involvement or positive margins)

b. Stages IIb, III, and IVa

2. Point A and point B are common terms used in the management of cervical cancer. Point A is 2 cm proximal and 2 cm lateral to the cervical os. Point B is 3 cm lateral to point A.

3. Regimens. Several combination chemotherapy regimens involving cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) have been effective. Representative regimens are as follows:

a. Cisplatin, 40 mg/m2 weekly for 6 weeks (with or without 5-FU infusions)

b. Cisplatin, 50 mg/m2 on days 1 and 29, and 5-FU, 1,000 mg/m2 per day by continuous IV infusion for 4 days beginning on days 1 and 29. Extension of treatment to four courses is being investigated.

D. Stage II disease. Stage IIa disease is treated in the same manner as stage Ib disease. When the tumor extends to parametrium (IIb), patients should be treated with RT and CCT involving cisplatin (see Section VI.C).

E. Stage IIb and III disease. When the parametrium (IIb), the distal vagina (IIIa), or the pelvic sidewall (IIIb) is involved, clear surgical margins are not possible to achieve, and patients should be treated with maximum-dose (8,500 cGy) RT delivered both externally and by brachytherapy. CCT with cisplatin as radiation sensitizers improves survival rates when compared with RT alone (see Section VI.C).

F. Recurrent and stage IV disease. Advanced cancer in the pelvis is discussed in “General Aspects,” Section III, and obstructive uropathy is discussed in

Chapter 31.

1. Lower vaginal recurrence can occasionally be cured by RT or exenteration.

2. Pelvic exenteration. A pelvic exenteration may also be considered for central pelvic recurrent disease after primary RT when spread is confined to the bladder or rectum. Exenteration carries a higher morbidity rate. Metastatic cancer outside the pelvis and poor medical condition of the patient are contraindications to exenteration. Ureteral obstruction, leg edema, and sciatic pain usually suggest sidewall disease. Surgery should be abandoned if there is more extensive cancer than was clinically suspected.

3. RT alone or with chemotherapeutic sensitizers can occasionally cure stage IVA disease. External-beam RT is combined with intracavitary or interstitial radiation to a total dose of about 8,500 cGy. If disease persists after chemoradiation, pelvic exenteration can be performed.

4. Chemotherapy for metastatic disease is not curative. Distant metastases or incurable local disease should be treated as for any advanced malignancy. A number of chemotherapeutic drugs (e.g., cisplatin, carboplatin, paclitaxel, topotecan) produce short-term responses in 10% to 30% of patients.

G. Complications of surgery or RT

1. LEEP. Bleeding occurs in 1% to 8% of cases, cervical stenosis occurs in 1%, and pelvic cellulitis or adnexal abscess occurs rarely.

2. Conization. Hemorrhage, sepsis, infertility, stenosis, and cervical incompetence occur rarely.

3. Radical hysterectomy. Acute complications include blood loss (average, 800 mL), urinary tract fistulas (1% to 3%), pulmonary embolus (1% to 2%), small bowel obstruction (1%), and febrile morbidity (25% to 50%). Subacute complications include transient bladder dysfunction (30%) and lymphocyst formation (<5%). Chronic complications include bladder hypotonia or atonia (3%) and, rarely, ureteral strictures.

4. Pelvic exenteration. The surgical mortality rate is <1%. The postoperative recuperative period may be as long as 3 months, and the massive fluid shifts and hemodynamic status that sometimes occur may require monitoring. Most postoperative morbidity and mortality result from sepsis, pulmonary embolism, wound dehiscence, and intestinal complications, including small bowel obstruction and fistula formation. A reduction in gastrointestinal

complications can be achieved by using unirradiated segments of bowel and closing pelvic floor defects with omentum. The 5-year survival rate for patients undergoing total pelvic exenteration is 30% to 50%.

5. Pelvic irradiation. Radiation proctitis and enteritis with intractable diarrhea or obstruction, cystitis, sexual dysfunction because of vaginal stenosis and loss of secretions, loss of ovarian function, fistula formation, and 0.5% mortality either from intractable small bowel injury or from pelvic sepsis (see “

General Aspects,” Section IV).