INTRODUCTION

Gastric polyps are typically found incidentally during upper endoscopy performed for unrelated reasons, as most do not cause clinical symptoms or signs. They are found in about 4% of upper endoscopic procedures, and the relative frequency of each type depends on several factors, including the prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection. Gastric polyps, once detected, may have significant clinical implications, and accurate histopathologic diagnosis is of paramount importance to ensure proper management. This chapter reviews the clinical and pathologic characteristics of both common and uncommon gastric polyps. In addition to the pathologic features of gastric polyps themselves, substantial information about their etiology can be gleaned from the evaluation of the unaffected gastric mucosa and is briefly discussed. Although most gastroenterologists are aware of this fact, in our experience proper sampling of adjacent mucosa is uncommonly performed at the time of polypectomy.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Published data on the epidemiology of gastric polyps diverge substantially with regard to both absolute and relative prevalence, largely due to variations in the population studied, including age, gender, the prevalence of underlying gastric conditions, the detection methodology used, and the accuracy of the pathologic diagnosis. In general, pathology-based series, in which the denominator is the total of gastric biopsies sampled, are useful to determine the relative frequency of the various types of polyps.

1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 and 10 Regarding prevalence, retrospective reviews of endoscopic reports are likely to underestimate the true rates, because all polyps are typically not excised and characterized,

11,12 while prospective evaluations are necessarily limited to relatively small numbers of patients in single institutions, with resulting population and expertise biases. These pitfalls must be kept in mind when interpreting the prevalence data in

Table 21-1.

A diverse array of polyps and polypoid lesions may be found in the stomach. Polyps may be epithelial (e.g., fundic gland, adenomatous), neuroendocrine (e.g., carcinoid), lymphohistiocytic (e.g., xanthelasma, lymphoid hyperplasia), mesenchymal (e.g., gastrointestinal [GI] stromal, neural, vascular), or mixed. Some are sporadic and some syndromic. This review excludes carcinomas, lymphomas, carcinoids, mesenchymal tumors, and all other malignancies, which are discussed in other chapters.

FUNDIC GLAND POLYPS

Fundic gland polyps (FGPs) are the most common type of polyps detected at Esophago-gastrodvodenoscopy (EGD) in Western countries (up to 50%),

13 apparently due to the relatively low incidence of

H. pylori infection and relatively high level of proton pump inhibitor (PPI) use.

1 In fact, FGPs are negatively associated with

H. pylori infection.

13, 14, 15 and 16 This negative association is further, if indirectly, supported by reports of the disappearance of FGPs upon

H. pylori infection and their subsequent recurrence after eradication.

17The reported prevalence of FGPs ranges from 3.2% to 11%.

18, 19 and 20 While most FGPs are sporadic, they were originally described in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) syndrome.

21, 22 and 23 Sporadic FGPs are most prevalent among middle-aged women,

13,15,19 although this gender difference is not observed in all studies. Among FAP patients, the prevalence of FGPs is much higher than in the general population, occurs at a younger age, and is equally likely to develop in both genders.

13,22Endoscopically, FGPs appear as smooth, glassy, sessile, circumscribed elevations in the oxyntic mucosa, usually measuring <0.5 cm. Sporadic polyps are typically single or few; however, in PPI users, there may be large numbers of polyps, although these may regress with cessation of therapy.

24 In contrast, syndromic patients may have 50 polyps or more, sometimes becoming confluent and measuring as large as 5 to 8 cm (“giant FGPs”).

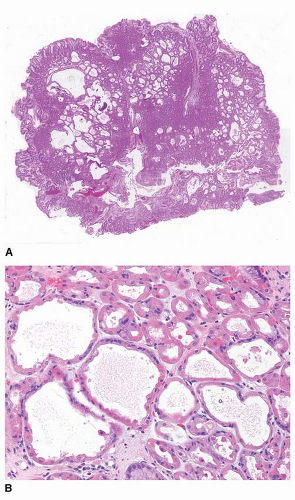

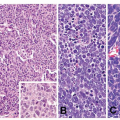

25Histologically, FGPs comprise cystically dilated oxyntic glands, with the lining cells appearing variably flattened or hobnail-like (

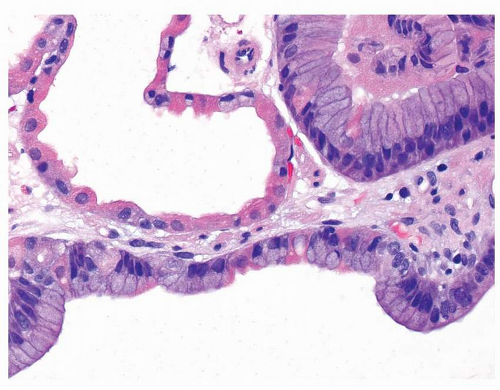

Fig. 21-1A and B). These lining cells may become difficult to recognize as oxyntic when markedly dilated (

Fig. 21-2). While dysplasia is frequent in FAP patients with FGPs (up to half), almost all are low-grade.

21,22 In sporadic cases, true dysplasia is very unusual, and high-grade dysplasia is distinctly rare.

26 Given the extreme rarity of advanced gastric neoplasia in patients with FGPs, we recommend being very conservative in the interpretation of focal nuclear enlargement of the pit epithelium that occasionally occurs in FGPs and is likely not biologically true dysplasia. Nevertheless, when multiple FGPs are diagnosed in a young patient and when true dysplasia is encountered, FAP should be considered, and it is incumbent upon the pathologist to alert the clinician about this possibility.

Little is known about the etiology of FGPs. In the past, these polyps were considered to be hamartomatous; however, the recently recognized association of FGPs with long-term use of PPIs suggests that mechanisms related to the suppression of acid secretion may be involved in their pathogenesis.

27 In recent years, there has been somewhat conflicting evidence of genetic alterations in sporadic and syndromic FGPs that are intriguing but do little to further our understanding of pathogenesis or enhance our ability to discern these two pathogenic types. For example, the Wnt signaling pathway is implicated in both syndromic and sporadic FGPs. Also, up to 75% of patients with FAP-associated polyps demonstrate a somatic second-hit mutation of the

APC gene that leads to the inactivation of both copies of this tumor suppressor gene and occurs independently of the presence of histologic dysplasia.

28, 29 and 30 While most sporadic FGPs are devoid of APC mutations and 65% to 90% harbor somatic mutations in the b-catenin gene,

28, 29 and 30 rare cases of sporadic dysplastic FGP have been shown to demonstrate APC mutations without b-catenin mutations.

28,31 In addition, methylation of promoters of genes associated with gastric cancer has been observed in a small proportion of FGPs and mainly affects the promoters of the p16 and p14 genes.

32 Finally, tuberin has been hypothesized to play a role in the pathogenesis of sporadic FGPs with loss of tuberin nuclear expression and its cytoplasmic accumulation associated with loss of negative regulation of nuclear glucocorticoid receptors.

33For the typical patient on PPI therapy with multiple small (<0.5 cm) FGPs, a biopsy of one polyp should suffice to confirm the diagnosis. Biopsy specimens should be taken from all polyps ranging from 0.5 to 1 cm. It is not recommended to discontinue PPI therapy for these patients with smaller polyps. Larger polyps (>1 cm) should also be removed, and PPI therapy discontinued in these patients, if clinically appropriate.

Since some studies have suggested that FGPs are associated with a higher frequency of colonic adenoma, some authors have recommended that a colonoscopy be performed when FGPs are diagnosed.

19,34, 35 and 36 However, a recent study by Genta et al. of over 100,000 patients with simultaneous EGD and colonoscopy, >6,000 of whom had FGPs, found that there was no relationship between the presence of sporadic FGPs and neoplasia elsewhere in the GI tract. They concluded that the detection of sporadic FGPs does not warrant the performance of a colonoscopy.

13

HYPERPLASTIC POLYPS

Hyperplastic polyps are traditionally believed to arise most frequently in patients with an inflamed or atrophic gastric mucosa.

37 In the industrialized world, both their absolute and relative prevalence has been decreasing along with the declining prevalence of

H. pylori infection.

38,39 In a review of almost 8,000 gastric polyps examined over a 1-year period, only 14.3% were hyperplastic.

1 Solid organ transplantation has also been reported as a risk factor, with as many as 15% of hyperplastic polyps arising in transplant patients.

40,41 Hyperplastic polyps usually arise in adults (mean age: 60 years), and in most studies, a female predominance is reported, although others report an equal sex ratio or even a male predominance.

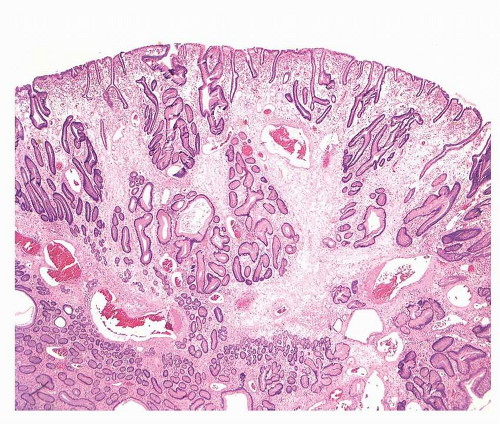

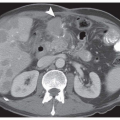

12,42,43Hyperplastic polyps are multiple in about 20% of the patients and are more frequently observed in the antrum. They are usually small (0.5-1.5 cm) with a smooth, dome shape, but they may grow much larger, becoming lobulated and pedunculated, some with surface erosions (

Fig. 21-3).

42,44 Protracted erosion may result in chronic blood loss and iron-deficiency anemia, one of the most common clinical manifestations of these polyps. Gastric outlet obstruction has also been described for large antral polyps that protrude into the duodenal lumen.

45,46 Nevertheless, most hyperplastic polyps remain asymptomatic.

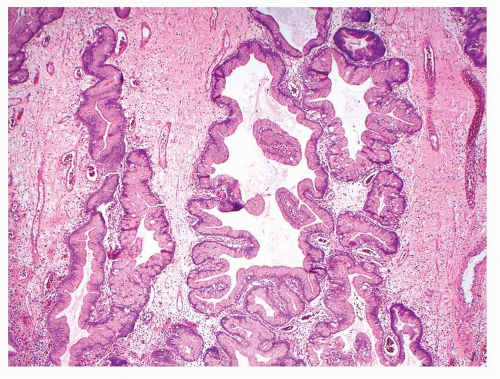

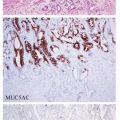

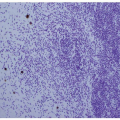

Hyperplastic gastric polyps comprise both epithelial and stromal components in varying proportions. There are elongated, grossly distorted, branching and dilated foveolae lying in an edematous stroma rich in vasculature and sparse, haphazardly distributed smooth muscle bundles along with a variable degree of chronic and active inflammatory cells (

Fig. 21-4). The epithelial lining consists of a single layer of regularly arranged hypertrophic foveolar epithelium containing abundant neutral mucin. In some regions, the cells may be cuboidal with a granular eosinophilic cytoplasm.

47,48 Parietal and chief cells are uncommon, even in polyps from the corpus. Intestinal metaplasia may be seen but is rarely a conspicuous feature. At the smaller end of the spectrum, it may be difficult to distinguish exuberant reactive gastropathy (i.e., “polypoid foveolar hyperplasia”) from a small hyperplastic gastric polyp; the latter term may be best used

when the endoscopist identifies a discrete polypoid lesion. Finally, other hamartomatous polyps (see below) can be histologically indistinguishable from hyperplastic gastric polyps and can be discerned only in the proper clinical context.