Giant Cell Tumor of Bone

Sean V. McGarry

C. Parker Gibbs

Giant cell tumor (GCT) of bone is a benign but often aggressive tumor. It remains one of the most challenging of the benign bone tumors to treat. It is also unique from all other benign bone tumors except chondroblastoma in that it can metastasize. Metastases from GCT of bone almost always arise in the lung and rarely are fatal or cause significant morbidity at the site of metastasis.

Pathogenesis

Etiology

Etiology is unclear.

Epidemiology

5% to 10% of all bone tumors

Female:male 1.3 to 1.5:1

Age distribution

Rare prior to skeletal maturity

Most (∼75%) occur between 18 and 40 years.

Skeletal distribution

Nearly always involve epiphysis, but epicenter is in metaphysis

Rare pediatric giant cell tumors are metaphyseal but may erode across physis into epiphysis.

Can occur in nearly any bone in the skeleton

Most common sites of occurrence (half of all lesions occur about the knee)

Distal femur

Proximal tibia

Distal radius

Sacrum (anterior body)

Proximal humerus

Proximal femur

Distal tibia

Rare in small bones of hands and feet

Pathophysiology

The cell of origin in GCT of bone is unknown, although immunohistochemical studies have suggested that the cells are of a histiocytic nature. More recently, the stromal cells have been suggested to be of osteoblastic lineage based on their expression of alkaline phosphatase, osteocalcin, and Cbfa1.

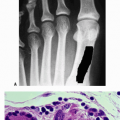

The stromal cells are thought to produce RANKL, which leads to osteoclastogenesis, which in turn leads to osteolytic destruction of bone (Fig. 5.6-1). GCT of bone was at one time described as osteoclastoma. The destructive nature of GCT, in combination with its typical location in the epiphysis, explains the clinical course. The articular cartilage is initially spared. The lesion spreads across the epiphysis and eventually destroys the cortex and can form a soft tissue mass. Without the structural support of the underlying subchondral bone, pathologic fractures through the articular surface are not uncommon. Unchecked, this leads to severe secondary degenerative changes.

The stromal cells are thought to produce RANKL, which leads to osteoclastogenesis, which in turn leads to osteolytic destruction of bone (Fig. 5.6-1). GCT of bone was at one time described as osteoclastoma. The destructive nature of GCT, in combination with its typical location in the epiphysis, explains the clinical course. The articular cartilage is initially spared. The lesion spreads across the epiphysis and eventually destroys the cortex and can form a soft tissue mass. Without the structural support of the underlying subchondral bone, pathologic fractures through the articular surface are not uncommon. Unchecked, this leads to severe secondary degenerative changes.

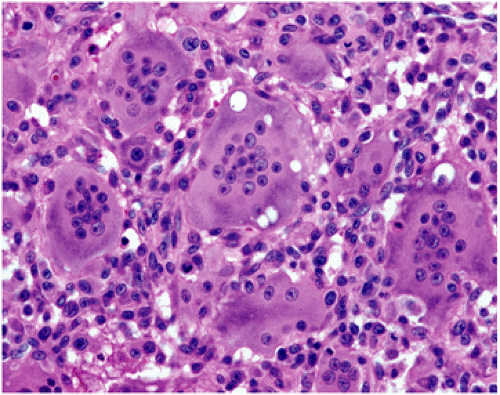

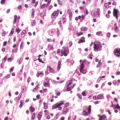

Histopathology (Fig. 5.6-1)

Dense cellular pattern of monocytes admixed with numerous giant cells

Nuclei of the monocytes appear identical to the nuclei in the giant cells.

Classification

Following Enneking’s classification of benign tumors, GCT of bone is most commonly active or aggressive.

Latent: rare in GCT

Active: any symptomatic or growing lesion

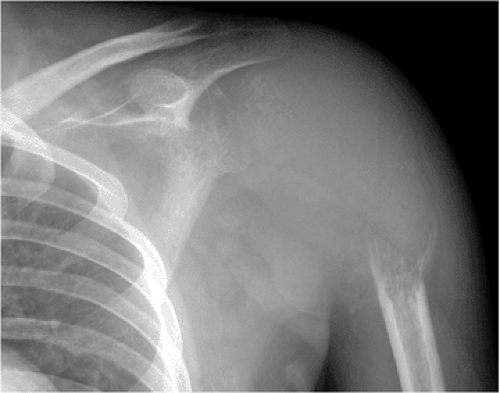

Aggressive (Fig. 5.6-2)

GCT is probably the most aggressive of the benign tumors.

Radiographically lesions can be extremely destructive of bone, resembling osteosarcoma.

Along with aneurysmal bone cyst and chondroblastoma, GCT is one of the three classically aggressive benign bone tumors.

GCT defies the classic definition of benign tumors in that it can metastasize, although it does so rarely.

One of only two benign bone tumors that metastasize: GCT and chondroblastoma

Diagnosis

The radiographic findings associated with GCT are often strongly suggestive of the diagnosis.

Other benign lesions in the differential would include chondroblastoma and aneurysmal bone cyst (ABC), although chondroblastomas are more common in the skeletally immature patient and are usually isolated to the epiphysis, and an epiphyseal location would be unusual for the ABC.

Aggressive GCT can be mistaken for any of the primary or secondary bone malignancies that may extend into the epiphysis (telangiectatic or fibroblastic osteosarcoma, Ewing sarcoma, or metastatic disease).

Clear cell chondrosarcoma is the one malignancy that classically occurs in an epiphyseal location and should be considered in the differential diagnosis.

Physical Examination and History

Clinical Features

Generally relate to the extent of the joint involvement

Patients initially present with dull achy pain of the involved joint.

Extension of the lesion into the soft tissues and physical examination consistent with a soft tissue mass are relatively late findings.

Extension of the lesion into the joint is unusual and is associated with complaints similar to osteoarthritis.

Radiologic Features (Fig. 5.6-3)

Epiphyseal location: lesion is centered in the metaphysis of long bones but in skeletally mature patients uniformly involves the epiphysis and frequently extends to the subchondral bone

Radiolucent: GCT is uniformly destructive of bone without matrix mineralization

Eccentric: initially GCT is eccentric but spreads across the epiphysis with progression

Extension to articular cartilage: extends to the subchondral bone, but initially preserves the joint

Confined to bone: late spread breaks through the cortex

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree