Introduction

Europe has a landmass of 9 938 000 km2, 6.7% of the total land area on earth. Unlike the United States of America, Europe is not a federation of states with a unifying governmental structure, but a continent that groups 49 very diverse countries, with long and diverse history, languages, climates, customs, traditions, cultures, populations and governments. However, in the last century the European Union (EU) has provided a certain amount of integration between the member states in terms of laws, trade and governmental policies. At present, the EU has expanded to 27 member states, and a number of other countries have applied to become members. In 2010, the EU had 499 million inhabitants—the world’s third largest population after China and India—and includes many of the countries with the world’s highest proportions of older people.

The EU developed after World War II, with the aim of ending the frequent and bloody wars between neighbours, and has been growing in number of countries and depth of understanding ever since. EU citizens have freedom of movement of goods, services, people and money within their countries. Passports are not needed to move within most countries, and many share now a common currency, the Euro. The EU brings many unifying initiatives, but countries have the right not to join many multilateral EU initiatives, which helps to explain the present heterogeneity of the Union. Active debate is ongoing on the need for a European constitution.

The EU is not a traditional federation of countries, neither is it a common organization for cooperation between governments, like the United Nations. Member states of the EU remain independent nations but they delegate some of their decision-making powers to shared institutions, so that decisions on specific matters of joint interest can be made democratically at European level. The EU has a complex structure, where three main institutions participate in decision-making. The Council of the European Union, which represents the individual member states, is the main decision-making body, where ministers from each member state can commit their government to various EU policies. The European Parliament represents the EU’s citizens, its members being elected directly by voters in each state. The European Commission, based in Brussels, Belgium, is the civil service of Europe, and is independent of national governments. Its job is to represent and uphold the interests of the EU as a whole. It is split into various directorates which each have an appointed political head combined with an overall Commission President. The Commission has responsibility for proposing European legislation (the Parliament and Council decide on adoption of new laws), implementing agreed policy (together with national governments), enforcing EU law and representing the EU at international level.

Healthcare is not included in the list of common policy areas; only public health is, and this has a critical impact on the provision of healthcare and the organization of healthcare systems around Europe. Each EU country is free to decide on the health policies best suited to national circumstances and traditions, although they all share common values. These include the right of every citizen to the same high standards of health and equity in access to quality healthcare. The EU is also committed to taking into account the implications of health in all its policies and decisions.

Demography

The EU compiles statistics from member states through its agency Eurostat (epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu), including a great wealth of population- and health-related parameters. However, Eurostat does not collect data directly, but rather collates and tries to harmonize data obtained from national agencies, so problems may arise with the uniformity of their collection, not only in terms of completeness but also their comparability and quality. Most relevant statistical data are open access and regularly updated.

Bearing in mind the above, it appears that Europe’s population has been ageing steadily for a long time. The total EU population is projected to rise by 5% between 2008 and 2030, and the median age is likely to increase in all but seven out of the 281 European regions, due to the combined effect of three factors: the existing population structure, fertility lower than replacement levels, and steadily rising numbers of people living longer.1 The proportion of the total population aged 65 or over is projected to increase considerably in the near future, from 17.1% in 2008 (87 million) to 23.5% (123 million) in 2030. The number of very old, aged >80 years, is already 22 million (4.4% of the population), and in 11 of the former EU-15 member states, at least 10% of their population will be aged 80 or over by 2050. Gender differences in ageing are considerable, as life expectancy for women is currently more than six years longer than for men.

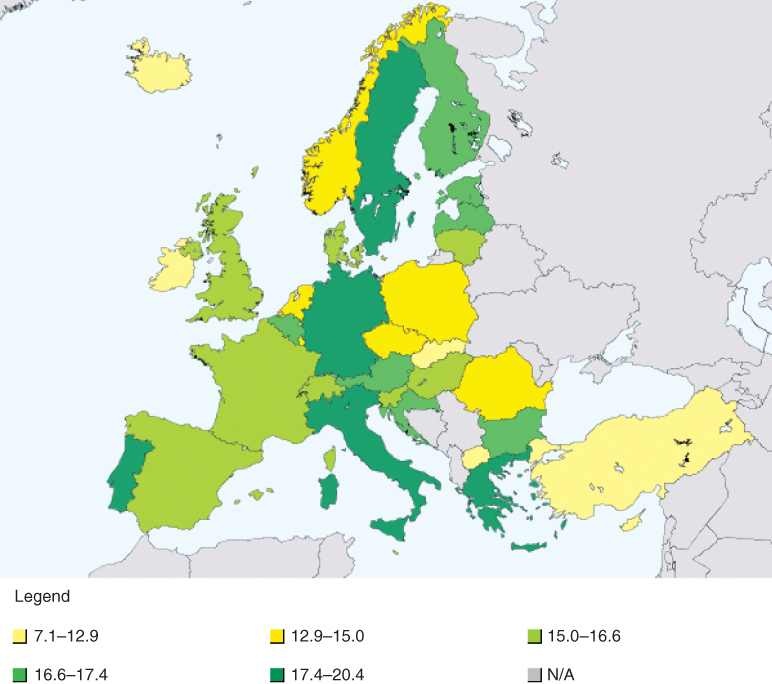

These global figures may disguise major variations across the EU countries, both in population growth and in ageing rates. Life expectancy at birth varied in males in 2007 from 64.9 years in Lithuania to 78.9 years in Sweden, and in females from 76.1 years in Romania to 84.4 years in France. The share of the population aged 65 years or over in the 27 EU countries ranged in 2008 between 10.9% in Ireland and 20.1% in Germany (Figure 148.1). Regional variation is even higher, ranging between 9.1% (in Inner London, UK) and 26.8% (in Liguria, Italy). Contrary to expectations, these differences are not diminishing, but are expected to increase in the near future, ranging in 2030 between 10.4% (again in Inner London, UK) and 37.3% (in Chemniz, Germany). The proportion of citizens >80 years in 2008 ranged between 2.7% in Ireland and 5.5% in Italy.

In parallel with these changes, the working population over the same time frame is projected to decrease significantly. The old age dependency ratio, defined as the projected number of persons aged 65 and over expressed as a percentage of the projected number of persons aged between 15 and 64, is projected to increase from 25.9 in 2010 to 38.0 in 2030. This has been called a ‘demographic time bomb’ and has considerable implications for health and social care planning across the EU.

Major differences between EU member states also exist in active life expectancy (life expectancy with no disability). As a whole, in 2007 men in the EU were expected to live 80.9% of their life without disability, but this ranges from 89.3% in Norway to 71.9% in Germany. Women in the EU could expect to live 75.8% of their lives free of disability, ranging from 87.3% in Malta to 66.2% in Slovakia. Since 2003, the measurement of Healthy Life Years is considered a structural indicator on health in the EU, which is a very relevant step forward for geriatric prevention and care planning.

Healthcare and Health Systems

Medicine has developed in Europe for more than 25 centuries: Hippocrates of Kos (Greece) is considered to be the father of modern medicine, and over the centuries many milestone advances have been made in European countries. There is a centuries-old tradition of medical care, and all the EU member states have systems in place that offer complete, or near complete, rights to healthcare for people residing within their borders. High-quality health services are considered a priority issue for European citizens, and rights to healthcare are recognized in the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the EU. Most countries jealously guard management of their own healthcare systems, so it is no surprise that, with the exception of public health, states retain competence for health policies and health systems, and do not delegate these under EU instances. However, and very recently, health systems policies across the EU countries seem to be more interconnected, due to public expectations, movement of patients and health professionals across countries, and information and medical technology. The EU holds responsibility to complement the work of member states (i.e. in patient mobility or international health threats) and to reduce health inequalities, fostering cooperation between countries.

Healthcare systems in the EU are financed in two broad ways, either through general taxation, or using systems based on social health insurance, although in highly variable proportions. Taxation predominates in some countries (e.g. Denmark, Italy, Spain, Sweden and the United Kingdom), while social health insurance contributions are the predominant source in others (e.g. the Czech Republic, France, Germany and the Netherlands).2 Both systems usually limit their liability to pay the full cost of treatments, such that expenditure borne by households amounts to 20–30% in the majority of member states. The difference is made up either through direct contributions or via supplementary private insurance. It is, however, clear that public-sector funding makes up a significant proportion of health expenditure in all the EU member states: this proportion being lowest in Greece (56%) and rising to a high 95% in the Netherlands.

Although in most states universal access to healthcare is granted, including for older, impoverished or immigrant populations, the reliance on a degree of financial participation may adversely affect some groups’ access to healthcare as they are unable to afford the costs. This is particularly true of older people who may have both lowered incomes and considerable comorbidity. Thus some member states have enacted methods to target older people either by reducing their financial liability or ensuring that they are regularly screened by relevant health professionals. However, the universal access approach is putting a great deal of financial pressure on the sustainability of the whole care system.

The impact of ageing on health and long-term care systems is considered to be one of the most significant challenges for the economies and welfare systems of European countries. According to OECD Health Data 2010, total health expenditure in EU countries in 2008 ranged from 6.1% of gross domestic product in Estonia to 11.2% in France. This contrasts with 16% in the same period in the United States. As most experts predict that increases in healthcare expenditures will continue over the next 50 years, finance is a major issue for most countries. Thus, the economic and financial affairs directorate is carefully examining this currently, estimating and modelling the size and timing of projected changes in expenditure and their underlying driving factors, in order to assess sustainability. Many publications have appeared recently feeding a public policy debate which may force changes in the near future.3

Health and Ageing Trends

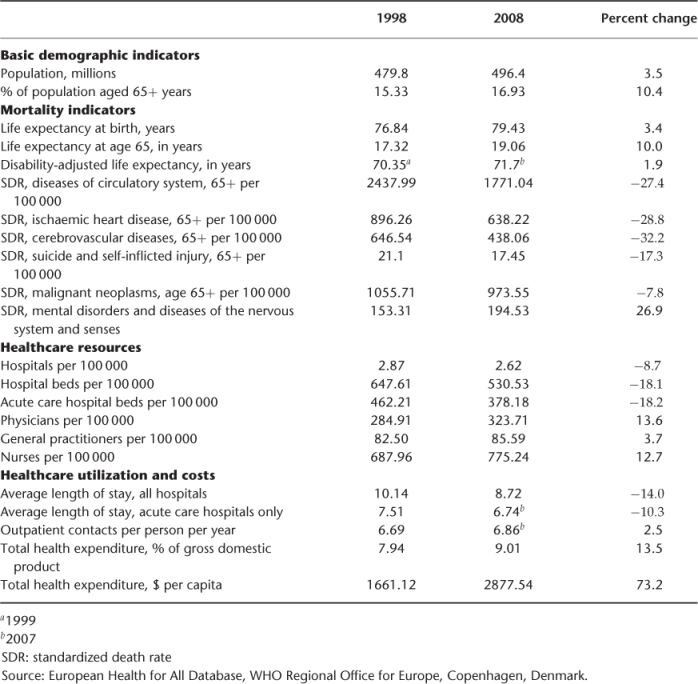

Life expectancy has been steadily growing in the EU over the last century, and this trend has not stopped in recent years (Table 148.1). A European citizen aged 65 years may expect to live more than 19 years into ‘old age’. This could theoretically mean that diseases and disabilities of old age are steadily increasing, although this is actually challenged.4 Changes in lifestyles, risk factor management, public health and healthcare have pushed for a slow but steady reduction in some of the main causes of mortality in old people, such as diseases of the circulatory system (a 27.4% reduction in the last 10 years), stroke (32.2% reduction) or cancer (7.8% reduction). However, mental health disorders (particularly dementing diseases and depression) seem to be increasing rapidly during the same time period (an increase of 26.7%), not only in mortality but especially in morbidity.

Table 148.1 Health trends in European Union member states in the last 10 years.

An enormous variability is also found in the health needs of individual countries within the EU, and differences have increased with the new countries that have recently joined. For instance, the standardized death rate by 100 000 inhabitants for ischaemic heart disease in 2008 ranges from only 33.8 in France to 321.3 in Lithuania, and crude death rates by 100 000 inhabitants from suicide in those aged 85 and over range from 1.9 in Ireland to 64.8 in Hungary in the same year. Thus, health planning in each country needs to take account of these differences, providing health promotion and care systems that are more prone to have an impact on relevant health outcomes in each country.

One of the main problems researchers in geriatric care are faced with when studying illness in older people in the EU is the lack of good morbidity data of geriatric interest. Health statistics are available for communicable diseases, for some chronic diseases, for health habits and lifestyles, and for disease related mortality. However, there are no reliable data regarding geriatric diseases and syndromes (delirium, hip fracture, urinary incontinence), nor in disease related physical and mental disability. Data are fragmented, come from different years and sources, are gathered with different criteria and are not systematically collected. Good age-specific data for older subjects are especially sparse. Research and progress in this area is urgently needed, and several research initiatives funded by the EU are trying to fill this gap.

For instance, research in health and social implications of ageing has been fostered through the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE, www.share-project.org

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree