Classification and Histology of NPC

Diagnosis. Tumors arise from the nasopharyngeal epithelium and may present as frank tumor with ulceration or as occult submucosal lesions. Diagnosis is made by pathologic confirmation usually by biopsy. Biopsy may show solid sheets, irregular islands, dyscohesive sheet, and trabeculae of tumor with interspersed lymphocytes and plasmas cells.

5 Undifferentiated subtype is characterized by syncitial appearing large tumor cells with scant cytoplasm and indistinct borders, round to oval vesicular nuclei, and large central nucleoli. Differentiated subtype shows cellular stratification and pavementing with plexiform growth similar to transitional cell carcinomas with less prominent nucleoli.

Immuhohistochemistry shows virtually all tumor cells staining strongly for pan-cytokeratin (AE1/AE3) and high-molecularweight cytokeratins.

5 Nearly all nonkeratinizing tumors, including differentiated and undifferentiated subtypes, will show EBV viral infection, best detected by

in situ hybridization for EBV encoded early RNA localized in the nuclei of tumor cells.

Fine-needle aspiration (FNA) of a neck node showing clusters of cohesive tumor cells with vesicular nuclei and prominent nucleoli that is cytokeratin positive and leukocyte common antigen (LCA) negative can detect an occult nasopharyngeal primary or residual/recurrent disease.

37 Fine-needle aspiration has a diagnostic sensitivity of 70% to 90%.

5 Cytologic examination of nodes shows a background of lymphocytes and plasma cells with irregular clusters of large cells with overlapping vesicular nuclei and large nucleoli. The diagnosis is confirmed by

in situ hybridization for EBV and immunostaining for cytokeratins, which rules out a diagnosis of lymphoma.

Classification. According to the World Health Organization (WHO) classification of head and neck carcinomas, NPCs encompass (keratinizing) squamous cell carcinoma, nonkeratinizing carcinomas, and basaloid squamous cell carcinoma.

38 Prior designations for these tumor types are no longer used and included WHO I for squamous cell carcinomas, WHO II for nonkeratinizing carcinoma (also previously referred to as transitional cell carcinoma), and WHO III for undifferentiated carcinoma; the latter also previously referred to as lymphoepithelioma, Schminke-type lymphoepithelioma, and Regaud-type lymphoepithelioma.

38

The squamous cell carcinomas include well-, moderately and poorly differentiated carcinomas. Keratinizing carcinomas comprises <0.3% in southern China and about 3% in Hong Kong

2,3 but about 25% of all NPC in North America and has a conventional keratinization pattern with intercellular bridges, squamous pearls and graded as well, moderately, or poorly differentiated. It is associated with a desmoplastic response due to invasive growth.

5 It rarely occurs in patient younger than 40 years. These carcinomas are not associated with EBV.

38The category of nonkeratinizing carcinomas is subdivided into differentiated and undifferentiated types. The nonkeratinizing carcinoma, differentiated type shows little to absent keratinization and typically lacks a desmoplastic response. It represents about 12% of all NPCs both in Hong Kong and in North America

5,39 and has a growth pattern similar to transitional carcinoma of the bladder with stratified cells well-delineated from the surrounding stroma. Growth may be papillary or plexiform. This tumor type may show prominent cystic degeneration with associated necrosis, and such lesions may metastasize to the cervical neck as cystic metastatic carcinoma. The nonkeratinizing carcinoma, differentiated type, is associated with EBV.

38The nonkeratinizing carcinoma, undifferentiated type represents 60% of all NPC in adults and is the most frequent type in the pediatric population. The cells of undifferentiated carcinoma have prominent eosinophilic nucleoli with dispersed to vesicularappearing nuclear chromatin and a round nucleus often with prominent eospinophilic nucleoli.

5 In contrast to the other NPC types, the cell margins of this carcinoma are often indistinct creating a syncitial growth pattern. A prominent benign lymphoid component is usually present, and despite invasive growth there is often an absence of a desmoplatic response. As such, in the face of a prominent lymphoid cell proliferation that may overrun the neoplastic cells and the absence of a desmoplastic response, it may be difficult by histologic evaluation to identify the presence of invasive carcinoma. In this setting, the use of cytokeratin staining will greatly facilitate the identification of the malignant cells. Furthermore, the cytomorphologic features of the neoplastic cells as well as the tendency to grow in a dyscohesive manner may result in diagnostic confusion with a non-Hodgkin’s malignant lymphoma. Since the neoplastic cells are of epithelial origin, they will be immunoreactive for epithelial markers (e.g., cytokeratins) and negative for lymphoid markers (e.g., leucocyte common antigen, others). The nonkeratinizing carcinoma, undifferentiated type can have a syncitial growth with cohesive cells (Regaud type) or a diffuse cellular infiltrate with independent, dyscohesive cells (Schmincke type). The growth characteristics of a given neoplasm has no bearing on the diagnosis, therapy, or prognosis of these neoplasms, and these two have no distinctly different clinical behavior compared with each other.

5 The nonkeratinizing carcinoma, undifferentiated type is highly associated with EBV.

38All three histologic types stain positive for cytokeratin and negative for leukocyte common antigen. Also, these three types may overlap with each other in up to 26% of cases

40 but the tumor will be classified according to the dominant component.

The categories have distinct clinical implications.

40 Undifferentiated NPC has a predilection for dissemination to regional nodes and distant sites and are radioresponsive. The keratinizing squamous cell carcinomas behave like those in other head and neck sites, typically occurring in patients 40 years or older and associated with a smoking/drinking history.

6 Nasopharyngeal squamous cell carcinomas tend to present with more locally advanced primary tumors with fewer involved nodes and metastases than the nasopharyngeal nonkeratinizing carcinomas but with increased radioresistance compared with the other two.

40,41,42,43,44 Overall survival is lower for patients with nasopharyngeal squamous cell carcinomas compared with those with nasopharyngeal nonkeratinizing carcinoma, undifferentiated type.

40,45,46,47 Five-year disease-free survival is reported to be 15% to 42% lower with squamous cell carcinoma versus nonkeratinizing carcinoma, undifferentiated type.

41,43,48 The nonkeratinizing carcinoma, differentiated type is clinically more similar to nonkeratinizing carcinoma, undifferentiated type than to squamous cell carcinoma and are associated with elevated EBV serology.

49Basaloid squamous cell carcinoma, a high-grade variant of squamous cell carcinoma, can rarely occur as primary tumor of the nasopharynx. It is morphologically identical to the same tumor more commonly occurring in other head and neck sites, such as the hypopharynx (pyriform sinus) and larynx. Histologically, the tumor is infiltrative composed of lobules, festoons, trabeculae, and solid foci of pleomorphic, mitotically active basaloid cells with pale-staining nuclei, interspersed with variable amounts of mucoid matrix or hyaline material. Comedo necrosis is common. Neurotropism is often identified. An identifiable squamous cell carcinoma, either in the form of invasive carcinoma or in situ, is often identified but may be absent. When present, it usually is limited in extent and represents a minor component in this carcinoma. Immunohistochemical staining is consistently reactive for epithelial markers including cytokeratins (AE1/AE3, CAM5.2, CK903, others) and epithelial membrane antigen. Neuroendocrine markers, including chromogranin and synaptophysin, are typically absent but in rare case may be positive. Melanocytic markers are negative.

Carcinomas histologically similar to nasopharyngeal nonkeratinizing carcinomas, differentiated and undifferentiated types, have been found in other head and neck sites including the oropharynx, the Waldeyer ring,

50 the larynx,

51 the thymus,

52 and the major salivary glands.

53 These “lymphoepithelial carcinomas” are infrequent (e.g., <5% of base of tongue and tonsil carcinomas), but their biologic behavior and response to treatment qualifies them further as carcinomas of nasopharyngeal type. The role of EBV in some of these carcinomas is strongly suggested by serologic profiles, presence of EBV-associated nuclear antigen in the carcinoma cells, and by high levels of viral genomes in the DNA.

Signs and Symptoms

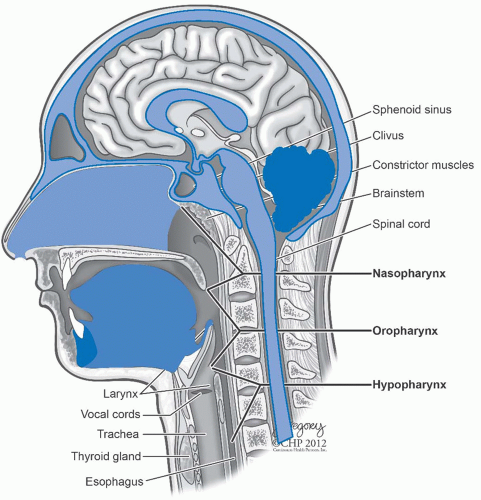

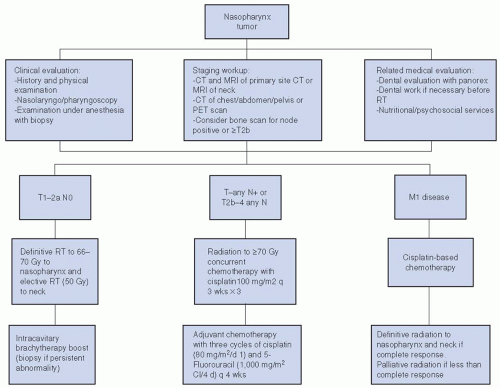

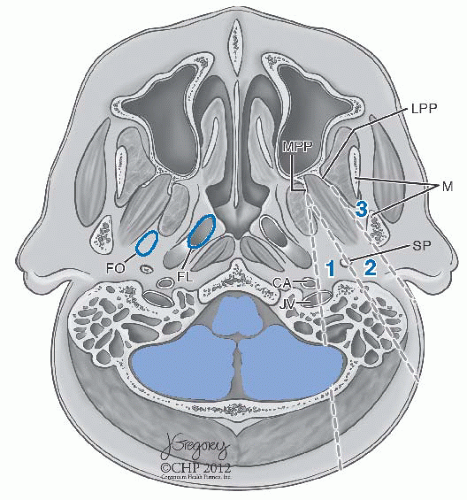

Patterns of Spread and Clinical Presentation. NPC, especially of the WHO types II and III, usually arises in the region of the fossa of Rosenmüller.

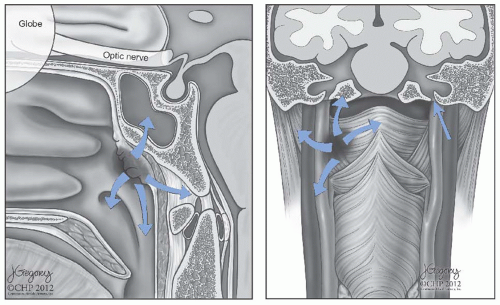

4 The primary tumor may extend anteriorly into the nasal cavity, superiorly into the floor of the sphenoid sinus, anterosuperiorly into the posterior ethmoid air cells and the orbits, laterally into the parapharyngeal space and the pterygoid muscles, superiorly into the foramen lacerum and the sphenopalatine fossa, and inferiorly into the oropharynx (

Fig. 22-2).

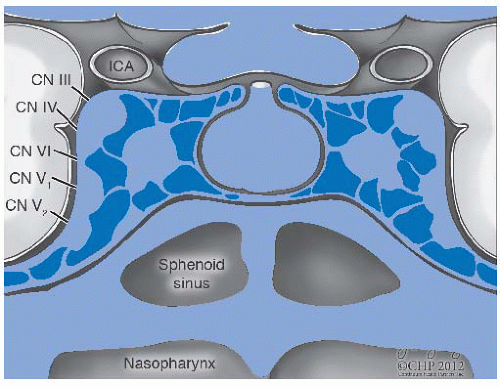

38 Tumor extension through the fibrocartilage of the foramen lacerum enables direct entry into the cavernous sinus and the middle cranial fossa, resulting in cranial neuropathy including diplopia due to involvement of cranial nerve VI as well as facial pain and paresthesias due to infiltration of the branches of cranial nerve V. Involvement of cranial nerves III and IV indicates more advanced disease along the cavernous sinus (

Fig. 22-3). Tumor extension into the parapharyngeal space and involve cranial nerves IX, X, and XI, thus producing a jugular foramen syndrome.

First echelon lymphatic spread most commonly involves the superior jugular, the retropharyngeal, and the posterior cervical chain nodes.

38 Ninety percent of patients will have clinical evidence of unilateral nodal involvement whereas 50 % will have bilateral lymphadenopathy. Involvement of the upper jugular and the posterior chain nodes are usually painless unless very large. However, retropharyngeal lymph node metastasis, when extensive, produces a characteristic syndrome of pain referred to the ipsilateral neck, ear, head, forehead, and the orbit. It may be associated with a stiff neck or pain upon neck flexion.

Patients most commonly present with a painless neck mass in more than one-third, whereas other common manifestations including hearing loss or ear drainage in about one-quarter and nasal bleeding or obstruction. Nasal symptoms including breathing obstruction, epistaxis, and discharge can occur. A small proportion of patients may present with cranial nerve deficit, most commonly involving the cranial nerves VI and V (V2 most commonly). Patients may also present with facial pain, headaches, or neck discomfort. Proptosis will occur when cancer invades through the posterior portion of the orbit. Trismus is an indication of the pterygoid muscle invasion.

Physical examination includes inspection of the nasopharynx, either indirectly with a mirror or preferably by direct visualization through a fiberoptic endoscope. The tumor usually appears as an asymmetric mass with telangiectasia on its friable surface and is centered in the fossa of Rosenmüller. Depending on the size of the primary tumor, distortion of the soft palate can occur. Straw-colored serous otitis media is usually unilateral. The earliest signs of cranial nerve involvement are usually extraocular muscle dysfunction, especially lateral rectus palsy, and signs of trigeminal nerve involvement such as hyperesthesia and atrophy of masticatory muscles.

For patients in whom the tumor in the nasopharynx is clinically obvious, biopsy can usually be done under the topical anesthetic by topical anesthetic applications through the nasal cavity. Sometimes, however, no primary lesion is evident in the nasopharynx but NPC is suspected on the basis of the presence and location of the cervical lymph nodes. In such cases, fine-needle aspiration cytology will usually establish whether the cell type is consistent with NPC.

37 Usually, clusters of cohesive tumor cells with vesicular nuclei and prominent nucleoli that stain for cytokeratin are present. If it is, radiologic assessment of the nasopharynx may indicate a target lesion for biopsy at examination under anesthesia. If not, a core biopsy of an involved node will provide tissue for fluorescent

in situ hybridization (FISH) analysis to detect EBV viral genome constituents in the neoplastic cells, which is sufficient to establish the diagnosis of NPC.