68.1

Epidemiology of falls and fall-related injuries in older people

A fall is “an event which results in a person coming to rest inadvertently on the ground or floor or other lower level” . Falls represent a major age-related health challenge facing our society, with about one-third of community-living older people falling at least once a year. Approximately one-quarter of falls result in physical injury incurring high costs in terms of decreased quality of life as well as significant health and social care expenditure. Falls can mark the beginning of a decline in function and independence and are the leading cause of injury-related hospitalization in older people.

Prospective studies undertaken in community settings have reported fall incidence rates of 32%–40% , and fall rates increase to 40%–50% in people beyond the age of 75 years . The incidence of multiple falls in 1 year ranges between 11% and 21%. Prospective studies in residential aged care facilities (RACF) report fall incidence rates ranging from 30% to 56% . Falls also occur frequently when people are in hospital, with incidence rates ranging between 2% in general hospitals and 27% in acute hospital geriatric wards .

Fall-related injuries can be severe and may cause a decline in the quality of life of an older person. Around 37%–56% of all falls lead to minor injuries, while 10%–15% of falls cause major injuries. Injuries that result from falls include soft tissue damage and fractures of the radius, humerus, and femoral neck. Falls are the leading cause of injury-related hospitalizations in people aged 65 years and over and account for 14% of emergency admissions and 4% of all hospital admissions in this age group . Falls that do not result in physical injuries can also have serious implications such as substantial fear of falling, which can lead to a vicious circle of frailty through the avoidance of daily activities . Furthermore, falls can contribute to the placement of older people into institutional care. In fact, falls are associated with a threefold increase in the risk of being admitted to a RACF after adjusting for other risk factors .

In economic terms the direct and indirect costs associated with falls are large and will grow as the proportion of older people increases. Direct costs include costs associated with hospital and nursing home care, professional services, rehabilitation, community-based services, use of medical equipment, medications, home modifications, and insurance administration . Apart from these costs, indirect costs from the long-term consequences of these injuries can even exceed the direct costs.

About half of falls suffered by older people occur within the home and immediate home surroundings. These occur while older people are undertaking their usual daily activities during periods of maximum activity in the morning and afternoon . This suggests that the occurrence of falls is strongly related to exposure to fall risk situations . However, falls have been shown to be not random events and large epidemiological studies have identified many risk factors for falling in older people .

68.2

Risk factors for falls

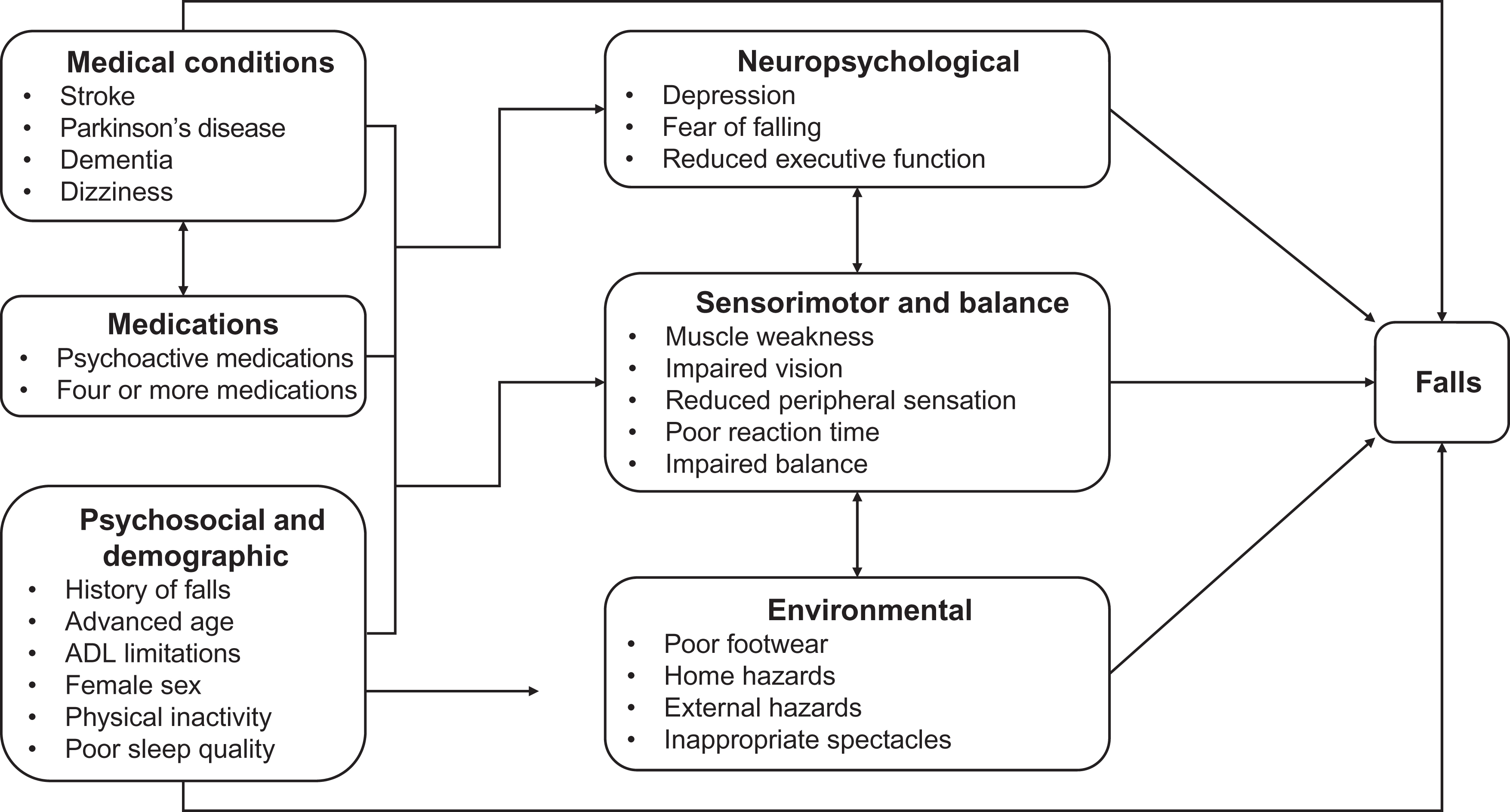

The maintenance of postural stability (i.e., the avoidance of a fall) is a complex ability that relies on the interaction of many systems, which are adversely affected by ageing and disease-related impairments . Many sociodemographic, medical, neuropsychological, and sensorimotor factors have been shown to have strong associations with falls . As a result of age-related changes, disease or adverse medication effects, sensorimotor and balance systems may become impaired and predispose to falls in the presence of extrinsic factors (such as environmental hazards) ( Fig. 68.1 ). A number of large-scale prospective cohort studies and smaller case–control studies have sought to identify these risk factors. A systematic review identified over 400 variables that have been investigated as potential fall risk factors. The risk of falls and the probability of suffering consequences that threaten independent living increase with the number of risk factors . In Table 68.1 , we have summarized the findings of many of these studies and have rated each risk factor according to the strength of the published evidence.

| Domain | Risk factor | Association |

|---|---|---|

| Psychosocial and demographic factors | Advanced age | *** |

| Female gender | ** | |

| Living alone | ** | |

| History of falls | *** | |

| Inactivity | ** | |

| Activities of daily living limitations | *** | |

| Alcohol consumption | – | |

| Sleep disturbances | ** | |

| Fear of falling | *** | |

| Medical factors | Dementia and impaired cognition | *** |

| Stroke | *** | |

| Parkinson disease | *** | |

| Abnormal neurological signs | ** | |

| Depression | *** | |

| Incontinence | ** | |

| Acute illness | ** | |

| Vestibular disorders | – | |

| Arthritis | ** | |

| Foot problems | ** | |

| Dizziness | ** | |

| Orthostatic hypotension | * | |

| Medication factors | Psychoactive medication use | *** |

| Antihypertensive use | * | |

| Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs | – | |

| Use of 4+ medications | *** | |

| Balance and mobility factors | Impaired stability when standing | ** |

| Impaired stability when leaning and reaching | *** | |

| Inadequate responses to external perturbations | * | |

| Slow voluntary stepping | ** | |

| Impaired gait and mobility | *** | |

| Impaired ability in standing up | *** | |

| Impaired ability with transfers | *** | |

| Sensory and neuromuscular factors | Visual acuity | ** |

| Visual contrast sensitivity | *** | |

| Visual field loss | ** | |

| Reduced peripheral sensation | ** | |

| Reduced vestibular function | * | |

| Muscle weakness | *** | |

| Poor reaction time | *** | |

| Environmental factors | Poor footwear | * |

| Inappropriate spectacles | * | |

| Home hazards | – | |

| External hazards | – |

68.2.1

Psychosocial and demographic risk factors

Falls are strongly associated with advanced age. Falls have also been more commonly reported in women. The difference in fall rate between men and women has been attributed to reduced muscle strength and more frequent use of psychotropic medications . In addition, older women are also more likely to sustain fall-related fractures as a result of a higher prevalence of osteoporosis. However, in hospitals and institutions, where the inpatient populations are subject to substantial selection biases (based on ill health, frailty, immobility, etc.), the reported incidence of falling is similar for men and women, or even higher for men. The finding that living alone is a risk factor for falls is most likely confounded by gender and by age, in that older women comprise most of this group.

Physical activity can improve strength, balance, and functional abilities in older people and can prevent falls . However, being more physically active does not always prevent falls . This is probably because the more physically active older person takes part in activities that increase exposure to falls risk situations. Clearly, this risk should be balanced against the benefits of increased physical functioning and independence that exercise brings.

The most surprising finding regarding associations between sociodemographic factors and falls is that alcohol consumption has not been shown to be a falls risk factor. Despite examining the issue, no significant associations have been found between alcohol use and falls in several large cohort studies . It may also be the case that the lack of a positive association between alcohol use and falls is due to response and selection biases, in that heavy alcohol consumers may underreport their drinking levels or simply decline participation in research studies.

Short and long sleep duration and poor sleep quality have been found to be independently associated with increased odds of falls in both community and residential aged care settings . Finally, fear of falling is prevalent in older people and can also lead to persistent and dysfunctional disruptions of attention and behavior. Excessive fear of falling may have a detrimental effect upon several domains of life, including restricting activities of daily living and enjoyable pastimes, which may in turn lead to physical inactivity and social isolation .

68.2.2

Medical factors

Many preexisting diseases and associated impairments have been identified as risk factors of falling, mainly through impairing postural stability. Some examples of important conditions include stroke, Parkinson disease, cognitive impairment, depression, dizziness, postural hypotension, urinary incontinence, arthritis, etc. . These conditions have been shown to be risk factors for falls in both community and institutional settings, although the importance of some of these such as incontinence and impaired cognition (with associated antipsychotic drug use) are particularly important in institutions. Vitamin D insufficiency is associated with a range of physiological and neuropsychological factors that predispose older people to fall. Increased risk of falls as a result of vitamin D deficiency has been found especially for those living in residential aged care settings , older men , and older people at greater risk of hip fracture . On the other hand, certain conditions commonly thought to be strong risk factors for falls, such as vestibular disorders and orthostatic hypotension, have not been found to be strong risk factors in community-based research studies but may be important in clinical populations.

68.2.3

Medications

Both community and institutional studies have demonstrated a relationship between medication use and falls in older people, especially the use of multiple medications (usually four or more). Use of psychoactive medications (benzodiazepines, antidepressants, and antipsychotics) has been especially associated with falls. Many epidemiological studies have examined the association between the use of any psychoactive medication and falls and fall-related injuries in older people. These studies indicate that the use of psychoactive medications leads to a two- to threefold increased risk of falling and a twofold increased risk of experiencing a hip fracture . Use of antiinflammatory drugs, however, does not appear to be associated with increased risk of falls after controlling for the presence of arthritis. The results of studies into the use of antihypertensive medications have been inconsistent and a metaanalysis concluded that there was not sufficient evidence to consider the use of these drugs to be a risk factor of falls .

68.2.4

Balance, mobility, and gait factors

Mobility—such as the ability to rise from a chair, turn while walking, and ascend and descend stairs—inherently relies on balance . Normal aging is associated with impairments in sensorimotor systems that contribute to balance, which is likely to result in an impaired ability to maintain balance when performing a range of functional tasks. Gait changes are also common with increasing age. Older people tend to walk with slower velocity, shorter step lengths, wider step widths, and a relatively increased proportion of time spent in the double-support phase . It is not clear whether these changes are due to physical limitations or an adaptive strategy for improved safety ; however, these spatiotemporal gait patterns are more common in fallers compared to nonfallers . Generally speaking, the more challenging a task is to the postural control system, the greater the effect of age and the stronger the relationship to falls. Older people, particularly those with a history of falls, are also less successful in negotiating obstacles and recovering from a trip than younger adults . Deconditioning also plays an important role in the age-related deterioration in physical function.

68.2.5

Sensory and neuromuscular factors

Good balance requires the complex integration of sensory information regarding the position of the body relative to the surroundings and the ability to generate appropriate motor responses to control body movement . Reduced balance and mobility in older people can result from impairments in sensory, motor, and central processing systems . Impairments may be the result of a specific pathology affecting a particular component of these systems, or the general progressive loss of function due to normal aging. Balance calls upon contributions from vision, proprioception, vestibular sense, muscle strength, and reaction time. Sensory systems provide information about the nature of a balance perturbation under challenging conditions. Visual input provides the brain with a continually updated reference frame regarding the position and motion of body segments in relation to each other and the environment. Impaired vision—presence of visual conditions such as cataracts and glaucoma or impaired contrast sensitivity and depth perception—is a risk factor for falls and fractures as it increases the likelihood of misjudging obstacles in the environment. Sensory input from the lower limbs provides the central nervous system with important information regarding position and movement. Even in people with no known neuropathic disease such as diabetes, impaired peripheral sensation has been associated with an increased fall risk. Vestibular input provides information about the position and motion of the head in space and is known to be closely related to balance. Adequate central processing and reaction time is necessary for voluntarily correcting a balance perturbation. Slow reaction time has been shown consistently to be an important predictor of falls. Lower limb strength decreases substantially with age which has important ramifications for balance and falls in older people. In large community-based studies, reduced quadriceps strength has been shown to increase falls risk. Similarly in RACFs, quadriceps, and ankle dorsiflexor weakness have been found to be major risk factors of falling.

68.2.6

Neuropsychological and neurobiological factors

Walking is not a fully automated process, and there is an increase in the cognitive resources required for balance and gait with increasing age. Older people with attentional limitations, to the extent that even simple tasks such as answering a question interfere with standing or walking, are at an increased risk of falls . Impaired white matter connectivity, specifically due to damaged myelin or axonal loss in the prefrontal cortex, is thought to impair the integration, manipulation, and evaluation of sensory and cognitive information , with a threshold effect in relation to falls . Functional near-infrared spectroscopy can investigate cortical brain activation while walking. One study found that higher levels of prefrontal cortical activation during walking while reciting alternate letters of the alphabet predicted falls in healthy older people .

68.2.7

Environmental factors

It has been estimated that extrinsic factors are involved in 35%–45% of falls that result in injuries, but prospective studies have not been able to demonstrate that hazards in the home are major risk factors for falls. However, the interaction between an older person’s abilities and their exposure to environmental factors is clearly important . People with high physical abilities can withstand a range of environmental challenges without falling, yet when faced with an extreme challenge, such as an icy footpath, may still fall. People with lower physical abilities can generally cope well in an environment that offers few challenges, such as in their own home, but in people with very poor abilities, falls may occur regardless of the safety of the environment. In addition, the extent of a person’s risk-taking behavior or exposure to fall risk situations also plays an important role in the interaction between older people’s abilities and their environment. There is some evidence that environmental hazards play greater roles in falls that occur away from the home where about one-quarter to one-half of falls occur. Falls occurring away from the home often involve stairs or slipping and tripping hazards, or temporary hazards that cannot be anticipated. In addition, environmental factors can play a role in whether a fall will lead to a serious injury . For example, a fall on stairs has been found to be associated with a twofold increase in risk of injury.

68.3

Fall risk screening and assessment

A range of valid tools for screening and assessing fall risk have been developed for use in older people in community, hospital, and nursing and residential care settings. Some examples with demonstrated reliability and predictive validity in prospective studies and acceptable accuracy in identifying older people who are likely to fall are discussed next.

68.3.1

Screening

Fall-risk screening provides an efficient means of identifying those people at the greatest risk of falling who should have a comprehensive fall-risk assessment performed. Fall-risk screening usually involves only reviewing up to five brief items. A simple, easy-to-administer screen is to ask older people about their history of falls in the past 12 months and assess their balance and mobility status . A number of studies have identified previous falls as one of the strongest predictors for falling again in the following year. It has therefore been suggested that health care practitioners should ask all older people about any falls they have experienced. Generally speaking, more challenging balance assessments are better able to identify older people at risk of falls compared with simple standing assessments. For example, while impaired stability during unperturbed standing is a moderate risk factor, measures of leaning balance have been consistently reported as strong risk factors in well-designed studies. Several balance assessment tools have been developed, with different predictive properties in different settings ( Table 68.2 ). Those people with a history of one or more falls in the last year and who perform poorly on a simple test of gait or balance should be assessed further.

| Setting | Screening tool |

|---|---|

| Community | The TUG measures the time taken for a person to rise from a chair, walk 3 m at normal pace with their usual assistive device, turn, return to the chair, and sit down. The TUG has shown some predictive value in prospective and retrospective studies and a time of 12 or more seconds to complete the tests indicates impaired functioning in community living older people |

| Emergency department | Used in people presenting to the emergency department after a fall. Three simple questions (fall in the past 12 months, fall indoors, unable to get up after a fall) identify people at increased risk of falls |

| Hospital—subacute |

|

| Hospital—acute |

|

| Residential aged care facilities | A clinical algorithm based on a resident’s cognitive status, impulsivity, standing balance, need for a walking frame, past falls and use of antidepressants, and hypnotics/anxiolytics can identify residents at increased risk of falls over 6 months |

68.3.2

Assessment

In order to develop an individualized care plan for preventing falls, the factors contributing to a person’s increased risk of falling need to be systematically identified. Assessment tools provide detailed information on the underlying deficits contributing to risk and should be used to guide interventions. When trying to establish the cause of a fall, it is important to remember that most falls occur as a result of an interaction between intrinsic and extrinsic factors and that multiple factors increase the risk of falls. Assessing fall risk typically involves either the use of multifactorial assessment tools that cover a wide range of fall risk factors, or individual functional mobility assessments that focus on the physiological and functional domains of postural stability, including vision, strength, coordination, balance, and gait. A range of comprehensive multifactorial assessment tools have been developed for use in a range of settings and some examples are summarized in Table 68.3 . The risk factors as presented in Table 68.4 have been identified as being more prevalent in fallers than in nonfallers and should be assessed and managed if present. Some examples of the clinical assessments are outlined in Table 68.4 . The choice of tool depends on the time and equipment available and the level of ability of the older people being assessed.

| Setting | Assessment tool |

|---|---|

| Community |

|

| Hospital—subacute | The Peninsula health FRAT has three sections: (1) falls risk status, (2) risk factor checklist, and (3) action plan |

| Hospital—acute | The “care plan assessment items” incorporates 12 items into the daily care plan, including intrinsic risk factors (medications, vision, blood pressure, mobility, etc.) and environmental risk factors (safe environment, appropriate bed height, nurse call bell accessible, etc.) |

| Residential aged care facilities | Relatively few general FRATs have been developed for use in RACFs, but the FRAT can also be used here |

| Risk factor | Assessment tool |

|---|---|

| Balance and gait |

|

| Cognitive impairment |

|

| Feet and footwear | An assessment of footwear and foot problems involves assessing foot pain and other foot problems as well as using a safe shoe checklist |

| Syncope/dizziness | It is important to ensure that older people reporting presyncope or syncope undergo appropriate assessment and intervention, particularly if the cause is not obvious. This may include an electrocardiogram, echocardiography, Holter monitoring, tilt-table testing and carotid sinus massage or insertion of an implantable loop recorder. Peripheral vestibular function can be assessed using the Halmagyi head-thrust test. BPPV is usually diagnosed using the Dix–Hallpike test in general practice |

| Medications | A medication review should focus on appropriate prescribing (i.e., ensuring that medications are used safely and effectively) |

| Vision | Vision screening should include asking older people about their vision and checking for signs of visual deterioration. Visual acuity or contrast sensitivity can be assessed using a standard letter chart or the Melbourne Edge test, respectively |

| Environment | A number of home hazard checklists have been developed and are often culturally dependent. Some examples are the home environment Survey, the Westmead home safety assessment , the Home Falls and Accidents Screening Tool (HomeFast) ( http://www.health.vic.gov.au/agedcare/maintaining/falls/providers/home/env_check.htm ), and the Home-Screen Tool. A good home hazard checklist contains a range of environmental risk factors including footwear and behavioral factors related to how the older person interacts with their environment |

| Fear of falling |

|

68.3.3

Remote assessments

Wearable sensors typically contain a triaxial accelerometer, gyroscope, and pressure sensor and can be attached to the waist, wrist or ankle, or on a pendant. Several studies have demonstrated that it is feasible to monitor daily activities in older people and that a week’s monitoring is sufficient to assess mobility patterns . To date, about 20 studies have derived models for fall prediction, often with good accuracy, specificity, and sensitivity . The amount of gait (number of steps), and gait quality (variability, complexity, and smoothness) can differentiate fallers from nonfallers . However, it should be noted that the derived models might be overoptimistic and are unlikely to maintain their reported performance during everyday use or provide useful prognostic tools .

68.4

Fall prevention strategies

There is now a strong evidence to support interventions for the prevention of falls in older people. In general, research studies have followed two major approaches. The first approach involves single interventions that address one risk factor considered amenable to intervention. Single intervention strategies shown to reduce falls successfully in randomized controlled trials (RCTs) include exercise, enhanced podiatry, occupational therapy interventions, psychotropic medication withdrawal, cognitive–behavioral therapy, expedited cataract extraction, provision of single lens glasses for people wearing multifocal glasses, and cardiac pacing for carotid sinus hypersensitivity. The second approach involves interventions of a multifactorial nature, which target risk factors identified in fall risk assessment. A selection of successful trials is described next and presented in Table 68.5 for community settings and in Table 68.6 for institutional settings. For a full overview, please refer to systematic reviews from the Cochrane Collaboration .

| Population and numbers | Single (S) or multifactorial (M) | Interventions and duration of follow-up (I=intervention, C=control) | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exercise | |||

| S |

| |

| S |

| |

| S |

| |

| S |

| |

| S |

| |

| Feet and footwear | |||

| M |

| |

| Medical and medications | |||

| S |

| |

| S |

| |

| S |

| |

| Vision | |||

|

| ||

|

| ||

| Environment | |||

| M |

| |

| S |

| |

| M |

| |

| M |

| |

| Fear of falling | |||

| S |

| |

| Tailored multifactorial based on assessment | |||

| M |

| |

| M |

| |

| M |

| |

| M |

| |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree