Fig. 15.1

Careful surgical positioning of the elderly patient is essential. (a) A patient with an ankle fracture is positioned with padding and safety straps. (b) Ecchymotic skin is frequently encountered in the elderly patient. Such skin must be handled gently

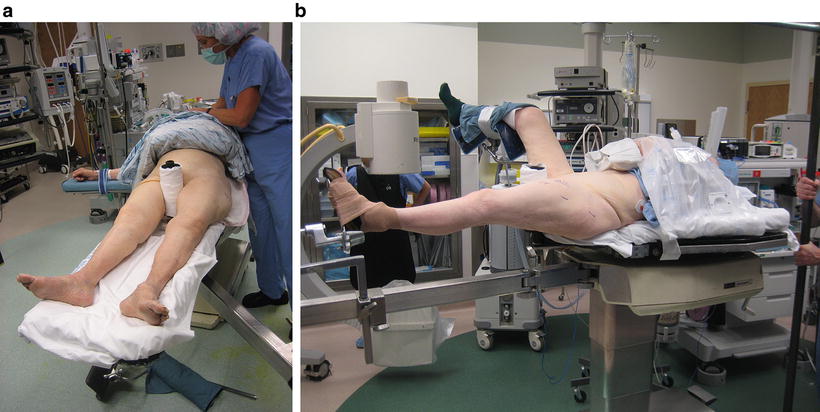

Fig. 15.2

(a) A patient is positioned on the fracture table with padding of bony prominences. (b) A warm air blanket keeps the patient’s core body warm during surgery

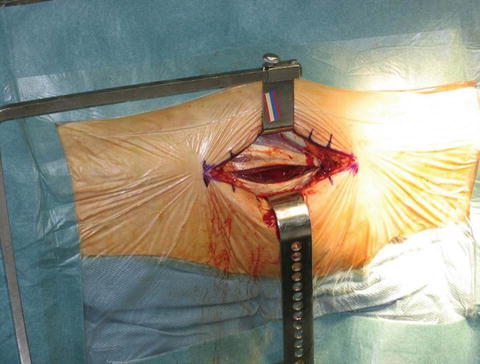

Positioning should be done with the help of the attending physician to be certain that appropriate exposure is achieved and that the patient rests in a comfortable position during surgery. The drapes should be securely fixed to the patient, preferably with adhesive rather than staples or towel clamps (Fig. 15.3). Care in removing drapes is essential to avoid injury especially to age related skin atrophy; for example, circular bandages should be unrolled to avoid injury as is more likely if cut.

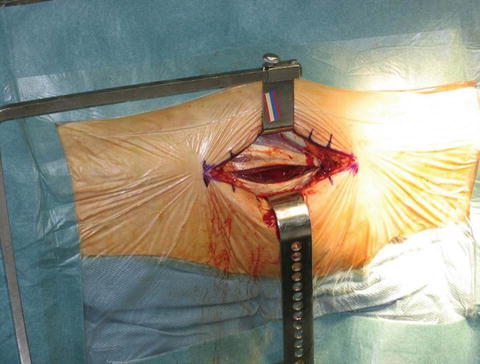

Fig. 15.3

Surgical draping with iodine impregnated sticky drapes

Shorter surgical time reduces the risk of wound infection, blood loss (Fig. 15.4), untoward effects of the anesthetic, and likely cognitive dysfunction (Fig. 15.5). Proper fluid management is vital to reduce complications [50–53].

Fig. 15.4

Meticulous attention to hemostasis is suggested in elderly patients to help them remain in a state of medical equilibrium

Fig. 15.5

A periprosthetic fracture occurred intraoperative in this 85-year-old patient

Clinical assessment of the patient’s volume and hemoglobin status is essential in every patient. Fluid depletion is best corrected with isotonic saline with caution to avoid over expansion. The NIH-sponsored FOCUS trial, Safety and Effectiveness of Two Blood Transfusion Strategies in Surgical Patients with Cardiovascular Disease, suggests maintaining hemoglobin levels at or above 8 g/dL for elderly patients with cardiac comorbidities [54].

Because of poor bone quality arthroplasty is valuable and a variety of cemented implants should be available.

Hip fracture, femur fracture, and periprosthetic fracture should be performed urgently for reasons noted earlier. Proximal humerus fracture and distal radius fracture surgery can be semi-elective. A detailed care pathway discussed early is able to improve outcome quality, patient satisfaction, and lower costs [3, 4, 17, 22].

15.15 Postoperative Care

Postoperative care should be standardized and protocol driven and ideally involving an interprofessional team.

Pain management is complex: under-reporting, especially in those with cognitive impairment, and analgesics have an increased side-effect profile in older people. Multimodal analgesia using narcotics, non-narcotic analgesics, and local nerve blocks is effective [55–58]. The combination of NSAIDs/acetaminophen with opiates produces synergistic pain relief and decreases the need for opioid medications. Intravenous, oral and subcutaneous morphine, fentanyl, and hydromorphone have no difference in the deterioration of cognitive function or incident delirium [57]. Meperidine causes delirium and should be avoided [58].

Intravenous patient-controlled analgesia (PCA ) provides superior postoperative pain relief compared to nurse administered boluses but because of comorbidities, especially brain disease and hand arthritis it may not be effective in some seniors.

Meta-analyses found that local nerve blocks are effective and reduce complications in femur fracture [59, 60].

In most situations, the goal of orthopedic surgical intervention is to restore the patient to their prior level of activity and independence, or to an increased level of independence. A secondary goal of surgery is to prevent the complications of immobility and its sequelae—pressure sores, stiff joints, deconditioning, pneumonia, and delirium. In almost all cases, rehabilitation should begin soon after surgery. Every surgeon has his or her own preference in the initiation of mobility and physical therapy and these differences depend on the surgery performed (a patient with total knee arthroplasty may immediately bear weight as tolerated while one with a tibial plateau fracture may be non-weight bearing for some time). The surgeon must decide on this status, and engaging early physical and occupational therapists is most valuable to achieve the best outcomes, avoid complications, and achieve ideal analgesia [61–63].

Braces are best avoided but occasionally one is essential: tibial plateau fracture, some ankle fractures, and minor wrist fractures management. Complications of braces include delirium, pressure pain, tendon injury, and skin breakdown.

Orthopedic patients are especially vulnerable to skin injury. Pressure sores are serious complications and can lead to hospital readmission, sepsis, surgery, and death. With high quality care they are largely preventable. Doing so lies in careful bedside care. Skin must be checked several times a day for proper positioning, padding, redness, blisters, and ulcers. Sores most commonly are found at the hips, sacral region, heels, and elbows. Routine and frequent skin assessment and care by members of the multi- or interdisciplinary team is most valuable in avoiding or managing skin pressure problems. Such an approach is better than the common practice of the past, which included routine repositioning (an activity that can cause a shear injury, a precursor to an ulcer), pressure relieving mattresses or beds. Interdisciplinary team care and early mobilizations are effective strategies in reducing skin injury [64–67].

Evaluation tools for assessing risk of pressure ulcers include the Braden [68] and Norton [69] scales. The Norton scale may be better at identifying high-risk patients [69]. Grip strength (possibly as a surrogate for sarcopenia) predicts inpatient and 30-day risk of pressure ulcers [70].

Delirium is a common and serious complication in the postoperative affecting about half of patients after hip fracture and increasing mortality and length of stay [4, 71–74]. Certain medications sometimes used perioperatively (anticholinergics, benzodiazepines, skeletal muscle relaxants, and NSAIDs) are important precipitants and are best avoided. Other risk factors and strategies to minimize this complication are discussed in depth in Chap. 2.

Falls in the elderly are often multifactorial. Reducing the risk of a future fall is of utmost importance. A home safety evaluation should be considered when necessary, and proper modifications implemented (Fig. 15.6).

Fig. 15.6

Tripping hazards are present on these stairs: items such as shoes on the stairs, and slick stair treads

With the increasing popularity of bisphosphonates , atypical bisphosphonate-related femur fractures have become more common (Fig. 15.7). For patients undergoing osteoporosis treatment with this class of medication, it is important to determine the risk of fracture of the contralateral side in the postoperative period.

Fig. 15.7

A stage 1 atypical fracture on the lateral cortex of the femur was a result of excessive duration of bisphosphonate therapy

The risk of complications, poor outcomes, and mortality in older orthopedic patients requiring surgery is high, a result of many comorbidities, losses of physiological function and remarkable heterogeneity. Such patients are simply more vulnerable, and perioperative care requires a highly orchestrated interdisciplinary team to achieve the best outcomes [75–85].

References

1.

Cram P, Lu X, Kates SL, Singh JA, Li Y, Wolf BR. Total knee arthroplasty volume, utilization, and outcomes among Medicare beneficiaries, 1991–2010. JAMA. 2012;308(12):1227–36.PubMedPubMedCentral

2.

Cutler DM, Ghosh K. The potential for cost savings through bundled episode payments. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(12):1075–7.PubMedPubMedCentral

3.

Batsis JA, Phy MP, Melton 3rd LJ, Schleck CD, Larson DR, Huddleston PM, et al. Effects of a hospitalist care model on mortality of elderly patients with hip fractures. J Hosp Med. 2007;2(4):219–25.PubMed

4.

Friedman SM, Mendelson DA, Bingham KW, Kates SL. Impact of a comanaged Geriatric Fracture Center on short-term hip fracture outcomes. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(18):1712–7.PubMed

5.

McNeil CK, K and r, M. Talking with your older patient – a clinician’s handbook 208 [cited 2015 October 13, 2015]; 1: Available from: file:///C:/Users/Steve/Downloads/talking_with_your_older_patient.pdf.

6.

Grigoryan KV, Javedan H, Rudolph JL. Orthogeriatric care models and outcomes in hip fracture patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Orthop Trauma. 2014;28(3):e49–55.PubMedPubMedCentral

7.

Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, Newman AB, Hirsch C, Gottdiener J, et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56(3):M146–56.PubMed

8.

Makary MA, Segev DL, Pronovost PJ, Syin D, Bandeen-Roche K, Patel P, et al. Frailty as a predictor of surgical outcomes in older patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;210(6):901–8.PubMed

9.

Farhat JS, Velanovich V, Falvo AJ, Horst HM, Swartz A, Patton Jr JH, et al. Are the frail destined to fail? Frailty index as predictor of surgical morbidity and mortality in the elderly. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;72(6):1526–30. discussion 30-1.PubMed

10.

Pioli G, Barone A, Giusti A, Oliveri M, Pizzonia M, Razzano M, et al. Predictors of mortality after hip fracture: results from 1-year follow-up. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2006;18(5):381–7.PubMed

11.

Bell JJ, Bauer JD, Capra S, Pulle RC. Quick and easy is not without cost: implications of poorly performing nutrition screening tools in hip fracture. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62(2):237–43.PubMed

12.

Fiatarone Singh MA. Exercise, nutrition and managing hip fracture in older persons. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2014;17(1):12–24.PubMed

13.

Gumieiro DN, Rafacho BP, Goncalves AF, Tanni SE, Azevedo PS, Sakane DT, et al. Mini Nutritional Assessment predicts gait status and mortality 6 months after hip fracture. Br J Nutr. 2013;109(9):1657–61.PubMed

14.

Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–83.PubMed

15.

Poses RM, McClish DK, Smith WR, Bekes C, Scott WE. Prediction of survival of critically ill patients by admission comorbidity. J Clin Epidemiol. 1996;49(7):743–7.PubMed

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree