Fifteen-variable trauma-specific frailty index

Comorbidities

Cancer history

Yes (1)

No (0)

PCI (0.5)

Coronary heart disease

MI (1)

CABG (0.75)

Medication (0.25)

None (0)

Dementia

Severe (1)

Moderate (0.5)

Mild (0.25)

No (0)

Daily activities

Help with grooming

Yes (1)

No (0)

Help managing money

Yes (1)

No (0)

Help doing housework

Yes (1)

No (0)

Help toileting

Yes (1)

No (0)

Help walking

Wheelchair (1)

Walker (0.75)

Cane (0.5)

No (0)

Health attitude

Feel less useful

Most time (1)

Sometimes (0.5)

Never (0)

Feel sad

Most time (1)

Sometimes (0.5)

Never (0)

Feel effort to do everything

Most time (1)

Sometimes (0.5)

Never (0)

Falls

Most time (1)

Sometimes (0.5)

Never (0)

Feel lonely

Most time (1)

Sometimes (0.5)

Never (0)

Function

Sexual active

Yes (0)

No (1)

Nutrition

Albumin

<3 (1)

>3 (0)

12.3.5 Management of Geriatric Trauma Patients

The ongoing management of geriatric trauma patients involves several domains, including identification of patient’s baseline status (pre-injury), patient/family’s goals of care, patient’s anticipated prognosis and recovery, and early and ongoing discharge planning. Close monitoring is essential for early identification and management of associated injuries and impact of comorbidities and medications. Comprehensive delirium prevention and management protocols should be implemented (see Chap. 2, Delirium). Careful analgesia is important to optimize patient’s functioning and reduce the incidence of delirium. Optimizing cognition, sleep, nutrition, managing constipation, and preventing skin breakdown are key elements of care. Collaboration with geriatricians (in consultation or co-management models) and/or palliative care teams offers the opportunity to optimize care and improve clinical outcomes for older adults.

12.3.6 Outcomes of Care for Geriatric Trauma Patients

During the past couple of decades, quality of healthcare services and outcomes has become increasingly important. Outcomes including in-hospital mortality (IHM), post-hospitalization mortality (PMH), in-hospital complications, functional status, and ICU and hospital length of stay have been extensively studied in geriatric patients. Multiple factors help determine these outcomes in geriatric trauma patients such as demographics, injury severity, and general clinical condition, which is a cumulative effect of age, comorbidities, decline in physiologic reserve, cognition, and functional ability of the patient. Elderly patients who are admitted to the hospital for an acute illness or after a traumatic injury are more prone to develop functional disability and be discharged to skilled nursing facilities for long-term care than younger adults. It has been reported that more than 90 % of geriatric trauma patients require skilled nursing care facilities at least 1 year after the injury. Complications resulting from a functional decline after injury include loss of independence, falls, incontinence, depression, malnutrition, and lack of socialization. Early evaluation of general clinical condition, injury severity, functional and cognitive impairments through a team assessment can enable a rapid and appropriate management utilizing geriatric principles to minimize the risk of adverse outcomes.

12.3.7 Transition of Care

The primary objective for any trauma patient admitted to the hospital is safe transition to a level of care that meets their needs and goals of care, and allows for the highest level of independence. The discharge site may be their home (often with family and home health services support) or an inpatient facility (including skilled nursing facility or rehabilitation hospital). A successful transfer requires comprehensive planning that should begin at the time of hospital admission and demands the early and ongoing assessment of patient’s physical, cognitive, social, and financial situation by the physician, nurse, case manager, therapist, and the social worker. The discharge of these patients to these facilities is often limited by the financial restrictions, insurance coverage laws, reimbursement rules, and CMS regulations. These issues require a close communication among the health care providers, case manager, and social worker to allow a timely and appropriate discharge of these patients. An appropriate discharge plan is essential to ensure patient safety, to idealize patient outcomes, and to prevent readmissions.

A key element of the disposition of the patient is the assessment of functions associated with activities of daily life. The most commonly utilized tool to assess and document functional independence is Functional Independence Measure (FIM) instrument. It is composed of 18 elements which assesses 13 motor skills and 5 cognitive skills, each scaled from 1 to 7 with 1 meaning total assistance and 7 meaning total independence. This score is the most widely accepted and utilized of all functional assessment tools and also recognized by the CMS.

12.3.7.1 Key Points

Transition of care from the hospital is challenging as a large number of geriatric patients require transfer to a rehab facility or a skilled nursing facility.

Close communication and a strong working relationship among the health care providers are essential to ensure a safe and appropriate discharge of these patients.

12.3.8 End-of-Life Care in Older Adults

Withdrawal of care is a common occurrence in the geriatric trauma patients who are admitted to the ICU. Despite its frequency, it remains a complicated and challenging situation for health care providers. Most common causes for withdrawal of care include reduction of patient suffering, anticipated poor quality of life, and brain death [28]. It is important to understand that withdrawal of care should not always be viewed as a symbol of failure or defeat. Understanding the issues associated with end-of-life situations and palliative care is of paramount importance to improve the care of dying patients.

A patient-centered approach should be utilized to establish the goals of the treatment in geriatric patients. This requires an in-depth discussion with the patient and their families about the likely outcomes and subsequent quality of life. There are numerous prognostic models that predict mortality and may help in informed decision making, however none of these models are 100 % accurate. The decision for withdrawal of care should be based on risk-benefit analysis and patient’s autonomy and wishes.

While advising patients and their families in arriving at a decision, there should be ongoing communication and a consensus should be achieved before reaching a final decision. One of the most significant concerns for patients and their families regards symptoms of pain, nausea, agitation, and respiratory decline in the final stages of life. While talking to the family, it is essential to understand what the family knows and what they wish to understand, and then communicate the information they need to make an informed decision. These decisions can cause significant distress and grief for the family so the physicians should understand their feelings, express empathy, and offer their support. The hallmark of palliative care is the relief of these symptoms to ensure that the patient is comfortable during the final days, and this should be discussed with patients and their families. Although all trauma/acute care surgeons should be skilled in these conversations, collaboration with a palliative care team is strongly recommended. Chapter 6, Palliative Care and End of Life Issues , provides an in-depth discussion of this subject.

12.3.8.1 Key Points

End-of-life decisions and withdrawal of care remains a challenge for geriatric patients.

A patient-centered approach should be exercised to establish the goals of the treatment.

An honest open communication between patients, their families, and caregivers is the cornerstone for high quality end-of-life care decisions.

12.4 Geriatric Emergency General Surgery

Emergency general surgery includes a diverse range of disorders that often presents a unique diagnostic and therapeutic challenge for the caregivers. Aging is associated with anatomical and physiological changes that further complicate the management of emergency general surgery in the elderly population. As the US population continues to age, the acute care surgeons are likely to see an increase number of these patients. It is essential for acute care surgeons to have a thorough understanding of the differences in the disease process, its presentation, and management to provide optimal care for these patients.

12.4.1 Clinical Presentation of Elderly Patients

Primary evaluation of the elderly patient with a suspected surgical emergency is challenging. Presentation of the elderly patients is often atypical, delayed, and vague. Preexisting cognitive impairment or neurologic deficits (i.e., dementia, delirium, prior stroke, and neuropathy) are contributing factors for the atypical or delayed presentation of the patient or the ability to be detected by primary care providers [29]. Moreover, the history of present illness may be difficult to obtain as it is often complex, deficient, and imprecise. Physical examination similarly may be misleadingly benign and therefore not alert the surgeon to a serious underlying condition. Among patients hospitalized to an intensive care unit; altered mental status, absence of peritoneal signs, analgesics, antibiotics, and mechanical ventilation all contribute to delays and difficulties in surgical evaluation and treatment. All of these factors contribute to increased rates of morbidity and mortality among the elderly with surgical emergency conditions [30, 31].

12.4.2 Frailty and Emergency General Surgery

During the past few decades, quality of health care has become an important focus of outcomes research. The objective of such research is to bring to light best evidence-based practices that help improve patient outcomes. Countless studies have examined outcomes after general surgery in older adults. Predominantly, these studies have looked at mortality and complications as outcomes. The association of age and adverse outcomes is well established and validated. However, more recently the focus has shifted from age to functional status as a predictor of postoperative outcomes in patients undergoing general surgery. The use of objective measures of preoperative assessment helps in informed decision making, which is crucial for geriatric patients undergoing emergency general surgery and their families. The American College of Surgeons (ACS) has developed a surgical risk calculator based on multi-institutional NSQIP data that allows to accurately estimate the risk of most common surgical procedures and will help in informed decision making [32]. This risk calculator is based on 21 preoperative risk variables and also allows to adjust for surgeon’s estimation of an increased risk using the Surgeon Adjustment Score (SAS) . Several studies have shown that the NSQIP calculator reliably predicts the postoperative complication risk of surgical patients and aids clinicians and patients to make decisions using empirically derived patient-specific postoperative risks [33]. While accurate, the ACS NSQIP calculator does not incorporate several components of frailty that contribute significantly to the final postoperative outcomes of surgical patients. Studies have also shown that for patients undergoing emergency general surgery, frailty index better predicts complications and the addition of these additional variables to the NSQIP calculator may significantly improve the predictability of the NSQIP calculator [34].

Several models exist for the calculation of frailty index. The most comprehensive frailty questionnaire is the Rockwood frailty model based on 70 variables that assess the cognitive, physiological, physical, and social wellbeing of the individual. The Rockwood frailty index has been validated in patients undergoing an elective surgery. More recently a modified 50-variable Rockwood frailty index has been shown to reliably predict morbidity in patients undergoing emergency general surgery [35]. Interestingly, using the 15 strongest predictors out of the 50 variables, a similar predictability can be achieved. The use of this 15-variable EGS-specific frailty index allows for a more rapid yet accurate assessment of frailty status of patients undergoing emergency general surgery (see Table 12.1). For each question in the frailty index, a patient receives a score varying from 0 to 1. The sum of final score is then divided by 15 to calculate the frailty index of the patients. Patients with a frailty index of >0.325 are considered frail and are at high risk for morbidity following emergency general surgery.

12.4.2.1 Key Points

Several risk assessment tools for geriatric patients undergoing emergency general surgery exist.

Preoperative risk assessment aids the clinicians and patients in informed decision making .

Frailty can be assessed in patients undergoing an emergency general surgery using a simple 15-variable EGS-specific frailty index.

12.4.3 Acute Diverticulitis

Diverticular disease is a common disorder in elderly resulting in 312,000 hospital admissions and 1.5 million days of inpatient care every year in the USA [36]. Over 75 % of patients above 70 years of age in the western countries have colonic diverticulosis with left hemicolon being the most common site (sigmoid diverticulosis 95 %) [37]. As individuals age, a variety of physiologic alterations manifest, many of which affect structural components of the colon, intraluminal pressure, colonic motility, and electrophysiology [38].

12.4.3.1 Age-Related Changes

Structural components of the extracellular matrix of the colonic wall are important in maintaining the strength and integrity of the colonic wall. Age-related changes take place in these components such as damage and breakdown of mature collagen and replacement with immature collagen. These changes decrease the compliance, leading to a stiffer tissue that is more vulnerable to tears especially under conditions of increased luminal pressures [39]. Age-related neural degeneration can lead to reduction of neurons in the mesenteric plexus and the intestinal cells of Cajal (the so called intestinal pacemaker cells ), which induces smooth muscle dysfunction. Age-related functional changes in the colon such as increased uncoordinated motor activity and high amplitude propagated tonic and rhythmic contractions result in segmentation, which significantly increases colonic intraluminal pressure. The pathogenesis of diverticulosis has also been associated with lack the dietary fiber. Other risk factors associated with diverticulosis are obesity, smoking, NSAID, and aspirin.

Up to 80 % of diverticulosis patients are asymptomatic. Other symptoms vary from mild to severe fecal peritonitis with septic shock. In mild cases, patients present with lower abdominal pain and tenderness most commonly localized to the left side with loose stool or constipation. Elderly patients with intra-abdominal sepsis tend to present to physicians with less acute and delayed symptoms compared to younger patients. The classic triad of acute diverticulitis is lower abdominal pain, fever, and leukocytosis; however, this triad is only seen in less than half of cases. It is important to note that only 50 % of elderly patients with intra-abdominal infection will present with nausea, vomiting, and fever. Cutaneous and visceral pain sensitivity decreases with age which can explain why elderly patients with abdominal sepsis present with a benign abdomen. The absence of definitive findings such as guarding and rigidity can decrease a physician’s alertness to the presence of intra-abdominal sepsis. Thus, it is important that physicians maintain a high level of suspicion during physical examination of elderly patients [40].

The gold standard imaging test for the diagnosis of acute diverticulitis is computed tomographic (CT) scan which has a high sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis of acute diverticulitis [41, 42]. The use of colonoscopy and sigmoidoscopy should be avoided in the acute stage of the disease as it may lead to perforation of the inflamed bowel. Colonoscopy is usually recommended 4–6 weeks after the acute phase of the inflammation to rule out other coexisting diseases such as cancer.

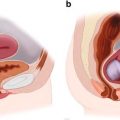

Conservative management for acute uncomplicated diverticulitis is successful in 70–100 % of cases [43]. Geriatric patients with acute diverticulitis can be managed safely with outpatient therapy. For these patients the treatment of choice is 7–10 days of oral broad spectrum antibiotics [44]. Hospitalization is indicated only in patients that require analgesia, are unable to tolerate any diet, or in cases of complicated diverticulitis . The patient should be made NPO and broad spectrum antibiotics should be administered intravenously. These patients are followed serially with white cell counts, abdominal examination, and repeat CT scans (Fig. 12.1).

Fig. 12.1

Management of acute diverticulitis

12.4.3.2 Key Points

Several anatomical and physiological changes in the colon associated with advancing age predispose the elderly to diverticular disease.

The presentation of acute diverticulitis in the elderly is subtle compared to the younger counterparts.

Medical management with bowel rest, analgesics, and antibiotics remain the corner stone treatment of acute diverticulitis.

12.4.4 Mesenteric Ischemia

Mesenteric ischemia is a rare but relatively common disorder in the elderly [45]. Despite the recent improvement in diagnosis and treatment, it is still associated with significant mortality rates around 60 % [46]. Approximately 50 % of elderly patients have a degree of atherosclerosis of the celiac, superior, and inferior mesenteric arteries which can precipitate acute mesenteric ischemia [47]. The superior mesenteric artery is most commonly implicated in acute mesenteric ischemia. Arterial embolism, arterial and venous thrombosis, and non-occlusive ischemia are the main causes of acute mesenteric ischemia [47]. Typically acute mesenteric ischemia presents with poorly localized severe abdominal pain classically described as “pain out of proportion” due to the absence of associated findings on physical examination [48]. The presence of these clinical features with preexisting comorbidities such as atrial fibrillation, ischemic heart disease, and atherosclerosis should increase physicians’ suspicion to consider mesenteric ischemia as a potential diagnosis. Of elderly patients, 30 % will present with nonspecific symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, or diarrhea that can mislead the diagnosis of mesenteric ischemia to a more benign disorder like gastroenteritis [48]. Ultimately, patients develop distention, shock, abdominal tenderness with guarding, and perforation [49]. Leukocytosis with a white blood cell count greater than 15,000/μ is present in only 75 % of the patients. Metabolic acidosis and elevated serum lactate and amylase may be present if infarction has occurred. Fecal occult blood is reported in 50–75 % of the patients. Gross bleeding, however, occurs on rare occasions. As there is no definitive lab test and usually physical examination reveals nonspecific findings, physicians should maintain a high level of suspicion [50]. Plain X-rays films may initially be unremarkable but they may demonstrate intestinal distention and air-fluid levels. According to recent studies, CT angiography has a sensitivity of 80 % for diagnosing acute mesenteric infarction. Findings on CT scan indicative of mesenteric ischemia include thromboembolism in mesenteric vessels, portal venous gas, pneumatosis, diffuse bowel wall thickening, and mesenteric edema. Selective mesenteric angiography has a sensitivity of 90–100 % and is recommended if mesenteric ischemia is strongly suspected. However, due to the high prevalence of renal atherosclerosis in elderly, angiography can result in renal toxicity and should be kept in mind [47, 48].

12.4.4.1 Key Points

Vague nonspecific clinical signs in geriatric patients can be deceiving.

Comorbidities have a strong association with acute mesenteric ischemia.

Early diagnosis and treatment of mesenteric ischemia in the elderly is crucial.

12.4.5 Acute Cholecystitis

Biliary tract disease including cholecystitis is the most common indication for abdominal surgery among elderly with abdominal pain [51]. The prevalence of gallstones increases sharply with age. About 15 % percent of men and 24 % of women have gallstones by the age 70. By age 90, this increases to 24 and 35 %, respectively [52]. Gallbladder disease in the elderly tends to be more severe compared to their younger counterparts as evidenced by the fact that a higher proportion of elderly patients undergo cholecystectomy for acute causes rather than elective cholecystectomy [53]. Biliary tract disease in the elderly is further complicated by the greater incidence of common bile duct stones. Common bile duct stones are found in patients undergoing cholecystectomy in up to 30 % of those in their 60s and in up to 50 % of those in their 70s [54]. Age-related changes in the biliary tract such as decrease bile salt secretion, increased cholesterol precipitation of the bile, increased common bile duct diameter, and decrease in gall bladder contractility are thought to account for the increased incidence of gallstone disease [55–57].

Acute cholecystitis presents a unique set of challenges in the elderly population. The typical presentation of acute cholecystitis includes severe right upper quadrant or epigastric pain, fever, nausea, and vomiting [53]. Laboratory values usually reveal leukocytosis with an increased number of band forms and may demonstrate a mild rise in transaminases, bilirubin, and alkaline phosphatase [58]. Diagnosis of acute cholecystitis in the elderly can be challenging as they commonly have a delayed and atypical clinical presentation. Abdominal pain remains a common presenting symptom but nausea, vomiting, fever, or leukocytosis is often absent. Symptoms are usually misleading and the clinical presentation is often blunted because of age-related physiological changes, mental illness, cognitive disability, dementia, or associated medications [59]. Around 40 % of elderly patients presenting with acute cholecystitis do not develop fever and more than 50 % may have negative peritoneal signs on examination. Absence of these signs does not indicate milder form of the disease as 40 % of the patients have severe complications [60]. The estimated diagnostic accuracy of clinical examination in acute abdominal pain in patients over the age of 80 is only 29 %, which is significantly low compared to younger patients [61]. Approximately 12 % of elderly patients with acute cholecystitis present in septic shock [62]. Surgical risks and complications of acute cholecystitis occur in more than 50 % of all patients older than 65 years. Complications include acute ascending cholangitis, gallbladder perforation, emphysematous cholecystitis, biliary peritonitis, carcinomatous changes, and gallstone ileus [63]. Acute ascending cholangitis is a disease of the elderly and rarely occurs before the age of 40. Most patients with acute ascending cholangitis present with Charcot’s triad (i.e., fever, jaundice, and right upper quadrant pain) and occasionally as Reynold’s pentad (i.e., Charcot’s triad plus shock and mental status changes) [64].

Liver function tests remain the most important laboratory investigation in patients with suspected gall bladder disease. Patients with acute cholecystitis can present with a mild elevation in serum ALT and AST levels, however, the most significant abnormal laboratory values include the levels of bilirubin (total and fractionated) and alkaline phosphatase (AP). Ultrasound is the diagnostic gold standard for the diagnosis of acute cholecystitis.

Asymptomatic gallstones are a common feature in the elderly. Most patients with gallstones never develop acute cholecystitis. Among patients who experience a single episode of biliary colic, nearly half will never experience a second episode of colic within 5 years [65]. Based on these facts, conservative management of biliary colic may be considered appropriate for most elderly patients. Differentiating biliary colic from acute cholecystitis can be challenging in the elderly patients with diabetes mellitus. The presentation of acute cholecystitis in elderly patient with diabetes associated neuropathy is minimal. In such patients gangrenous cholecystitis can present with minimal symptoms and negative peritoneal signs can be misinterpreted as a recurrent attack of biliary colic [59]. Therefore, a very low threshold for suspicion should be maintained for these patients.

The gold standard for the management of acute cholecystitis is laparoscopic cholecystectomy. The rate of emergent cholecystectomy in patients older than age 65 is 37.6 % compared to 3.3 % in younger patients [66]. Postoperative morbidity, particularly cardiovascular and pulmonary complications, is significantly greater after emergent cholecystectomy compared to elective cholecystectomy in elderly patients [53]. For patients who are non-operative candidates or who cannot tolerate anesthesia in emergent settings, non-operative management with and antibiotics has shown to be effective.

12.4.5.1 Key Points

The presentation of gall bladder disease in the elderly is extremely subtle compared to the younger counterparts.

Early laparoscopic cholecystectomy is the gold standard treatment for acute cholecystitis across all age groups

Biliary tract decompression with cholecystostomy and antibiotics has shown to be effective in non-operative candidates with acute cholecystitis.

12.4.6 Acute Appendicitis

Acute appendicitis is the most common emergent abdominal surgery performed with a lifetime incidence of 7 % [67]. Generally, appendicitis is considered to be a disease of the young with only 5–10 % of cases occurring in the elderly population. However, the incidence of the disease in the elderly is increasing due to an increase in the elderly population. Acute appendicitis is the third most common cause of abdominal pain in elderly [18]. The pathophysiology of appendicitis in the elderly is similar to the young however, there are several differences in the elderly that predispose them to increased progression and early perforation. The lumen of the appendix is narrowed and atherosclerosis compromises the blood flow to the appendix [68, 69]. As a result even mild increases in intraluminal pressure can lead to gangrene and perforation [67]. The reported incidence of perforation in elderly patients with acute appendicitis is as high as 70 % [70]. The blunted inflammatory response in the elderly prevents the development of significant clinical features of acute appendicitis and delays the presentation. This delay is further complicated by the delay in the time from presentation to the operating room and is associated with increased morbidity and perforation rates [71–73]. The diagnosis of acute appendicitis in the elderly is often delayed due to other suspected etiologies. Age-related physiological changes, atypical presentation, and a delay in seeking medical help lead to the delay in diagnosis and treatment. Due to these reasons, acute appendicitis is the leading cause of intra-abdominal abscess and fever of unknown origin in elderly. The prognosis of uncomplicated appendicitis in both the young and old age groups is equal, however, when perforated appendicitis occurs the elderly have a mortality rate of 33–50 % [67].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree