PEARLS

❖ A sample tool for assessing cognitive changes in the mental status of older adults is the Mini-Mental State Examination.

❖ The Geriatric Depression Scale is a useful tool for assessing depression in older adults.

❖ The Holmes and Rahe Social Readjustment Rating Scale is one of the best known tools for assessing stress levels.

❖ Functional assessment is a method of measuring an individual’s performance.

❖ Numerous functional assessment tools are available for evaluating older persons. Choose the tool best suited to the setting, clientele, mode of administration, and domain to be evaluated.

❖ Standard physical therapy measures, such as strength, range of motion, posture, and gait, change with age and may be better assessed with specific tools and norms designed for older adults.

❖ Cardiopulmonary parameters, as well as nerve conduction velocity, change with age and require different normative values for assessment comparison.

❖ Assessing ethnicity of older adults will help health professionals recognize bias and differences that may obstruct care.

Note: There are numerous assessment tools available for standardized testing and objectifying clinical findings. This chapter certainly is not an exhaustive list of all of the available tools. That being said, many tools are also provided in other chapters and are not included in this chapter. For instance, cardiovascular assessments are provided in Chapter 13, disease-specific tools are provided in Chapter 12, and functional and balance assessment tools and a home safety assessment/checklist are provided in Chapter 9. The authors have made every attempt to comprehensively include clinically substantiated and validated tools as examples of objective measures.

The demands in health care for cost-effective care are pushing rehabilitation and medical professionals to prove the efficacy and efficiency of the care provided. The obvious place for caregivers to begin this process is in the area of assessment. The evolution of medicine and rehabilitation has been a mixture of science, philosophy, sociology, and intuition. Some of the finest practitioners may be some of the worst scientists. However, they may have an extraordinary intuitive sense. Because of this fine mixture, it is difficult to quantify assessments, treatments, and outcomes. Nevertheless, this needs to be done. The work in health care assessment has grown exponentially in the past 30 years, and more tools are being developed and more scrutiny is being applied to treatment interventions and outcomes.

This chapter discusses 3 important components of the physical therapist’s assessment of older adults. The first section discusses mental status measures for older persons, the second the most common functional assessment tools for older adults, and the third the modifications needed when assessing the older person using accepted physical measures, such as goniometry, manual muscle tests, and nerve conduction velocity. Assessments specific to the orthopedic, cardiopulmonary, neuromuscular (including balance measures), and integumentary systems are discussed in Chapters 11, 12, 13, and 14, respectively. Each section provides a detailed example tool.

MENTAL STATUS MEASURES

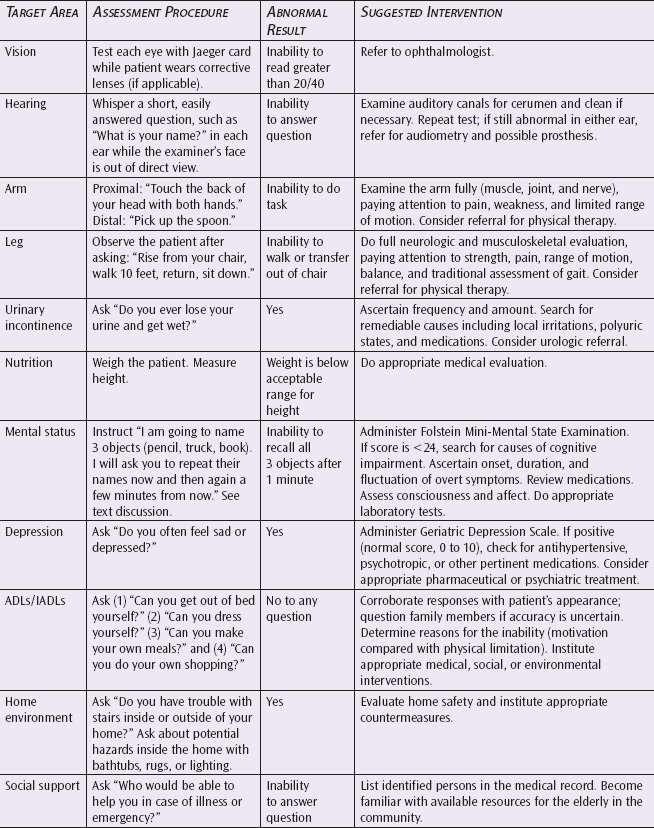

Mini-Mental State Examination

The Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) was published in 1975 by Folstein,1 and it has been widely used since then to assess cognitive changes in older patients. The MMSE was developed to assess patients who have deficits in memory, language, or both. These deficits correlate to intellectual impairment that may indicate Alzheimer disease. The test indicates impairment, but it does not make a diagnosis.2 The MMSE correlates with Wechsler Intelligence Scales and the Wechsler Memory Test, as well as cerebral lesions detected by a computed axial tomographic scan.1,2

The test is relatively easy to administer and takes between 5 and 10 minutes. The test and its instructions for administration can be found in Figure 10-1.

The maximum score possible on this test is 30. A score below 24 indicates cognitive impairment and is not considered normal for older persons. A score of 21 to 24 is considered mild intellectual impairment, a score of 16 to 20 reflects moderate impairment, and a score below 15 is considered severely impaired.1 The MMSE also relates to depression and is indicative of depression at a score of 19. Patients show improvement on the MMSE scores as the depression is ameliorated.3

Depression Measures

Despite the high prevalence of depression in the older population, the diagnosis of depression may be missed.4 However, when screening instruments are used, the recognition of depression is increased.5

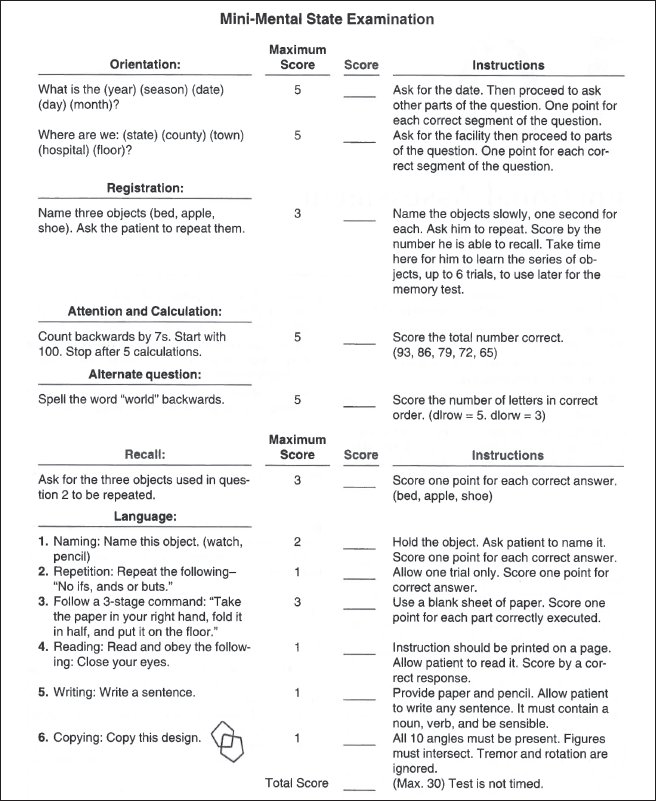

Geriatric Depression Scale

One of the most used tools for depression is the Geriatric Depression Scale. This 30-item, yes or no questionnaire determines that a score of over 8 has a 90% sensitivity and an 80% specificity in detecting depression in the older population.6 There is also a short version consisting of the following 15 questions: 1-4, 7, 9, 10, 12, 14, 15, 17, and 21-23. A score of over 5 on this form may indicate depression.7 The test and the method of scoring are shown in Figure 10-2.

Stress Measures

A final area of psychosocial assessment is stress.

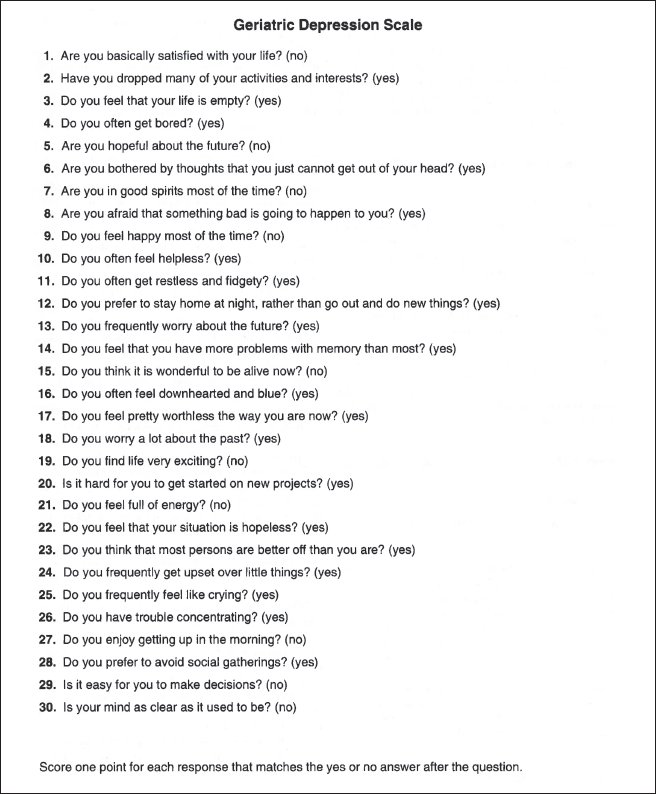

Holmes and Rahe Social Readjustment Rating Scale

The most widely used tool for evaluating stress is the Holmes and Rahe life events scale.8 This scale is shown in Figure 10-3. In administering this tool, the therapist asks the patient to circle the events that have occurred in the past year or will occur in the coming year. The therapist adds up the scores, and the total score is compared to the following scale. A score of below 180 points indicates mild stress or less than a 40% chance of a serious illness in the next year, a score of 180 to 300 indicates moderate stress or a 40% chance of developing a serious illness in the next year, and a score above 300 indicates severe stress or an 80% chance of a serious illness in the next year.8

FUNCTIONAL ASSESSMENT

The word function is repeated 88 times in the current Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services regulations on rehabilitation.9 This fact should encourage rehabilitation professionals to think about and use functional measures because the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services uses these regulations as requirements for payment.

Functional measurement is also important because it differs from the current methods physical and occupational therapists use to assess patient status, and they may not truly reflect a patient’s functional level. These measures, such as range of motion, strength, and other musculoskeletal parameters, may be important to assessment, but they do not always relate to function. If rehabilitation professionals are to show efficacy in what they do, it is important that they assess function in conjunction with musculoskeletal parameters. Combining these 2 assessments will make a truly comprehensive rehabilitation evaluation possible.

A recent study by Mary Tinetti10 scrutinizes the use of musculoskeletal measures. Her study showed very little relationship between musculoskeletal measures and functional outcomes of older patients.10

A third factor contributing to the importance of functional evaluation is the ability to give a beginning and end point based on a functional outcome, as well as a relationship of this outcome to a patient’s independence. For example, the Barthel Index can rate a patient’s difficulty with bathing or walking. The patient’s ability to perform these tasks is assigned a level that is indicated by a number. As the person progresses with treatment, he or she is moved to higher levels. If patients regress, they are ranked at a lower level. In addition, the total scoring on this index indicates to the assessor when the patient is able to go home or is in need of assistance.

These numbers translate to a patient’s specific ability to function and can be very helpful in making decisions related to disposition and the need for continued care. On the other hand, a muscle strength measure indicating normal (5/5) muscle strength means nothing if the person cannot get in and out of a tub or eat independently. The combination of strength and function measures is extremely helpful when assessing cause and outcome.

The purpose of this section is to encourage the health professional to avoid performing unnecessary and time-consuming tests. Many of these functional tests can be done by the patient with paper and pencil prior to the treatment program and on discharge without unnecessarily monopolizing the health professional’s time.

Figure 10-1. Mini-Mental State Examination. (Reprinted with permission from Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. Mini-mental state. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189-198.)

Figure 10-2. Geriatric Depression Scale. (Adapted with permission from Yesavage JA, Brink TL. Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: a preliminary report. J Psych Res. 1983;17:41.)

Figure 10-3. The Holmes and Rahe Social Readjustment Rating Scale. (Reprinted with permission from Holmes T, Rahe R. The Social Readjustment Rating Scale. J Psychosom Res. 1967;11:213-218.)

A final justification of functional evaluation comes from an article written by Robert Kane, dean of the School of Public Health at the University of Minnesota.11 Dr. Kane is a well-respected researcher in gerontology and health care and an advocate for functional assessment for geriatricians. In his article, he states that a specialty is not truly a specialty until it has its own instrument. He gave radiology as an example. This discipline would not have its current credibility or base if it were not for x-rays. Also, cardiology would not have evolved into a specialty if it were not for heart catheterization. He then asserts that geriatrics will truly not be accepted as a specialty until the professionals in that area have a similar tool. He believes that the tool for geriatrics is functional assessment.11

By extrapolating on his thoughts, it can be seen that rehabilitation is an area where functional assessment is a tool, especially for rehabilitation professionals in the area of geriatrics. The following sections follow this argument and advocate functional assessment for rehabilitation professionals, particularly for those working in geriatrics.

What Is Functional Assessment?

Functional assessment differs from traditional assessment in several ways. For example, it targets specific behaviors and tasks a patient wishes to accomplish. If a therapist were to ask a patient, “What do you want from physical therapy?” the patient would not say, “I want my muscles to test normal or 5/5.” Rather, he or she would answer, “I want to increase the strength in my legs” or “I want to run 10 miles pain free.” These responses are rarely indicated in rehabilitation notes or incorporated into work goals. Instead, many notes state that the goal of treatment is to increase strength or function. This is not enough. A goal stated in slightly more specific functional terms is “Increase strength so that the patient is able to run a marathon without pain” or “The patient is able to walk from bed to bathroom unassisted, without falling or losing balance.” An even better functional statement would be a quantified response, such as “The patient scores 80 on the Barthel and can return home independently.”

Richard Bohannon and colleagues,12 in an article in the International Journal of Rehabilitation Research, showed that the number one priority when rehabilitating patients who have sustained a stroke is the patient walking independently. Physical therapists may forget this when implementing various measures and techniques. Therefore, if the focus is on function, therapists will not lose sight of patients’ needs.

The goal of rehabilitation is to assist people in achieving their highest level of function, but confusion often interferes with this. Instead of focusing on the goal, therapists focus on the signs and symptoms. When measuring and treating range of motion, strength, or endurance, the goal of function must be maintained. The second area of confusion and poor implementation of function is the use of function to mean different things (eg, the function of a knee or a hip). Instead, function must be examined in terms of the whole individual13 and, more specifically, how that person functions vs how his or her shoulder functions.

If function is defined as the normal or characteristic performance of the individual,14 the individual is the unit of analysis rather than the body part or organ system. It is not just a shoulder or a kidney that is being studied, it is a whole person. Can the patient reach up into the cabinet even if he or she has a rotator cuff tear, and does he or she need to? Is there some modification that he or she should be taught to adapt to his or her environment?

Understanding function includes more than understanding physical function because there are 4 components of function.15 The first is physical function, which is the component that physical therapists work with the most. This subsection of function includes sensory motor performance, walking, climbing stairs, and other activities of daily living (ADLs). The second component is mental function, including intelligence, cognitive ability, and memory. The third is emotional function, defined as coping with life’s stressors, anxieties, and satisfactions. The fourth is social function. This area looks at a person’s interaction with family members and the community and any economic considerations. A good reference for functional assessment tools in older persons is Kane and Kane’s Assessing the Elderly.13 The next section gives an example of a functional tool.

Functional Assessment Tools

Barthel Index

The Barthel Index is one of the most widely known and well-established physical functional parameters assessment tools.16 It measures toileting, bathing, and ambulation.16 On the Barthel Index, the best score is 100, and the worst is 0. Tasks 1 through 9 have a possible score of 53, and tasks 10 through 15 have a possible score of 47, for a total possible score of 100.

Exploring a few items on this index will demonstrate how it is scored. If a patient can drink from a cup independently, the patient gets 4 points. If, however, the patient needs someone’s help or cannot do it at all, he or she gets 0. The reason this scoring mechanism seems strange is because it is a weighted scale. Weighted scales were developed to correlate with other measures. In a weighted scale, the accomplishment of one item may be more important to a specific measure and is therefore scored higher than others. Because of this weighting, it is imperative to use the numbers shown on the tool.

To administer this test, give a patient the form without the numbers, and allow the patient to check the appropriate column. Later, the scorer can add up the numbers. However, this test is more reliable if a health professional assesses and grades each task as the patient performs it.16

What do the numbers mean? The test reflects the patient’s ability to perform ADLs without an attendant.16 It correlates well with clinical judgment and mortality, as well as with discharge to a less restrictive environment.16 A score of 60 or above means that a person can be discharged home but will require at least 2 hours of assistance in ADLs. If the person scores 80 or above, it means that he or she can be discharged home but will require assistance of up to 2 hours in self-care. When working with a patient who has been assessed as independent in self-care and scores a 50 on the Barthel Index, this would indicate the contrary.

The final question to be answered is when various tools should be used. The most efficient way to use these tools is to have a goal in mind for its use, such as to establish a baseline to show improvement, to screen for problems, to set rehabilitation goals, or to monitor the patient’s progress.17

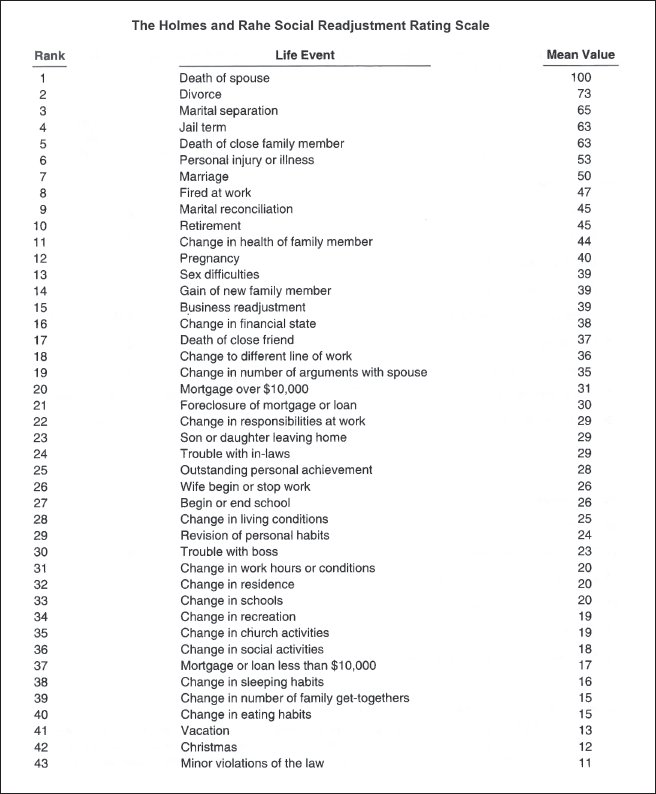

The medical community in general is developing a keen interest in functional assessment. Lachs et al17 and Williams,18 in the Annals of Internal Medicine, urge general practitioners to use functional assessments. In addition, these articles specifically delineate physical therapy as an appropriate referral once functional deficits are noted. Table 10-1 is a procedural chart on functional assessment from Lachs et al’s work.18

Therapists in geriatrics must get involved in functionally assessing patients not only for the efficacious assessment potential but also for continuity of care from medical peers.

MODIFIED PHYSICAL THERAPY MEASURES

Musculoskeletal Parameters

Strength

It is widely accepted that strength decreases with age. However, no studies exist to date that show a difference in the strength decline with age using simple manual muscle test techniques. This makes it difficult for a practitioner to use the current knowledge of age’s strength changes in the clinical setting.

In the realm of dynamometer and muscle hypertrophy, some clinically useful information has been generated. The best sources on muscle hypertrophy are the articles by Tomanek and Woo19 and Goldspink and Howells.20 Basically, these resources contend that older muscle does hypertrophy but not to the same extent. Figure 10-4 contains some formulas for assessing hypertrophy and charts illustrating the comparison in muscle hypertrophy.21

It is apparent from these formulas that the calculation for the difference in muscle hypertrophy is rather cumbersome and not easily applicable in the clinic. The authors suggest being wary of using muscle hypertrophy measures (ie, girth) as the only criteria for assessing muscle strength increases with age.

Dynanometer testing of strength can be replicated in the clinic. Rice22 carried out a simple assessment of numerous joints’ strength using a modified sphygmomanometer. Table 10-2 is his chart of absolute strength measures.22

Borges23 also showed the torque changes with age in the knee using the Cybex dynamometer (Table 10-3).

Finally, Vandervoort and Hayes24 found a 71% decrease in plantar flexor muscle isometric strength in older adults compared with the young. This study was done on both young and old healthy women. Their findings revealed strength development for the young of 0.16 nm/s and 0.09 nm/s in the older group.

In conclusion, the clinical implications of the information noted in the area of strength changes with age are as follows:

❖ Be wary of girth measures as a means of reflecting strength gains.

❖ Compare outcomes to the norms noted. For example, compare knee extension torques to Borges’s measures vs measures of torque on younger persons.

❖ Compare strength measures to Rice’s norms vs the classic manual muscle test for more comparable findings.

Range of Motion

The literature on range of motion norms is still somewhat controversial. For example, Walker et al25 showed no significant differences in range of motion in 28 joints of younger and older individuals (Table 10-4).

Frekany and Leslie26 showed that even if an older group did have motion limitation, it could be normalized with appropriate stretching exercises. James and Parker27 gave probably the most comprehensive and recent reference on joint range of motion norms of the lower extremity (Figure 10-5).

Information also exists on upper extremity and spinal norms for range of motion. These are listed in chart form in Tables 10-5 through 10-8. These findings, even though controversial, can assist the therapist to set more appropriate goals. If, for example, as was stated in Bassey’s chart, the norms for shoulder flexion are 129, then a goal of 170 is inappropriate. Keeping these charts for review can help to design appropriate programs.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree