Summary of Key Points

- •

With the realization that many more lung cancers are being detected, which may not only be indolent but also smaller than 2 cm, thoracic surgeons are considering sublobar resections in their practice.

- •

There are conflicting data from meta-analyses and large databases regarding the efficacy of segmentectomy or wedge resection compared with lobectomy.

- •

Despite promising data from propensity-matched trials of lobectomy compared with sublobar resection, the results of the Japanese and American randomized trials for management of the less than 2-cm nodule should define the proper resection for this population.

Present-day surgery for lung cancer with curative intent consists of resecting (removing) the proper extent of the lung parenchyma bearing the cancer lesion, along with the local–regional lymph nodes, which may contain cancer metastasis. For resecting the lung parenchyma, the following surgical procedures may be performed, depending on the extent of the disease: pneumonectomy (removal of the entire lung on either side), bilobectomy (removal of two adjacent lobes), lobectomy (removal of a single lobe), segmentectomy (segmental resection, removal of a single segment or adjacent segments), and wedge or partial resection (removal of wedge-shaped parenchyma regardless of the bronchovascular anatomy). When the proximal portion of the bronchus is involved by the direct extension of the tumor or by lymph node metastasis at the hilum and the resected end of the bronchus with lobectomy or pneumonectomy cannot be tumor-free, a sleeve resection, which entails resection of the proximal portion of the bronchus and reconstruction, might be considered in conjunction with lobectomy (sleeve lobectomy) or pneumonectomy (sleeve pneumonectomy) to ensure a safe surgical margin. Sleeve resection enables tumor-free resection without sacrificing the noninvolved lung parenchyma.

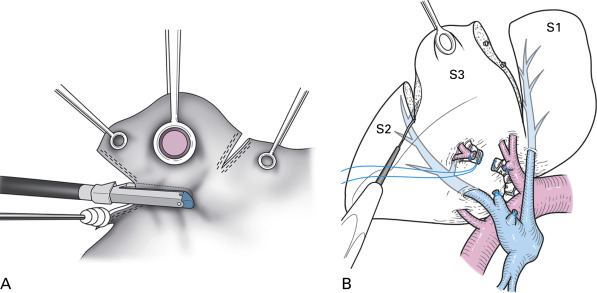

With respect to the pulmonary hilum, these procedures can be divided into anatomic resection (pneumonectomy, bilobectomy, lobectomy, and segmentectomy) and nonanatomic resection (wedge resection). In anatomic resection, the extent of the pulmonary parenchyma for resection is determined by the extent of perfusion of the pulmonary vessels as well as by the extent of aeration of the bronchi, which are divided at the hilum. In nonanatomic resection, the extent of the parenchymal resection is determined solely by the location of the target lesion. Although segmentectomy and wedge resection are both referred to as sublobar resection, the technical characteristics of these two procedures are quite different ( Fig. 29.1 ).

In this chapter, we discuss the proper selection of the mode of parenchymal lung resection, with particular focus on stage I and II lung cancer, from both oncologic and technical viewpoints. We also present an overview of the evolution of lung cancer surgery since the 1930s, when the only option available for surgical resection for lung cancer was pneumonectomy.

Overview of the Evolution of Lung Cancer Surgery

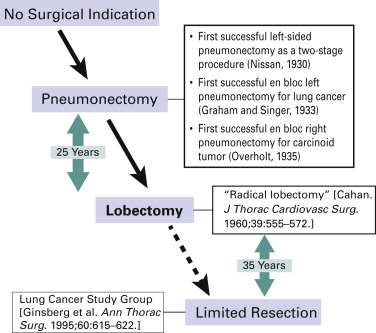

Historically, lung cancer surgery has evolved so as to minimize the extent of parenchymal resection ( Fig. 29.2 ). Surgeons have been trying to achieve an optimal balance between radical surgery and surgery that preserves postoperative lung function. Kummel presented the earliest report, published in 1911, of a pneumonectomy of the right side; the patient was a 40-year-old man who died on the sixth postoperative day. After a series of early postoperative deaths after pneumonectomy in the 1920s, Evarts Graham Churchill in St. Louis, Missouri, reported the first successful pneumonectomy, using a tourniquet technique, on a 48-year-old male doctor with lung cancer in 1932. After this landmark operation, reports of successful pneumonectomies for lung cancer were presented by Rienhoff and Broyles, Alexander, Archibald, Sauerbruch, and Overholt. In 1940, Overholt reviewed 110 pneumonectomies, including his own 15 cases, for benign and malignant lung diseases and found a mortality rate of 65% for procedures performed for malignant disease. He noted that the operability of primary lung cancer was 25%. In the 1940s, pneumonectomy was established as the standard mode of pulmonary resection for lung cancer. Allison performed pneumonectomy with intrapericardial ligation of the pulmonary vessels, and more importantly, adding local–regional lymph node dissection to pneumonectomy was proposed as radical surgery for lung cancer. Cahan and coworkers called this procedure radical pneumonectomy, which indicated the combination of parenchymal resection and lymph node dissection.

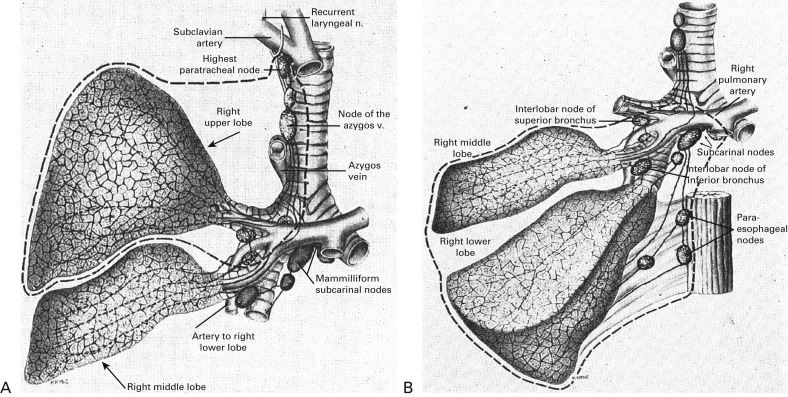

In the 1950s and 1960s, lobectomy gradually replaced pneumonectomy. In 1950, Churchill et al. reported that the 5-year survival rate with lobectomy (19%) was better than that with pneumonectomy (12%). Belcher reported a 5-year survival rate after lobectomy of 61%, which was outstanding at that time. In 1960, Cahan again defined radical lobectomy as an operation in which one or two lobes of an entire lung are excised in a block dissection, along with certain regional hilar and mediastinal lymphatics ( Fig. 29.3 ). The extent of lymph node dissection was also defined according to the primary site of the lung cancer. Cahan analyzed the outcomes of 48 radical lobectomies for primary and metastatic lung cancers and concluded that survival for 5 or more years could be attributed in large part to radical lobectomy associated with more extensive lymphatic dissection. In the 1970s and 1980s, lobectomy was considered the standard mode of resection for primary lung cancer and pneumonectomy was no longer the standard approach.

Although lobectomy came to be considered the standard of care for primary lung cancer, lesser resections—segmentectomy and wedge resection—for peripheral lung cancer have always been reserved for patients who are not able to tolerate more extensive procedures such as lobectomy or pneumonectomy. Churchill and Belsey originally introduced segmental resection in 1939 as segmental pneumonectomy for the treatment of benign lung diseases. This technique was later advocated for use in patients who had operable lung cancer and limited pulmonary reserve. In 1972, Le Roux reported on 17 patients with peripheral tumors who had undergone segmental resection. In 1973, Jensik et al. suggested that anatomic pulmonary segmentectomy could be effectively applied to small primary lung cancers when the surgical margins were sufficient.

The results of some subsequent nonrandomized studies showed that excellent outcomes could be achieved with segmental resection for patients with early cancers. These reports stimulated a debate about the optimal resection technique for early-stage nonsmall cell lung cancer (NSCLC), which the Lung Cancer Study Group addressed in a prospective, randomized trial conducted with 247 patients with stage IA NSCLC. The investigators examined postoperative prognosis and pulmonary function after limited pulmonary resection, including anatomic segmentectomy and nonanatomic wide wedge resection, or lobectomy. They found a 75% increase in the recurrence rate ( p = 0.02) and a 30% increase in the overall death rate ( p = 0.08) for limited resection. With regard to pulmonary function, the investigators judged the follow-up and reporting to be somewhat unreliable because study funding was terminated early. The authors concluded that limited resection did not confer improved perioperative morbidity, mortality, or late postoperative pulmonary function. Because of the higher rates of death and local–regional recurrence associated with limited resection, lobectomy still must be considered the surgical procedure of choice for patients with peripheral T1 N0 NSCLC. Because this landmark trial is the only randomized trial in which limited resection was directly compared with lobectomy, the results are still considered valid.

In 2006 and 2011, Allen et al. and Darling et al. published results from a prospective, randomized trial—the American College of Surgery Oncology Group Z0030 study—designed to evaluate the prognostic significance of lymph node dissection in lung cancer. In this trial, systematic sampling was compared with lymph node dissection for N0 or nonhilar N1, T1, or T2 NSCLC (stage I and II). In short, the results of this study did not support a prognostic advantage of lymph node dissection over sampling. The authors concluded that if systematic and thorough presection sampling of the mediastinal and hilar lymph nodes is negative, mediastinal lymph node dissection does not improve survival for patients with early-stage NSCLC; the authors added that these results cannot be generalized to patients who have radiographic staging or higher-stage tumors.

On the basis of the results of these two important prospective studies, it is widely accepted that the present-day standard of care should be at least lobectomy with lymph node sampling or dissection for stage I and II lung cancer.

Results of Surgical Resection for Stage I and Ii Lung Cancer

The outcome of surgery for stage I and II lung cancer has been best demonstrated in publications in 2006 and 2007 by the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer (IASLC), with results based on the largest and latest global database. In 1998, for the preparation of the forthcoming seventh edition of the TNM Classification of Malignant Tumours (published in 2009), the IASLC established its Lung Cancer Staging Project. Data were contributed from 46 sources in more than 19 countries. Adequate data were available for 67,725 cases of NSCLC and 8088 cases of small cell lung cancer (SCLC) treated with all modalities of care between 1990 and 2000. In these studies, the survival rates for clinical (c) and pathologic (p) stage I and II NSCLC were given according to the seventh edition of the tumor, node, and metastasis (TNM) system. The 5-year survival rates were 50% for cIA, 43% for cIB, 36% for cIIA, and 25% for cIIB lung cancer. The corresponding 5-year survival rates for pathologic stage lung cancer were 73% for pIA, 58% for pIB, 48% for pIIA, and 36% for pIIB. Current consensus is that postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy improves survival for patients with lung cancer of stage II or higher, as indicated by the results of a series of large-scale clinical trials in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Although the IASLC database contained 349 cases of resected SCLC with pathologic TNM staging available, the survival data were given only for clinical stages. With regard to c-stage I and II, the 5-year survival rates were 38% for cIA, 21% for cIB, 38% for cIIA (only 8 patients), and 18% for cIIB.

Detailed survival data for patients with resected lung cancer were reported in a series of Japanese lung cancer registry studies. A retrospective registry study has been performed three times for patients who had resections in 1994, 1999, and 2004. The latest report was based on 11,663 patients with all histologic types who had resections in 2004 and for whom survival data were provided according to tumor classification with use of the seventh edition of the TNM classification. Among these 11,663 patients, 243 (2.1%) had tumors with small cell histology. The 5-year survival rates for c-stage lung cancer were 82% for cIA, 66.1% for cIB, 54.5% for cIIA, and 46.4% for cIIB. The 5-year survival rates for p-stage lung cancer were 86.8% for pIA, 73.9% for pIB, 61.6% for pIIA, and 49.8% for pIIB.

A new classification of adenocarcinoma of the lung, which included earlier forms of adenocarcinoma, was published in 2011 to provide uniform terminology and diagnostic criteria. In short, new concepts were introduced, such as adenocarcinoma in situ (AIS) and minimally invasive adenocarcinoma (MIA), for small solitary adenocarcinomas with either pure lepidic growth or predominant lepidic growth smaller than 5 mm to define patients who, if they were to undergo complete resection, would be expected to have 100% or near-100% disease-specific survival, respectively. By contrast, adenocarcinomas are also classified according to their predominant pattern, with comprehensive histologic subtyping as lepidic, acinar, papillary, or solid. Earlier forms such as AIS and MIA were recognized only after the advent of high-resolution computed tomography and the dissemination of computed tomography screening programs. In the Japanese Registry Study, these early-stage lung cancers had been included with stage IA cancers, and the proportion of these cancers may be associated with a difference in survival, especially for stage IA disease. The surgical significance of these classifications has also been analyzed. In studies published in 2011 and 2013, the prognosis of 545 radiographically determined noninvasive adenocarcinomas of the lung that showed ground-glass opacity (GGO) was described; a consolidation-to-tumor ratio of 0.25 or less in cT1a was used as a radiographic criterion of noninvasive cancer, and the lesion was resected using lobectomy. The 5-year survival rates for noninvasive and invasive adenocarcinomas were 96.7% and 88.9%, respectively. This surgical outcome indicates the realistic possibility of lesser resections, such as segmentectomy and wedge resection, for early lung cancers.

Possibility of Sublobar, Limited Resection for Stage I and II Lung Cancer

Technical and Pathologic Considerations

When we think of sublobar resection, especially segmental resection, as a possible radical resection for lung cancer, in which no tumor tissue must be left behind, we must consider several factors. In sublobar resection, the lung parenchyma must be transected and divided for the procedure to be complete, whereas in lobectomy, the fissure is divided to remove the entire lobe. Sublobar resection has some technical limitations associated with tumor size, location, histologic type, and node involvement. In particular, tumor size and location are closely related to the safe surgical margin in a radical resection.

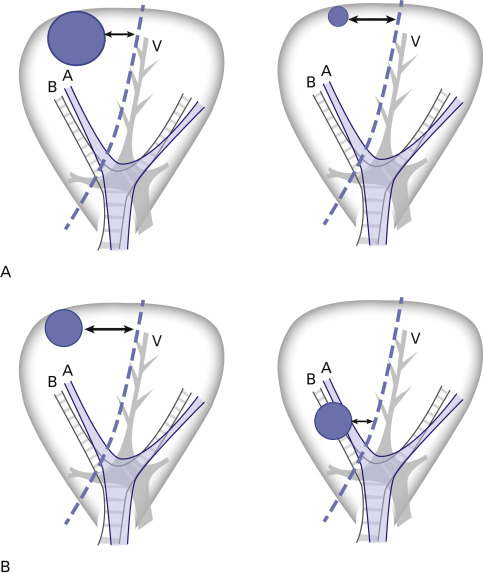

Tumor size and local recurrence after sublobar resection have been studied extensively. Bando et al. studied 74 patients who had sublobar resections and found that the local–regional recurrence rate was 2% for tumors less than 2 cm and 33% for tumors larger than 2 cm. Fernando et al. and Okada et al. also found that tumor size less than 2 cm was an independent, favorable predictor of a smaller chance of recurrence and better survival after sublobar resection. If we consider the distance between the tumor and the surgical margin of the lung parenchyma, it is easy to understand why larger tumors have a greater chance of local recurrence ( Fig. 29.4A ). Another important factor is the location of the tumor in relation to the pleural surface and the hilum. A fundamental, geometric understanding of a lung segment is that the segment is fan-shaped, with the base on the pleural surface and the apex at the pulmonary hilum. Therefore, the distance between the tumor and the resection line is inevitably smaller for a tumor that is close to the hilum, even if the tumor is small ( Fig. 29.4B ). In general, even for a tumor diameter of 2 cm or less, segmentectomy or wedge resection should be performed only if the tumor is located in the outer third of the lung parenchyma. Other unfavorable factors for limited resection are an aggressive histology, such as SCLC, and lymph node involvement. These conditions indicate a higher likelihood of tumor spread in the lobe that contains the segment.

Oncologic Considerations

Limited, sublobar resection should be considered for lung cancer in the following three situations:

- •

T1 N0 M0 lung cancer in individuals with limited cardiopulmonary reserve, regardless of the type of lesion;

- •

early lung cancer with a predominantly GGO appearance (pathologic AIS or MIA);

- •

small but invasive lung cancers located in the periphery of the lung.

As noted earlier, considerable interest in sublobar resection arose in the 1970s and 1980s when the feasibility of limited resection for patients with a compromised cardiopulmonary reserve was demonstrated. At that time, the 5-year survival and recurrence rates for sublobar resection were considered inferior to the rates for lobectomy, and sublobar resection was restricted to patients with impaired cardiac function or substantial comorbidities that precluded conventional lobectomy. In fact, in 1994, Warren and Faber demonstrated decreased survival and increased recurrence among 173 patients with stage I NSCLC who had sublobar resection or lobectomy. However, the results of single-institution retrospective investigations published between 1997 and 2004, in which the equivalency of sublobar resection to lobectomy for patients with limited cardiopulmonary reserve was evaluated, contradict earlier results and demonstrate that stage I disease portends a survival advantage regardless of the extent of surgical resection or the histologic subtype. Campione et al. found no significant difference in survival between lobectomy and anatomic segmentectomy in a series of 121 patients with stage IA lung cancer. Other studies demonstrated similar results for segmentectomy and lobectomy. The surgical indication of limited resection for patients with stage IA lung cancer with limited cardiopulmonary reserve is the reasonable treatment of choice.

As discussed previously, AIS (formerly bronchioloalveolar carcinoma) and MIA are novel concepts that indicate the noninvasive or minimally invasive nature of adenocarcinoma with the unique radiographic presentation of GGO. In a variety of retrospective Japanese studies, the use of limited resection for patients with nonsolid (pure) or part-solid (mixed) GGO tumors has been assessed. In each of these studies, patients with an AIS or an MIA had prolonged survival and lower recurrence after resection compared with patients with other subtypes of NSCLC. The use of sublobar resection for these early tumors was based on a clinical–pathologic study of the correlation between the degree of invasive growth (stromal invasion) and the prognosis. Sakurai et al. classified 380 resected adenocarcinomas of 2 cm or less in diameter according to the degree of invasive growth (structural deformity and its location in the adenocarcinoma) and showed that 100% survival could be achieved for patients with AIS or MIA, despite the mode of pulmonary resection. On the basis of these clinical–pathologic observations, it would be reasonable to consider sublobar resection for AIS and MIA with GGO according to the location and size of the tumor.

The indication for sublobar resection must be considered from not only an oncologic but also an anatomic perspective. In the case of a tumor that is located deep inside the lung parenchyma, sublobar resection cannot ensure a safe surgical margin because the surgical margin is close to the hilar structures. As noted previously, the shortest distance between a tumor and the resected margin falls in the area close to the hilum. The tumor diameter also affects the distance to the surgical margin. Therefore as with segmentectomy or wedge resection, sublobar resection should be used only when the tumor is located in the outer third of the lung parenchyma and, preferably, is 2 cm or less in diameter. For tumors that are located in the inner two-thirds of the lung parenchyma or that are larger than 2 cm in diameter, lobectomy should still be selected, regardless of the tumor pathology.

However, for a histologically invasive lung cancer that is a small (≤2 cm, T1a), solitary nodule located in the periphery of the lung, the feasibility of limited, sublobar resection must be assessed from the perspective of the present day. Such an assessment would entail revision of the Lung Cancer Study Group study performed in the late 1980s. Indeed, the present-day routine workup for patients with resectable lung cancer is different from the workup done in the 1980s. To investigate sublobar resection for early lung cancer, a few prospective studies are ongoing. As summarized by Iwata, the role of sublobar resection has been explored in large databases such as Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program and the National Cancer Database (NCDB). Veluswamy et al.’s analysis of 2008 adenocarcinomas and 1139 squamous cell carcinomas all less than 2 cm in patients older than 65 revealed that wedge was always inferior to other resections independent of histology; however, for adenocarcinoma, overall survival and lung cancer–specific survival of segmentectomy were equivalent to lobectomy, but not for squamous cell carcinoma. By contrast, Khullar et al.’s and Speicher’s et al.’s analyses of clinical stage I patients in the NCDB revealed that overall survival was inferior for sublobar resections compared with lobectomy. These analyses, however, were limited in that only 290 of 987 propensity-matched patients in the NCDB could be analyzed for survival because survival was not available past 2006. Meta-analyses investigating the role of sublobar resections also failed to have consensus. In Cao et al.’s analysis of 54 studies, intentional use of sublobar resections resulted in similar overall survival to lobes while this was not seen in cases where a sublobar resection was performed for compromised patients. The disease-free survival always favored lobectomies. Bao et al.’s survival analysis of 22 studies found equivalent overall survival between segmentectomy and lobectomy only for tumors smaller than 2 cm. Finally, in an analysis of 4564 lobectomies and 2287 sublobar resections, Taioli et al. concluded that the high degree of heterogeneity of study design for these analyses might preclude useful conclusions using conventional meta-analyses to study these resections. Five propensity-matched studies with 69 to 312 matched sublobar and lobectomy patients with 3-year to 10-year overall survival data have been published. Common matching parameters have included age, sex, and tumor size, and all studies found no differences in disease-free survival or overall survival comparing segmentectomy with lobectomy. Kodama et al.’s study is notable in that it summarized 10-year intermediate end points from surgery revealing that freedom from local–regional recurrence for segmentectomy and lobectomy was 95.3% and 97%, respectively, and no differences in overall survival were recorded for 10-year survival (segmentectomy, 83.2%; lobectomy, 88%). With regard to the use of video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) segmentectomy, two studies have revealed equal overall survival and disease-free survival for VATS segmentectomy compared with VATS lobectomy, whereas Ghaly et al. have reported no difference in disease-free survival or overall survival for 91 VATS segmentectomies compared with 102 open chest segmentectomies.

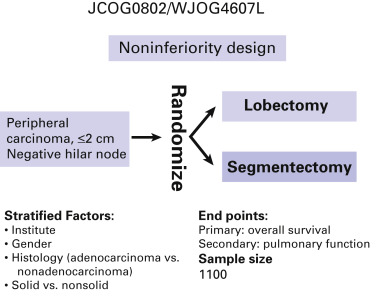

Randomized clinical trials with peripheral lung cancers no more than 2 cm in diameter as the target lesions are being conducted in the United States by the Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB 140503; ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00499330) and in Japan by the Japan Clinical Oncology Group and the West Japan Oncology Group (JCOG0802/WJOG4607L). For the CALGB trial, the primary end point is disease-free survival and the secondary end points are overall survival, rate of local–regional and systemic recurrence, and pulmonary function; the estimated enrollment is 1258. For the Japanese trial, the end points are overall survival (primary) and postoperative pulmonary function (secondary), and the targeted accrual is 1100 patients ( Fig. 29.5 ). If the prognosis for patients who have segmentectomy is not significantly inferior to that for patients who have lobectomy and if the postoperative pulmonary function is significantly better for patients who have segmentectomy, we can definitively conclude that the standard surgical modality for these early tumors should be segmentectomy.