Introduction

Frailty can be defined as that condition when a person loses the ability to carry out important, practiced social activities of daily living when exposed to either psychological or stressful conditions.1 It should be distinguished from disability. Frailty represents a form of predisability.

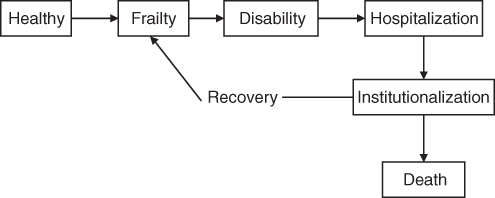

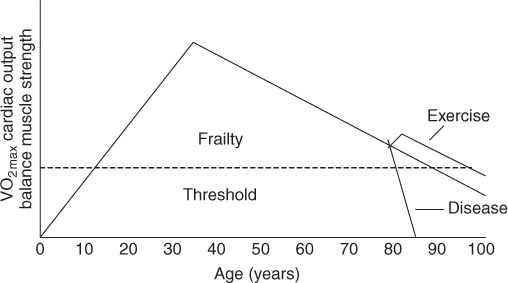

Frailty has been objectively defined by Linda Fried and colleagues (Table 113.1).2, 3 Their definition includes weight loss, exhaustion, weakness, walking speed and low physical activity. By this definition, ∼6.9% of the older population are frail. Females are more often classified as frail than are males of the same age. Two other similar definitions of frailty that are easier to use in the clinic have been validated4, 5 (Table 113.1). Rockwood et al.6 defined frailty as an increasing number of disabilities. Frailty is the beginning of a cascade that leads to functional deterioration, hospitalization, institutionalization and death (Figure 113.1). Over our lifetime, there is a peak in vitality between 20 and 30 years of age, after which there is a gradual physiological decline in performance (Figure 113.2). This decline can be delayed by positive behaviours such as exercise or accelerated by negative factors such as disease. However, eventually all individuals, if they live long enough, will cross the frailty threshold. This chapter discusses the factors involved in the acceleration of the life slope towards the frailty threshold.

Table 113.1 Comparison of three frailty scales.

| Cardiovascular Health Study | Study of Osteoporotic Fractures | International Association of Nutrition and Aging |

|

|

|

Pathophysiology of Frailty

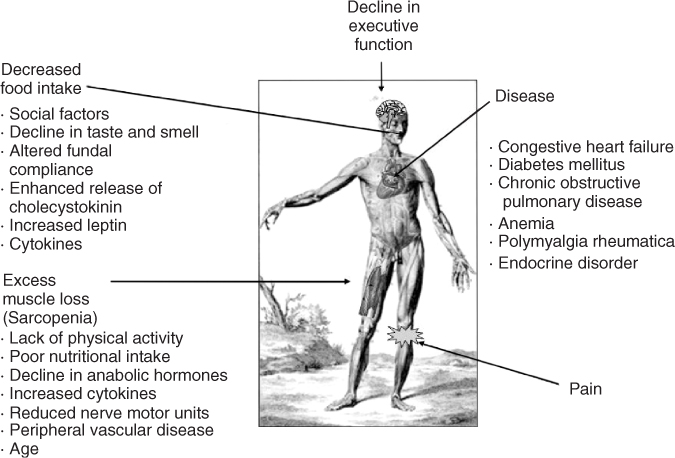

The causes of frailty are multifactorial. The backdrop for the development of frailty is the physiological changes of ageing. The interaction of normal physiology with genes, lifestyle, environment and disease determines which individuals will become frail. In most individuals, frailty is caused by the failure to generate adequate muscle power and/or the failure to have sufficient executive function to utilize the available executive function appropriately. The major causes of frailty are illustrated in Figure 113.3.

Disease

Numerous disease processes can directly or indirectly result in frailty. Many diseases produce an excess of cytokines that can lead to a decrease in muscle mass, food intake and cognitive function. Diseases also lead to a decline in levels of the anabolic hormone testosterone.

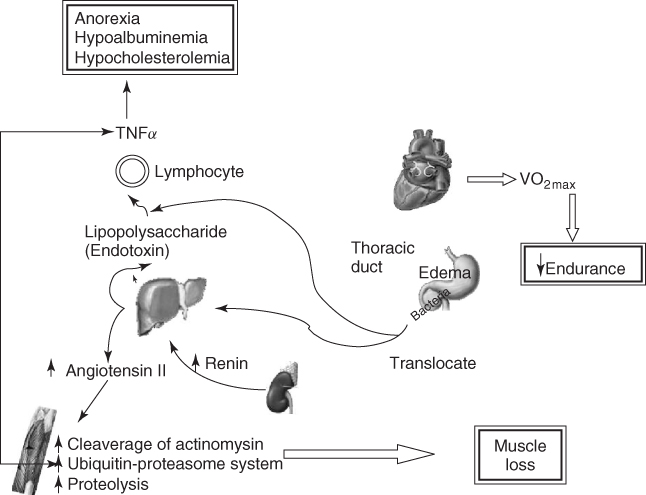

Congestive heart failure (CHF) is a condition that is classically associated with frailty. Persons with CHF have a marked decline in their VO2max, leading to an inability to perform endurance or resistance tasks. Left-sided heart failure leads to intestinal wall oedema. This results in bacterial translocation into the lymphatic and systemic circulation. The bacterial endotoxins (lipopolysaccharides) result in the activation of the immune system and release of cytokines, such as TNF-α. This results in anorexia, loss of muscle mass, weight loss, hypoalbuminaemia and hypocholesterolaemia (Figure 113.4). In CHF, the best predictors of poor outcome are weight loss and hypocholesterolaemia.7 Activation of the angiotensin II system that leads to cleavage of actomyosin and subsequent clearance of muscle protein by the ubiquitin–proteasome system may also play a role. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors reverse weight loss and frailty in some persons with CHF.

Persons with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease have a decrease in endurance, weight loss due to poor food intake and increased resting metabolic rate and thermic energy of eating. They lose muscle because of low testosterone levels and increased circulating cytokine levels.

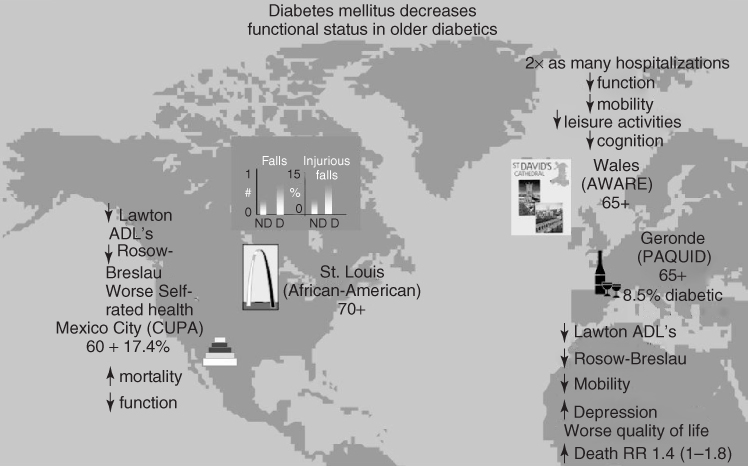

Diabetes mellitus is classically associated with an increase in frailty, injurious falls, disability and premature death (Figure 113.5). Again, the causes are multifactorial and include low testosterone, increased angiotensin II, increased cytokines, peripheral neuropathy, reduced executive function and accelerated atherosclerosis.

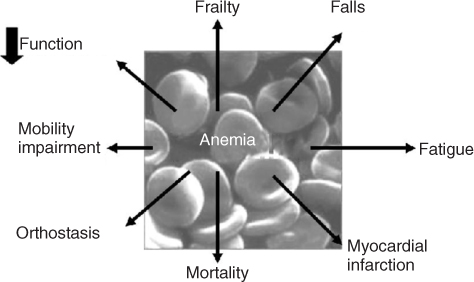

Persons with anaemia have reduced endurance, decreased muscle strength, orthostasis, increased falls, increased frailty, decreased mobility, increased disability and increased mortality (Figure 113.6). Both erythropoietin and darbepoetin-α can reverse the anaemia and many of these changes.8 The use of these agents has led to a marked increase in the quality of life of patients with chronic kidney failure, anaemia of chronic disease and myelofibrosis.

Polymyalgia rheumatica results in painful muscles with proximal myopathy. The diagnosis is confirmed by finding an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate. Treatment of this condition with corticosteroids reverses the frailty that it produces. Unfortunately, this totally reversible condition is often misdiagnosed by clinicians.

Endocrine disorders, such as hyperthyroidism, hypothyroidism and hypoadrenalism, can have insidious onset. Joint pain, that is, the arthritides, is classically associated with immobility. Immobility, over time, leads to loss of muscle mass and power and to a decline in endurance, the hallmarks of frailty. Pain can further induce frailty secondarily to increasing depression in older persons.

Decreased Food Intake

Older persons develop a physiological anorexia of ageing that is associated with a loss of weight. The causes of the anorexia of ageing are multifactorial.9 Social causes, such as isolation and dysphoria, and the decline in smell and increase in taste threshold are obvious causes. Recently, there have been a number of studies that demonstrated that decreased compliance and adaptive relaxation of the stomach result in a more rapid antral filling and early satiety. Excess production of cholecystokinin from the duodenum in response to a fatty meal is another cause of anorexia in older persons. High circulating cytokine levels in older persons have been associated with anorexia. Males have a greater decrease in both absolute and relative amounts of food intake over the lifespan. This appears to be due to the fall in testosterone, which results in an increase in leptin levels and, therefore, greater anorexia.

In addition to the physiological anorexia of ageing, many reversible causes of anorexia occur in older persons. These are easily remembered by the mnemonic MEALS-ON-WHEELS (Table 113.2).

Table 113.2 MEALS-ON-WHEELS mnemonic for treatable causes of weight loss.

| Medications (e.g. digoxin, theophylline, cimetidine) |

| Emotional (e.g. depression) |

| Alcoholism, elder abuse, anorexia tardive |