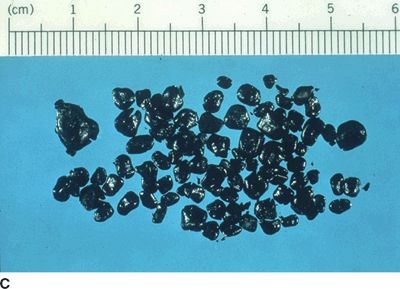

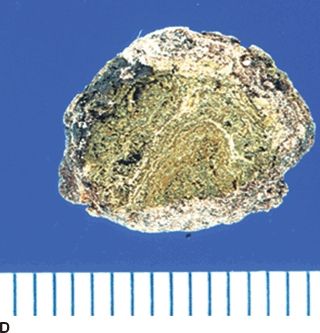

FIGURE 23.1 A. Pure cholesterol gallstones. B. Cholesterol gallstones with calcium. C. Black pigment stones. D. Brown pigment stones.

The gallbladder is a very effective absorptive organ, and a normal function of the gallbladder is to concentrate and acidify bile. For many years, three factors have been thought to be key in cholesterol gallstone pathogenesis: cholesterol supersaturation, cholesterol crystallization, and biliary motility. However, a fourth factor, gallbladder absorption/secretion, also is key to gallstone formation. Alterations in sodium, chloride, bicarbonate, and water absorption/secretion alter the milieu for both cholesterol crystal formation and for calcium precipitation with various anions (Fig. 23.1B).

Pigment Gallstones

Precipitation of calcium with bilirubin, carbonate, phosphate, or palmitate as insoluble calcium salts serves as a nidus for cholesterol stone formation. Furthermore, calcium bilirubinate and calcium palmitate also form major components of pigment gallstones. Pigment gallstones are classified as either black or brown pigment stones. Black pigment stones are typically tarry and frequently are associated with hemolytic conditions or cirrhosis (Fig. 23.1C). In hemolytic states, the bilirubin load and concentration of unconjugated bilirubin increases. These stones usually are not associated with infected bile and are located almost exclusively in the gallbladder.

In contrast to black pigment stones, brown pigment stones are earthy in texture and are typically found in the bile ducts, especially in Asian populations (Fig. 23.1D). Brown stones often contain more cholesterol and calcium palmitate than black stones and occur as primary common duct stones in Western patients with disorders of biliary motility and associated bacterial infection. In these settings, bacteria producing slime and bacteria containing the enzyme glucuronidase cause enzymatic hydrolysis of soluble conjugated bilirubin glucuronide to form free bilirubin, which then precipitates with calcium.

Prevalence

Gallstones are uncommon in patients younger than age 20 years, but a sharp increase is noted, especially in women, with each decade to approximately 70 years. Approximately 20% of women and 10% of Western men have stones by age 60 years. In certain populations, such as Native Americans, the incidence is extremely high, especially in women. In Chileans and Bolivians of Indian ancestry, gallstones also are very common, and they are associated with a high incidence of gallbladder cancer. In the United States, the prevalence of stones is highest in Mexican American women (26%), and the prevalence in white women (17%) is higher than in black women (14%).

Risk Factors

Gallstones are more common in women, especially those who are obese, have had multiple pregnancies, are taking birth control pills, are undergoing rapid weight loss, or have elevated serum triglyceride levels. Diet plays an important role in cholesterol supersaturation, and these gallstones do not form in vegetarians. Cholesterol gallstones are common in populations consuming a Western diet, which is relatively high in overall calories as well as animal fats and carbohydrates. Diabetic patients also have an increased incidence of gallstones, which may be caused, in part, by alterations in gallbladder motor function and/or absorption/secretion. Gallstones also are known to occur more frequently in certain families. Current theory suggests that approximately 30% of the risk for gallstone formation is hereditary, whereas 70% is environmental, with diet being the primary environmental factor. As mentioned previously, prolonged fasting, TPN, ileal resection, vagotomy, hemolytic states, and cirrhosis are additional risk factors, and many of these factors lead to black pigment stone formation. Finally, bile duct stasis, as occurs with biliary strictures, congenital cysts, chronic pancreatitis, sclerosing cholangitis, and perivaterian duodenal diverticula, is the primary risk factor for brown pigment stone formation.

Natural History

An understanding of the natural history of gallstone disease is necessary for the appropriate management of patients with cholelithiasis. The presence or absence of symptoms remains the most important factor in the determination of the natural history of gallstones. Gallstone disease can be considered as a spectrum of clinical entities that includes asymptomatic gallstones, symptomatic gallstones, and complicated gallstone disease. The complications of gallstone disease include (a) acute cholecystitis, (b) choledocholithiasis with or without cholangitis, (c) gallstone pancreatitis, (d) gallstone ileus, and (e) gallbladder carcinoma.

Asymptomatic gallstones often are discovered at the time of laparotomy or during abdominal imaging for nonbiliary disease. The vast majority of patients with gallstones are asymptomatic. These stones remain in the gallbladder and do not obstruct the cystic duct. As a result, the gallbladder fills and empties normally, and the gallstones remain silent. However, asymptomatic gallstones can progress to symptomatic disease. Symptomatic gallstones usually present with what is termed biliary colic, right upper quadrant or epigastric abdominal pain that typically develops postprandially and may be associated with nausea and vomiting. The pain results from the impaction of a gallstone at the neck of the gallbladder or cystic duct.

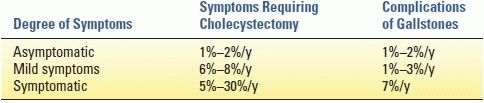

Studies that have followed asymptomatic patients have shown that 20% to 30% of patients become symptomatic within 20 years. Approximately 1% to 2% of asymptomatic individuals with gallstones per year develop serious symptoms or complications related to their gallstones (Table 23.1). The longer stones remain silent, the less likely symptoms are to develop. In addition, almost all patients will develop symptomatic disease before developing one of the complications of gallstones. Therefore, prophylactic cholecystectomy generally is not indicated in patients with asymptomatic gallstones.

TABLE 23.1 Natural History of Gallstones

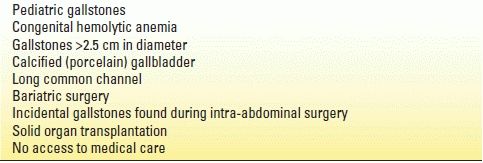

In select groups of patients, however, prophylactic cholecystectomy should be considered (Table 23.2). Children with gallstones almost always develop symptoms and should be considered for early cholecystectomy. In patients with sickle cell disease, cholecystitis can precipitate a crisis with substantial operative risks. Therefore, these patients are best treated with elective cholecystectomy. A nonfunctioning gallbladder usually indicates advanced disease with more than 25% of these patients developing symptoms that require cholecystectomy. Large gallstones (>2.5 cm) are more frequently associated with acute cholecystitis and gallbladder carcinoma, and prophylactic cholecystectomy also may be indicated in these patients. The presence of a porcelain gallbladder (calcified gallbladder wall) is associated with a 5% to 10% risk of malignant transformation, and prophylactic cholecystectomy has been recommended for these patients. A long common channel between the bile and pancreatic ducts also is a significant risk for gallbladder cancer, and these patients should undergo prophylactic cholecystectomy. In obese patients in whom gallstones have already developed and who undergo bariatric surgery, cholecystectomy may be indicated because symptoms are likely to develop and may be difficult to distinguish from those caused by complications of the operation. Prophylactic cholecystectomy adds minimal morbidity and mortality risks to most bariatric operations and is clearly indicated in patients with gallstones. Finally, acute cholecystitis is a potentially life-threatening condition in immunosuppressed patients. For this reason, prophylactic cholecystectomy has been recommended prior to solid organ transplantation.

TABLE 23.2 Indications for Prophylactic Cholecystectomy

Patients with mild symptoms (intermittent biliary colic) are at higher risk for developing gallstone-related complications than asymptomatic patients who have gallstones (Table 23.1). Approximately 1% to 3% of mildly symptomatic patients per year will develop gallstone-related complications, and at least 6% to 8% per year will require a cholecystectomy to manage their gallbladder symptoms. The diagnosis of symptomatic gallstones requires the presence of characteristic symptoms and the documentation of gallstones on diagnostic imaging.

Cholecystitis

Chronic Cholecystitis

The term chronic cholecystitis implies an ongoing or recurrent inflammatory process involving the gallbladder. In more than 90% of patients, gallstones are the causative factor and lead to recurrent episodes of cystic duct obstruction manifest as biliary pain or colic. Over time, these recurrent attacks can result in scarring and a nonfunctioning gallbladder. Histopathologically, chronic cholecystitis is characterized by an increase in subepithelial and subserosal fibrosis and a mononuclear cell infiltrate. The primary symptom associated with chronic cholecystitis or symptomatic cholelithiasis is pain, often labeled biliary colic. The pain is usually located in the right upper quadrant and/or epigastrium and frequently radiates to the right upper back, right scapula, or between the scapulae. Other symptoms such as nausea and vomiting often accompany each episode. The physical examination is usually completely normal in patients with chronic cholecystitis, particularly if they are pain-free. During an episode of biliary colic, mild right upper quadrant tenderness may be present. Laboratory values such as serum bilirubin, transaminases, and alkaline phosphatase usually are normal in patients with uncomplicated gallstones.

Acute Cholecystitis

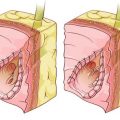

Acute cholecystitis is the most common complication of gallstones occurring in 15% to 20% of patients with symptomatic disease. As in biliary colic, acute cholecystitis results from a stone impaction at the gallbladder–cystic duct junction (Fig. 23.2A). The extent of inflammation and the progression of acute cholecystitis are related to the duration and degree of obstruction. In the most severe cases (5% to 18%), this process can lead to ischemia and necrosis of the gallbladder wall (Fig. 23.2B). More frequently, the gallstone is dislodged, and the inflammation gradually subsides. Acute cholecystitis is primarily an inflammation and not an infectious process with bacterial infection appearing as a secondary event. Approximately 50% of patients with acute cholecystitis will have positive bile cultures, with Escherichia coli being the most common organism.

FIGURE 23.2 A. Acutely inflamed, edematous gallbladder with solitary pigment stone obstructing the cystic duct. B. Gangrenous cholecystitis with solitary black pigment stone.

Patients with acute cholecystitis typically present with right upper quadrant pain that is similar to that of biliary colic. In acute cholecystitis, however, the pain is usually unremitting, may last several days, and is often associated with nausea, emesis, anorexia, and fever. On physical examination, patients with acute cholecystitis usually have a low-grade fever and exhibit localized right upper quadrant tenderness and guarding. The presence of Murphy sign, an inspiratory arrest during deep palpation of the right upper quadrant, is the classic physical finding of acute cholecystitis. A palpable right upper quadrant mass is appreciated in one-third of patients and usually represents omentum that has migrated to the area around the gallbladder in response to the inflammation. Severe jaundice is rare, but mild jaundice may be present in up to 30% of patients. Severe jaundice suggests the presence of CBD stones, cholangitis, or Mirizzi syndrome, obstruction of the common hepatic duct by severe pericholecystic inflammation resulting from impaction of a large stone in the Hartmann pouch. Laboratory evaluation can show a mild leukocytosis (white blood cell [WBC] count 12,000 to 15,000 cells/mm3). However, many patients have a normal WBC. A white cell count greater than 20,000 should suggest further complications of cholecystitis, such as gangrene, perforation, or cholangitis.

Biliary Dyskinesia

A subgroup of patients presenting with typical symptoms of biliary colic (postprandial right upper quadrant pain, fatty food intolerance, and nausea) will not have any evidence of gallstones on ultrasound examination. The vast majority of these patients are women who frequently are overweight or obese. Experimental work suggests that excess fat and cytokines in the gallbladder wall (steatocholecystitis) may be the underlying cause for this phenomenon. Many of these gallbladders are enlarged at rest suggesting that a defect in absorption/secretion may be a contributing factor.

Further investigations usually are performed in these patients to exclude any other pathology. This workup often includes an abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan, an esophagogastroduodenoscopy, or even an endoscopic retrograde cholangiogram. In these patients, the diagnosis of biliary dyskinesia or chronic acalculous cholecystitis should be considered. The cholecystokinin-Tc-HIDA scan has been useful in identifying patients with this disorder. Cholecystokinin (CCK) is infused intravenously, and the gallbladder ejection fraction (EF) is calculated. An EF of less than 35% at 20 minutes is considered abnormal.

DIAGNOSTIC IMAGING

Abdominal X-Rays

In general, plain abdominal x-rays have a low yield in diagnosing biliary tract problems. Plain films are most useful in diagnosing other causes of acute abdominal pain such as a perforated viscus or a bowel obstruction. Only approximately 15% of gallstones contain sufficient calcium to appear radiopaque on a plain x-ray. Rarely, abdominal films may show a calcified gallbladder wall or pneumobilia that may aid in the diagnosis of biliary disease.

Ultrasound

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree