(1)

Department of Pathology Beckley Veterans Medical Center (West Virginia), McGuire Veterans Medical Center, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA, USA

Esophagus

Key Morphological Features of Well-Differentiated Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Dyskeratotic squamous cells

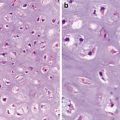

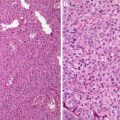

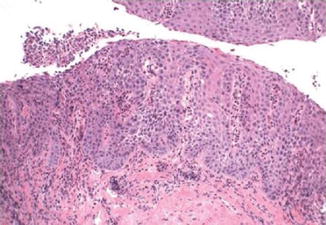

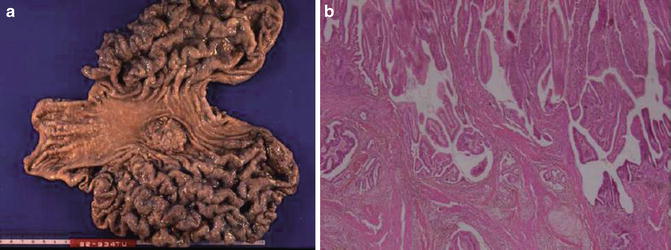

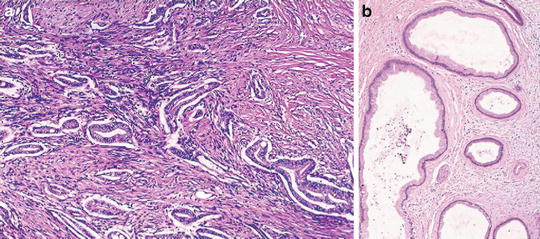

Narrow-based infiltrative or pushing border (Fig. 7.1)

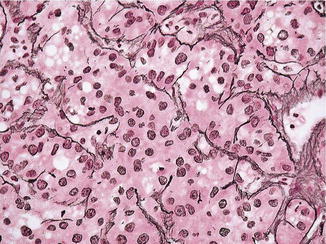

Fig. 7.1

Well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma. Note narrowly based or detached squamous nests with pushing or infiltrative border. Dyskeratotic cells are noted (Surgical Pathology of the GI tract, Liver, Biliary Tract and Pancreas, Elsevier/Saunders, 2009 with permission)

Discussion

The bland squamous cells of well-differentiated squamous cells demonstrate dyskeratosis characterized by early keratinization (keratin pearls in the basal and parabasal layers) and excessive cytoplasmic keratinization. This important feature has been largely overlooked by the surgical pathologists since it is shared by the perfect mimicker of squamous cell carcinoma and pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia. A careful survey of the adjacent tissue in the latter, however, usually reveals an underlying infection, inflammation, trauma, or nonsquamous neoplasm [1, 2].

With the exception of the exceedingly rare variant of esophageal verrucous squamous cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinomas typically show an infiltrative pattern. The infiltrative fronts are usually narrow based with no surface connection. Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia poses a diagnostic problem as in the skin and manifests an infiltrative front as a result of benign epithelial–mesenchymal transition induced by a predisposing lesion [1, 2]. Disruption of the basement integrity results from decreased production of laminin and type IV collagen rather than increased activities of the MMPs. The infiltrative front, however, has a jagged contour with sharp tips which are connected to a broad base. Usually, a connection of the elongated thick invasive projections to the surface can be traced (Fig. 7.2).

Fig. 7.2

Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia. Note lack of dyskeratosis (Surgical Pathology of the GI tract, Liver, Biliary Tract and Pancreas, Elsevier/Saunders, 2009 with permission)

Caveat: The rare variant of esophageal verrucous squamous cell carcinoma has the characteristic morphological features as in the skin. It is composed of exophytic and endophytic components which possess different cytological and architectural changes. The cells have low proliferation activity which is restricted to the basal layer.

Differential Diagnosis

Pseudoepitheliomatous Hyperplasia

Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia has both features of well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma: dyskeratosis and invasive border. However, the adjacent tissue usually shows signs of infection, inflammation, trauma, or other nonsquamous neoplasm. The hyperplastic squamous projections are usually connected to the surface with a broad base and have a jagged contour with pointed tips.

In difficult cases, a panel of immunostainings (p53, MMP-1, and Ki67) should help make the distinction. The neoplastic squamous cells show diffuse positivity for the three markers, whereas the hyperplastic epithelium shows only basal staining. In addition, MMP-1 also shows strong stromal staining in squamous cell carcinoma.

Squamous Dysplasia Involving Mucosal Gland Ducts

The seemingly invasive component has similar cytologic features as the surface dysplastic cells which are usually immature. It lacks an infiltrative or pushing border.

Esophageal Diverticula

Esophageal intramural pseudodiverticulosis can resemble squamous cell carcinoma not only pathologically but also clinically and radiologically [3]. Their involvement of the mucosa and submucosa as well as their irregular shapes simulate invasive squamous cell carcinoma. However, neither dyskeratosis nor an invasive border is present. Other clues of their benignity are their association with the submucosal glandular system and the presence of heavy chronic inflammation.

Squamous Papilloma

It lacks dyskeratosis and an infiltrative front. Even in the endophytic growth pattern, a well-circumscribed appearance is discernible. The epithelial cells might have reactive changes but no dyskeratosis.

Key Morphological Feature of Well-Differentiated Esophageal Adenocarcinoma

Irregularly shaped and sized glands with no serration

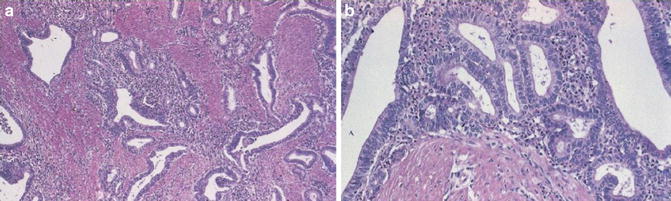

Lack of a layer of periglandular myofibroblasts or myoepithelial cells (Fig. 7.3)

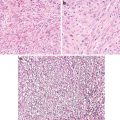

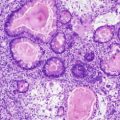

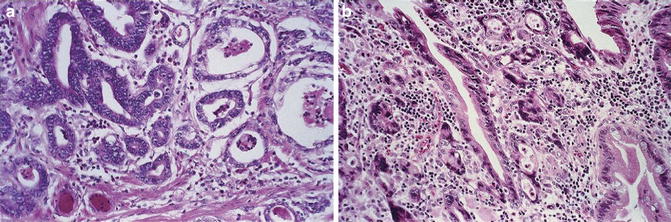

Fig. 7.3

Esophageal adenocarcinoma. Irregularly shaped and sized glands with serration. Lack of a rim of periglandular myofibroblasts (Surgical Pathology of the GI tract, Liver, Biliary Tract and Pancreas, Elsevier/Saunders, 2009 with permission)

Discussion

Esophageal adenocarcinomas are believed to follow the intestinal metaplasia–dysplasia–carcinoma pathway. The metaplastic glandular epithelium is lined by a layer of periglandular myofibroblastic cells which regulate many aspects of the epithelial cells like in the intestine (refer to the intestine section for more detailed discussion) [4]. Due to the presence of the periglandular myofibroblastic sheath, benign intestinal epithelial proliferations have a characteristic serrated appearance. Except for the rare serrated adenocarcinomas in the colon which possess other easily discernible characteristic features, genuine serration is rarely seen in gastrointestinal epithelial malignancies. This important feature can be very useful in the diagnosis of well-differentiated carcinomas where invasion is insidious and desmoplasia is not evident.

Corresponding to the lack of a serrated appearance in epithelial malignancies is the progressively decreasing presence of periglandular myofibroblastic cells along the spectrum of intestinal hyperplasia to dysplasia and adenocarcinoma [5, 6]. In the evaluation of periglandular myofibroblasts, the pathologist should be aware of a common phenomenon in Barrett’s esophagus: thickening of the muscularis mucosa and even the muscularis propria [7–9]. The hypertrophic muscle fibers can extend into the lamina propria or even form a new layer of muscular mucosa (duplication of muscularis mucosa). The upward extending muscle fibers, however, do not go around the glands in an accommodating fashion as the periglandular myofibroblasts. To help light up the periglandular myofibroblasts, immunostaining for SMA can be used. The other related issue is to avoid making an erroneous diagnosis of muscle invading adenocarcinoma when the hypertrophic muscle fibers are adjacent to benign or malignant glands in the lamina propria. Attention to the location of the hypertrophic muscle fibers is useful in this regard.

Differential Diagnosis

Benign or Dysplastic Glands Entrapped in Fibrotic Tissue

Fibrosis of the lamina propria and submucosa with entrapment of benign or even dysplastic glands is a common occurrence in metaplastic (Barrett’s) esophagus. The entrapped glands usually show cystic dilation and glandular serration. Periglandular myofibroblasts are appreciable.

In difficult cases, panel stains of CD44, E-cadherin, p53, and Ki67 should help in the distinction.

Esophageal Gland Duct Adenoma

Esophageal gland duct adenomas are well circumscribed and located in the submucosa [10]. They resemble their salivary counterpart, sialadenoma papilliferum, which contains a mixture of tubules, cysts, and papillary structures. A key feature is the presence of a two-cell-layer epithelium with the outer layer being myoepithelial cells.

Benign or Dysplastic Glands with Hyperplasia of Muscularis Mucosa

Attention to glandular serration and periglandular fibroblasts should point to the right direction.

Non-adenomatous-Type Dysplasia

While most Barrett’s-associated dysplasia present as a flat lesion with predominantly adenomatous (intestinal-type) histopathology, foveolar and serrated types of dysplasia may occur in the esophagus. The importance of recognition of these two uncommon types of dysplasia lies more in their associated clinical outcome than in differentiating them from well-differentiated adenocarcinomas since they have a serrated or foveolar appearance and presumably an extenuated layer of periglandular myofibroblasts. Even though they are cytologically bland, foveolar and serrated dysplasia are believed to have a natural history similar to the high-grade traditional adenomatous dysplasia [11, 12].

Pyloric Gland Adenoma

Rarely, pyloric gland adenomas are present in the esophagus. Barrett’s-associated dysplasia may also show a pyloric glandular phenotype. Recognizing their bland dysplastic features as well as their association with severe dysplasia or adenocarcinomas has important clinical significance as with the non-adenomatous dysplasia (refer to stomach section for more discussion).

Stomach

Key Morphological Features of Well-Differentiated Gastric Type Adenocarcinoma

Variation in glandular shapes and sizes in a non-foveolar/serrated and nonlobular pattern

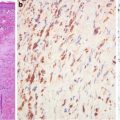

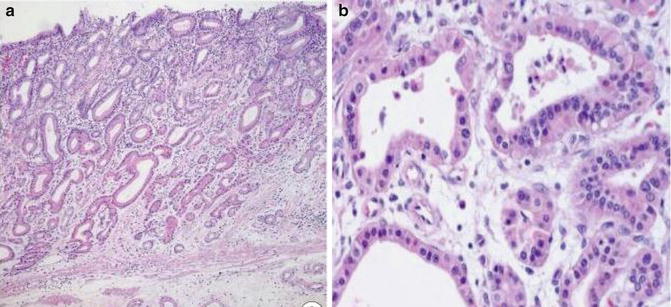

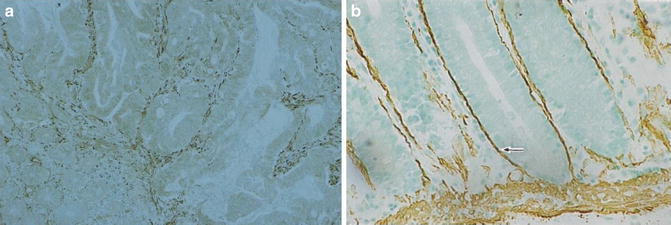

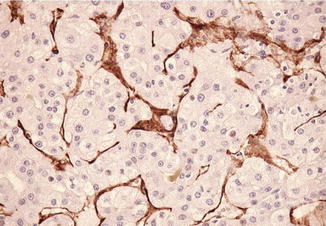

Lack of periglandular myofibroblasts (Fig. 7.4)

Fig. 7.4

Well-differentiated gastric-type adenocarcinoma. Note lack of periglandular myofibroblast (The Korean Journal of Pathology, Korean Society of Pathology, 2012 with permission)

Discussion

Most gastric adenocarcinomas resemble their esophageal counterparts in that they follow the same intestinal metaplasia to dysplasia to carcinoma pathway. Metaplastic glands also have a layer of periglandular myofibroblasts, and a similar progressively decreasing existence pattern for them exists along the metaplasia–dysplasia–carcinoma spectrum as in the intestine [13] (Figs. 7.5 and 7.6).

Fig. 7.5

Extremely well-differentiated gastric-type adenocarcinoma. Note deep penetrating irregular bland glands

Fig. 7.6

Gastric intestinal-type adenocarcinoma (Gut, BMJ Publishing Group, Ltd, 2005 with permission)

The fact that gastric foveolae, hyperplastic polyps, and adenomas share striking morphological similarities with their intestinal equivalents suggests that a similar type of periglandular myofibroblasts should be present around normal nonmetaplastic gastric glands. Our unpublished data indicate that this is the case even though it appears that the lower portions of glands have an attenuated layer of myofibroblast which surrounds several rather than individual glandular lumens. The rapidly proliferative upper portions have a sheath of periglandular myofibroblasts. This layer of myofibroblasts is supposed to play a vital role in the normal glandular morphogenesis and maintenance like their intestinal counterparts. Presumably, their presence in the upper portions of glands contributes to the foveolar appearance of normal and hyperplastic mucosa. This might explain why some benign gastric epithelial lesions such as oxyntic gland polyp/adenomas and pyloric gland adenomas do not have or have only a focal foveolar appearance. Fortunately, these two rare entities can be differentiated from well-differentiated adenocarcinomas by their overall lobular pattern and other cytological features.

Judicious use of the two morphological features is particularly useful in the distinction of well-differentiated gastric adenocarcinomas from most benign proliferations in small biopsy specimens where invasion is not obvious. In the evaluation of periglandular myofibroblasts, a strict criterion should be applied as in the esophagus and intestine. The spindle cells should closely embrace the contours of the corresponding glands to be considered periglandular myofibroblasts. This is to avoid mistaking tumor stromal myofibroblasts for periglandular myofibroblasts since the former can get close to the malignant glands. The tumor stromal cells, however, do not accommodate their arrangement to the shape of the glands and they lack a connection to the muscularis mucosa. Like in the Barrett’s esophagus, many benign gastric polyps and reactive lesions have a characteristic smooth muscle component in their lamina propria. These muscle fibers can be traced down to the muscularis mucosa [14]. They might get close to the benign glands; however, they do not show the characteristic embracing pattern. Instead, a perpendicular relationship to the mucosa can be appreciated. In the case of gastritis cystica polyposa/funda, the muscle fibers can be traced up to the muscularis mucosa, and due to their entrapped nature, they can become disorganized. Pancreatic heterotopia also has hypertrophic, disorganized smooth muscle fibers emanating from the muscularis mucosa. The disorganized bundles often mix with pancreatic acini and duct. The importance of appreciating the smooth muscle components and their presenting features lies mainly in avoiding a diagnosis of muscle invading adenocarcinoma especially when reactive changes are present in the epithelial component.

The so-called gastric-type well-differentiated adenocarcinomas have been slowly recognized, particularly in Europe and Japan [15]. They consist of cuboidal to columnar cells with mucinous cytoplasm. Characteristically, papillary and villous projections are prominent in the upper portion and irregularly branching and fusing glands are present in the middle and bottom portions of the tumor. This branching and fusion pattern has been interpreted as stromal invasion. In addition to the unique architectural feature, the tumor cells lack surface maturation and show cytological atypia (small nuclei with nucleoli, lack of apical mucinous cap).

A very small fraction of gastric adenocarcinomas are extremely well differentiated [16–18]. The gastric phenotype is easily confused with hyperplastic polyps or even normal gastric mucosa, whereas the intestinal phenotype is more likely mistaken for intestinal metaplasia. The presence of a foveolar appearance in some of the glands indicates that there probably exists at least partially operative interaction between the malignant epithelium and periglandular myofibroblasts. The tumor cells are generally benign looking, slowly proliferative, and p53 negative. However, the malignant nuclei are obviously larger and more hyperchromatic at least focally when comparison with the adjacent normal gastric mucosal cells is made. The only definitive sign of their malignancy is deep location and/or metastasis (Fig. 7.7). In the exercise of identifying deep invasion, we propose that attention be paid to the relationship of the beguilingly benign glands with the adjacent smooth muscle fibers as benign gastric polypoid lesions often contain prominent hypertrophic smooth muscle fibers. The invasive glands should be splitting the horizontally arranged smooth muscle fibers. An emanating relationship with the muscularis mucosa is nonexistent since the invaded fibers are part of the muscularis propria.

Fig. 7.7

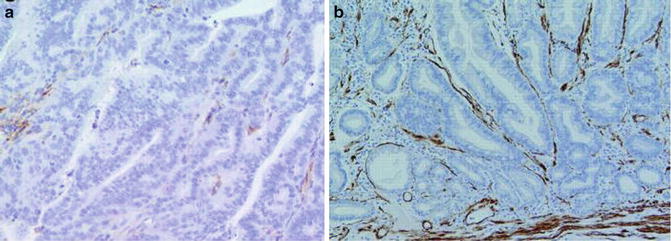

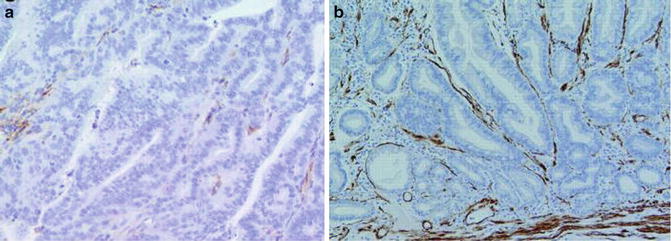

Gastric intestinal-type adenocarcinoma. Pericryptal fibroblasts are absent (a, alpha smooth muscle actin stain). Pericryptal fibroblasts are present in intestinal metaplastic glands (b)

Differential Diagnosis

Benign Lesions with Non-foveolar Appearance

Pancreatic Heterotopia

When pancreatic heterotopia is involved by acute and chronic pancreatitis with necrosis and fibrosis with a reactive overlying gastric mucosa, distinction from malignancy is in order. An overall lobulated appearance with squamous metaplasia of the ducts as well as hypertrophic smooth muscle fiber between glands and duct is an important diagnostic feature.

Intestinal-Type Adenoma

Low-grade intestinal-type adenomas can resemble well-differentiated adenocarcinoma both cytologically and architecturally. They, however, show periglandular myofibroblasts and lack desmoplasia.

Rare cases of intestinal-type adenoma with neuroendocrine cell proliferation can mimic invasive adenocarcinoma. The neuroendocrine cells appear to be budding off from angulated glands and infiltrating to the muscularis mucosa or submucosa. The neuroendocrine features of the cells are evident.

Brunner’s Gland Nodule

Submucosal Brunner’s gland nodule can be seen in the prepyloric region of the stomach. They are composed of benign-looking glands with a lobular arrangement and embraced with layer periglandular myofibroblasts.

Neuroendocrine Tumor

Gastric neuroendocrine tumors can show occasional rosette, tubule, and acinar structures. Attention to their cytological features as well as the presence of other typical growth patterns should help in the distinction.

Oxyntic Gland Polyp/Adenoma

Oxyntic gland polyp/adenomas are rare and present as a deep mucosal lesion with tightly packed irregular glands and anastomosing cords composed of chief cells with nuclear polymorphism and anisonucleosis [19]. They tumors have a low proliferative index corresponding to a benign prognosis. The presence of thin wisps of smooth muscle fibers can mimic a submucosal invading adenocarcinoma. Immunostaining for pepsinogen can help.

Benign Gastric Lesions with Foveolar or Partially Foveolar Morphology

Foveolar Hyperplasia and Dysplasia

Foveolar hyperplasia contains tightly packed foveolar glandular components which can be affected by regenerative atypia (mucin depletion, hyperchromasia, prominent nucleoli, and mitotic figures). The regenerative atypia should be differentiated from foveolar-type dysplasia (adenoma) which lacks stratification [20, 21]. Regenerative atypia, however, usually begins halfway within the gastric mucosa and then extends to the surface with sparing of the bottom portion. Therefore, a full thickness mucosal atypia remains the most reliable criterion for foveolar-type dysplasia. Of course, the presence of active inflammation favors the former.

When accompanied by upward extending smooth muscle fibers, they can be confused with invasive carcinoma. The presence of a foveolar appearance and periglandular myofibroblasts helps make the distinction. In difficult cases, a panel of immunostainings for p53, Ki67, CD44, and LgL2 could be used.

Gastritis Cystic Polyposa/Profunda

Exuberant proliferation of benign mucosa entrapped in deep portions of the gastric wall can resemble invasive adenocarcinoma [14, 22]. Important distinguishing features include a rim of normal lamina propria with an intact myofibroblast layer, foveolar glands arranged in a lobular pattern, and stromal changes such as inflammation, hemorrhage, and fibrosis. The overlying mucosa always shows hyperplastic changes.

Hyperplastic Polyp, Peutz–Jeghers Polyp, Juvenile Polyp, Cronkhite–Canada Syndrome Associated Polyp

All polyps under this heading have a characteristic foveolar component. Except for Cronkhite–Canada syndrome-associated polyps which usually show no prominent muscle proliferation, all the other types have associated muscular proliferation and inflammatory lamina propria.

Nevertheless, the presence of a foveolar-type proliferation does automatically rule out malignancy as dysplasia, and invasive adenocarcinoma can arise from such benign milieu. The intestinal type of dysplasia has the classic nuclear elongation, pseudostratification, and hyperchromasia. As discussed previously, awareness of the criterion for foveolar-type dysplasia is necessary in its distinction from regenerative reactive changes [20, 21]. An invasive component lacks foveolar formation and periglandular myofibroblasts. Other features of malignancy include haphazard glands with greater variation in shape and size, sometimes desmoplasia.

Fundic Gland Polyp

Characteristic morphological features of fundic gland polyps include irregular glands with cystic dilation, budding, flattening of cyst lining cells, as well as presence of chief and parietal cells. The surface and foveolar epithelium can show both hypertrophic and atrophic changes. Because of their small size, well circumscription, and morphological features, distinction from invasive carcinomas is usually straightforward. The issue lies mainly in the distinction between reactive changes and true dysplasia which might involve the surface and foveolar epithelium.

Pyloric Gland Adenoma

This often underappreciated entity contains closely packed glands composed of a monolayer of cuboidal to low columnar epithelial cells with ground cytoplasm, but no mucin cap [15, 23]. Occasional foveola-like structures and cellular blandness and minimally stratified nuclei make it more likely to be mistaken for gastric hyperplastic polyps than for gastric carcinomas. The distinction from the former is, however, clinically significant since 20–30 % of them have been reported to progress to severe dysplasia and/or adenocarcinomas. Furthermore, pyloric adenomas contain p53 positivity and similar chromosomal abnormalities to those of gastric-type adenocarcinomas. Attention to the lack of an apical mucin cap and positivity for both MUC5AC and MUC6 should help clinch the diagnosis.

Colorectum

Key Morphological Features of Well-Differentiated Colorectal Adenocarcinoma

Glandular proliferation with non-serrated appearance

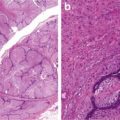

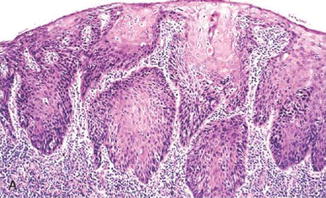

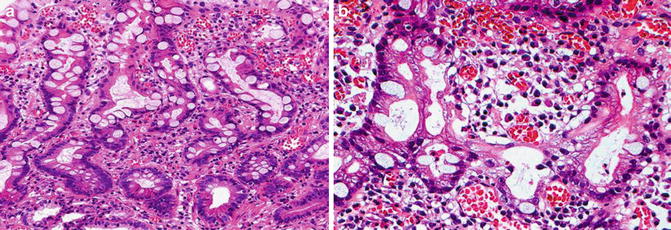

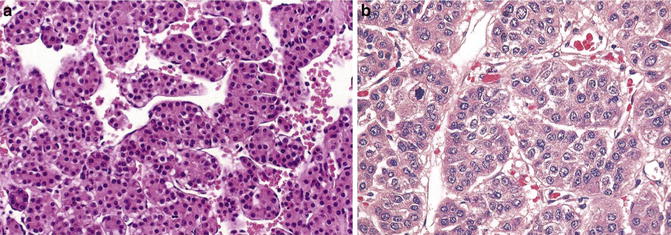

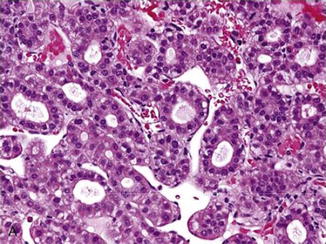

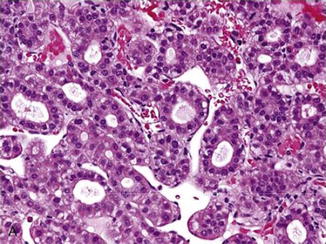

Absence of pericryptal myofibroblasts (Figs. 7.8 and 7.9)

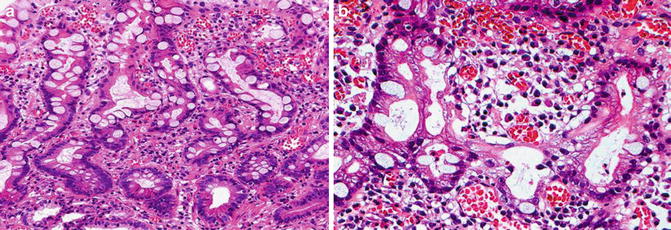

Fig. 7.8

Well-differentiated colonic adenocarcinoma

Fig. 7.9

Well- to moderately differentiated colonic adenocarcinoma. Lack of pericryptal myofibroblasts (alpha smooth muscle actin stain) (Surgical Pathology of the GI tract, Liver, Biliary Tract and Pancreas, Elsevier/Saunders, 2009 with permission)

Discussion

Well-differentiated colorectal adenocarcinomas are characterized by predominantly well-formed glands with smooth and regular lumens. Except for the rare entity of serrated adenocarcinoma which has its characteristic cytological and architectural features, genuine serration is lacking in colorectal adenocarcinomas. Serrations are not to be confused with papillations or pseudo-serrations in necrotic complex tubular or cribriform structures. They should contain epithelial tufts composed of only epithelium or epithelium and basement membrane material [24].

The serrated appearance of benign colorectal proliferations is believed to result from a decreased apoptosis/proliferation ratio and delayed cell migration which still follows the normal bottom to surface route [25–27]. Whereas the pericryptal fibroblasts might very well provide some trophic factors for the epithelial growth, their physical presence along with the basement membrane as a component of a complex framework constitutes a powerful restraining force in preventing a full-blown expansion of the crypts and stratification.

The pericryptal fibroblastic sheath in the intestinal tract is a unique syncytium of specialized fibroblasts which extend laterally into the lamina propria to connect with other fibroblasts and downward to associate with the muscularis mucosa [6, 28–32]. Through gap and tight adherence, they are even connected to the overlying epithelial cells. Thus, formed complex network provides the framework for the normal cryptal formation, maintenance, and function. In fact, not only are they a very important component of the stem cell niche located at the bottom of the crypts; the pericryptal fibroblasts also play an essential role in the proliferation, maturation, and upward migration of the epithelial cells. Furthermore, this epithelial–mesenchymal (pericryptal fibroblast) interaction appears to be bidirectional [33]. An excellent example in highlighting this interactive nature is the so-called perineuroma-like proliferation in which the pericryptal fibroblasts are believed to undergo perineural differentiation and demonstrate their characteristic pericryptal whirling growth pattern. Some focal perineuroma-like proliferations are associated with sessile serrated adenomas.

The pericryptal fibroblasts are likely to play an important role in intestinal epithelial tumorigenesis. For instance, pericryptal fibroblasts of colorectal adenomas express high concentrations of cyclooxygenase (COX-2) [34]. Disturbance in their cell adhesion molecule expression has been associated with concurrent neoplasia in patients with ulcerative colitis [35]. More importantly, corresponding to the colorectal hyperplasia–dysplasia–carcinoma spectrum is the progressively decreasing presence of the pericryptal fibroblasts with absence or rarity of pericryptal fibroblast around carcinomatous glands [28, 36, 37]. While it is still premature to conjecture how changes in the pericryptal fibroblasts contribute to epithelial tumorigenesis, the following statement holds true: this is total disruption of a healthy, harmonious nature of the epithelial–mesenchymal interaction with resultant absence or rarity of pericryptal fibroblasts around malignant glands. The diagnostic importance of this observation is analogous to that of the absence of basal cells in prostatic adenocarcinomas and lack of myoepithelial cells in mammary malignancies. It would prove to be very helpful in surgical pathology sign-outs (particularly small biopsies) when other signs of malignancy are not salient.

The nature of dysplasia in serrated lesion differs significantly from that of the conventional adenomas in that apoptosis is largely inhibited and the increased proliferative activity is still restricted to the lower portion of the crypt [25, 26]. Presumably, the epithelial–mesenchymal interaction in serrated adenomas and even serrated adenocarcinomas is better preserved than in their conventional counterparts. The serrated neoplastic cells have a low nuclear/cytoplasmic ratio with preservation of cell polarity and abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm, and they still retain their cell-to-cell adhesion with stratification restricted largely to the tufted areas [25, 26, 38]. This is in contrast to the conventional adenomas where proliferation activity is no longer restricted to the crypt bottom. Instead, they manifest a diffuse, top heavy proliferation pattern. We speculated that a change (disturbance of cell adhesion molecules) similar to that of ulcerative colitis associated pericryptal fibroblasts might happen here, allowing for epithelial stratification and loss of polarity.

It is believed that serrated adenocarcinoma occurs as a result of loss of inhibition on the apoptotic pathways [25–27, 39]. Published diagnostic criteria for differentiating it from non-serrated adenocarcinomas include serrated morphology, mucinous differentiation, eosinophilic cytoplasm, vesicular nuclei, and absence of dirty necrosis. In well-differentiated serrated adenocarcinomas, genuine serration with well-polarized cells is evident. However, information is lacking on the status of periglandular fibroblasts in serrated tumors.

As in the evaluation of gastric and esophageal periglandular fibroblasts, strict criteria must be followed so that tumor stromal myofibroblasts and hypertrophic smooth muscle fibers are not confused for pericryptal fibroblasts. The spindle cells should closely embrace the contours of the corresponding glands/crypts, and a connection to the muscularis mucosa is usually possible.

Finally, a small fraction of inflammatory bowel disease-associated colorectal adenocarcinomas present as the so-called very well-differentiated adenocarcinoma (low-grade tubuloglandular adenocarcinoma) of the colon [40]. They are composed of cells with low-grade nuclei. Some of the glands have round or tubular profiles, while some have branching glands. They lack both serration and pericryptal fibroblasts.

Differential Diagnosis

Adenoma with Pseudoinvasion

Importantly, these misplaced epithelial cells are usually surrounded by a rim of lamina propria (with pericryptal sheath fibroblasts) and have a well-circumscribed or lobular overall appearance [41]. Cytologically, they are similar to their mucosal counterparts with which communication can sometimes be found. The adjacent stroma usually contains hemorrhage or hemosiderin. When mucin pools are present, they lack the features of malignant mucin (irregular, dissecting pools with floating malignant cells).

Colitis Cystica Polyposa/Profunda

The benign herniated or misplaced glands often present as well-circumscribed lobules. Presence of a rim of lamina propria (with pericryptal fibroblast) can be found. Evidence of previous injury is often discernible.

Sessile Serrated Adenoma

They are characterized by irregular crypts with a dilated base which might extend laterally in parallel to the muscularis mucosa. Sometimes, the crypts can be herniated through the muscularis mucosa, giving the erroneous impression of invasive adenocarcinoma. The telltale signs are serration and maturation at the base of the crypts.

Benign Polyp

Hyperplastic polyps are rarely confused with well-differentiated adenocarcinomas because of their small size and characteristic serration. Inflammatory or hamartomatous polyps can reach a bigger size, and serration is sometimes not prominent. Furthermore, strands of smooth muscle cells can be present next to benign glands, and misplacement of epithelial cells into deeper structures can occur. Attention to the presence of a rim of benign lamina propria (with intact pericryptal fibroblasts) can be very helpful in ruling out invasive carcinoma.

The Small Intestine and Periampullary Region

The vast majority of adenocarcinomas in the small intestine and periampullary area are almost identical to colorectal carcinomas and can be evaluated as such. The so-called pancreatobiliary type makes up less than 20 % of the adenocarcinomas in the periampullary region and is mostly well differentiated. Morphologically they conform to their pancreatic ductal and extrahepatic biliary counterparts and therefore are subjected to their criteria (nonlobular arrangement of glands and tubules, prominent desmoplasia around individual glands).

Differential Diagnosis for Small Intestine Adenocarcinoma

Brunner’s Gland Hyperplasia and Hamartoma

Their benignity is usually manifested in lobulation and cellular blandness. The benign glands might extend into the lamina propria and even become pedunculated with resultant hyperplastic fibromuscular stroma and adipose tissue, thus creating an invasive appearance. However, de novo dysplasia and carcinomas of the glands remain to be documented. Instead, rare reported cases of adenoma and adenocarcinoma actually represent secondary involvement by the surface dysplasia or adenocarcinoma. The involved glands remain lobular and presence of periglandular fibroblasts is discernible.

Neuroendocrine Tumor with Acinar Growth Pattern

Duodenal neuroendocrine tumors usually show gland-like formations which can contain secretions. Attention to the cytological features and the lack of true glandular lumens allows for their distinction from well-differentiated adeno-carcinoma.

Pancreatic Heterotopia

When involved by regenerative atypia, pancreatic heterotopia might simulate invasive carcinoma. However, its lobulation and lack of desmoplasia give it away.

Gastric Heterotopia with Secondary Mucosal Prolapse

It contains tightly packed benign glands composed of chief and parietal cells with surface epithelial (foveolar) hyperplasia. When pedunculated, arborizing bundles of smooth muscle fibers can be traced to the hyperplastic muscularis mucosa. It is not to be confused with muscle invading adenocarcinoma.

Colitis Cystica Profunda, Misplacement of Adenomatous Epithelium

The misplaced benign epithelium in the submucosal or muscularis can imitate well-differentiated adenocarcinoma. As in colitis cystica polyposa/profunda, the benign glands are well-circumscribed lobules. The presence of a rim of lamina propria (with pericryptal fibroblasts) can be identified.

Differential Diagnosis for Periampullary Adenocarcinoma

Ampullary Adenoma Involving Periampullary Glands

Due to the enmeshment of the periampullary ducts and glands with smooth fibers, a perfect picture of invasive adenocarcinoma is created when adenomatous cells of the ampulla extend into the adjacent glands. Attention to the lobular feature and similar nuclear features as those of the surface adenomatous component should point in the right direction. Moreover, the involved ducts and glands do not elicit desmoplasia.

Colonization of Mucosal Basement Membrane by Underlying Well-Differentiated Invasive Pancreatic or Biliary Duct Adenocarcinoma

The significance of this entity lies mainly in its distinction from primary ampullary adenomas. Instead of having irregular glands with abundant desmoplasia, it closely resembles a primary adenoma. In difficult cases, immunostainings are needed. These adenoma-like cells are positive for CK7 and MUC1 and negative for CDX2 and MUC2.

Paraduodenal Pancreatitis

When located in deeper locations, the pancreatic tissue is usually surrounded by hypertrophic smooth muscle fibers and fibrosis. Differentiation from pancreatobiliary-type adenocarcinomas requires appreciation of a lobular configuration and lack of desmoplasia.

Liver

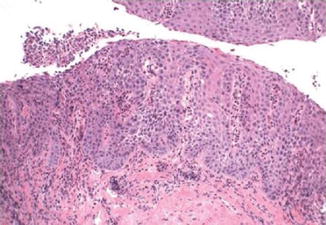

Key Morphological Features of Well-Differentiated Hepatocellular Carcinoma

Thick cords with higher cell density (equal or greater than three-cell thick) and or reduced reticulin reduction

Capillarization of sinusoids (diffuse CD34 positivity) (Figs.7.10, 7.11, and 7.12)

Fig. 7.10

Well-differentiated hepatocellular cell carcinoma. Note thick cords with endothelial wrapping (Atlas of Liver Pathology, Elsevier/Saunders, 2011 with permission)

Fig. 7.11

Well-differentiated hepatocellular cell carcinoma. Thick cords are highlighted with reticulin stain (Atlas of Liver Pathology, Elsevier/Saunders, 2011 with permission)

Fig. 7.12

Well-differentiated hepatocellular cell carcinoma. Capillarization of sinusoids is demonstrated by CD31 reactivity of the wrapping endothelial cells (Atlas of Liver Pathology, Elsevier/Saunders, 2011 with permission)

Discussion

The normal adult hepatic tissue is ideally crafted for optimal substance transport between the circulation, bile canaliculi, and hepatocytes. The hepatic cords are normally one-cell layer thick with sinusoid vessels lining on each side. Two-cell thick plates and even rosette formations are visible only in regenerative conditions. The normal hepatic structure is maintained by a delicate network of reticulin lining the hepatic sinusoids as a result of normal epithelial–mesenchymal (stellate cells) interaction [42, 43]. Importantly other fibrogenic activity of the organ is kept to the minimum in the functional units with visible fibrous tissue limited to the portal tracts, bile duct and accompanying vascular bundles, and the capsule.

Fig. 7.13

Well-differentiated hepatocellular cell carcinoma, pseudoglandular variant. Note endothelial wrapping and lack of desmoplastic stroma (Atlas of Liver Pathology, Elsevier/Saunders, 2011 with permission)

In most hepatocellular carcinomas, the antifibrogenic feature of the hepatoblasts is largely conserved (Fig. 7.13). While reticulin production is still operational or even increased, it seems to be outstripped by the rapidly proliferating tumor cells [43, 44]. Thus [44], thick cords (three or more cells across) lined by attenuated reticulin fibers become evident. This important feature can be appreciated even in the rare fibrolamellar and scirrhous variants in which abundant fibrotic tissue is present. The increased fibrogenic activity in these two variants indicate their cholangiolar differentiation (fibrolamellar variant cells: positive for CK7, EMA, and Hepar1; cirrhotic variant cells: negative for Hepar1 and positive for CK7) [45–49]. The pseudoglandular variant can also be viewed as having thickened plates if one can mentally cut the lumen open and spread the cells out. The normal canaliculi are lined by only two to three hepatocytes, and when spread out, the cords are no more than three cells thick. The imaginary cords in hepatocellular carcinomas seem to be more cellular and more diffuse than those derived from rosettes in hepatic adenomas and hepatitis.

In evaluating reticulin stain, it is important to pick areas uncompromised by steatosis. It is known that steatosis can impair the production of reticulin to an extent comparable to that of the hepatocellular carcinoma [50]. Moreover, hepatocellular carcinomatous cells can have steatotic changes.

Another important feature of hepatocellular carcinomatous cells is that they maintain the capability to induce brisk angiogenesis and obtain abundant blood supply like their hepatoblast counterparts [51–53]. The difference is, however, that the former tend to derive their nutrients from the arterioles, while the latter is supplied by both portal veins and arterioles. Thus, the tumor microvessels are subjected to higher perfusion pressures leading to capillarization. The normal sinusoids are negative for CD34 and CD31. Capillarized microvessels become positive for the two markers. This important feature has also been employed widely in the daily surgical pathology sign-out.

In the utility of both the reticulin and CD34/CD31 stains for the differentiation of hepatic nodules, it is advisable that they are considered in tandem. Rare cases of hepatocellular carcinoma with increased reticulin production have been reported and the increased reticulin production presents in the form of monolayer trabecular pattern [44]. Disturbance in the blood supply is common in benign hepatic nodules, and focal capillarization of the microvessels can occur. When the two stains seem to conflict with each other, careful attention to the distribution of CD34/CD31 positivity and finding a non-steatotic area can be very helpful. For instance, in cirrhotic nodule, the CD34/CD31 positivity is largely restricted to the periphery while focal nodular hyperplasia has its positivity near the fibrous septa [54, 55]. Variable staining patterns have been reported for hepatic adenomas. However, they have intact or only focally reduced reticulin framework with cords less than three cells across [54, 55].

Differentia Diagnosis

Macroregenerative Nodules, Dysplastic Nodule, and Early Hepatocellular Carcinoma

Large regenerative nodules measure 0.8 cm or greater and have intact reticulin framework with cell plates no more than two-cell thick. CD34 or CD31 stain may show some peripheral staining and reveal some unpaired arterioles. When large cell dysplasia or small cell dysplasia occur, a dysplastic nodule is formed.

Early hepatocellular carcinomas have been increasingly evaluated by surgical pathologists. Defined as nodules less than 2 cm in diameter, they lack a tumor capsule and grow by replacing the existing hepatocyte cords [56–58]. Stromal invasion with various numbers of portal tracts can be present within the nodule. The reticulin framework is usually reduced but not totally lost. Increased CD34 sinusoidal staining and unpaired arterioles are present.

Focal Nodular Hyperplasia

This lesion contains cell plates of normal or slightly increased thickness with sinusoidal vessels. It can show CD34-/Cd31-positive microvessels which are adjacent to the fibrous septa. Other diagnostic features include a central fibrous area connecting with multiple well-circumscribed nodules. The central area contains large arterial vessels with no accompanying large bile ducts and portal veins.

Nodular Regenerative Hyperplasia

Nodular regenerative hyperplasia contains small nodules with minimal fibrous septation. Its cell plates are less than two cells thick and areas of atrophy with reticulin condensation are common between the nodules. The sinusoids might be arterialized; therefore, focal CD34 positivity can be seen.

Hepatic Adenoma

Hepatic adenomas can have thickened plates, but their thickness is usually less than 3 cells across. Reticulin stain reveals intact or only focally reduced reticulin staining. Diffuse CD34 positivity has been reported in some cases; however, majority of cases show negativity or focal positivity.

The tumors usually lack a capsule and occur as a result of oral contraceptive or anabolic steroid use or other metabolic disorders. This is in contrast to classical hepatocellular carcinomas which develop largely in cirrhotic liver and rarely arise from hepatic adenomas. In difficult cases, immunostainings for glypican-3 and AFP can be applied to make the distinction.

Epithelioid Angiomyolipoma

Hepatic angiomyolipomas usually contain a scant fat component. Problems might arise when the tumor cells show trabecular formation with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm. However, spider web-like cytoplasm and presence of thick-walled vessel should arouse doubt about a hepatocellular carcinoma. Immunostainings for HMB45 and smooth muscle actin light up the tumor cells.

Pancreas

Key Morphological Features of Well-Differentiated Ductal Adenocarcinoma

Nonlobular arrangement of glands and tubules

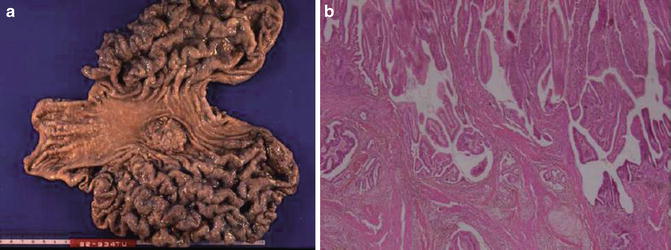

Prominent desmoplasia around individual glands (Figs. 7.14)

Fig. 7.14

Well-differentiated pancreatic ductal carcinoma. Note nonlobular arrangement of irregular glands and prominent desmoplasia (Surgical Pathology of the GI tract, Liver, Biliary Tract and Pancreas, Elsevier/Saunders, 2009 with permission)

Discussion

The pancreatic exocrine morphogenesis/organogenesis follows the classic paradigm for glandular formation with a resultant lobular appearance. In chronic pancreatitis, the most common mimicker of well-differentiated ductal adenocarcinomas, this lobular pattern is still largely preserved even though the benign ducts are often atrophic and deprived of acinar structures. In contrast, carcinomatous glands are nonlobular and randomly distributed.

Reviewing this vital organ of the human body, one would not help but wonder at the ingenuity of Mother Nature in devising various safety mechanisms in order to prevent and limit the dreadful event of activating or leaking destructive digestive enzymes to adjacent tissues or organs. First of all, rather than obtaining its blood flow from a single source, the pancreas derives its arterial supply from rich anastomoses around the organ with many contributing components [59, 60]. Second, benign pancreatic ductal structures containing digestive enzymes are structurally separated from muscular vessels and are surrounded by acini and fibrous tissue [61, 62]. In doing so, the risk of lethal hemorrhage due to corrosion into the large arteries by digestive enzymes is reduced. This vessel shunning property of ductal epithelium has been illustrated by developmental biology research showing that early endothelial cells are essential for the onset of pancreatic budding and endocrine specification, but later on they inhibit further branching and exocrine differentiation [63–66].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree