Gallbladder cancer is an aggressive malignancy with a generally poor prognosis. Described for the first time in two autopsy cases by Stoll and his colleagues in 1777, it is the most common malignant tumor of the biliary tract and the sixth most common gastrointestinal cancer.1,2 Complete surgical resection provides the only hope of long-term cure and survival. Despite an increasing number of patients diagnosed incidentally, most patients are found with advanced disease when potentially curative treatment is not feasible and palliative therapy is the only option.3

One of the features of the global pattern incidence of gallbladder cancer is the variation on the basis of geography and ethnicity. Though it is common in the Indian Subcontinent (India, Pakistan), South America (Chile, Bolivia), East Asia (Korea, Japan), and Central Europe (Slovakia, Poland, Czech Republic), it is relatively infrequent in other parts of Europe, North America, and Australia/NewZealand.3 Crude incidence rates for females range from 1.45 per 100,000 in United States to 25.3 per 100,000 in Chile.4 However, regional variations in the same country are also notable—in Argentina a markedly higher incidence is found in the North (Province of Salta) with 6.7 per 100,000 population than in other provinces.5 Certain ethnic groups such as Hispanics, American Indian Natives, Mexican Indian Natives, and Chilean Mapuche Indians are identified as high-risk groups for gallbladder cancer.4 There are multiple potential heterogeneous factors of both genetic and environmental origins. For instance, Hispanic Americans without direct lineage from indigenous New World ancestors do not appear to be at high risk for gallbladder cancer.6 Gallbladder cancer is the leading cause of cancer death among women in Chile and the highest mortality rates were reported in the Araucanía region (35 per 100,000 population).7

The incidence is three times higher among women than men, making gallbladder cancer one of the few non-reproductive-organ-related cancers having a female predominant distribution. Recent findings raise the possibility that gallbladder carcinogenesis may have estrogen- or progesterone-mediated features.3 The mean age at diagnosis falls in the sixth or seventh decade, with exceedingly rare presentations in persons younger than 30 years.8 The strongest risk factors for gallbladder cancer include cholelithiasis, obesity, anomalous pancreatobiliary junction, mucosal microcalcifications, and gallbladder polyps.9 The most relevant associated feature is comorbid gallstones present in 60% to 80%.3 The relative risk of developing carcinoma of the gallbladder has been estimated at between 2 and 24 times higher than in patients without cholelithiasis depending on the study population involved.1 The strong association between gallstone formation and neoplasia appears to be the principal determinant of risk factors such as female gender, increased age, fecundity, and obesity. Other risk factors, related to chronic inflammatory processes, such as porcelain gallbladder, chronic cholecystitis, or pancreatobiliary maljunction share etiologic mechanisms similar to gallstone disease. Reported incidence of cancer in patients with a porcelain gallbladder range from 10% to 20%.10 However, it seems that the pattern of calcification is the most relevant characteristic with focal mucosal calcifications posing the greatest risk over the diffuse transmural calcifications.6 Chronic inflammation is developed also in patients with an anomalous junction of the pancreatobiliary duct, produced by the reflux of pancreatic secretions into the biliary tree. Several studies reported the relationship of gallbladder polyp size and the risk of developing a gallbladder cancer.1,4 An increased risk has been associated with polyps greater than 10 mm, solitary and symptomatic.3 The relationship between bacterial infection and oncogenesis has been already characterized for different types of cancers. Biliary bacteria modify the degradation of bile salts with the formation of carcinogen agents. Salmonella typhi and Helicobacter had been advocated to play a role in the chronic inflammation and mutagenesis in this disease.3,9 Also cigarette smoking, and environmental and dietary cofactors have been associated with gallbladder cancer.1

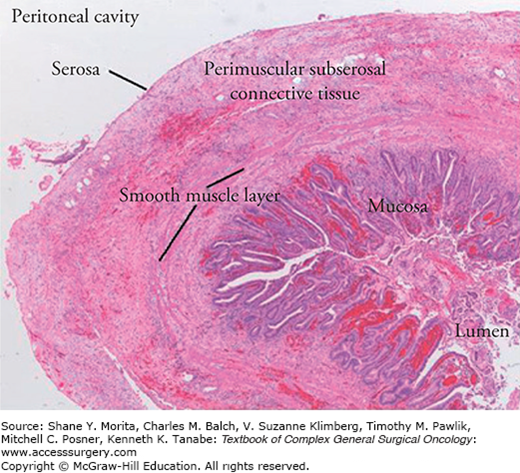

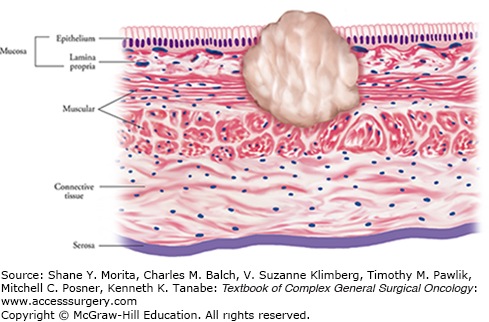

Gallbladder presents a thin wall (<3 mm) composed histologically of four layers: (1) a columnar epithelium and lamina propria, (2) a smooth muscle layer, (3) a perimuscular connective tissue layer, and (4) a serosa (Fig. 135-1). Some anatomical features of this organ are relevant for tumor invasion. The thin muscularis propria is discontinuous and without distinct layer such as the muscularis mucosa or submucosa, and the serosa is absent in the area where the gallbladder is in direct contact with the liver. Hence, invasion of the gallbladder cancer through the first muscle layer places the cancer outside the organ, and along the parenchymal side it leads to direct invasion of the liver. Located in the inferior side of the liver (gallbladder fossa) at the junction of segments 4B and 5, the gallbladder lies in proximity to major portal structures (bile duct, portal vein), duodenum, and colon. A thorough comprehension of the patterns of dissemination is essential in the management of this entity. The disease spreads through the lymphatic, hematogenous, and endoluminal routes and by direct invasion.11 Understanding the anatomy of the lymphatic drainage is crucial for an accurate staging and therapeutic decision. The lymphatic drainage follows four routes to the hilar, the retropancreatic, the celiac, and the mesenteric group of lymph nodes.3

Patients with gallbladder cancer may present with different scenarios. The symptoms are usually associated with the type of clinical presentation. The two most typically defined clinical presentations are discussed below.

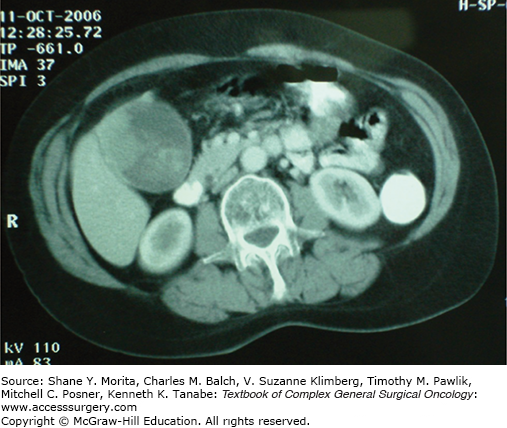

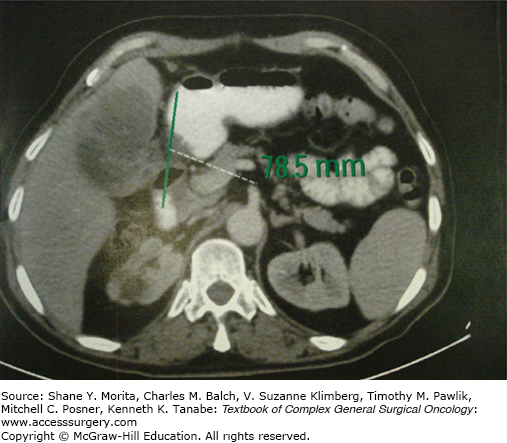

Suspected gallbladder cancer, also defined as “nonincidental,” is a gallbladder mass identified preoperatively by imaging studies. It can range from a local or diffuse wall thickening (Fig. 135-2) to a polypoidal tumor (Fig. 135-3) or a gallbladder fossa mass with entrapped stones and invasion of adjacent structures (Fig. 135-4). Nonspecific symptoms such as nausea, abdominal pain, or weight loss may mimic those of a benign gallbladder disease. Jaundice is the result of direct invasion of the common bile duct, and ductal compression by the tumor or by the involved lymph nodes. Patients with a suspicion of cancer prior to surgery are more likely to be found inoperable at the time of diagnosis.12 There is consensus that with a suspicion of gallbladder cancer, laparoscopic cholecystectomy should be avoided as it may be associated with bile spillage in 20% to 44% of the patients.13,14 Attempts at laparoscopic dissection and partial cholecystectomy in this setting are associated with an increased risk of bile spillage, peritoneal dissemination, and recurrence.15

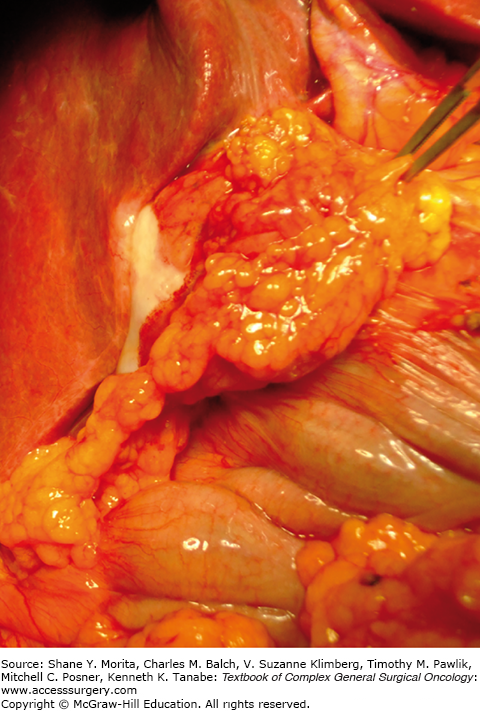

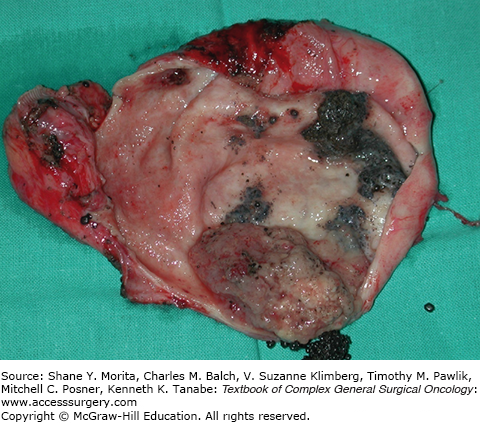

Incidental gallbladder cancer in most cases is discovered on the histopathological examination following cholecystectomy. Since the advent of laparoscopic cholecystectomy the incidence of this clinical presentation has increased significantly and it now constitutes the most common presentation of the disease.13,16 Patients are generally asymptomatic and usually referred to major hepatobiliary centers following the diagnosis.4,14 In this situation special emphasis should be given to obtain the operative protocol of the previous cholecystectomy. Certain information such as bile spillage or biopsy attempts could be useful considering its association with an increased risk of recurrence.13 Alternatively, gallbladder cancer can occasionally be detected intraoperatively, at the time of cholecystectomy, either in the initial operative inspection or when the gallbladder is open after the operation (Figs. 135-5 and 135-6). By far it is the less common presentation, and the recommendation is that if a radical resection is required the procedure should usually be deferred to evaluate and consent appropriately the patient. Similar survival was demonstrated in patients treated by immediate versus deferred resections.13,14 Also the consideration to proceed with a radical oncologic operation will depend on the surgeon-team skills and center resources. In several countries, such as Argentina, this is a relevant issue considering most of the patients with incidental gallbladder cancers are referred to an hepato-pancreatico-biliary HPB center for the definitive reoperation.16

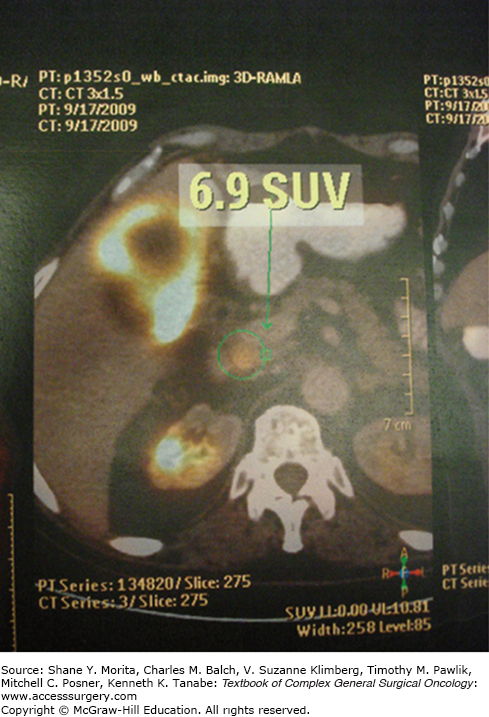

The three common radiological patterns of gallbladder cancer are the mass or exophytic type (40% to 65%), infiltrating type (20% to 30%), and polypoid type (15% to 25%). The exophytic type may appear on ultrasound as a mass of variable echogenicity filling the entire lumen of the gallbladder. A focal or diffuse irregular thickening of the gallbladder wall constitutes the infiltrating type. The polypoid type presents as an heterogeneous intraluminal fungate mass with a nodular or smooth contour (Fig. 135-3).3 Ultrasound evaluation has been the cornerstone for detecting gallbladder pathologies. It is particularly useful in detecting the presence of an obvious gallbladder mass or gallbladder wall thickening. Gallstones may disturb the visualization of tumors. It is important to focus on the gallbladder wall, ignoring distractions from the luminal stones. Any gallbladder wall thickness over 3 mm, focally or diffusely with enhanced vascularity, should alert the physician, especially in endemic areas for gallbladder cancer. Ultrasound can also reveal the presence of porcelain gallbladder, invasion of adjacent structures, vascular invasion, biliary invasion, lymphadenopathies, and ascites. For differential diagnosis, tumorous sludge, other causes of wall thickening (e.g., cholecystitis), benign polyps, and other malignancies should be noticed. The sensitivity of ultrasound to recognize gallbladder cancer is around 40% but increases in advanced tumors.6 Multidetector computed tomography (MDCT) provides 84% accuracy in the detection of gallbladder cancer.6 It is an important tool to assess early lesions, extension into adjacent structures (especially portal vein and hepatic artery), and to accurately stage the disease. The mass type may have variable enhancement, an ill-defined contour, and low attenuation areas of necrosis or calcification. The wall thickening also may enhance but there are differences between carcinoma and chronic cholecystitis. CT scan is poor in detecting small metastases in the liver surface and peritoneum.3 Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has been found to be very useful in detecting biliary, vascular, and hepatic invasion. In combination with MR cholangiography and MR angiography, MRI may provide accurate information regarding resectability as a single investigation. Reported sensitivity and specificity for vascular invasion can approach 100% and 87%, respectively.17 Positron emission tomography (PET) demonstrated some benefits in differentiating malignant from benign disease, in the preoperative staging, and in the detection of residual and recurrent disease. The prime advantage demonstrated by PET-computed tomography (PET-CT) over MDCT was its ability to detect unknown metastatic disease in the rest of the body (lymph nodal involvement, distant metastases) as opposed to MDCT which is principally useful in the locoregional staging of the disease (Fig. 135-7). Detection of unknown metastatic disease up to 42% and changes in the management up to 17% had been described with PET-CT.18 In incidental tumors, PET-CT showed its value as a tool for the selection of patients for a potentially curative reoperation.19,20 In one of the largest published series about the use of PET for suspicious gallbladder lesions, the value of this diagnostic method was demonstrated; reported mean standardized uptake value in malignancy was 6.14 versus 3.42 in benign lesions.18 Other study showed a high sensitivity (97.6%) and specificity (90%) in detecting recurrence after resection of gallbladder cancer.21 Recently Leung et al22 showed that the addition of PET to standard staging CT was helpful in 17% of patients to improve classification of equivocal lesions by CT or MRI and identify distant metastatic disease. In the same study the authors conclude that PET may cause harm in 3% of patients with false-positive PET scans that required unnecessary additional procedures.22

Endoscopic ultrasound can be used as a preoperative staging modality to diagnose early gallbladder cancer and also to provide direct access to the gallbladder and lymph nodal tissue through fine-needle aspiration.3,6

Pathologic staging plays a critical role in the management of gallbladder cancer. Most are adenocarcinomas and they can exhibit two different patterns of growth: infiltrating or exophytic. The infiltrating pattern is the most common. The American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) TNM staging for gallbladder cancer has established the standard classification which is most commonly used worldwide (Table 135-1).23 It is based on the level of invasion of the cancer into the gallbladder wall, the involvement of the lymph nodes, and the presence of distant metastases (Table 135-1). For an adequate staging, the pathologist must perform a detailed examination of the extirpated gallbladder to define not only the histologic characteristics of the tumor but also the localization and penetration into the gallbladder wall (Fig. 135-8). Certain aspects increase the difficulty for an appropriate pathological analysis and can be the explanation for discrepancies found in the literature.24 In a laparoscopic cholecystectomy the gallbladder can be severely traumatized making difficult the histologic interpretation. Also proper pathologic evaluation can be often hampered by the inadequate processing of the tissue.24 Other challenging issues are the differentiation between distinct types of early gallbladder cancers (Tis vs. T1a vs. T1b), the difficulties found in tumors with involvement of the Rokitansky Aschoff sinuses, the appropriate documentation of tumors with subserosal versus subhepatic adventitia extension, and the evaluation of the cystic duct margin often not properly sampled.11 The AJCC TNM staging classification is handicapped by the fact that before operation there is no information on the T and N stage to aid in the treatment decision.23 In patients who have already undergone cholecystectomy and the diagnosis of gallbladder cancer is made by the pathology review, only the degree of penetration (T) of the cancer can be assessed. Commonly the cystic node has not been excised and the involvement of other lymph nodes (N) or neighboring structures is not known. In this setting, the decision to do a reoperation for a radical resection is based on the level of invasion of the gallbladder wall, informed in the pathology report and also in the workup that evaluates the extension of the disease. There are other popular staging systems, like the Union for International Cancer Control and the Japanese Society of Biliary Surgery staging systems.25 The differences found in prognosis and survival can be influenced by the staging system used in each regional centers.25

American Joint Committee on Cancer Staging for Gallbladder Cancer, Seventh Editiona,23

| Primary Tumor (T) | DEFINITION |

|---|---|

| Tis | Carcinoma in situ |

| T1a | Tumor invades mucosa (lamina propria) |

| T1b | Tumor invades muscle layer |

| T2 | Tumor invades perimuscular connective tissue; no extension beyond serosa or into the liver |

| T3 | Tumor perforates serosa (visceral peritoneum) and/or directly invades the liver and/or one adjacent organ/structure (e.g., stomach, duodenum, colon, pancreas, omentum, or extrahepatic bile ducts) |

| T4 | Tumor invades main portal vein or hepatic artery or invades two or more extrahepatic organs/structures |

| Regional lymph nodes (N) | |

| N0 | No regional lymph node metastasis |

| N1 | Metastasis to nodes along cystic duct, common bile duct, hepatic artery, and/or portal vein |

| N2 | Metastasis to periaortic, pericaval, superior mesenteric artery, and/or celiac artery lymph nodes |

| Distant metastases (M) | |

| M0 | No distant metastases |

| M1 | Distant metastases |

Several regional differences have been demonstrated in patients with gallbladder cancer. Many studies have compared various aspects of the disease between different regions of the world, showing some variability in ethnic, racial, and gender distribution.2 The rate of gallbladder cancer among women is almost twice that for men in South and North American populations but not in Japan.16,26 Additionally, patients treated in South and North America are significantly younger than Japanese patients, and those treated in Japan has less incidental tumors.26 Gallstones, the most relevant risk factor for gallbladder cancer, are less common in Japan. Only 52% of the gallstone-associated gallbladder cancers were reported in Japanese patients, while 100% have been observed in South American patients.26 Molecular biological studies support the existence of different pathways of carcinogenesis as well as the potential for regional pathogenic differences. Variation in the quality of imaging techniques or interpretation and/or level of suspicion for a cancer diagnosis are potential contributing factors for the differences in the proportion of patients with incidental tumors found in each region.

Surgical resection remains the only potentially curative treatment for gallbladder cancer. The approach of a patient with gallbladder cancer depends on the stage of the disease, the availability of local expertise, the patient’s performance status, and whether the preoperative diagnosis was suspected or not. Incidental tumors necessitate a decision regarding whether a repeat operation will be oncologically necessary and appropriate. In patients in whom gallbladder cancer is diagnosed preoperatively, extent of resection is dependent upon the depth of tumor invasion and the stage of the disease. Despite a significant survival advantage with radical surgery, there is an underutilization of the procedure in the United States and other countries. Overall, only 11.3% of potentially operable patients underwent radical resection in an analysis of 4631 patients with early-stage gallbladder cancer in the United States.27 Another study based on 2955 patients with gallbladder cancer from the SEER (Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results) database reported a low application of the recommended reoperation for incidental tumors: liver resection in only 13% and lymphadenectomy in 7%.8

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree