Major Concepts

Diseases

Infections caused by group A streptococcus (GAS) bacteria are common throughout the world and result in a wide variety of illnesses, ranging from mild to debilitating or lethal. The rate of incidence of the more severe, invasive GAS infections, such as necrotizing fasciitis and streptococcal toxic shock syndrome (STSS), peaks and ebbs over time and has increased significantly in developed countries since the 1980s. Other potentially severe manifestations of GAS infection include erysipelas, scarlet fever, meningitis, rheumatic fever, acute glomerulonephritis, and childbed fever.

Infection

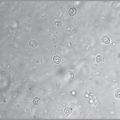

GAS (Streptococcus pyogenes) bacteria are gram-positive cocci that characteristically lead to β-hemolysis on sheep blood agar. They are common residents of the skin and throat and may enter the body through skin breaks or respiratory secretions or via contaminated food or drink. Different strains of these bacteria possess different virulence factors, a number of which are controlled by the mga gene, which up-regulates their expression. A particularly important virulence factor is the M protein which is required for adherence to target cells, such as skin keratinocytes, and resistance to phagocytosis. GAS also encode several exotoxins, which contribute to the disease process by inducing pathogenic overstimulation of the immune system or disrupting the extracellular matrix, resulting in damage to soft tissues.

Immune Response

GAS have several means of avoiding destruction by the innate and adaptive arms of the immune system, including phagocytosis, the complement cascade, and neutralizing antibodies. They also cause harmful immune responses, such as the overproduction of inflammatory cytokines during STSS, and autoimmune reactions during rheumatic fever and acute glomerulonephritis. Care must be taken during vaccine development to avoid the induction of such pathogenic immunity.

Treatment

Early treatment with antibiotics, particularly penicillin, is often effective in eliminating most strains of GAS and decreasing the risk for serious disease manifestations. Individuals who are allergic to penicillin may be treated with erythromycin, cephalexin or cephradine, or macrolides. Drug resistance, however, is becoming increasingly common; a sizable number of GAS strains are resistant to tetracycline, and resistance to erythromycin and macrolides is increasing. Newer drugs, such as telithromycin, are effective against some of these strains. Other treatment options include administration of massive amounts of intravenous fluids for individuals with severe hypotension, extensive debridement for those with necrotizing fasciitis, and absolute bed rest and anti-inflammatory drugs for those with rheumatic fever.

Prevention

Preventive measures include basic hygienic practices, such as hand-washing after coughing or sneezing and before eating to prevent infection by respiratory secretions or contaminated food. Pasteurization of milk and the exclusion of persons with skin lesions from food preparation are also effective means of decreasing GAS infection. Objects used in such medical procedures as liposuction, hysterectomy, childbirth, and bone pinning need to be disinfected to avoid noscomial transmission.

Some 10,000 to 15,000 cases of invasive group A streptococcus (GAS) infections occur in the United States each year, resulting in 2,000 deaths. GAS causes a variety of diseases, ranging in severity from mild to life-threatening. These conditions include streptococcal septic sore throat (strep throat); pharyngitis; tonsillitis; impetigo; erysipelas; scarlet fever; meningitis; necrotizing fasciitis, myositis, and myonecrosis; rheumatic fever, myocarditis, and valvulitis; acute glomerulonephritis; childbed fever; streptococcal toxic shock syndrome (STSS); otitis media; pneumonia; and septicemia. GAS infections result in 500 to 1,500 cases of necrotizing fasciitis in the United States yearly. Increased morbidity and mortality in recent decades have resulted in the classification of GAS infections as reemerging diseases. Annual costs in the United States due to strep throat alone approach $1 billion. Antibiotics have greatly reduced the incidence of rheumatic fever, an autoimmune complication of GAS infection, in the developed world, but it remains a major health factor in underdeveloped nations. Although some of the illnesses associated with GAS infections are mild, the consequences of invasive GAS may be very serious, and the overall mortality rate is 21%, complicated by the development of drug resistance in children and adults. The incidence of invasive GAS among individuals who inject illegal drugs is increasing.

Some of the diseases associated with GAS infections have been known since antiquity and periodically shift their severity. In 1664, Thomas Sydenham described “febris scarlatina.” A major epidemic of this condition, scarlet fever, occurred in 1736 in the American colonies, ultimately claiming the lives of 4,000 people. For centuries prior to this time, scarlet fever had existed either endemically or as relatively mild epidemics separated by long periods of time. Between the years 1825 and 1885, however, a series of cyclical and frequently highly lethal epidemics began in various urban centers, including Paris, London, Dublin, and New York City. The mortality rate in some of these outbreaks approached 30%. After that, the severity of scarlet fever decreased in developed regions.

The Greek physician Hippocrates recorded a disease that meets the clinical description of necrotizing fasciitis. This condition was first described in the United States by a Confederate Army surgeon during the American Civil War. It was determined to be of bacterial origin in 1918 and received its current name in 1952. During the 1800s and 1900s, necrotizing fasciitis occurred only sporadically, primarily in military hospitals during conflicts. It increased in virulence in the United States during the 1980s due to the emergence of toxin-producing strains, and by 1999, approximately 600 cases of this serious condition had been reported in the United States.

A decreased incidence of severe invasive GAS infections occurred in the United States during the 1930s, when mortality rates fell from 72% to between 7% and 27% even prior to the introduction to antibiotics. This was not accompanied by a decline in mild disease manifestations or in the prevalence of GAS colonization and infection. Developing regions of the world continued to suffer from highly pathogenic infections. The more lethal expressions of GAS inexplicably rebounded in developed nations throughout the world in the 1980s (with mortality rates ranging from 35% to 48%) as these bacteria reemerged as modern killers. Jim Henson, the creator of the Muppets, died of STSS. Other conditions caused by GAS bacteria have been known for millennia but have reemerged in recent decades. One such condition is necrotizing fasciitis, an extremely rapid pathogenic destruction of connective tissue and fat that may be lethal if not treated promptly. It is caused by the so-called flesh-eating bacteria. This condition was described by Hippocrates in ancient Greece, but the numbers of cases have greatly increased recently and periodically receive much attention in the popular press.

Major epidemics of rheumatic fever struck the U.S. military during World War II and the Korean War. Large numbers of cases also occurred in Utah between 1985 and 1998.

GAS infection results in a wide variety of conditions, some of which are minor (sore throat, tonsillitis, and impetigo), while others (rheumatic fever, necrotizing fasciitis, and streptococcal toxic shock syndrome) may result in long-term disability or death. People are more likely to develop serious illnesses caused by invasive GAS infection if they have skin lesions (including chickenpox or cuts), cancer, diabetes, or a skin ulcer or if they abuse drugs or are using steroids. The elderly are also at increased risk. GAS infections occur year round, but incidence peaks in late winter and early spring.

Entry into the respiratory tract is followed by a 36- to 72-hour latent period. As the bacteria grow, they induce a sore throat, inflammation of the pharynx and tonsils (pharyngitis and tonsillitis) with or without exudate, fever, and leukocytosis (increased white blood cell count). Severe, uncomplicated streptococcal pharyngitis typically diminishes after five to seven days. Before the development of penicillin, the death rate from this disease manifestation was 1% to 3%.

Table 6.1 Diseases associated with GAS infection

| Disease | Symptoms | Persons Affected |

| Impetigo | Reddened skin, fluid-filled blisters | Children |

| Scarlet fever | Sore throat, fever, and rash; “scarlet tongue”; nausea and vomiting | Children |

| Erysipelas | Acute cellulitis: fever; chills; leukocytosis; lymphadenopathy; painful, fiery red skin lesion | Infants and persons over the age of 20 years |

| Necrotizing fasciitis | Fever, severe pain, swelling, extreme thirst, diarrhea, nausea, confusion, dizziness, gangrene with extensive necrosis of tissues over large areas of skin, septic shock | Young, healthy adults |

| Rheumatic fever | Fever, inflammation of joints and heart valves, myocarditis, erythema marginatum, Sydenham’s chorea | Persons aged 3–15 years |

| Acute glomerulonephritis | Inflammation of glomeruli (filtering tubules of the kidneys) | All |

| Childbed fever | Fever | Women following childbirth |

| Streptococcal toxic shock syndrome (STSS) | Fever, chills, myalgia, dizziness, confusion, severe abdominal pain, vomiting, diarrhea, hypotension, shock, generalized erythematous macular rash; acute respiratory distress syndrome, renal failure, disseminated intravascular coagulation | All |

Impetigo

Impetigo is a superficial skin infection occurring primarily in children, usually in the late summer or fall in hot climates. This condition is characterized by reddened skin and fluid-filled blisters, mainly on the legs and arms and around the nose and mouth. These blisters later burst, releasing a thin, yellowish fluid. Fever is usually absent. Following antibiotic therapy, the prognosis is excellent. Several million cases occur each year in the United States.

Scarlet Fever

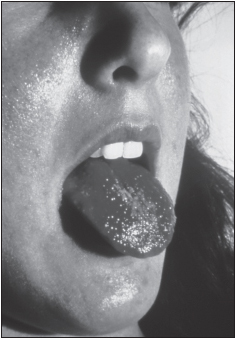

Scarlet fever usually occurs in children and is most commonly found in temperate zones and slightly less frequently in subtropical regions. It typically manifests as sore throat, fever, and rash in response to a pyrogenic exotoxin. The rash begins as a mass of tiny red spots on the neck and upper trunk and then spreads to other parts of the body, including the inner surfaces of the thighs and the folds of the axillae (armpits), elbows, and groin. The tongue may be covered with a white coating containing red spots; the coating later peels away to give a bright-red appearance (strawberry tongue). A peeling of skin, particularly the tips of the fingers and toes, may occur during convalescence. Severe infections may be accompanied by high fever, nausea, and vomiting. Scarlet fever may be a very severe condition, resulting in large and lethal epidemics. Highly virulent strains of GAS resulted in mortality rates of 25% to 35% among children during the 1880s, but current rates are much lower.

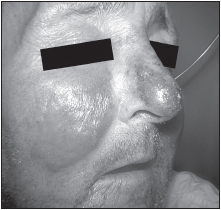

Erysipelas

Erysipelas is a recurrent form of acute cellulitis commonly located on the legs or the face. The symptoms are fever and chills, blisters, leukocytosis (elevated white blood cell count), lymphadenopathy (swollen lymph nodes), and a painful, fiery red, spreading skin lesion with a raised border. Bacteremia may be present. Although the prognosis is generally good following antibiotic therapy, erysipelas may be severe or fatal in individuals who are debilitated. It develops most commonly in infants and persons over the age of 20 years.

Necrotizing Fasciitis

Necrotizing fasciitis has also been known as malignant ulcer, putrid ulcer, gangrenous ulcer, and hospital gangrene. It is the rapid, extremely dangerous destruction of fascia (connective tissue) and other soft tissue following infection by “flesh-eating bacteria”—often GAS but sometimes Clostridium perfringes or other bacteria. Infection with these bacteria often occurs at the site of an insignificant trauma during common activities, such as a scratch from a rose thorn during gardening. The destruction of fascia and fat (adipose tissue) begin within hours of infection by GAS. Early symptoms include fever, severe pain, swelling, redness at the wound site, extreme thirst, diarrhea, nausea, confusion, and dizziness. Over next two days, the wound becomes a purplish or bluish color with blisters containing a clear yellow fluid. Two or three days after that, gangrene develops, with extensive necrosis of the underlying tissues occurring in the next week over large areas of skin. Potent toxins render the patients unresponsive or delirious. Afflicted persons may lose consciousness and develop septic shock due to severe decreases in blood pressure. Some 500 to 1,500 cases of this condition are reported in the United States each year. Even after extensive debridement and irrigation of the wound (removal of dead material and washing), the fatality rate is 20%.

This disease manifestation most often occurs in young, strong persons following minor skin trauma rather than in older people with multiple medical problems. It is rare in children. The increased incidence of this disease may reflect the appearance of more virulent GAS strains. The development of necrotizing fasciitis is associated with immunosuppression in 91% of the cases, especially among persons with diabetes, alcoholism, end-stage renal disease, cancer, and malnutrition; persons using immunosuppressants; and women during the peripartum period occurring around the time of childbirth.

Current cases of necrotizing fasciitis are more likely to display systemic manifestations (shock or organ failure) associated with STSS than previously, even after antibiotic therapy. Another worrisome finding has been the increase in reports of myositis or myonecrosis in conjunction with GAS infections. These manifestations, with destructive damage to muscles and tendons, occur either alone or accompanying necrotizing fasciitis.

Rheumatic Fever

Rheumatic fever

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree