Abstract

This chapter addresses the role of genetic counseling in the diagnosis of hereditary syndromes, particularly hereditary endocrine diseases. Genetic counseling is a communication process that encompasses risk assessment, informed consent, psychosocial support, and a discussion of the risks and benefits of genetic testing. Genetic counselors use their training in the medical, psychosocial, ethical, and legal aspects of genetic medicine to help individuals and families understand and adapt to the implications of genetic contributions to disease, make decisions about genetic testing, and consider reproductive choices and other aspects that might affect their life and future. Genetic conditions include many of the health, growth, or developmental problems seen at birth, while others may not be noticed until later in life; genetic counseling can take place anywhere along the continuum of life. Genetic counselors may specialize in particular areas of interest such as cancer, prenatal, pediatrics, and assisted reproduction. Their role on the healthcare provider team is becoming even more critical in the era of “personalized medicine” and next-generation sequencing as they are trained in communicating and interpreting the complex genetic information acquired from these types of tests.

Keywords

genetic counseling, genetic testing, next-generation sequencing, endocrine tumor syndromes, personalized medicine

Introduction

The completion of the Human Genome Project in 2003 ushered in a new era in genetics research and medicine and garnered much hope for “discovering the genetic basis for health and the pathology of human disease.” Indeed, the Human Genome Project laid the foundation for the next generation of investigations into Mendelian and complex disease through genome-wide association studies and, most recently, whole-genome and exome sequencing. However, the amount of scientific information acquired from sequencing (nearly) the entire human genome is immense, and we are now at a crossroads, where our technology and ability to amass genetic information has far surpassed our interpretation and application of the derived material. Nonetheless, genetics is becoming increasingly integrated into healthcare in the name of “personalized medicine,” and as such, healthcare providers must understand the sensitive and unique nature of communicating genetic information to patients. Genetic counselors can assist with this communication process. They are healthcare professionals trained in medical genetics and counseling that work with individuals and families to help them understand and adapt to the implications of genetic contributions to disease, make decisions about genetic testing, and consider reproductive choices and other aspects that might affect their life and future. Genetic counseling can make a difference for families, whether it is a one-time visit or multiple sessions over a long period. The role of genetic counselors continues to expand and adapt to the new developments in genetic testing, and the growing role of genetic counseling in endocrinology will be highlighted here.

The genetic counseling profession

The practice of advising people about inherited traits began around 1906, shortly after Bateson named this new medical and biological study of hereditary “genetics.” However, it was not until Sheldon Reed coined the term “genetic counseling” in 1947 that the mechanism for translating the advances in genetics to clients had a name. Scientists and the public were becoming fascinated by the idea that this new science might identify hereditary elements contributing not only to medical disorders, but also to social and behavioral conditions such as crime and mental illness. This enthusiasm took an awful turn when the eugenics (Greek term meaning “well-born”) movement took hold and sought to institute “agencies under social control to improve or impair racial qualities of future generations, either physically or mentally.” These governmental agencies not only collected data on human traits but sometimes provided that information to affected families, usually with the intent of convincing them not to reproduce. In many cases, the data were scientifically unsound or tainted by political or social agendas. The granddaddy of all atrocities was the legalization of euthanasia for the “genetically defective” in Germany in 1939. This led to the deaths of over 70,000 people with hereditary disorders, in addition to the hundreds of thousands of Jews and others killed in the Holocaust. It is through these early history lessons that the art of “nondirective” counseling grew and is the approach instilled in every practicing genetic counselor today. This approach ensures that clients are aware of concerns relevant to their situation and helps them make decisions to fit their lifestyle and belief system.

Today, genetic counselors interact with clients and other healthcare professionals in a variety of clinical and nonclinical settings, including, but not limited to, university-based medical centers, private hospitals, private practice, and industry settings. Most genetic counselors have a master’s degree from an accredited genetic counseling training program. The first class of genetic counselors graduated from Sarah Lawrence College in 1971. Currently, there are over 3,000 board-certified genetic counselors in the United States. A limited number of genetic counselors also practice in Canada, Australia, and throughout Europe. Genetic counselors are board-certified by the American Board of Genetic Counseling. Board eligibility or certification is required for employment in many positions, and many states now license genetic counselors. The National Society of Genetic Counselors, Inc. (NSGC) was incorporated in 1979 and is the only professional society dedicated solely to the field of genetic counseling. Its mission is to “advance the various roles of genetic counselors in healthcare by fostering education, research, and public policy to ensure the availability of quality genetic services.”

There are currently over 2,500 clinical genetic tests available to clinicians, and providers are increasingly expected to be aware of the advances in genetics to better serve and counsel their clients. Because the majority of people seek their medical care in the community and may not have access to genetic counselors or genetic specialists, the burden of genetic interpretation and guidance is being shared by the wider clinical community. Other healthcare professionals that are trained to provide genetic counseling services include medical geneticists and clinical nurse specialists trained in genetics. Although all healthcare professionals should be competent in genetics, data shows that many medical providers have difficulty interpreting even the most basic pedigrees and genetic test results. For this reason, it is preferable for individuals who warrant evaluation to be seen by a genetic counselor or genetics expert. Access to these services is now widely available through internet, telephone, and satellite-based telemedicine services, and several major health companies cover these services. Table 28.1 lists organizations and their websites for locating professional genetic experts.

| Organization | Website |

|---|---|

| American Board of Genetic Counseling | www.abgc.net |

| American College of Medical Genetics | www.acmg.net |

| Canadian Association of Genetic Counselors | www.cagc-accg.ca |

| GeneClinics | www.geneclinics.org |

| Genetic Centers in the British Isles | www.cafamily.org.uk/gencentr |

| Informed Medical Decisions | www.informedDNA.com |

| International Society of Nurses in Genetics | www.isong.org |

| March of Dimes | www.marchofdimes.com |

| National Cancer Institute | http://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/causes-prevention/genetics/directory |

| National Society of Genetic Counselors | www.nsgc.org |

The role of genetic counselors on the healthcare provider team

The role of the genetic counselor has evolved greatly since 1971. Initially, genetic counselors worked almost exclusively in clinical settings under physician supervision, seeing clients who had been diagnosed as having a genetic disorder, were at risk for developing a genetic disorder, or were at risk for having a child with a genetic disorder. They would assess risk, provide information, and discuss available testing options and provide appropriate supportive counseling. The variety of clients and the information and testing options offered by genetic counselors was greatly restricted by the limited technology and genetic knowledge of the time. Today, because of the Human Genome Project and other advances, genetic counselors are now able to offer a wider array of services and options. They are able to specialize in a particular area of interest, such as cancer, prenatal, pediatric, assisted reproduction, and metabolic or neurogenetic disorders to name a few. Most genetic counselors still work in the clinical setting, either in a hospital or in private practice. However, advances in genetics have enabled genetic counselors to work in a variety of other settings including research, public health, education, private practice, and industry.

The Role of Genetic Counselors on the Endocrinology Team

Given the complexity of endocrine disorders, a multidisciplinary approach with coordination of care with multiple healthcare specialists is the ideal medical management scenario. Such a team should include endocrinologists, surgeons, radiology/nuclear medicine, pathologists, and genetic counselors. The inclusion of genetic counselors on these teams is critical as our understanding of the hereditary nature of endocrine tumors increases, and options for genetic testing are expanding. Genetic counselors can assist the endocrinology team by eliciting a detailed pedigree, determining the appropriate genetic test to order, obtaining informed consent, interpreting complex genetic test results, providing psychosocial and family counseling, and assessing which family members are at risk.

Genetic testing for the RET oncogene has long been considered the standard of care for managing individuals and family members suspected of having multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2 (MEN2). Increasingly, the importance of genetic testing and counseling is being recognized for other endocrine tumor syndromes, including well-established syndromes such as multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN1), and newer entities such as hereditary pheochromocytoma (PCC), paraganglioma (PGL), and familial nonmedullary thyroid cancer (FNMTC). Table 28.2 highlights features of endocrine disorders that should prompt referral for genetic counseling and testing, while Table 28.3 describes the associated hereditary syndromes and their related benign and malignant tumors of the endocrine system. Any individual with two or more features of these syndromes should also be referred for genetic counseling.

| Medullary thyroid cancer (any age) |

| Familial nonmedullary thyroid cancer (2+ affected family members) |

| Multigland primary hyperthyroidism before age 40 |

| Parathyroid carcinoma |

| Multifocal pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors |

| Pheochromocytoma or paraganglioma diagnosed before age 50 |

| Malignant or multiple pheochromocytoma or paraganglioma (any age) |

| Adrenocortical carcinoma diagnosed before age 40 |

| Syndrome (gene) | Thyroid | Pituitary | PHPT | Adrenal cortex | PCC/PGL | PNET | Foregut carcinoid | Other main features |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 ( MEN1 ) | Low (adenomas) | 20–60% | >95% | 20–50% (benign) | 50–75% | 5–10% | Facial angiofibromas, collagenomas, and lipomas | |

| Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2A/B, familial medullary thyroid cancer ( RET ) | >95% (medullary) | Up to 30% | Up to 50% | Mucosal neuromas, marfanoid habitus in MEN2B | ||||

| Von Hippel-Lindau ( VHL) | 10–60% | 10% | Hemangioblastomas, renal cancer/cysts | |||||

| Familial PCC/PGL ( SDHB , SDHC , SDHD , others) | Low (nonmedullary) | Up to 80% | Renal cancer GIST | |||||

| Li Fraumeni ( TP53 ) | Low (nonmedullary) | Low | Breast cancer, sarcoma brain tumor, and leukemia. | |||||

| Cowden syndrome ( PTEN ) | 35% (follicular) | Benign skin tumors breast/uterine/renal/colon cancer | ||||||

| Carney complex ( PRKAR1A ) | Nodules common, low cancer risk | 10% | 25% (PPNAD) | Lentigines, myxomas Schwannoma | ||||

| HPT-jaw tumor syndrome ( HRPT2 aka CDC73 ) | >90% (15% cancer) | Jaw, uterine tumors, and kidney cysts/tumors | ||||||

| FAP ( APC ) | 1–2% (cribiform morular) | Low | Colon polyposis and cancer | |||||

| Neurofibromatosis type 1 ( NF1 ) | <5% | Low | Café au lait spots and neurofibromas |

In MEN1, individuals diagnosed through genetic testing have been shown to fare better than those diagnosed by clinical expression, with fewer clinical manifestations and lower frequencies of malignancies. Individuals with MEN1 managed by a multidisciplinary team that included medical geneticists and/or genetic counselors also had improved long-term outcomes, including increased detection of early-stage disease, which led to more efficacious treatment and reduced morbidity and mortality from hormone excess and malignancy. Affected individuals may also suffer less psychological distress when managed in these types of settings. Recently published clinical practice guidelines for MEN1 strongly advise that all individuals offered MEN1 mutation testing undergo genetic counseling before testing.

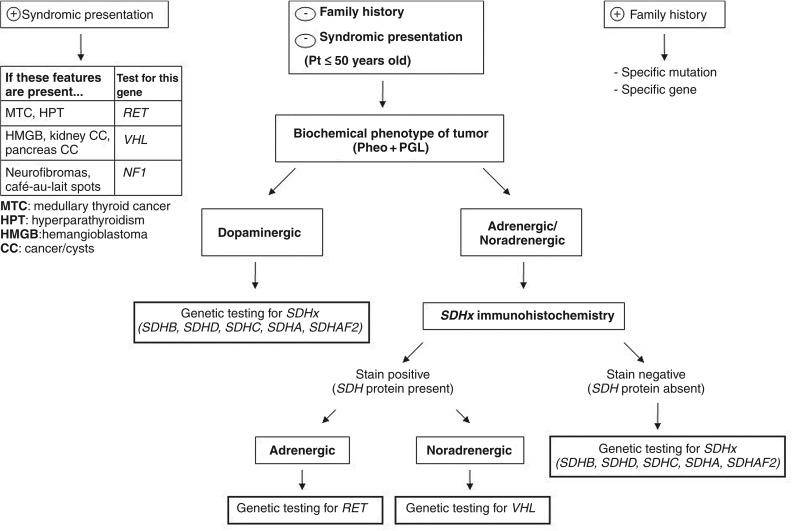

Genetic testing and counseling for individuals diagnosed with PCC or PGL is particularly adventitious because up to one-third of these tumors are caused by germline mutations in one of 10 genes. This high proportion of hereditary causes may warrant genetic testing in every individual presenting with a PCC or PGL, regardless of age or family history. There have been numerous algorithms developed for genetic testing that incorporate certain clinical, biochemical, and histological features of the tumors, including our algorithm in Fig. 28.1 . Immunohistochemical staining of tumor tissue for SDH proteins, particularly SDHB, is a relatively new technique that is not yet widely available but demonstrates high specificity. The advent of next-generation sequencing has opened up new avenues of germline testing that can incorporate all the clinically available genes on a single targeted gene panel. Next-generation sequencing technology uses massively parallel sequencing to analyze thousands to millions of simultaneous sequences. If there is more than one differential diagnosis being considered, this type of testing can be very cost-effective and time saving. Currently, Ambry Genetics offers the only clinically available gene panel that specifically targets PCC and PGL. The test is called PGLNext™ and analyzes 10 genes associated with an increased risk of developing PGL and/or PCC, including MAX , NF1 , RET , SDHA , SDHAF2 , SDHB , SDHC , SDHD , TMEM127 , and VHL . The current cost of the test is $3,900, which represents significant cost savings as testing for just six of these genes ( RET , VHL , NF1 , SDHD , SDHB , and SDHC ) sequentially could cost up to $7,700. Genetic counselors can help decide which type of testing is most appropriate, which could potentially decrease the costs of testing.