Introduction

Diseases and disorders of the foot and related anatomical structures affect the QOL (quality of life), dignity and the ability of individuals to remain independent and to live life, to the end of life. Foot problems in the older population result from disease, disability and deformity related to multiple chronic diseases as well as focal changes associated with repetitive use and trauma. Older people are at high risk of developing foot-related disease and should receive continuing assessment, education, surveillance and care. The foot is a mirror of health and disease.1

The human foot is unique. It evolved to serve as an interface between man and whatever territory he or she most commonly traverses, resulting in a wide range of adaptations to use. Those whose footwear is minimal because of climatic conditions or the nature of territory require little or no covering; have feet that are different from those in industrial civilizations and are related to the needs of society and custom. Feet are required to withstand variable repetitive stress imposed by activities and occupations. The forces of pressure, the adaptations required for ambulation, prior care and the effects of disease and ageing, present different problems in the elderly making comprehensive podogeriatric assessment an essential in patient evaluation and increasing the need for the continuing assessment and examination of the feet and related structures, followed by appropriate care, management, surveillance, education and preventive strategies. All health policies should include appropriate and proper podiatric services.2

At one extreme may be the long periods of limited movement that present particular occupational risks. At the other end of the scale may be those occupations, activities and/or interests involving great variability of movement that includes weight/stress-related involvements. All these leave their mark upon the foot in the form of a wide range of morbidities, which usually manifest in later life and produce residual disability in the elderly. Some may produce discomfort or temporary disability. Others will produce insidious but cumulative effects that cause podalgia, ambulatory dysfunction and limitation of activity. As age increases, problems that may have been tolerated in earlier years will limit the mobility of the individual and decrease the QOL. The focus in the management of the older patient may turn from cure to comfort and providing a means to maintain ambulation in order to retain one’s independence and dignity.

The feet are covered with hosiery and then thrust into coverings that hide them from view for long periods of time. Footwear, either hosiery or shoes, does not always complement the size and/or shape or function of the foot. Extremes in width, length, last, or depth of the foot will complicate shoe fitting, even with a relatively wide range of mass-produced footwear. This potential functional incompatibility between anatomy and coverings potentiates problems, which become more evident and pronounced in later life. Congenital and/or acquired and disease processes may deform feet in a variety of ways which will result in difficulties throughout life and require proper care over long periods of time to manage these chronic diseases and impairments, such as changes in the circulatory and neurological systems. The primary treatment goals include the relief of pain, restoring the individual to a level of maximum function, and maintaining that function once achieved. Fashion in footwear cannot be disregarded. When style predominates over fit and function, foot problems are again initiated and/or exacerbated due to this functional incompatibility that is many times, with a foot to shoe last (model, design, or shape) incompatibility.3–5

Risk Disorders with Pedal Manifestations

Foot problems and their management are not always regarded as an essential part of some general health programmes or even as being related to general health. The exception is usually related to the catastrophic effects of diabetes mellitus, such as amputation. It is significant but regrettable, that many believe that feet are a part of the body that is designed to hurt. This is true for patients and other elements of the healthcare systems. A majority of patients expect to be able to pursue their normal activities and occupations despite the presence of foot conditions that require rest, but not necessarily hospitalization. With advancing age and the changes in older adult lifestyle, including assisted living and long-term care, these concerns magnify and may be the difference between living life with some quality and sedentary institutionalization. In addition, because of age-related changes and disease, patients are frequently unable to reach their feet because of arthritis, failing eyesight, obesity, postural hypotension, or some other related disorder. Continuing assessment, evaluation and appropriate care is most essential for the ‘at-risk’ older patients. Tables 92.1 and 92.2 identify some of the primary risks associated with the development of foot problems in the older population (for an example, see also Figure 92.1).

Table 92.1 Generalized risk.

|

Table 92.2 Other related risks.

|

The primary risk diseases that present with significant pedal manifestations as identified by Medicare are summarized in, but not limited to, Table 92.3 as follows:

Table 92.3 Primary risk diseases.

|

Note: Those conditions marked with an asterisk (*), require medical evaluation and care within 6 months of their primary foot care service.

On 16 June 2009, the Department of Veterans Affairs (VHA Directive 2009-030) expanded the Medicare primary risk categories to appropriately include those conditions listed in Table 92.3A

Table 92.3A Primary risk categories.

|

A secondary list of systemic ‘at-risk’ conditions are summarized but not limited to Table 92.4. There are also specialized risks identified in, but not limited to Table 92.5.

Table 92.4 Secondary risk conditions.

|

Table 92.5 Specialized risks.

|

Joint diseases such as arthroses, gout, rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis are frequently manifested in the feet. Their primary clinical findings are noted but not limited to those listed in Table 92.6 (gout), Table 92.7 (rheumatoid arthritis), and Table 92.8 (osteoarthritis or degenerative joint diseases).

Table 92.6 Gout.

Acute

|

Chronic tophaceous gout

|

Table 92.7 Rheumatoid arthritis.

|

Table 92.8 Degenerative joint diseases: osteoarthritis.

|

In the older patient, the consequences of these diseases usually result in deformity, swollen joints, impaired foot function, and an altered and potentially podalgic gait. In many cases, the foot may be the primary site of deformity, disability and limitation of activity that makes weight bearing difficult and causes significant problems in obtaining adequate footwear to compensate for the residuals of these diseases.

Variable and wide-ranging effects accompany endocrinopathies, such as diabetes mellitus, in the cardiovascular and neurological systems. Many of the symptoms and

complications associated with the disease are manifested in the feet and produce potential and serious complications in the older patient. The changes involving the foot are the cause for a significant number of potentially life-threatening hospitalizations. In addition, it has been estimated in the United Kingdom and United States, that 50–75% of all amputations relating to the complications associated with diabetes mellitus could be prevented and reduced with an appropriate programme of preventive foot care and foot health education.

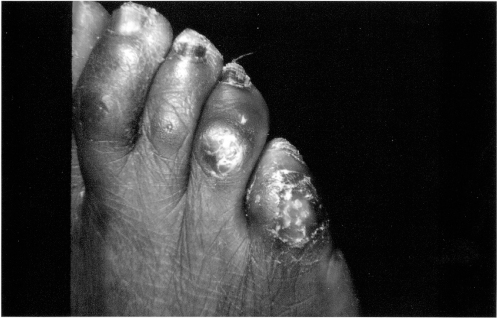

The most common clinical findings relating to the diabetic foot are listed but not limited to those in and Table 92.9 (for an example, see also Figure 92.2).

Table 92.9 Diabetic foot changes.

|

To these problems one must add the effects of repeated microtrauma from footwear, environmental surfaces, lifestyle, neglect and heat-reflecting surfaces, which produce hyperkeratosis and subkeratotic haemorrhage, a predisposing factor for ulceration. Diabetic foot problems in the elderly are characterized by paresthesias, numbness, sensory impairment, a loss of pain sensation, motor weakness, reflex loss, neurotrophic arthropathy, absence of pedal pulses, atrophy, infection, dermopathy, angiopathy, peripheral neuropathy, ulceration and necrosis/gangrene.6

Clinically, the most marked change perhaps for the elderly diabetic is sensory neuropathy. When combined with visual impairment, the elderly can be completely unaware of their feet. Paralysis of intrinsic foot muscles due to motor neuropathy will result in deformities of the toes, claw toes. The bony prominences thus formed on the dorsum of the toes and the plantar aspect of the metatarsophalangeal joints may be the site of skin lesions, such as hyperkeratosis (tyloma and/or heloma, i.e. corns and calluses), and/or the sites of ulceration, due to pressure, residual subkeratotic haemorrhage and local tissue ischaemia.

The plantar surface of the foot has been the most common site for the development of diabetic ulceration, which is trophic in character. These ulcers develop underneath keratosis with pressure and thus the skilled and proper débridement of the keratosis is a prerequisite to the successful management of the diabetic ulcer and in the prevention of ulcer development (see Figure 92.3). Appropriate weight diffusion and dispersion procedures are also essential elements to management, particularly in the elderly.

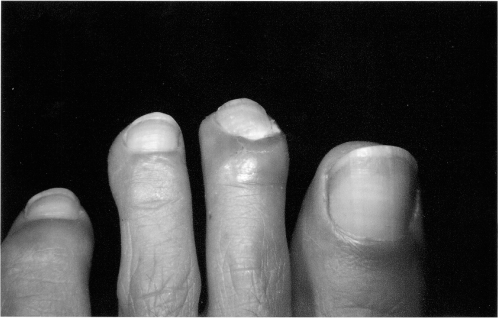

Figure 92.3 Multiple hammer toes, heloma, preulcerative keratosis, subungual haematoma, peripheral arterial disease, trophic changes.

Skin texture and sweating patterns are also markedly altered in the elderly diabetic, due to autonomic neuropathy and oedema. The consequent enlargement of the foot is another cause of epidermal abrasions of the skin from footwear and other forms of trauma and pressure. The management of infection becomes complicated unless appropriate metabolic management is instituted and maintained early in the disease process. The resulting sepsis can lead to necrosis, gangrene and amputation of the limb, which additionally complicates the management of the disease in the elderly as well as necessitating changes in the patient’s lifestyle.7

Varicose veins are a common manifestation in the legs and feet of the elderly. Varices may be observed on the dorsum of the foot sometimes extending as far as the toes, and also along the medial plantar arch area. Haemosiderin deposited in the skin over the lower one-third of the leg and the foot, giving them a freckled appearance and sometimes imparting a coppery hue where the change becomes marked. Oedema of the foot and ankle also are a frequent accompaniment of varicose veins. Trauma to these vessels can produce haemorrhage. The diminished blood flow resulting from the presence of varicose veins impairs wound healing and causes trophic changes in the skin and nails. Adhesive dressings, even though they may be hypoallergenic, are not well tolerated by such skin for prolonged periods of time. Appropriate treatment may be required to improve both the appearance and function of the extremity.

Complicating factors of venous disease in the elderly include thrombophlebitis, deep venous thrombosis, and postphlebitic syndrome, which produce an ‘at-risk’ status for the patient with foot problems.

The more common arterial diseases that can be observed in the elderly include the residuals of vasospastic disease, such as Raynaud’s disease or phenomenon, acrocyanosis, livedo reticulosis, pernio and erythromelalgia. Occlusive diseases such as arteriosclerosis obliterans, the residuals of thromboangiitis obliterans and related diseases, such as arteritis, periarteritis nodosa, polymyalgia rheumatica, systemic lupus erythematous, erythema nodosum, erythema induratum, nodular vasculitis and hypertensive arteriolar disease. The primary risk factors for the development of peripheral arterial diseases in older patients include smoking, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, Buerger’s and Raynaud’s diseases. With inadequate perfusion, non-healing wounds, infection, tissue loss and amputation are complications. The primary clinical findings associated with arterial insufficiency are summarized but not limited to those listed in Table 92.10.

Table 92.10 Primary clinical vascular findings.

| Fatigue |

| Rest pain |

| Coldness |

| Decreased skin temperature |

| Burning |

| Colour changes |

| Absent or diminished digital hair |

| Tingling |

| Numbness |

| Ulceration |

| History of phlebitis |

| Cramps |

| Oedema |

| Claudication |

| History of repeated foot infections |

| Diminished or absent pedal pulses |

| Popliteal and/or femoral pulse change |

| Colour changes—rubor—erythema and/or cyanosis |

| Temperature changes—cool—gradient |

| Xerosis, atrophic and dry skin |

| Atrophy of soft tissue |

| Superficial infections |

| Onychial changes |

| Onychopathy |

| Onychodystrophy |

| Nutritional changes |

| Subungual haemorrhage |

| Discolouration |

| Onycholysis |

| Onychauxis (thickening) |

| Onychorrhexis (longitudinal striations) |

| Subungual keratosis |

| Deformity |

| Blebs |

| Varicosities |

| Delayed venous filling time |

| Prolonged capillary filling time |

| Femoral bruits |

| Ischaemia |

| Necrosis and gangrene |

In the geriatric patient, arterial insufficiency is heralded by rest pain or nocturnal cramps and/or intermittent claudication. Although it is usually brought on by exercise or use, it may also occur at rest in severe cases of arterial occlusion. Any muscle may claudicate and thus foot pain in the elderly may be related to arterial insufficiency rather than biomechanics or pathomechanics. Painful ulcerations may occur over bony prominences and result from minor trauma and/or pressure. Smoking must be prohibited. Appropriate vascular studies, such as: imaging (arteriography, digital subtraction angiography, MRI, CT arteriography and Doppler imaging), non-invasive studies (Doppler, oscillometric, ankle-brachial index, segmental pressure measurement, plethysmographic waveform analysis, pulse volume recording, skin perfusion pressure, laser Doppler pressure, colour Doppler, ultrasonography, transcutaneous oxygen content (TcPO3), cutaneous oximetry and treadmill exercise testing), and surgical consideration should be provided when pain is uncontrolled and/or when ulceration and infection are significant.

Because of the risk involved in the geriatric patient and the relationship to multiple chronic diseases, assessment, examination and evaluation of the feet and related structures, are essential. Elements of this process include needs, relationships to ambulation and activities of daily living (ADL), instrumental activities of daily living (IADL), and the fact that foot pain can result in functional disability, dysfunction and increased dependency.

A Comprehensive Podogeriatric Assessment Protocol (Helfand Index), has been developed by the Pennsylvania Department of Health in cooperation with Temple University, School of Podiatric Medicine and is included as Table 92.11.

Table 92.11 Podogeriatric assessment protocol developed under a contract to the Pennsylvania Department of Health as the ‘Helfand Index’ by Arthur E. Helfand, DPM. Reproduced with permission.

| Date of visit MR# |

| Patient’s name Age |

| Date of birth Social Security# |

| Address |

| City State Zip code |

| Phone number |

| Sex M F Race B W A L NA |

| Weight in Pounds Height in Inches |

| Social status M S W D SEP |

| Name of primary physician/health-care facility |

| Date of last visit |

History of Present Illness Swelling of feet Location Painful feet Quality Hyperkeratosis Severity Onychial Changes Duration Bunions Context Painful toe nails Modifying factors Infections Associated signs and symptoms Cold feet Other |

Past History Heart disease Diabetes mellitus High blood pressure * IDDM Arthritis * NIDDM * Circulatory disease Hypercholesterol Thyroid Gout Allergy History of Smoking—Alcohol—Substance Abuse Family—Social |

Systems Review Constitutional ENT Card/Vasc GU Eyes Musculo-Skeletal Neurologic Skin—Hair—Nails Skeletal Endocrine Respiratory GYN GI Psychiatric Allergic Immunologic Hematologic Lymphatic |

| Medications |

Dermatologic * Hyperkeratosis Xerosis Onychauxis B-2-b Tinea pedis Infection Verruca * Ulceration Hematoma Onychomycosis Rubor Onychodystrophy * Preulcerative * Cyanosis B-2-e Discolored |