Introduction

The Elderly Population in China

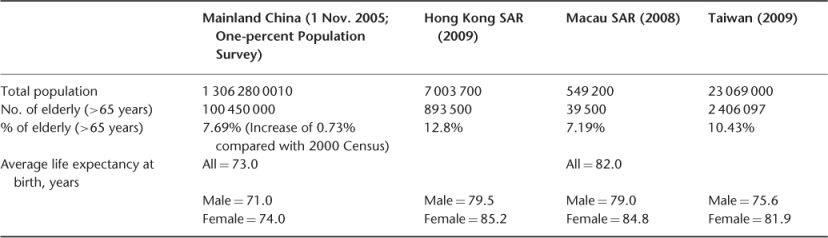

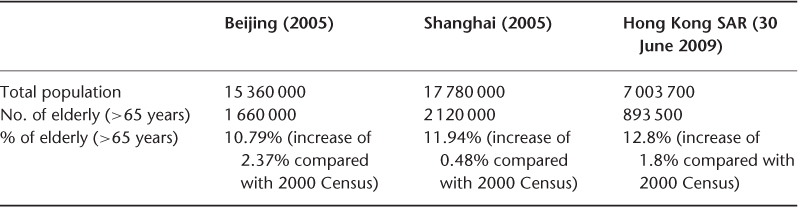

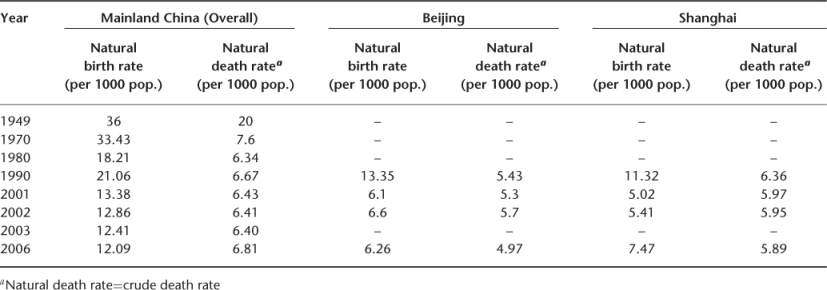

China is a developing country. It has undergone a rapid economic growth recently, and is now the world’s third-largest economy. In the past 60 years, China has made great achievements in controlling infectious diseases and improving public health. A direct indicator is the demographic transition from a young population into an ageing population. In 1999, the proportion of elderly people aged 60 years and over was already more than 10%. In the 5th National Population Census of 31 provinces, autonomous regions and municipalities of mainland China in November 2000, the population was 1 265 830 0010. There were 88 110 000 persons aged >65 years. This represented 7% of the population.1 In the 2005 One-percent Population Survey, the total population of China was 1 306 280 0010. The number of persons >65 years had increased to 100 450 000, which constituted 7.7% of the whole population. In 2005, average life expectancy at birth was 71.0 years for males and 74.0 years for females. (Tables 146.1, 146.2 and 146.3).2

Table 146.1 China’s population (including Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan).

Table 146.2 China major cities’ population in 2005, Hong Hong in 2009.

Table 146.3 Declining birth and death rates in mainland China.

There are several special features regarding population ageing in China. The number of elderly is huge and represents 20% of the world’s elderly population and 50% of the Asian elderly population, and the growth is rapid. From 1982 to 1999, the proportion of elderly persons aged >60 years increased from 7.64% to 10.1%. Such a demographic transition occurred within 18 years in China but the same change took several decades in developed Western countries. China has now moved into an accelerated phase of population ageing and is becoming an ageing society in an underdeveloped economy. While Western countries have become both ‘old’ and ‘rich’, China has become ‘old’ before getting ‘rich’. This constitutes a burden on economic growth. Another characteristic is the regional difference in the demographic transition. Population ageing occurs more rapidly in the developed coastal cities than in the underdeveloped inner rural areas within China. Urban cities show a higher proportion of elderly people than rural areas. For example, in 2005 Shanghai had the highest percentage of elderly people (11.94%) while Qinghai province had the lowest (6.04%).2 Amongst elderly population subgroups, the growth of those aged >80 years is fast and increasing at a rate of 5.4% per year. This subgroup increased from 8 million in 1990 to 11 million in 2000 and is projected to reach 27.8 million by 2020.1, 3 With an ageing population, the prevalence of chronic diseases, which include diabetes mellitus, hypertension, stroke, coronary heart disease and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, has also increased. For example, 1.5 million patients are newly diagnosed with stroke every year in China. Heavy medical expenses are required and these diseases constitute an important burden. Although the life expectancy of women is higher than men, women survive longer but are less healthy than men.1–6 The birth control and one-child policy has had a great impact on family size in China.7 The Chinese family has decreased from 4–5 to 3–4 person households in recent years. Family size is largest in rural areas and small in city areas. This trend has been affecting the foundation of traditional family support of the elderly population.

The Elderly Population in Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR and Taiwan

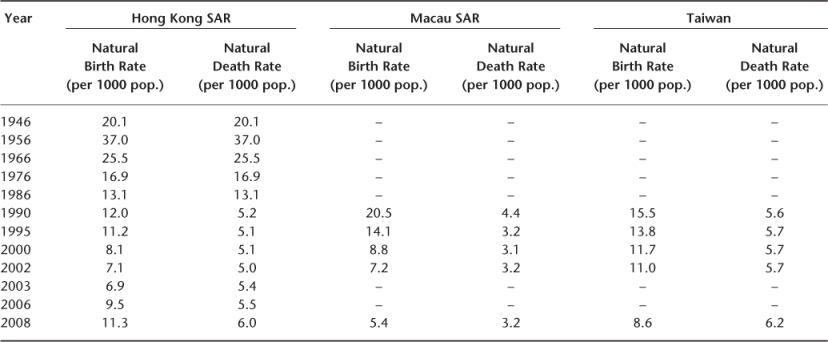

In 2009, 0.89 million persons in Hong Kong were aged 65 years and over, which represented 12.8% of the total Hong Kong population. The proportion of Hong Kong elderly will increase to 26.4% by 2036.8 This increase will place an enormous demand on long-term care and healthcare services. The ageing demographic change is related to a decrease in births in Hong Kong.9–12 The elderly dependency ratio, which is defined as the number of persons aged 65 years and over per 1000 persons aged 15–64 years, will increase from 382 in 2001 to 562 in 2031. In 2009, average life expectancy at birth was 79.5 years for men and 85.2 years for women (Tables 146.1, 146.2 and 146.4). Life expectancy is closely related to the healthcare needs of the elderly. In 2009, at age 60, the average life expectancy was 22.3 years for men and 26.9 years for women, and at age 80, this was 8.3 years and 10.6 years for men and women, respectively. The increased life expectancy is related to improvements in public health and nutrition, and also to improved medical care for very elderly patients.8–12 However, improved survival may not mean normal health without disability or functional impairment. Elderly persons have multiple chronic diseases, functional impairments and need for regular medical services.13–15

Table 146.4 Declining birth and death rates in Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR and Taiwan.

Macau SAR is a small city in China. In 2008, it had a population of 0.55 million. The natural birth and death rates have fallen over recent decades and the population is also ageing. In 2008, the elderly aged >65 years constituted 7.19% of its population. Average life expectancy at birth for males and females was 79.0 years and 84.8 years, respectively (Tables 146.1 and 146.4).16

Taiwan has also experienced a rapid demographic transition. The fertility rate has decreased from 5.9 children per woman in 1949 to 1.77 in 1997. Thus, the ratio of adult children to older parents will fall greatly in the coming years. A decline in the death rate has resulted in an increase in average life expectancy at birth. Between 1951 and 2008, average life expectancy at birth has increased from 53.4 years to 75.6 years for males, and from 56.3 years to 81.9 years for females. These changes have led to an increase in the elderly population (>65 years) from 2.5% in 1950 to 10.4% in 2008. This percentage is projected to increase to 24% by 2030. The increase of those aged 80 and over is very fast. In 1960, 9.2% of the elderly population belonged to the >80 group. By 2036, almost one-quarter (24%) of the elderly population will be in this group.17–19 (Tables 146.1 and 146.4).

Policies toward Ageing in Mainland China

Officially, the basic principle of China’s ageing policy is to maintain sustainable development by setting up a support system partnership involving the state, community, family and the individual. The priorities in meeting the challenge of population ageing in China are to develop China’s economy, to set up an old age security system, to speed up the establishment of a community-based care system, to set up a legislative system to protect the rights of the elderly (the Law of the People’s Republic of China on Protection of the Rights and Interests of the Elderly was enacted in 1996), to establish safety networks for the elderly, to raise their living standards, and to create an environment for healthy ageing. In the past decade, China has set up five guiding principles for the work on ageing. These are ‘Elderly people should be supported, have medical care, be contributive to society, be engaged in life-long learning and live a happy life’. In 1994, the China Development Outline on the Work of Ageing was formulated with a view to gradually upgrading living standards of the elderly and to enrich their cultural life.20

As formal care services are limited, many older persons rely on the support of family members, particularly in rural areas. Family support functions include financial support (income security), care-giving tasks (physical care) and comforting tasks (psychological care). Most of the younger population still maintain that taking care of elderly family members is their responsibility. However, more and more young people are unable to provide all of these functions, and require some assistance from the government, policy-makers and community services providers.4, 6

It is projected that the rapid ageing in China will lead to only 2 working-age people for every senior citizen by 2050, compared with 13 to 1 now. Pension support is of great concern. As of March 2008, the Chinese pension system covered 205 million people, which represents 15% of the population. In rural areas, the pension system started in 1990 and covers only about 10% of the rural labour force. A further one-third drop in the number of pension participants occurred between 1999 and 2004. This was a setback attributed to the government’s shortsightedness, as it was assumed that families would take care of rural elderly. Family support is declining, as younger family members migrate to work as labourers in factories, construction sites or other employment in cities. There is a plan to expand urban and rural pension coverage which aims at changing the present system to help migrant workers who change jobs frequently to maintain their retirement benefits.21 There are other initiatives, including four ‘demonstration bases’ in the cities of Beijing, Tianjin and Chongqing, and in Jiangsu Province. The total investment would amount to 500 million yuan (Chinese dollars) each year. These centres would provide a model for the industry on care for the elderly. With regard to public commitment to long-term care, there will be an increase in the number of nursing homes. For example, Beijing plans to add 15 100 nursing home beds in 2010, that is, an increase of 43%.21

Health of the Elderly in Mainland China and Hong Kong SAR

In mainland China in 2008, the top killer diseases included cancer, cerebrovascular diseases, respiratory diseases, heart diseases, injuries and poisoning. Chronic diseases included hypertension, cerebrovascular diseases and coronary heart disease (CHD). Diabetes mellitus and CHD are more common in urban city areas than in rural areas.22–25 (Table 146.5). All these fatal and chronic diseases occur predominantly in elderly persons.

Table 146.5 Causes of death and common chronic diseases in China (all ages), 2008.

| City | County |

Top killer diseases in 2008: Male 1. Cancer 2. Cerebrovascular diseases (stroke) 3. Heart diseases 4. Respiratory diseases 5. Injury and poisoning 6. Diseases of the digestive system 7. Endocrine, nutrition and metabolic diseases (e.g. diabetes mellitus (DM)) 8. Kidney diseases (nephritis, nephrotic syndrome, etc.) | Top killer diseases in 2008: Male 1. Cancer 2. Cerebrovascular diseases (stroke) 3. Respiratory diseases 4. Heart diseases (incl. HT heart disease) 5. Injury and poisoning 6. Diseases of the digestive system 7. Endocrine, nutrition and metabolic diseases (e.g. diabetes mellitus (DM)) 8. Kidney diseases (nephritis, nephrotic syndrome, etc.) |

Female 1. Cancer 2. Heart diseases (incl. HT heart disease) 3. Cerebrovascular diseases (stroke) 4. Respiratory diseases 5. Injury and poisoning 6. Endocrine, nutrition and metabolic diseases (e.g. diabetes mellitus (DM)) 7. Diseases of the digestive system 8. Kidney diseases (nephritis, nephrotic syndrome, etc.) | Female 1. Cerebrovascular diseases (stroke) 2. Cancer 3. Respiratory diseases 4. Heart diseases (incl. HT heart disease) 5. Injury and poisoning 6. Endocrine, nutrition and metabolic diseases (e.g. diabetes mellitus (DM)) 7. Diseases of the digestive system 8. Kidney diseases (nephritis, nephrotic syndrome, etc.) |

Common chronic diseases: 1. Hypertension 2. Diabetes mellitus 3. Cerebrovasclar diseases 4. Coronary heart disease 5. Intervertebral disc disease 6. Gastroenteritis 7. Rheumatoid arthritis 8. Chronic obstructive airway disease 9. Choleltih and cholecystitis 10. Peptic ulcers | Common chronic diseases: 1. Hypertension 2. Gastroenteritis 3. Rheumatoid arthritis 4. Intervertebral disc disease 5. Cerebrovasclar diseases 6. Chronic obstructive airway disease 7. Choleltih and cholecystitis 8. Diabetes mellitus 9. Coronary heart disease 10. Peptic ulcers |

Source: Ministry of Health of China. China Health Statistics [Abstract], 2008.25

In the Hong Kong SAR, the top killer diseases in the elderly include cancer, heart diseases and pneumonia,12 while common chronic diseases include arthritis, hypertension and diabetes mellitus13, 15, 27–30 (Table 146.6).

Table 146.6 Mortality and morbidity of the elderly in Hong Kong.

Leading causes of death in the elderly in 2001: 1. Cancer 2. Heart diseases (incl. HT heart disease) 3. Pneumonia 4. Cerebrovascular diseases (stroke) 5. Chronic lower respiratory disease 6. Kidney diseases (nephritis, nephrotic syndrome, etc.) 7. Diabetes mellitus (DM) 8. Injury and poisoning |

Common chronic diseases: 1. Arthritis 2. Hypertension 3. Bone fracture 4. Peptic ulcers 5. Diabetes mellitus 6. Coronary heart disease 7. Hyperlipidaemia 8. Dementia 9. Hyperthyroidism 10. Chronic obstructive airway disease 11. Stroke 12. Asthma |

Source: Chu, 199813; Woo, 199715; Chiu, 199827; Chu, 200528; Lau, 199729; Leung, 199730

Healthcare Services in Mainland China

China’s healthcare delivery system is organized in a three-tier fashion. In urban areas, it consists of street health stations, community health centres and district hospitals. In the economically less-developed rural areas, village stations, township health centres and county hospitals are responsible for healthcare delivery. Doctors in the village stations receive only six months training (i.e. no formal medical school) after junior high school and receive an average of 2–3 weeks ongoing education every year. Township health centres usually have 10–20 beds and are looked after by a physician with 3 years of medical school education after high school. They are supported by assistant physicians and village doctors. County hospitals usually have 250–300 beds and are staffed by physicians with 4–5 years of medical training after high school. They are assisted by nurses and technicians.5, 22, 31

Healthcare costs in old age are an important problem for the poor and those living in rural areas. If they cannot afford the costs, they will be denied access to healthcare. In the olden days, the rural Cooperative Medical System (CMS) schemes primarily provided funding and organized prevention, primary care and secondary healthcare for the rural population. After 1950, a mutual assistance mechanism was established to provide access to basic drugs and primary healthcare. During the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976), the CMS was given a political priority. The rural CMS then organized health stations, paid village doctors to deliver primary healthcare, provided drugs and partially reimbursed patients for services received at township centres and county hospitals. China’s relative success in extending healthcare to the rural population has played a key role in improving the health status of the population. However, the CMS suffered from problems of poor management and a small risk-pooling base, contributing to the downfall of these early cooperative financing schemes after the initiation of agricultural reforms in 1980. The CMS has gradually disintegrated in most rural areas. In 2004, fewer than 10% of China’s villages had a CMS scheme. In addition, many village doctors have left to go into farming or to become private practitioners. Township health centres and county hospitals are largely financed by fee-for-service and out-of-pocket payment. Access to healthcare in many areas is principally governed by the ability to pay rather than the need for healthcare. Many elderly persons in villages face bankruptcy if they have a major illness and have to be hospitalized. For example, the cost of one average hospitalization would exceed the average annual income of 50% of the rural population. The insurance coverage level of the primarily village-based community financing schemes in rural areas is severely limited. Poverty after an illness and the related treatment expenses continues to be a serious problem for the rural elderly, and they are often deprived of the needed medical care because of their inability to pay. Reform of the rural CMS is needed. In May 1997, the State Council issued a special document emphasizing that CMS reform was a major direction for China’s rural health reform.31

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree