Workup and Evaluation

Patients with tumors of the hypopharynx and/or the cervical esophagus should be evaluated in a multidisciplinary fashion, with input from surgeons, medical oncologists, radiation oncologists, speech-and-swallow specialists, social workers, dentists, nutritionists, and often specialists in alcohol and/or tobacco cessation. A detailed history should be elicited, with the nature and duration of symptoms documented, as well as the degree of weight loss. Assessment of dysphagia to both solids and liquids should be noted. Changes in voice quality and the complaint of referred otalgia are frequently present. Exposure in pack-years of cigarette smoking should be noted, as should the use of smoke-free tobacco (chewing tobacco, snuff). Alcohol history should be elicited, with particular attention to current use, which may predispose patients to withdrawal.

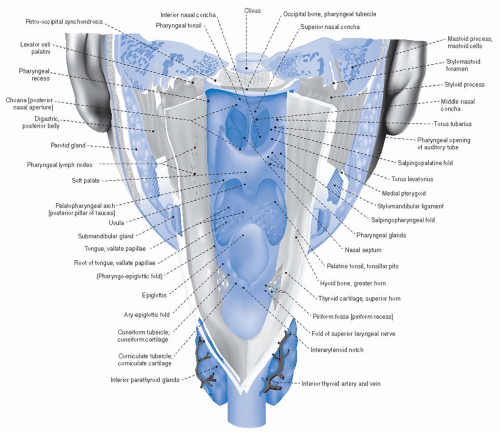

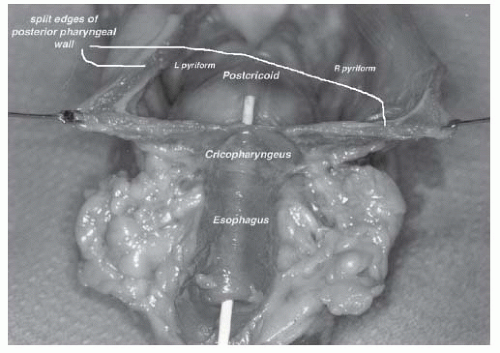

The initial physical examination should indirect visualization of the full laryngopharyngeal axis. Given the high rate of second head and neck mucosal primaries, thorough attention to any other mucosal irregularities is warranted. Tumors of the pyriform sinus can be notoriously difficult to visualize; having the patients puff their cheeks (blow against closed lips) during nasopharyngolaryngoscopy can aid in visualization of the pyriform sinuses. In addition to the primary tumor (size, location, involved structures), particular attention should be paid to the mobility of the vocal cords with phonation, as this impacts tumor staging. Furthermore, the initial examination should include an assessment of dentition, particularly if (chemo)radiation is likely to be employed as a treatment modality. Unlike many tumors of the head and neck region, where indirect visualization may suffice, direct visualization under anesthesia is warranted in most tumors in these locations to fully delineate the extent of tumor spread and for biopsy confirmation of malignancy. An upfront thorough assessment of dentition allows for dental extractions, if needed, to be performed simultaneously while the patient is under anesthesia for tumor mapping under direct visualization (

Table 19.2).

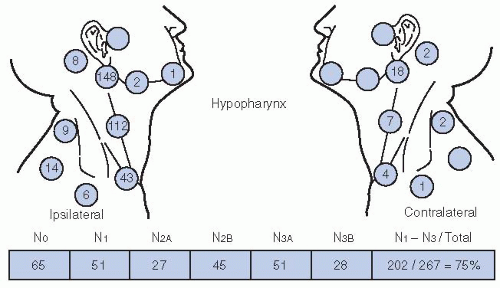

Physical exam should include assessment of cervical lymphadenopathy, providing a description of the size, location, number, mobility, and texture of suspicious lymph nodes. As all patients with biopsy-proven malignancies of the hypopharynx and/or the cervical esophagus warrant advanced radiographic imaging, fine-needle aspirate of enlarged lymph nodes to further confirm metastatic lymphadenopathy is rarely of value and should not be routinely performed.

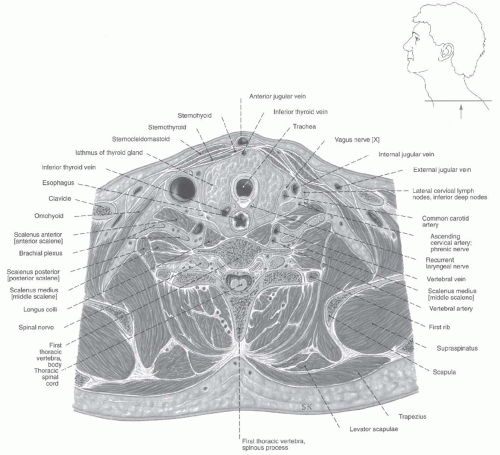

Panendoscopy should be complemented by advanced imaging to assess the extent of the primary tumor and rigorously assess cervical lymph node chains for presence and/or extent of regional lymph node involvement. High-resolution computed tomography (CT) with contrast from the base of skull to below the clavicles is usually the imaging study of choice, although MRI can be utilized. A low threshold should be utilized in extending a CT through the lungs distally, as tumors of the hypopharynx and cervical esophagus have significant rates of pulmonary metastases at presentation. For the rare early-stage, lymph nodenegative hypopharyngeal tumor, chest x-ray may suffice to rule out distant pulmonary metastases. Cervical esophageal tumors in particular commonly involve the lymph nodes of the upper mediastinum

25 and may have thoracic esophageal involvement,

27 and therefore CT imaging should routinely include the thorax in these patients.

18 FDG-PET (or PET-CT, with accompanying CT slice co-registration) is increasingly utilized in the upfront staging of tumors of the hypopharynx and the cervical esophagus. PET-CT allows for detection of distant metastases and provides information that may aide in the determination of lymph node malignant involvement. Furthermore, PET-CT imaging may influence radiation planning, in terms of field design and/or prescribed dose.

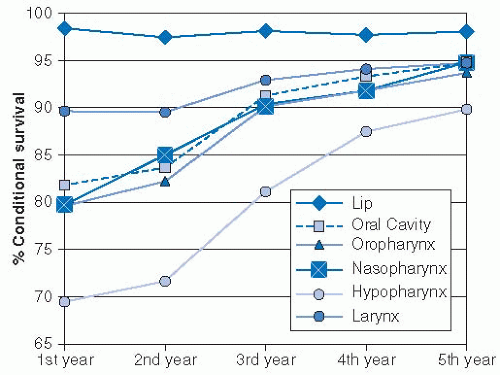

42 A recent prospective study of PET imaging in HNSCC tumor management included 46 patients with hypopharyngeal cancer. Therapeutic decisions were made with physicians blinded, and then unblinded, to FDG-PET imaging data. Tumor/node/metastases (TNM) staging was altered in 100 of 233 enrolled patients (43%), whereas PET altered the management of 32 patients (13.7%) (

Table 19.3). This study, and similar experiences with PET imaging in HNSCC management support a role for PET-CT imaging in the upfront evaluation of patients with hypopharyngeal and cervical esophageal tumors. Worldwide, approximately 75% of oncologists utilize FDG-PET imaging in a proportion of esophageal cancer patients for staging purposes, with routine use slightly more common in North America than in Europe or Asia.

43Patients with cancers of the hypopharynx and/or the cervical esophagus commonly present with significant weight loss,

often as a result of progressive tumor-associated dysphagia and odynophagia. An assessment should be made of the patient’s nutritional status, with attempts to correct nutritional deficits prior to the initiation of aggressive therapy. A nutritionist should be involved as a part of the multidisciplinary team. A percutaneous enteral gastrostomy (PEG) tube is commonly utilized. In surgical patients, a PEG tube is commonly placed at the time of surgery to allow for maintenance of nutrition during the postoperative recovery period. Whether upfront PEG tube placement should occur routinely in patients planning to undergo (chemo)radiation or should happen only in patients who demonstrate significant difficulties with maintaining weight and hydration during radiation is an area of debate. Patients with tumors of the hypopharynx and cervical esophagus tend to have more dysphagia, odynophagia, and prediagnosis weight loss than other HNSCC patients. Therefore, in our experience, the benefits of prophylactic PEG tube placement in terms of improved weight preservation and maintenance of hydration appear warranted for the majority of patients. Therefore, we routinely place PEG tubes during the pretreatment evaluation phase prior to chemoradiation.

In addition to input from a nutritionist, a formal evaluation by speech-and-swallow therapists before initiation of therapy to assess baseline dysphagia is valuable. If swallowing dysfunction is noted, adaptive techniques may be taught to the patient to improve caloric intake and minimize aspiration risks. Although informal bedside assessment may be performed of swallow function, a more definitive fluoroscopic barium swallow study (videopharyngogram or oropharyngeal motility study [OPMS]) is usually preferable. Close posttreatment surveillance with a speech-and-swallow specialist familiar with the patient is important following definitive therapy.

All patients should undergo dental evaluation, with routing cleaning and Panorex imaging to assess for periapical abscesses, unerupted third molars, or other pathology prior to initiation of therapy. For patients who receive (chemo)radiation, long-term xerostomia may result and places patients at risk for accelerated dental decay. Therefore an assessment of teeth in poor repair that may warrant extraction is warranted, especially for any teeth that

occupy a region likely to receive high-dose radiation. Upfront removal of such teeth in poor repair is preferable to subsequent removal following radiation, as manipulation of the teeth and sockets following radiation places patients at risk for osteoradionecrosis. Dental extractions should precede radiation by 10 to 14 days to allow for adequate healing. For patients who have teeth that will remain in place through radiation should receive custom fluoride carrier trays. Long-term use following radiotherapy of fluoride can minimize dental decay in the setting of postradiotherapy xerostomia.

Patients with hypopharyngeal and cervical esophageal cancers commonly have ongoing issues with alcohol addiction and tobacco dependency. Engagement with specialists for counseling and other methods to aide tobacco and alcohol cessation can be valuable. Medications such as the nicotine patch can be prescribed by surgeons and oncologists to assist patients with tobacco cessation. Additionally, many of these patients with benefit from input from social workers, as they often face issues such as financial difficulties, lack of transportation for appointments, and limited family/social support. A case manager or social worker can help these patients navigate the medical system and cope with these concerns through their cancer management.

Staging

In 2009, the American Joint Committee for Cancer (AJCC) updated their staging system, releasing the 7th edition.

44 While the AJCC staging system provides a platform for grouping patients, in order to help guide discussions between physicians and for assessment of outcomes, patient factors include comorbidities, age, and motivation for organ preservation must be taken into account when considering management of an individual patient. For tumors of the hypopharynx, no significant changes were instituted in the 7th edition, with the exception that tumors extending to the esophagus are now T3 (

previously T4a). T1 tumors are <2 cm in greatest dimension and limited to one subsite. T2 tumors measure between 2 and 4 cm, and/or invade more than on subsite of the hypopharynx or an adjacent site. Extension to the esophagus or fixation of the hemilarynx renders a tumor T3, as does size >4 cm. Tumor that invades either the hyoid bone, the thyroid gland, the central compartment soft tissue (

prelaryngeal strap muscles and subcutaneous fat), or the thyroid and/or the cricoid cartilage is deemed moderately advanced local disease (T4a). Tumors are very locally advanced (T4b) if they invade the prevertebral fascia, involve mediastinal structures, or encase a carotid artery. Nodal staging and stage grouping is identical for hypopharyngeal cancer patients as to other HNSCC sites (excluding the nasopharynx).

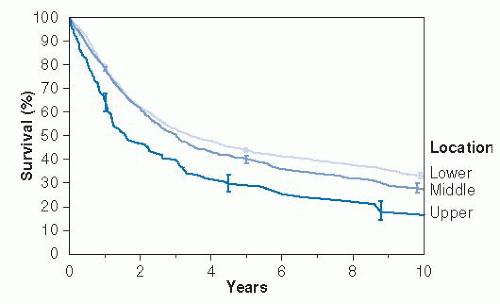

For tumors of the cervical esophagus, major changes were implemented between the 6th (2002) and 7th (2009) editions of the AJCC staging based on a worldwide analysis of 4,627 patients with tumors of the esophagus and esophagogastric junction treated with surgery alone.

3,45 While the previous staging system was based only on tumor/node/metastases criteria, these analyses resulted in histology, grade, and location being incorporated into the stage grouping for 7th edition. T staging of esophageal tumors is based on depth of invasion and remains largely unchanged from the 6th edition of the AJCC staging system. As the vast majority of cervical esophageal tumors are SCC, the tumor (T) and the nodal (N) definitions for esophageal SCC are depicted in

Table 19.4. It should be noted that only 4.1% of the tumors comprising the data set used for derivation of this staging system were located in the upper one-third of the esophagus, which would also include upper thoracic esophageal tumors.

Tis (in situ) is characterized by noninvasive high-grade dysplasia. Tla tumors invade the lamina propria or muscularis mucosae, with invasion of the submucosae staged T1b. T2 tumors invade muscularis propria, whereas T3 tumors invade adventitia. T4 tumors (invading adjacent structures) were split into T4a and T4b in the 7th AJCC system. T4a tumors are resectable tumors invading the pleura, pericardium, or diaphragm. T4b tumors are unresectable, invading other structures including the aorta, the trachea, and the vertebral body.

Nodal (N) staging also changed between the 6th and 7th AJCC staging systems for esophageal tumors. Previously lymph node staging was dependent on the location of lymph nodes, with lymph nodes in the cervical, scalene, internal jugular, periesophageal, and supraclavicular regions termed “regional” for cervical esophageal tumors. Currently, metastases in 1 to 2 regional lymph nodes renders a patient N1, metastases to 3 to 6 regional lymph nodes is N2, and involvement of 7 or more regional lymph nodes is N3. Regional lymph nodes are now designated as any nodes from the cervical nodes to the celiac nodes for all esophageal cancers, whereas previously cervical lymph nodes were deemed metastatic for thoracic esophageal tumors.

Grade and location now are also incorporated into AJCC staging for esophageal SCC, impacting the stage grouping in early-stage tumors (

Table 19.5). Grade that cannot be assessed (grade x) and grade 1 tumors (well-differentiated) are grouped together, whereas grade 2 (moderately differentiated), grade 3 (

poorly differentiated), and undifferentiated (grouped as grade 3 squamous) are grouped together. Furthermore, anatomic location impacts stage grouping. Tumors of the cervical esophagus are defined in this system as being bordered by the hypopharynx superiorly and by the thoracic inlet (sternal notch) superiorly, or from 15 to 20 cm from the incisors by endoscopy.

45