TABLE 23.1 Risk Factors for Development of Squamous Cell Carcinoma | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

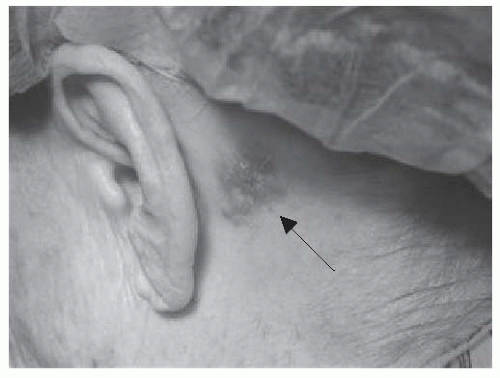

FIGURE 23-2. Retroauricular basal cell carcinoma presenting as apearly plaque with numerous telangiectasias. Source: Photo courtesy of Dr. Ratner. |

texture and are oftentimes more easily palpated than visualized. These lesions commonly occur in a typical sun-exposed distribution, including the face, scalp, and dorsal hands. Histologically, actinic keratoses consist of atypical keratinocytes confined to the basilar layers of the epidermis with overlying parakeratosis. Estimates of the rate of progression to SCC vary from 0.025% to 20% per year.45,46

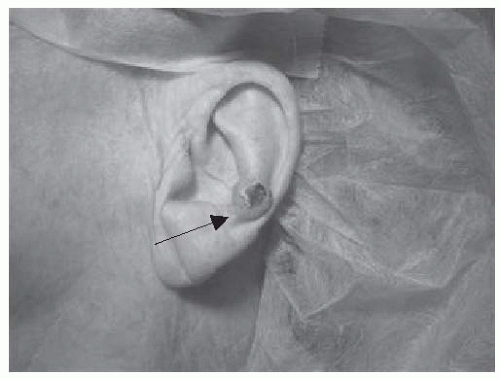

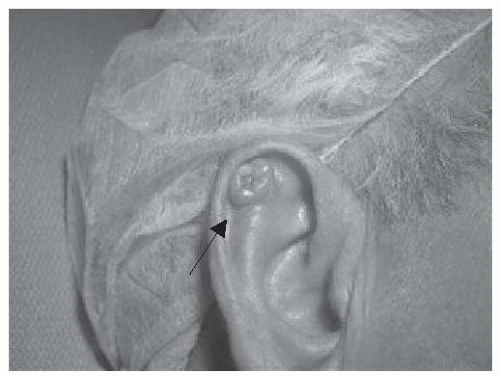

FIGURE 23-3. Basal cell carcinoma of the antihelix. Central erosion of the lesion is characteristic and referred to as a rodent ulcer. Source: Photo courtesy of Dr. Ratner. |

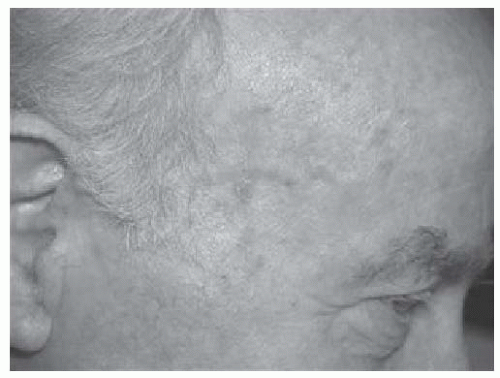

FIGURE 23-4. Numerous actinic keratoses on the temple of a man with extensive photo damage. Source: Photo courtesy of Dr. Ratner. |

prominent region where cosmetic results of treatment are particularly important. Local extension is through pathway of least resistance, including fascial planes, periosteum, perichondrium, and nerve sheaths. High-risk features of BCC are shown in Table 23.2. The primary tumor stage may be the most significant factor in determining the progression of disease. BCCs rarely metastasize to lymph nodes or distantly, and most cases are associated with T3 or T4 tumors. In addition, locally advanced tumors are more likely to have perineural invasion, which can result in cranial nerve palsies. Periorbital lesions have potential for invasion into the ethmoid sinuses and subsequently to the base of skull. The incidence of nodal metastases from BCC is exceedingly rare, between 0.01% and 0.5%, and associated with high-risk tumor features.44,52 However, the prognosis is poor after spread of disease, with median survivals between 8 months to 3 years. Distant spread of disease is to the lymph nodes, followed by bone, the lung, and the liver.

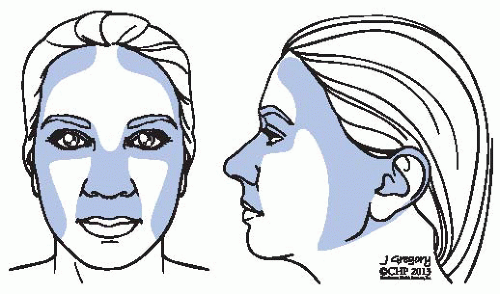

FIGURE 23-6. Anatomic depiction of the “H-zone” including areas associated with higher recurrence rates. |

TABLE 23.2 Risk Factors for Basal Cell Carcinoma (BCC) Recurrence | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

TABLE 23.3 Factors Predisposing to Recurrence and Metastasis of Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma (SCC) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are used to evaluate these tumors. For SCC, CT with contrast should be done to evaluate the primary echelon of nodes to determine if the disease has spread regionally. Positron emission tomographic (PET) scan may also play a role for patients with high-risk SCC. Cho et al. showed PET correlation with both local and distant disease extent for all nine patients with high-risk features.67 Another modality is the use of high-frequency ultrasonography to determine the depth of the lesion. A study by Lassau et al. examined 32 patients with BCC and was able to identify each as hypoechoic on ultrasonography.68 Perhaps of more importance, 29% of BCC lesions were found to be larger than that predicted by clinical examination. This may represent an important tool in the pretreatment setting.

TABLE 23.4 American Joint Cancer Committee (AJCC) 6th Edition Staging for Nonmelanoma Skin Cancer (NMSC) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

TABLE 23.5 American Joint Cancer Committee (AJCC) 6th Edition Staging for Eyelid Tumors | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree